‘Energy is the lifeblood of the military’ the former head of the US army once declared. No army can function without energy.

European militaries face twin challenges. On one side there is war on the European continent. Russia is menacing the border to the east and attempting to rewrite the European security order. Europe must rearm and rapidly. On the other side lie the challenges posed by the global energy transition. From Texas to China, the renewable energy sector is booming. In 2025 clean technology investment surpassed fossil fuels at a ratio of two to one, amounting to 2.2 trillion USD (1). In May 2025, the EU announced that it was within 1% of its 55% carbon reduction target. The global energy transition is firmly underway.

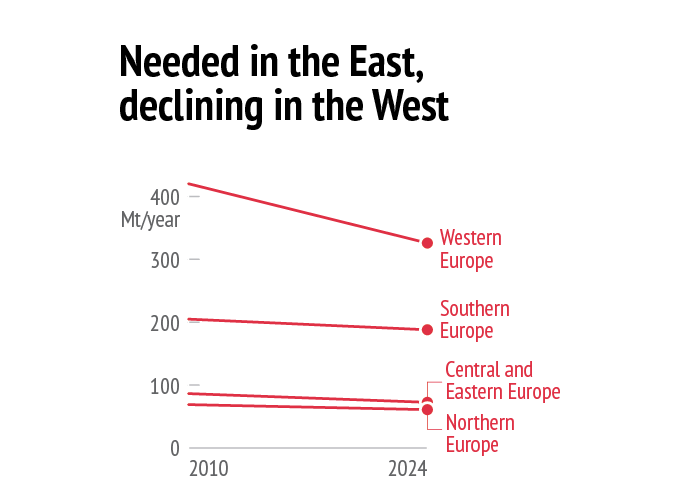

The military consequences of the energy transition are also beginning to materialise. European refining capacity for liquid fossil fuels is in terminal decline, even as demand soars, deepening a dangerous dependency. In Ukraine battery-powered cheap drones now account for around 70% of all battlefield casualties. In this new environment, technologies once seen as optional – such as electronic jamming and high-intensity lasers – are now a military imperative. Solving energy dependencies has become a problem of operational capacity.

The EU has not been blind to these challenges. The Joint Communication on Climate Security aims to address the impact of the energy transition on the military. The Niinistö report flagged several critical vulnerabilities, including Europe’s continued dependency on imported fossil fuels. However tangible progress has been slow to materialise, and rhetoric is not always matched by concrete actions. Political pushback against climate narratives has further obscured the incredible potential of the energy transition to bolster military capabilities and enhance resilience.

This Brief focuses on Europe’s dependencies in liquid fuels and electricity. It aims to offer practical solutions that can be put in place in the short to medium term in response to evolving threats.

