Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is no silver bullet but could be a nugget of gold. It is a way to ensure that strategic industries can be both decarbonised and kept in Europe. The EU should instrumentalise the technology to become the world’s carbon banking hub and setter of the global CO2 price. There is currently an opportunity to consolidate CCS innovation in Europe at the expense of Trump’s America. There are however traps ahead, with CCS used to perpetuate and even accelerate the use of fossil fuels. The EU must tread carefully, ensuring that it is panning for gold, not oil.

CCS should have two clear roles. First, it must ensure the survival of critical industries, especially steel, chemicals and cement. Second, it should actively remove carbon from the atmosphere to counter the disastrous consequences of climate change. This Brief proposes a framework for how these two roles should shape the EU’s global partnerships on CCS. There is limited time, money and leverage available, meaning the EU needs to target its efforts to provide clear signals to partners and private companies.

This Brief will cover only industrial CCS and not nature-based solutions for CCS, such as bioenergy from carbon capture and storage (BECCS). Many of these are promising, especially biochar, but their use is often limited to agricultural or waste sectors.

A dose of realism

The original argument behind CCS was to counteract the negative effects of CO2 while maintaining the economic benefits of a fossil fuel-driven model. With CO2 emissions already too high, the argument now extends to the necessity of actively removing CO2 from the atmosphere.

