You are here

Sanctions, conflict and democratic backsliding

Introduction

Until the annexation of Crimea led the EU to impose sanctions on Russia in 2014, few Europeans were aware that the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) entailed the imposition of sanctions. Member States had been enacting sanctions jointly since the early 1980s; however, in the initial decades, European measures had modest economic consequences. Moreover, target countries were mostly located in remote corners of the world, and their volume of trade with the EU was often negligible. But this state of affairs has changed. It has become abundantly clear that sanctions are the most frequently deployed tool of the CFSP to react to foreign policy crises (1), and that the measures imposed are increasingly economic in nature. Targets now include global powers. In particular, the current raft of sanctions enacted against Russian targets in response to the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 stands out as an unexpectedly robust response, adopted in several waves that succeeded one another at exceptional speed. The increasing centrality of EU sanctions in the CFSP raises a number of questions: in which situations are sanctions applied, and with what outcome? What sanctions are best tailored to address different kinds of situations? What are the implications of the EU’s increased use of sanctions? These questions are particularly pressing for two reasons. Firstly, while the EU is not new to the sanctions field, it still has limited experience in imposing and managing restrictions of a financial and economic nature outside the aegis of the United Nations (UN). Moreover, the vast majority of EU Member States do not have a record of sanctions imposition in their national foreign policy traditions. Secondly, most sanctions scholarship focuses on the sanctions practice of the United States and the UN, both of which differ from that of the EU in important ways. This Brief presents an analysis of the circumstances in which sanctions are employed, what rationales guide their imposition and what impacts we can expect, focusing on the two types of situations in which the EU usually applies its measures: violent conflict and democratic backsliding. It goes on to offer some insights to guide policy on the way forward.

