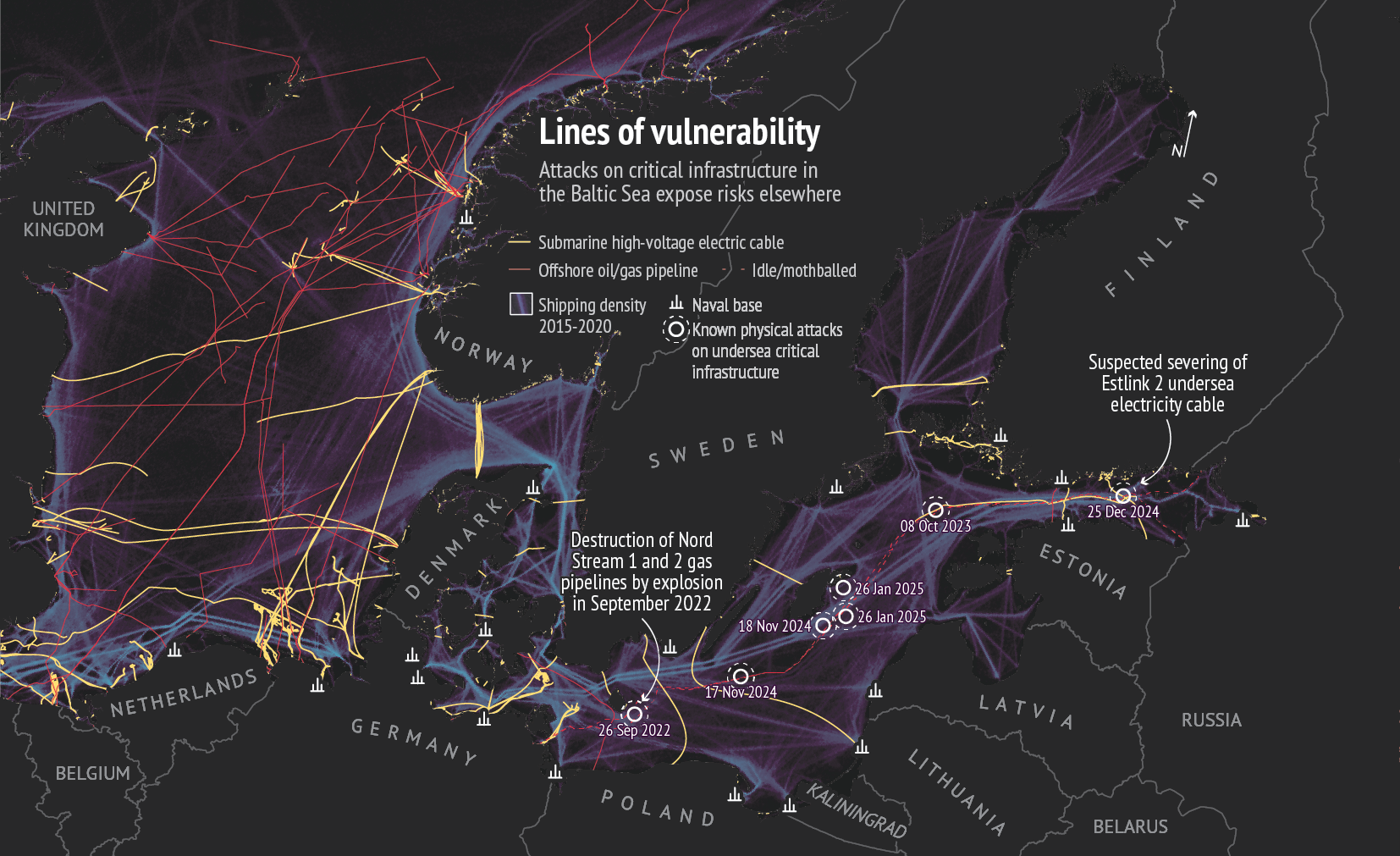

Europe’s energy infrastructure is under attack. Russia is already engaging in hybrid aggression, targeting electricity cables and gas pipelines in the Baltic Sea, and exposing deep vulnerabilities at the heart of Europe’s energy system. ‘Russia’s invasion of Ukraine clearly shows European energy infrastructure is a priority target for Russia’, affirmed Jean-Charles Ellermann-Kingombe, NATO’s Assistant Secretary General, in June 2025(1).

However, across much of Europe’s energy system, vulnerabilities persist. Critical infrastructure faces not only unresolved weaknesses but mounting geopolitical risks – particularly in the offshore transmission network. As long as this lasts, the EU will remain under constant threat from low-risk attacks causing significant societal, economic and military disruption. It is courting disaster under a sword of Damocles.

Few would dispute that critical energy infrastructure – from power plants to pipelines to cables – must be resilient. The EU’s security of supply framework acknowledges the danger of malicious attacks, while the Preparedness Union of March 2025 proposes reactive measures such as stockpiling repair equipment and enhancing cooperation with NATO to defend infrastructure. However, the vulnerabilities in the current energy system run deeper, exposing a profound weakness in how energy infrastructure is secured, managed and constructed. It needs to be resilient by design.