Liquid fuel dependency

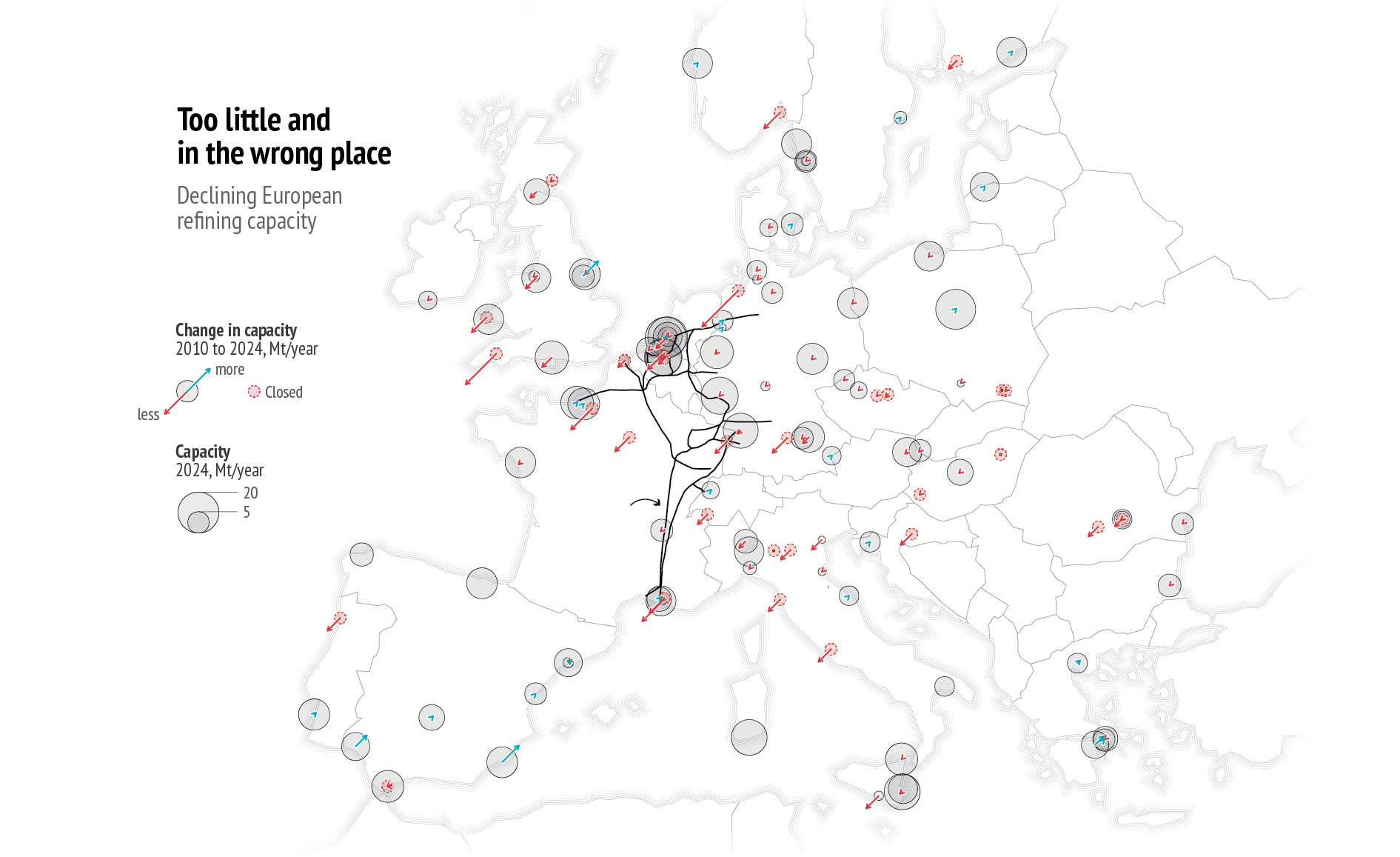

Fuel dependency is a known problem for European militaries. In the short term, supplies are overwhelmingly sourced from outside the EU, making them easy targets in a conflict scenario. Much of the EU’s import, refining and military fuel pipeline capacity is also located in Western Europe, far from any likely land conflict zone in the east (2). In the medium term, domestic supply and fuel capacities are diminishing, primarily due to loss of competitiveness and the ongoing energy transition. Nowhere is this more evident than in the fossil-fuel refining sector, which is in terminal decline.

Data: Concawe, ‘Refinery and Biorefinery Sites in Europe’, 2025; Global Energy Monitor, ‘Global Oil Infrastructure Tracker’, 2025; European Commission, GISCO, 2025

However, demand is rising and will stay high. Orders for heavy military equipment, including equipment envisaged under RearmEU, will extend and deepen liquid fuel dependency for decades ahead. A fighter jet purchased today is expected to last 60 years, while a tank is expected to still be operational in 70 years time.

Aviation demonstrates the scale of military fuel consumption, accounting for an average of 85% of liquid fuel demand. During the Gulf War in 1991, the US burnt in a single day the equivalent of ten times Poland’s daily fuel use in 2025. This was before the advent of modern jets, with an F-35 requiring 60% more fuel than an F-16 (3). The demand for fuel during a peer-to-peer conflict would be huge.