EU sanctions policy: An overview

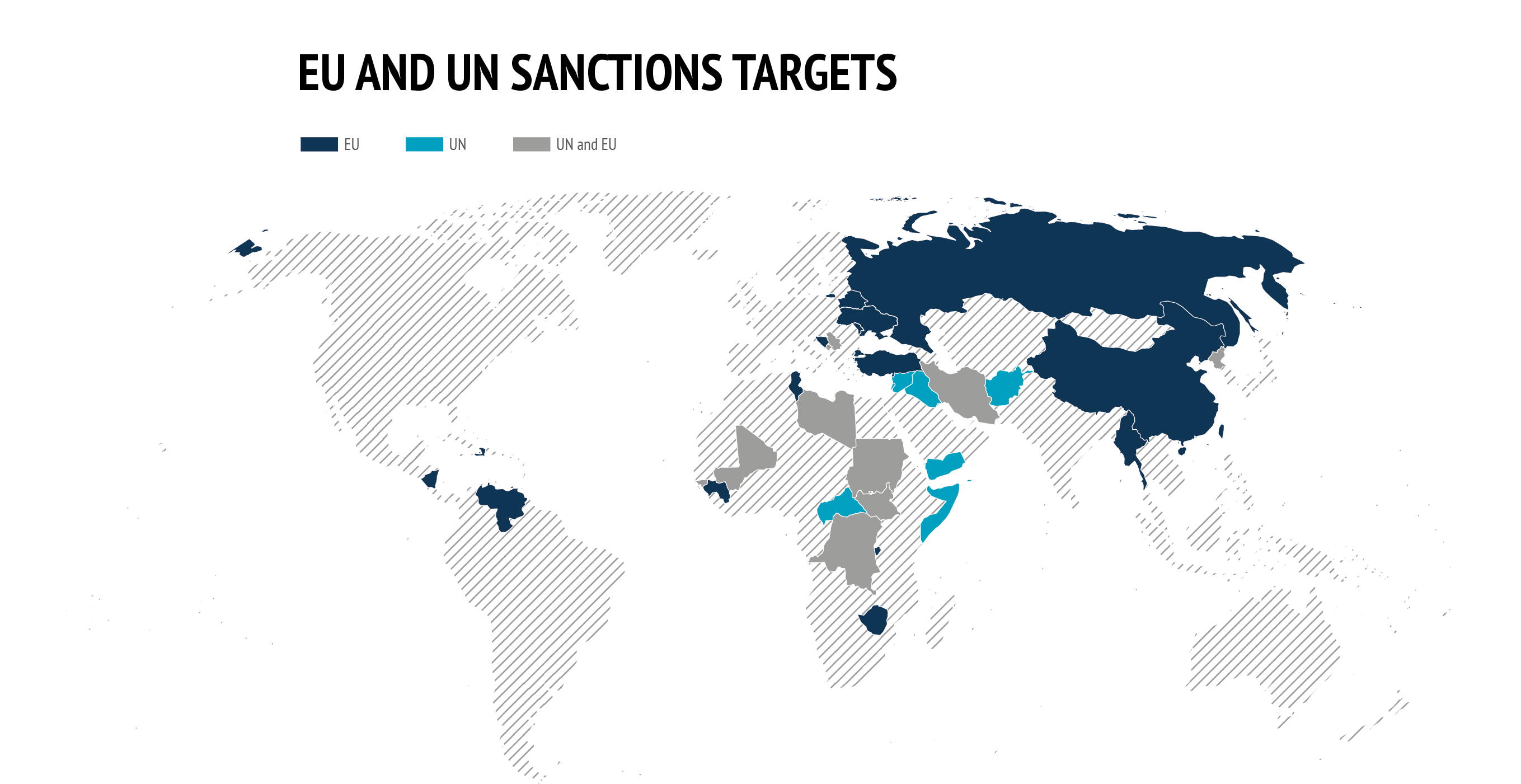

Data: sanctionsmap.eu, 2022; European Commission, GISCO, 2022

‘The Basic Principles on the Use of Restrictive Measures (Sanctions)’, a programmatic document adopted in 2004, announced the Council of the European Union’s intention to enact autonomous sanctions to uphold respect for human rights, democracy, the rule of law and good governance, and to fight terrorism and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) (2). While the term ‘autonomous’ is understood here to signify those restrictions agreed by the EU in the absence of a UN Security Council (UNSC) mandate, EU and UN practice are closely interlinked. The circumstances in which the EU actually imposes sanctions depend on whether the UN takes action or otherwise. Like the UN, the EU frequently applies sanctions in situations of armed conflict. However, since the UN Charter empowers the UNSC to impose mandatory measures in situations which endanger international peace and security, it often addresses violent conflict with sanctions. The existence of UN measures obviates the need for EU autonomous sanctions. Still, Brussels sometimes complements UN measures with additional restrictions that reinforce those agreed in New York (3). By contrast, the UN lacks a mandate to address situations of democratic regression, such as coups d’état. This constitutes the main scenario that attracts the imposition of sanctions by the EU, alongside the United States and other partners. Warfighting and democratic backsliding are almost invariably accompanied by human rights violations; thus, the protection of human rights features prominently among justifications adduced for sanctions enactment. In the context of violent conflict, human rights abuses are conflated with breaches of regression, the emphasis lies on the breach of human rights that are closely related to the democratic process, such as the freedom of expression, demonstration or association (4). Separately from the sanctions regimes agreed in reaction to country crises, the EU recently adopted a sanctions regime in support of human rights, which takes a thematic or ‘horizontal’ format, and lists a diverse array of individuals and entities responsible for perpetrating human rights violations taking place outside (or in the absence of) major international crises (5).

The EU also imposes sanctions to tackle two kinds of threats similarly addressed by the UN: terrorism and the proliferation of WMD (6). A point of divergence between Brussels and New York concerns sanctions against corruption and cyberattacks. Unlike the UN, in the aftermath of the Arab Spring and Euromaidan uprisings the EU enacted sanctions regimes for the misappropriation of state funds. Finally, the recent adoption of a sanctions regime targeting the perpetrators of cyberattacks has enhanced the EU cybersecurity toolbox.

The protection of human rights features prominently among justifications adduced for sanctions enactment.

In terms of geographical distribution, CFSP sanctions targets are concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East, similar to the distribution of UN sanctions targets. However, the EU differs from the UN in its strong focus on its neighbourhood. This is particularly true for its Eastern neighbourhood, where it displays a heightened sensitivity to developments endangering democratic governance or the security of its own citizens (7). In the rest of the world, autonomous CFSP sanctions typically respond to democratic regressions accompanied by the violent repression of civilians, like the crisis that has afflicted Nicaragua since 2018. More often than not, CFSP sanctions are wielded jointly with the US, frequently following its lead. Still, humanitarian law, while in the case of democratic EU sanctions practice remains more modest in scope than Washington’s: the EU selects a smaller range of targets, its economic and financial restrictions are less far-reaching and its measures are not intended to display the severe extraterritorial effects that characterise US practice (8).