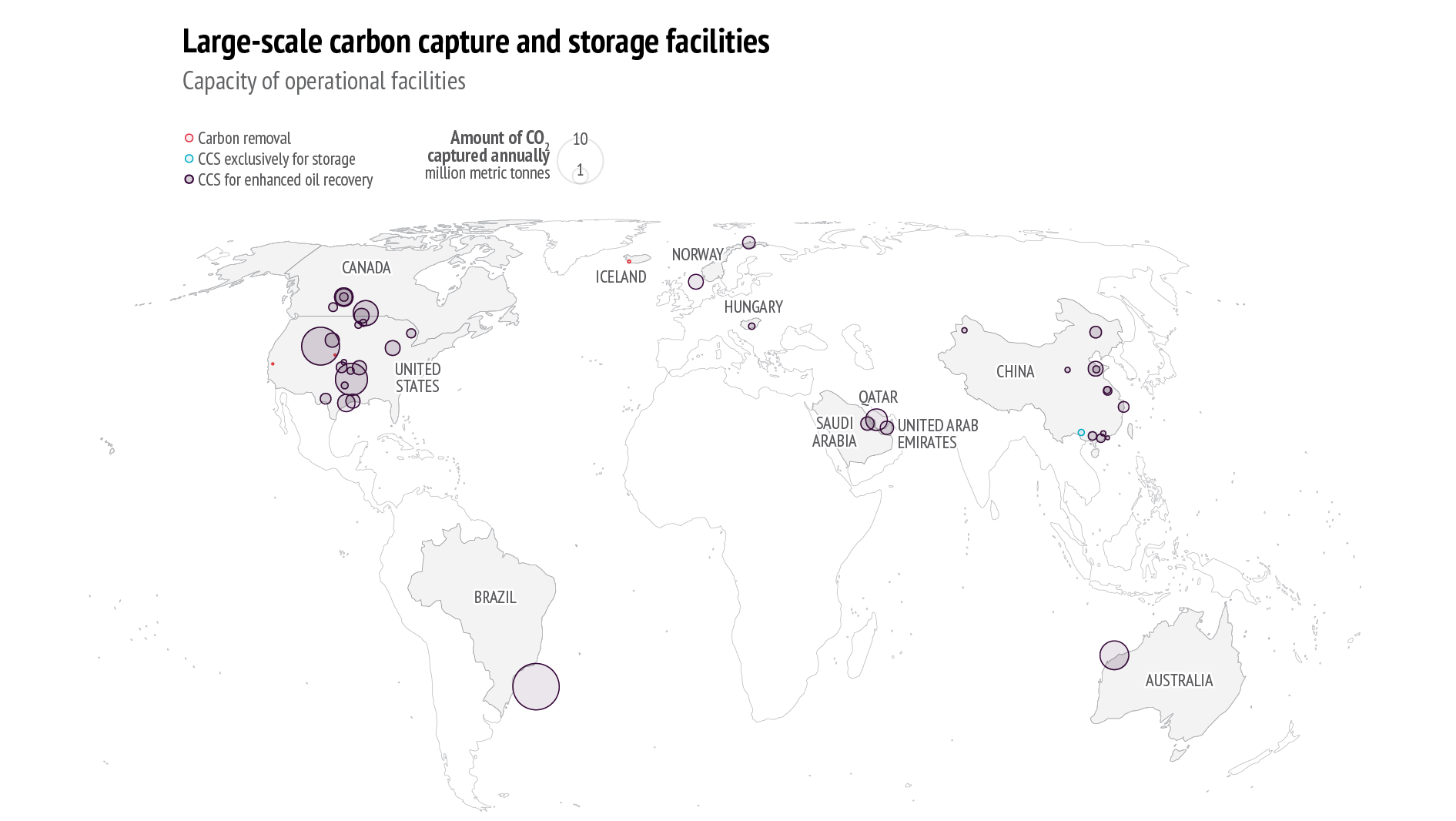

However, there are problems with this narrative. The first is scale. As of 2023, planned and operational CCS plants are expected to withdraw 361 million tonnes of CO2 per annum (mtpa) (1). This is an impressive scale up from 2011 when the figure was roughly 150 mtpa, but still less than 0.01% of global CO2 emissions in 2023 alone (2). CCS is therefore not even coming close to mitigating current emissions let alone removing historic emissions. The problem of scale means that CCS cannot be seen as a silver bullet for rapid decarbonisation especially where cheaper and more efficient technologies exist, notably in electricity generation.

Data: Statista, 'Capacity of operational large-scale carbon capture and storage facilities worldwide as of 2024', 2024

The second is economic viability. CO2 is most commonly captured in flue gases but also via direct air capture (DAC). Capturing CO2 when it is highly concentrated in flue gases requires expensive and often boutique retrofitting of CCS technologies onto the chimneys themselves – if feasible at all. Industrial or power plants are rarely located close to storage facilities, meaning the captured CO2 must first be super-cooled and transported either via pipeline or (more expensively) via ships. Both require new infrastructure and huge amounts of energy. For DAC, the technology can be located close to storage facilities but with CO2 making up just 0.04% of the air, the process is currently technically challenging and highly energy-intensive at scale. The main costs of CCS in 2025 stem from the high energy consumption required but also the construction of new technologically advanced infrastructure. While both challenges can be addressed, reducing energy costs (especially electricity prices) should be prioritised before the upscaling of CCS can be economically viable.

Uses of CCS and their proponents

CCS for enhanced oil recovery

The most common use for CCS is in enhanced oil recovery (EOR). This is where CO2 is captured, pressurised and injected into mature oil and gas fields. Its popularity derives from its ability to significantly increase fossil fuel yields, making extraction from ageing oil and gas fields more profitable. As of 2023, 79% of all CCS projects are dedicated to EOR (3). The world’s largest operating CCS facility, the Petrobras Santos Basin project in Brazil, utilises CCS for EOR. It is also very common in the United States where substantial incentives were afforded to CCS for EOR projects under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). While President Trump may repeal the IRA, its credits to oil and gas companies appear likely to remain intact (4).

EOR is a powerful vector in shaping state dynamics around CCS. Many of its strongest proponents tend to be countries with strong petrochemical sectors, including Canada, the Gulf states, Norway and the US. These countries stand to benefit from CCS not only by sustaining their petrochemical industries but also because technical know-how and storage infrastructure are deeply embedded in the oil and gas industry.

CCS for EOR is not itself a solution to climate change. It is not carbon neutral. Most current uses are limited, covering only the CO2 emitted during extraction (5). At best, employing CO2 from DAC using 100% renewable energy (currently an exceedingly rare scenario) only negates 75% of final emissions (6).The core problem with EOR therefore is that it extracts fossil fuels which are the main cause of climate change. It is not in the interest of the EU to help petrochemicals industries outside the EU extract more fossil fuels and accelerate climate change at the bloc’s expense.

CCS for hard-to-decarbonise sectors

A growing area of development is CCS for hard-to-decarbonise sectors including steel, cement and chemicals. All three are highly strategically important for the EU. These industries require very high temperatures which cannot currently be economically generated from electricity or hydrogen. In all three industries, the carbon molecule itself plays an important role in the production process, further complicating efforts to decarbonise (7). CCS is therefore currently one of the only solutions to both retain these industries and reduce CO2 emissions.

These CCS projects typically tend to be concentrated in countries with heavy industries but also a strong commitment to decarbonisation. Broadly this has meant a focus in the EU, the UK and in East Asia (8). Unlike with EOR, CCS for heavy industry or power generation requires the transport and movement of CO2 for end storage. Since pipelines offer the most economically viable solution, CCS deployments therefore tend to be more localised. In the EU this has led to the development of a storage hub in disused oil and gas facilities in the North Sea, enabling cooperation with the UK and Norway.

CCS for carbon removal

Over the past decade, CCS for negative carbon emissions has emerged on a modest scale. Most commonly this is done through DAC carried out near specific geological formations where the CO2 is permanently stored within the rocks. The value of carbon removal is determined by the reduction of atmospheric CO2, quantified by carbon pricing. As a world leader in carbon pricing, the EU is uniquely well positioned to lead carbon removal efforts, with the added benefit of harmonising a global emissions trading system (ETS).