Data: European Commission, GISCO, 2024; Open Street Map, 2024; Global Energy Monitor, 2023; European Commission, EMODnet, 2023; World Bank, Global Shipping Traffic Density, 2021.

This Brief analyses reactive responses and proposes proactive solutions to the challenge of Russian aggression, with a focus on spatial planning and the physical security of undersea infrastructure. It calls for a holistic rethinking of how the energy system is planned, constructed and managed, advocating for the integration of security considerations from the outset(2).

Planning for peace

Current system planning and design is meant for a different era based on a short-term notion of efficiency where smaller upfront costs and less construction are encouraged. Security issues and geopolitical risks were historically overlooked. Such short-term thinking has led to many of the current vulnerabilities, giving rise to two major challenges.

The first challenge is the physical threat to energy infrastructure. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, there have been several incidents where submarine cables were severed by Russian-affiliated vessels. In December 2024, the Eagle S, a vessel belonging to Russia’s shadow fleet, was apprehended by Finnish authorities after severing EstLink 2, a critical electricity interconnector linking Finland and Estonia. The vessel had military grade detection hardware in its hull(3), pointing to a direct, premeditated and malicious attack on European energy infrastructure.

This was far from an isolated incident, and reflects a consistent strategy by the Russian Federation to undermine Europe’s energy security. In Ukraine, it has pursued similar tactics by systematically attacking energy infrastructure, including transmission lines and power stations.

The second challenge concerns the modernisation, expansion and operation of the grid. Europe’s electricity grid is, on average, 40 years old. Years of underinvestment mean that it now needs considerable upgrading. At the same time, the energy transition is altering traditional operating models and the geography of energy generation. Where once centralised fossil-fuel power stations dominated the landscape, now wind turbines in the North Sea and solar farms in southern Europe propel energy into homes. This shift requires a fundamental rethink of how and where electricity is generated, how it can be transmitted most efficiently and where it is ultimately needed.

According to the Offshore Grid Development Plan, Europe will need 54 000 kilometres of new transmission lines to connect almost 500 GW of new generation capacity(4). Additionally, the European Commission’s recommendation for anticipatory grid investments projects over €1.2 trillion in investments by 2040, building on the €584 billion envisaged by 2030(5).

While some understanding of modernisation and adaptation are filtering into the energy system, security concerns are not featuring prominently enough(6). In the case of the Netherlands, offshore wind facilities are expected to generate 75% of the country’s electricity by 2032 but are planned to be connected to the mainland by just a handful of vulnerable landing points(7). Cross-border infrastructure remains even more limited. Construction of new lines can take years, if not decades. The Baltic states, for example, currently have just four interconnections to the broader European grid, three of which run through maritime zones regularly transited by Russian ships. Europe’s islands are uniquely vulnerable with often just one or two connections to a mainland entity.

Reactive solutions

The Joint Communication to strengthen the security and resilience of submarine cables issued in February 2025 proposes mostly reactive solutions. These include armoured reinforcement of cables, burying cables beneath the seabed, better undersea surveillance of cables to enable rapid detection of damage, accelerating repair efforts to minimise disruption and defending existing infrastructure. However, these solutions tend to patch over existing vulnerabilities without solving them.

Armoured reinforcement of both new and existing cables does not eliminate the risk of attacks. More sophisticated tools can still penetrate armoured casings, while explosives such as those used to sabotage the Nord Stream pipeline remain a persistent threat. Gas infrastructure is especially vulnerable in this regard, as explosives can cause extensive damage far beyond the initial point of impact.

Burying cables can enhance protection but is technically difficult, costly and environmentally damaging. Moreover, it can complicate repair operations and often leaves portions of the cable unburied, although technology is improving rapidly in this area. This also overlooks the fact that the seabed – particularly in offshore areas – is already crisscrossed with other infrastructure, increasing the risk of accidental damage to existing cables. Meanwhile permitting and feasibility studies incur major delays when rapid infrastructure deployment is of paramount importance.

Better surveillance is essential but requires substantial resources, which may inadvertently increase the appeal of hybrid warfare. Subsea cables span considerable distances, are often located far from shore and sometimes traverse international waters, requiring sophisticated monitoring solutions. Maritime drones, while valuable, seem more suited to documenting aggression than deterring it. While surveillance alone seems to have deterred some attacks, it is unlikely to constrain a hostile actor in wartime.

Faster repairs are crucial, but they only serve to reduce the impact of damage rather than prevent it. A large-scale attack – unlike the isolated incidents seen in 2024 – would likely overwhelm capacity. Some existing cables are not possible to repair, meaning an attack would permanently cripple them. Moreover, there are hidden costs even when the system can be rapidly repaired. The repair costs of EstLink 2 were €50-60 million but that figure does not include the near doubling of electricity prices alongside system balancing costs over the six months that the cable was out of action(8).