Design and sequencing

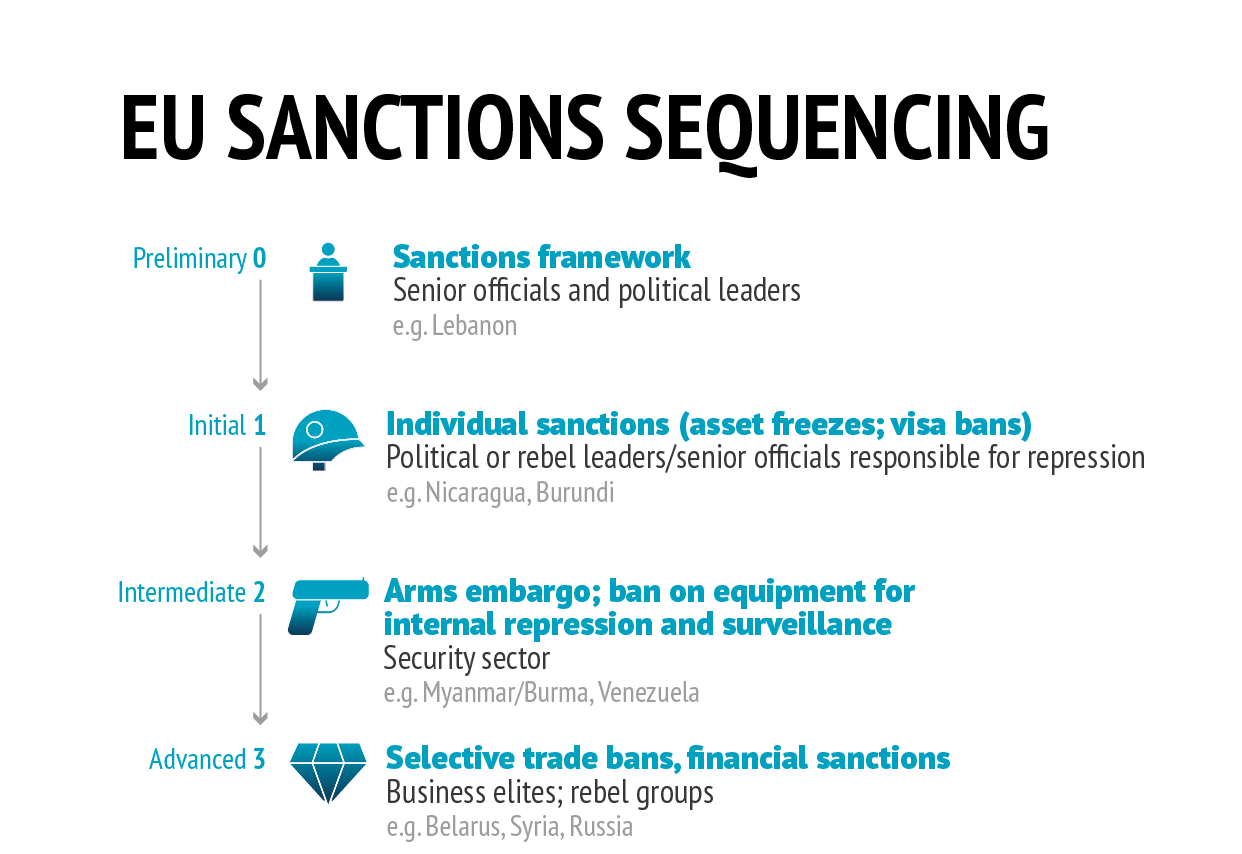

Although no official document spells out escalation strategies, a standard sequencing can be discerned from EU practice. The beginning of the actual imposition of sanctions is sometimes preceded by the passing of the legislation enacting sanctions – a so-called ‘sanctions framework’ – with an empty annex, indicating that the Council is ready to include entries but that it will initially refrain from doing so, in the expectation that the crisis can be resolved and make designations unnecessary. This practice, common in the UN context, equates to a threat of sanctions imposition as it gives the target one last chance to desist from the behaviour condemned before sanctions are enacted. If this fails, a first round of designations materialises. The first stage in the actual sanctions exercise consists of the blacklisting of a number of individuals on which a visa ban and an asset freeze is applied, often accompanied by a few companies and agencies. The number of designations increases progressively in subsequent waves. A second stage includes an embargo on the supply of arms, equipment for internal repression and surveillance and dual-use items, in addition to a ban on the provision of related services and of any form of military cooperation. The next stage in the escalation prohibits the export or import of certain products and commodities, and encompasses the imposition of financial sanctions. This may take the form of trade bans or the blacklisting of state companies dealing with energy and commerce, key public entities like the central bank, and even commercial harbours. While the EU traditionally exercises caution in moving from the second to the third stage, it has crossed this threshold with increased frequency over the past decade (9). Different targets are hit in each phase: the first stage narrowly focuses on key political figures, the second is geared towards the internal security establishment, and the third concerns state and business elites while entailing broader ramifications for society.

In the current EU sanctions landscape, instances of all these escalation stages can be found. The sanctions framework adopted by the EU on Lebanon in July 2021 is not accompanied by any designation (10). Within each stage, different levels of severity are observable. Sanctions on Burundi are frozen at the initial stage, featuring only 4 designations (11). Nicaragua has already been subjected to a second round, which saw the expansion of its short blacklist from 14 to 21 individuals plus three official entities (12). Sanctions on Myanmar/Burma and Venezuela are examples of the second stage, where the export of technologies with military, repressive or surveillance applications is banned across the board (13). The sanctions on Belarus have reached the third stage of escalation, as they affect trade across a range of items like fertilisers, cement, minerals, iron and steel, machinery, wood and tobacco, in addition to a flight ban (14). Sanctions on Syria are even more stringent, with measures covering gas, petrol products and a range of financial restrictions (15).

Sanctions are rarely imposed with clearly formulated goals.