The Joint Communication of 2023 noted the importance of replacing fossil fuels and developing alternative fuel supply chains for defence. The progress report from February 2025, however, demonstrates limited tangible progress. Inertia and short-sighted policy decisions risk leaving the military reliant on an expensive and vulnerable network of storage, refineries and infrastructure maintained exclusively for its own use.

The EU needs to commit to a path and run with it. For a successful transition, new solutions must complement existing systems. In the short term, the clearest solution is to scale up biofuel production and expand fuel pipeline infrastructure to reduce reliance on imported fuels. In the medium term, Europe should invest in developing a decentralised network of domestic synthetic fuel production capable of supplying standardised fuel across the continent.

Biofuels represent a domestic source of hydrocarbons within Europe. Their production tends to be geographically dispersed, which enhances resilience and constitutes an important operational strength, especially in the east. According to the European Commission, there is also substantial potential to expand biofuel production without affecting agricultural production (4). While biofuels were traditionally blended with existing fossil-based fuels, they are increasingly used in higher and higher volumes in military as well as civilian aircraft. The UK recently conducted tests using 100% biofuels to power its Typhoon jets, while Norway has run similar tests on the F-16 (5). However. standardisation remains a problem with biofuels. Under NATO’s single fuel policy the same fuel should be applicable to all NATO aircraft. Compounding the issue are additional concerns around cost and scalability, with European biofuel production plateauing in recent years. Biofuels therefore are best understood as offering a transitional solution for the military as fossil fuels decline.

In this transition too, there is a need to expand the fuel pipeline system in Europe. The Central European Pipeline System (CEPS) provides a model. It serves civilian aviation in peacetime and is reserved for NATO in wartime. A similar dual-use model is needed in Eastern Europe. Pipelines have considerably greater utility to the military as they can be easily repaired, transport high volumes at speed and connect facilities. The CEPS demonstrates how military and civilian infrastructure can operate in tandem, creating synergies and cost efficiencies. Biofuels now account for 8% of the fuels transported by the CEPS for civil aviation use. Alongside the security benefits this brings for military operations, sustainable aviation fuels also help to reduce the carbon footprint of a sector that is hard to decarbonise, accomplishing two goals symbiotically.

In the medium term, synthetic fuels offer the most sustainable and scalable path to ensuring a reliable domestic supply of hydrocarbons for military use. In June 2025, INERATEC opened the first commercial-scale synthetic fuel plant in Germany, marking a significant step forward in expanding production capacity beyond the numerous smaller power-to-fuel facilities scattered across Europe (6). Such volumes could begin to provide a viable source of domestic hydrocarbons for the military. The smaller scale and decentralised nature of synthetic fuel plants is a key strength, ensuring the future fuel supply system is composed of hundreds of distributed sites rather than a handful of critical chokepoints. Synthetic fuels are also standardised in line with the single fuels policy.

Synthetic fuels require short and simplified logistical chains, as the technology only really requires electricity alongside access to water. With cheap and abundant electricity, hydrogen can be produced via electrolysis, while CO2 can either be drawn out of the air or captured from industrial sources. Such a system embodies the goal of a successful energy transition, integrating energy innovation with enhanced operational resilience. Synthetic fuels should therefore be a medium-term objective for European militaries. However, achieving this will require substantial upfront investment and bold EU-level decisions to incentivise and accelerate their production.

Biofuels and synthetic fuels represent highly attractive options for building a resilient and secure hydrocarbon supply chain for the military. Their widespread deployment, however, would require the availability of suitable fuel infrastructure for distribution and storage. While both fuel types originated in the civilian sector, driven by domestic EU regulations relating to the Green Deal, there is significant potential for greater synergies and cooperation, with the military well placed to become an important customer for synthetic fuels. Collaboration with other key sectors such as aviation, automotive and chemicals would help ensure that the military does not become a captive market for alternative fuels.

Nevertheless, there remains a need for clear political communication about the trade-offs involved. Biofuels, and especially synthetic fuels, are unlikely to be cost-competitive with fossil fuels in the near term, particularly while the latter fail to factor in any broader societal or climate costs. Prices will undoubtedly fall as efficiency savings are found, but the driving factor behind military investment in alternative fuels should be operational security.