Defending infrastructure with military assets will always be an uphill struggle. By June 2025, Russia’s shadow fleet, which has been weaponised in the past to attack critical infrastructure, comprised over 1 000 vessels. By comparison, in June 2024 the Joint Expeditionary Force, a taskforce defending critical infrastructure in the Baltic region, numbered just 28 vessels(9).

Structurally, therefore, solutions focusing on reacting, rather than limiting the effect of an attack, will not be enough to secure Europe’s critical infrastructure.

Coordinated spatial planning

Europe’s energy system has to be resilient by design. Such a system would feature higher volumes of interconnection, flexible hybrid transmission and multiple diffuse connection points. Infrastructure must also be deployed at greater speed to match the urgency of current threats, and with clearer direction to encourage the scale of investment required. The key to this system is coordinated spatial planning with security criteria integrated from the start.

Currently energy planning at the EU level – both maritime and land-based – neither provides the necessary clarity nor accounts for speed and security considerations. The Maritime Spatial Planning Directive (MSPD) focuses primarily on reducing conflict between resource exploitation, fishing, energy development, and environmental concerns. The Renewable Energy Directive (RED III) pays lip service to spatial planning by allowing for acceleration zones to speed up permitting and to encourage renewables development, but does not cover physical security. The Ten-Year Network Development Plan (TYNDP) is devised by Europe’s energy system operators in coordination with EU bodies but focuses on system needs and is constrained by national concerns. Finally, the Critical Entities Resilience Directive (CERD) includes some relevant guidance but covers 11 sectors and is largely reactive. All these directives and plans are overseen by a plethora of EU bodies. This complexity is further exacerbated at Member State level where energy remains a national competency. The result is no clear spatial planning strategy and certainly not one that factors in the dangerous geopolitical environment where energy infrastructure is a target.

Coherent spatial planning offers at least three key advantages for enhancing the security of the energy system. Firstly, a unified process enables input from various actors simultaneously, allowing for more balanced decision-making. Security concerns vary, ranging from radar placement to the routes, design and type of cables used in cross-border infrastructure. This is especially important as it allows militaries to better understand where key infrastructure is located or planned. Integrating security from the outset can also speed up projects, as demonstrated by route changes to EstLink 3, following cable sabotage. A single, coordinated process would therefore provide clarity, accelerating strategic projects and creating clearer investment pathways.

Secondly, it would help unify the currently fragmented approaches to gas, electricity and hydrogen. As the electricity blackout in Spain demonstrated, without electricity LNG terminals cannot operate. After a major storm in January 2025, some consumers in Ireland were likewise surprised to discover that their gas boilers did not work during a power cut. The energy system is interdependent, so it makes little sense to manage its components in isolation. This also applies to treating it as 27 separate national systems.

Thirdly, it enhances efficiency. Some parts of Europe are better suited to solar generation while others for wind, hydro or nuclear. From an efficiency standpoint, therefore, it makes sense to view the whole system as a spatial whole and then decide where it is best to place infrastructure and generation capacity.

The end not just the means

Coordinated spatial planning, however, would just be the means. The end goal is for European states to build much more energy infrastructure and fast. A limited number of connection points will always present easy targets for a hostile actor.

European energy security and independence will be underpinned by domestically generated power. Offshore energy generation is especially vulnerable to attacks on cables. One proposed solution, outlined in the Pathway 2.0 study by several European energy system operators, is a meshed system of lower-value undersea cables(10). These would allow individual windfarms to connect to multiple hubs and also to one another, enabling electricity to be rerouted if a single cable is severed. A crisscrossed grid in the North Sea could thus better guarantee a constant flow of energy from what amounts to a renewable energy power hub. More closely integrating continental electricity systems remains a core priority, but this can also be achieved by expanding smaller connections across multiple locations rather than relying solely on large boutique cross-border interconnections. Encouraging community electricity projects and localised storage will also increase the resilience of electricity supply by creating hundreds, if not thousands, of critical connection points.

Europe’s energy system is under attack. It is time to put it on a war footing.

References

- 1 Jean-Charles Ellermann-Kingombe, speaking at the European Sustainability Week, 10 June 2025.

- 2 This Brief does not address cybersecurity, a domain in which the threat is already well recognised with attacks happening daily in some Member States.

- 3 ‘Russia-linked cable-cutting tanker seized by Finland was “loaded with spying equipment”’, Lloyd’s List, 27 December 2024.

- 4 ENTSO-E, ‘Offshore Network Development Plans’.

- 5 European Commission, ‘EU guidance on ensuring electricity grids are fit for the future’, 2 June 2025.

- 6 Author’s discussion with system operators and the European Commission.

- 7 Bekkers, F. et al, The High Value of the North Sea, The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, 2021.

- 8 ERR, ‘Estlink-2 repair work starts in the Gulf of Finland’. 22 May 2025.

- 9 House of Commons Library, ‘What is the Joint Expeditionary Force?’, 6 August 2024.

- 10 North Sea Wind Power Hub, Pathway 2.0 Study, 24 June 2024.