The sanctions package launched in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine since February is exceptional in that it deviates from this general pattern. The first wave, adopted following the Russian Duma’s recognition of the breakaway republics in Donbass and prior to the military campaign, focused heavily on financial restrictions. One of the most far-reaching financial measures, the exclusion of a number of Russian banks from the SWIFT system, was also imposed at the initial stage. Trade sanctions ensued very quickly after the launch of the military campaign, including some unprecedented measures such as the withdrawal of Russia’s Most-Favoured-Nation status, which entails tariff reductions for members of the World Trade Organization. In contrast to most sanctions packages, the measures had been agreed in the context of the Group of Seven (G7) before they were adopted by the Council, which explains why the escalation steps are at variance with regular practice. Yet, the most distinctive feature of the sanctions against Russia was the celerity with which sanctions waves succeeded each other, eclipsing the speed with which the EU sanctions toolbox was deployed in reaction to the eruption of the Syrian war in 2011 (16).

In view of the different types of situations in which the EU imposes sanctions, this Brief turns to the question as to when and how sanctions can be applied with positive results. The two most typical situations attracting both EU and UN action are surveyed: violent (mostly intra-state) conflict, and democratic backsliding. The fight against terrorism and WMD, goals shared by both organisations, follow at a distance: terrorism designations feature on a horizontal list, and there have only been four instances of WMD sanctions (against North Korea and Iran for nuclear proliferation and Syria and Russia for chemical attacks) (17). Such analysis is particularly pertinent in view of the often-repeated claim that sanctions rarely achieve their objectives, or that they plainly ‘do not work’. Curiously, sanctions are rarely imposed with clearly formulated goals (18). Legislation enacting restrictions, and the declarations and press releases that accompany them, do not normally spell out the objectives they pursue. Instead, they lay out the circumstances that prompted the adoption of sanctions – routinely some kind of norm violation –, the criteria that justify the designation of individuals and entities – typically their responsibility in the condemned actions – and entries on the blacklist fulfil the designation criteria.

While legislative documents feature abundant information on these issues, they do not stipulate what exactly the sanctions are meant to achieve, or what actions ought to be undertaken by the designees in order to be removed from the blacklist. The reasons for lifting sanctions may be spelled out at a later stage. The lifting of the sanctions package imposed on Russia in response to its annexation of Crimea and destabilisation of Ukraine in summer 2014 was conditioned on the full implementation of the Minsk II Agreement, which was not signed until March 2015. The absence of explicit goals in the legislative acts complicates their assessment as it deprives observers of a clear yardstick for measurement (19).