CCS for carbon removal is limited by geology, as the mineralisation of CO2 into rocks ensures it remains permanently captured. The best-known locations of the vital ‘mafic’ rocks are in Australia, Iceland, India, New Caledonia, Oman, Russia and the US (9). DAC technology is still in its infancy, with only three projects currently capable of removing over 1 000 kg of CO2 from the atmosphere annually. Two of the projects are located in the US (California and Colorado) and a third in Iceland. There are large-scale plans for new sites in Kenya and Iceland, but technological innovation remains focused in North America and Europe. The high energy requirements mean DAC is currently only economically viable in regions with abundant, cheap and stable electricity supplies.

There is clear added value in the EU supporting CCS for carbon removal, especially in attracting clean tech know-how from the US where President Trump has expressed scepticism about carbon removal. There is considerable scope for the EU to lead in research and development, providing expertise to countries which then wish to develop industries around negative carbon emissions. The added advantage would be a harmonisation of carbon markets, obviating the need for more protectionist measures such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).

A clear strategy

The EU should focus on two areas of CCS. The first is in hard-to-decarbonise sectors (steel, chemicals and cement) which are of vital strategic importance to the EU in a dangerous geopolitical environment. The second is in carbon removal where the EU can take advantage of early advancements made in the US to draw in talent and research, strengthening its own geopolitical position during Trump 2.0. These combined strategies intertwine, ensuring a strong strategic industrial sector by reinforcing a global carbon trading system. In clearly shaping its CCS strategy around decarbonisation, the EU also strengthens its hand in climate diplomacy where it can show true leadership in the face of American isolationism.

On CCS for steel, chemicals and cement, the EU should prioritise pipeline transport of CO2 given its cost advantage over shipping. Given the spatial limitations, cooperation and partnerships make the most sense in the immediate neighbourhood of the EU. In particular this means the UK and Norway need to solidify a North Sea CCS hub. Bilateral cooperation should be extended to regional forums to best pool limited resources. Given the cost of CCS, these three carbon-intensive industries must be supported by enhanced protectionist instruments to combat being undercut by cheaper more polluting imports during the transition.

In parallel, the EU should focus on carbon negative technologies, especially DAC, ensuring that it is explicitly recognised as a carbon removal tool powered by clean energy. Alongside current efforts, there is a golden opportunity to relocate clean technologies from the US as it shifts towards climate scepticism. The EU should be aggressive in its attraction of talent for research and development. The technology has potential but needs to be improved from its current state. Within the EU Member States should incentivise DAC, especially as a flexibility solution to intermittent renewables (10). If the industry is successfully developed, Europe could become the carbon bank of the world. It should also look to set the global carbon price through close collaboration with partners.

In practical terms the EU also needs to forge close ties with countries where captured CO2 can be stored. Iceland should already be a strong partner, especially as it is planning to hold a referendum on joining the EU in 2027 (11). The EU could then seek to expand relationships firstly with likeminded partners, such as Australia and certain US states, before drawing in more transactional partners like India and Kenya. A broad alliance would be necessary to support a single carbon price which would underpin the formal carbon market. Such a relationship would be highly advantageous to both parties and would avoid diplomatic fallout such as that which accompanied the CBAM.

In the longer term, a functioning carbon market and a reliable supply of CO2 would form the backbone of an e-fuels industry. Some industries, including aviation, shipping and defence, currently have no viable alternatives to hydrocarbon-based fuels. Such e-fuels within protected supply chains are vital to long-term European security, particularly in the military sector. While CO2 is just one piece of the puzzle alongside green hydrogen, it could become a valuable byproduct of the decarbonisation industry.

Conclusion

CCS is no silver bullet but if cost and technology challenges are overcome, it could be a nugget of gold. CCS is not the main tool in fighting climate change but it has a crucial role to play. The EU should ensure that decarbonising critical industries and achieving carbon removal remain central to its CCS strategy. In the context of Trump 2.0, the EU should seek to encourage the migration of clean tech industries, including CCS, from the US. If leveraged effectively, CCS could help the EU in creating a better climate for all, underwritten by strong partnerships and a unified global carbon market.

References

-

Global CCS institute, ‘Global status of CCS 2023: Scaling up through 2030’, January 2024

-

IEA, ‘CO2 emissions in 2023’

-

Oil Change International, ‘Carbon capture’s publicly funded failure’, 30 November 2023

-

CLF, ‘Deflating the Inflation Reduction Act’, 19 December 2023

-

Wood Mackenzie, ‘Increasing subsidies for anthropogenic CCS for EOR’, 26 July 2024

-

Singh, J. et al., ‘Putting the genie back in the bottle’, International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control, Vol. 139, December 2024

-

Cefic, ‘Chemical industry access to CCS’, November 2024

-

Wood, J., ‘How Japan aims to become a CCS powerhouse’, Spectra, 29 September 2023

-

Ansari, D. et al., ‘Towards a geopolitics of CCS in Asia’, SWP Comment, 9 August 2024

-

Liu, Y. et al., ‘Addressing solar power curtailment by integrating direct air capture’, Science Direct, March 2025

-

‘Iceland’s incoming government says it will put EU membership to referendum by 2027’, Euronews, 22 December 2024