Electricity dependency

Militaries require reliable electricity supplies. Demand is only likely to grow as energy-intensive weaponry such as anti-drone lasers and signal-jamming equipment become even more widespread, alongside the broader electrification of military mobility. Currently military bases tend to connect to local grids with diesel generators for backup. However, such a system is highly vulnerable, with a recent Military Review paper identifying fuel supply as a ‘critical vulnerability’ in the event of a peer-to-peer or near-peer conflict (7). A US military study found that for every 24 fuel convoys between Iraq and Afghanistan, there was one fatality (8). Moreover, such energy systems face challenges in sparsely populated regions like the High North, or in areas where local electricity infrastructure is either underdeveloped or vulnerable to attack.

This issue has been acknowledged in the Joint Communication, which notes the impact of the energy transition on military energy systems. The progress report further highlighted projects with a strong emphasis on energy efficiency – an easy win for enhancing capacity and reducing costs. However, more needs to be done to ensure energy supply. The EU should also seize the opportunity to take advantage of the changing mood music in the US, which has been at the forefront of military electricity deployment. The solution is to pick up where the Americans left off.

The US military, with a strong track record in energy provision and global power projection, has focused on deploying microgrids. The principal justifications have been enhanced resilience, reduced costs and enhanced capability. A military research paper has also highlighted an additional advantage: microgrids can be highly mobile, a vital strength in conflicts where mobility is critical to survival (9).

In the short term, the most promising options continue to lie in solar and wind power. In the civilian sector the mining industry has long faced the challenge of bringing electricity to remote locations. Recently Chinese companies have utilised solar energy paired with battery storage systems to solve the problem (10). Portable battery technologies, supported by solar or wind generation, are currently capable of providing scalable energy independence to smaller, more flexible bases or those located in remote or difficult environments. Intermittency remains a problem however.

Small modular nuclear reactors (SMRs) have been gaining traction globally as they provide reliable steady flows of off-grid electricity to data centres and industrial hubs. The US military has also begun testing mobile SMRs, with Project Pele developing reactors compact enough to be transported in shipping containers (11). Beyond nuclear power, the US Air Force has trialled a geothermal energy project in California capable of operating independently of the grid. In Europe, however, innovation remains confined to the civilian sector, despite the clear potential of these technologies to provide continuous supplies of heat and electricity.

Technology neutrality is vital for breaking electricity dependency. Different solutions offer varying capabilities, with solar energy being especially versatile and scalable while geothermal or nuclear technologies, despite certain limitations, can deliver a high output and steady power supply. Above all, the military should play a role in driving progress in the civilian sector. Existing solutions and unresolved challenges alike present clear opportunities for mutual benefit. In this endeavour, time is the only limiting factor.

References

- 1 IEA, ‘Global energy investment set to rise to $3.3 trillion in 2025’, 5 June 2025.

- 2 Stoop, R. et al., ‘Securing European military fuels in a tense geopolitical environment’, HCSS, April 2025.

- 3 Briefing with European military officials, June 2025.

- 4 Motola, V. et al., ‘Advanced Biofuels in the European Union’, European Commission JRC, 24 October 2023.

- 5 RAF, ‘RAF defends UK’s skies using sustainable energy fuels’, 14 August 2024.

- 6 INERATEC, ‘INERATEC opens ERA-One’, 3 June 2025.

- 7 Barry, N. and Santoso, S., ‘Modernizing Tactical Military Microgrids to Keep Pace with the Electrification of Warfare’, Army University Press, November 2022.

- 8 American Security Project, ‘Defense Energy’.

- 9 Army Doctrine Publication, ‘Operations’, 31 July 2019.

- 10 ‘The skyrocketing demand for minerals will require new technologies’, The Economist, 26 February 2025.

- 11 Patel, S., ’Project Pele, DOD’s HTGR mobile nuclear reactor, breaks ground’, Power, 25 September 2024.