Sanctions and armed conflict

The use of sanctions is intimately linked to armed conflict. Its emergence as an instrument for conflict management can be traced back to the creation of the League of Nations in the aftermath of World War I. US president Woodrow Wilson, who masterminded the organisation, conceived of sanctions as a substitute for the use of force, as manifested in his famous quote: ‘apply this economic, peaceful, silent, deadly remedy and there will be no need for force’ (20). Accordingly, the Covenant of the League foresaw the automatic application of a full embargo on any country that committed aggression against another. Yet, the idea that sanctions could replace military force to attain objectives such as the statement of reasons indicating how each of the repulsion of aggression dissipated quickly. The Charter of the UN, the League’s

successor organisation, introduced more flexibility to the rigid sequencing prescribed by the Covenant, giving leeway to the Security Council to wield sanctions in anticipation of, in substitution of, or in combination with military force. Throughout the 20th century, the severance of economic and financial relations with an adversary have generally accompanied rather than replaced warfighting. When, shortly after the end of the Cold War, Iraq invaded Kuwait in a textbook example of inter-state aggression, the UNSC immediately agreed a mandatory embargo. However, the embargo was quickly superseded by an UN-mandated military mission to expel Iraqi forces from Kuwait, leading observers to complain that sanctions had not been given a chance to deploy their effectiveness before force was used (21).

Nowadays, the main tool applied to violent conflict is the arms embargo, which bans the supply of weapons, ammunition and related materials to the

contending parties. Their rationale is to curtail the availability of weapons in conflict zones, thereby limiting conflict intensity (22). However, the idea of putting an embargo on all warring parties was soon discredited as in practice its theoretically even application tends to favour one party over the other. A most obvious example was the former Yugoslavia, where the location of defence industrial sites in the Serbian heartland ensured access to arms production for Serbia’s allies while the UN embargo prevented parties like the Bosnian Muslims from importing weapons. As a result, the UN moved to apply them against one party to the conflict, thus ‘taking sides’.

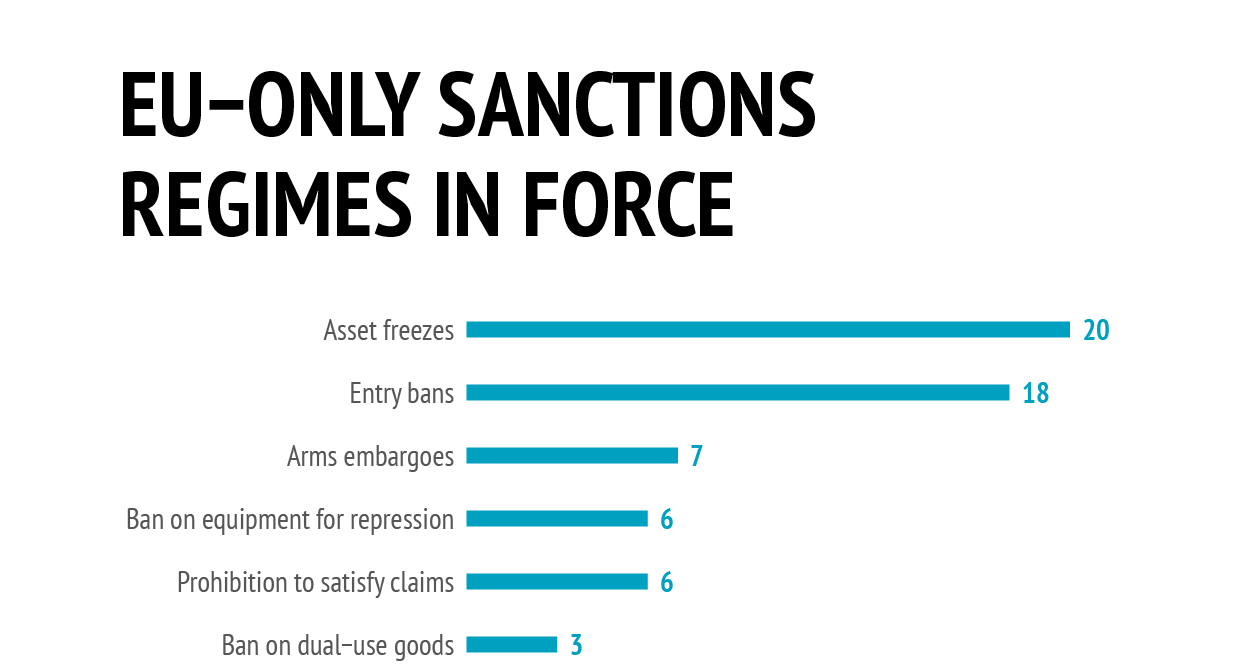

Data: sanctionsmap.eu, 2022

The differentiated treatment of contending parties was replicated when other measures were applied in conflict situations. This was notably the case with commodity embargoes, which became common during the 1990s. Trade in illegally extracted diamonds was banned in order to deprive warring groups like the rebels in Angola and Liberian forces in Sierra Leone of their sources of funding. These measures addressed a key enabler of violent conflict, given that the exploitation of natural resources constitutes a lucrative trade that discourages the parties from ceasing hostilities (23).

Sanctions are devised to avoid inflicting economic deprivation on an often powerless population.

Visa bans can interfere with efforts to raise funds or acquire weaponry when foreign travel is required: the ability to travel often enables the conduct of campaigns for garnering political backing overseas (24). The obstructive effect of travel restrictions on such activities is confirmed by targets’ own accounts. Noting that ‘not being able to travel is a big political handicap’, politicians designated under UN and EU sanctions during the conflict in Côte d’Ivoire of 2010-11 claimed that they ‘could have exported the fight to the sub-regional level’ in the absence of travel bans (25). Another way of maximising the effectiveness of sanctions against individuals is to deploy them in the context of international mediation efforts. Designations, the threat thereof, or the promise of their removal, can create incentives for political actors to unblock stalled negotiations, fostering agreement among hostile parties. Both sanctions and sanctions threats have been employed fruitfully to that effect: individual designations promoted participation in the talks that led to the signing of the 2015 Libyan Political Agreement which unified divided state institutions (26). Yet, sanctions remain underexploited tools in mediation.

Sanctions and democratic backsliding

Sanctions against democracies tend to be more effective in achieving political concessions than those applied against non-democratic regimes. Democratic systems are more sensitive to sanctions, as their leaders depend on popular support for re-election, which makes them more averse to endangering their country’s wealth and incurring reputational costs associated with being at the receiving end of a sanctions regime. However, this intuitive insight is of limited use to policymakers given that most sanctions are imposed on non-democratic countries, reflecting the principle of ‘democratic peace’ whereby democracies typically settle disputes with one another without recourse to coercion (27). In an effort to tease out how sanctions affect domestic political dynamics in the targeted countries, some observers scrutinise the operation of sanctions with reference to the internal politics of the targeted state. Instead of regarding sanctions as an interaction between the sender and target leadership, they focus on the effect that these have on domestic actors and on how they alter their calculations. While the efficacy of sanctions in destabilising autocratic regimes is generally modest (28), the type of autocracy prevailing in the target country influences the likely impact of sanctions. As autocracies vastly differ from each other, sanctions impact their internal workings differently. On account of their intrinsic characteristics, regimes that rely overwhelmingly on an individual leader are considered to be most vulnerable to sanctions, as they crumble once the leader leaves office. Military-led autocracies are also seen as vulnerable to sanctions because the military establishment opts to withdraw from politics as soon as splits surface in their leadership. By contrast, single party regimes rely on solid institutional structures capable of managing the impact of sanctions (29). However, the potential of economic sanctions to destabilise an authoritarian regime does not equal their ability to promote compliance with sender demands, not even when the desired outcome is a transition to democracy. Deposed autocrats are often replaced by new dictatorships (30).

Equally important is the composition of those key elites which support a specific leadership. In the absence of democratic legitimation, autocrats rely on the backing of selected actors – military, ethnic, religious, or business elites – which in turn profit, economically or politically, from their association with the rulers. The survival of autocratic regimes is conditional on their continued support (31). This makes elites in autocracies an ideal target for the kind of sanctions imposed by the EU, namely ‘targeted sanctions’. Targeted sanctions are designed to be selective in their effects, and specifically impact certain individuals, entities or economic sectors rather than the economy as a whole. Unlike comprehensive embargoes, targeted sanctions are devised to avoid inflicting economic deprivation on an often powerless population. From that point of view, targeted sanctions use the same coercive means as comprehensive embargoes, but reverse their logic. The tools employed, which include individual sanctions, selective trade embargoes, transport and financial bans, are apt to affect those elites implicated in the condemned actions.

The EU displays a higher propensity to lift sanctions than other senders.

Thus, sanctions are often formulated to encourage key elites to withdraw support from the condemned leadership and their policies. Restrictions on elite members obstruct their business activities, making their association with the rulers less lucrative – or even costly – and tainting them with the stigmatisation already attached to the regime. Hence, senders seek to alter the incentives of the key elites, rather than proceed by disadvantaging the leaderships or impoverishing the population (32). This said, targeted sanctions feature different degrees of discrimination. Individual sanctions are narrowly targeted to affect individuals identified as responsible for abuses. Bans on private entities, equipment or commodities tend to have ramifications beyond the group they intend to affect. Finally, bans on energy, transport hubs like harbours and key state entities like the central bank have broad consequences for the target country’s economy and society (33). Therefore, in order to mitigate possible humanitarian effects on vulnerable segments of the population, EU sanctions legislation is invariably endowed with specific humanitarian exceptions (34).

Can sanctions do better?

Although the rationale behind sanctions appears logical, their application is generally considered unsuccessful. While scholarship offers plentiful explanations for the perceived failure of sanctions, some of these derive from flaws in their design and management and appear particularly relevant for CFSP practice.

Firstly, there is often a mismatch between the situations in the context of which sanctions are applied and the type, scope and timing of the measures selected. The CFSP sanctions formulation and sequencing follows a similar template when applied to situations of violent conflict or democratic backsliding. However, as seen above, different situations require different measures and targeting policies. More thought could be given to the tailoring of the packages depending on whose incentives need to be altered to promote compliance. Improving the alignment between the measures to be adopted and the context in which they need to display their effects necessitates better planning (35).

This requires, in turn, enhancing foresight capacities to conduct an analysis of the relevant elites in the target countries, their role in society, their funding sources and their ties to the leadership in anticipation of sanctions enactment. This would mitigate the ‘ad-hoc’ quality that afflicts sanctions design efforts that often unfold amidst quickly evolving circumstances.

In addition, insufficient use is made of sanctions threats, which are considered as the most cost-effective way of wielding sanctions as they can elicit concessions without requiring enactement. Despite evidence that the threat of sanctions tends to be more successful than their imposition (36), sanctions threats are rarely issued publicly. Moreover, numerous blacklisted individuals report having learned about their designation from the news, suggesting that they had not been approached to negotiate an accommodation before sanctions were enacted (37).

Moreover, the goals of sanctions suffer from a certain indeterminacy. The absence of explicit goals in sanctions-enacting legislation allows the Council ample discretion in settling the controversy with the target. However, that very discretion can discourage targets from complying as they lack an indication of the circumstances under which sanctions would be removed, a situation which may foster the belief that sanctions will persist irrespective of their behaviour. In reality, the opposite is true: the EU displays a higher propensity to lift sanctions than other senders. Washington, and in particular the US Congress, is reluctant to lift sanctions before full compliance is in place for fear that targets will cease to comply in the absence of pressure. By contrast, the EU has repeatedly demonstrated its readiness to terminate sanctions in the face of visible progress made by target leaderships short of full compliance, reinstating trade and aid likely to facilitate further progress (38).

Crafting a procedure based on the drafting of a ‘roadmap’ adjusted to the situation to be addressed could facilitate the phasing out of sanctions (39). Accordingly, the EU could draw inspiration from its own practice of reinstating countries from the African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) group suspended for breaches of human rights or democratic rule. Under the ACP-EU Partnership Agreement, the EU routinely holds consultations with leaders under suspension in order to agree on a roadmap. The definition of tangible yardsticks embedded in the roadmap establishes clear parameters against which progress can be measured, reassuring targets about the reversibility of the sanctions. Progress in meeting the milestones on the roadmap is rewarded with the lifting of measures, a method christened the ‘gradual and conditional approach’ (40). The phasing-out procedure foresees the dispatch of regular monitoring missions to verify progress and help address possible deficits. The meticulously structured lifting process foreseen in the EU-ACP context contrasts with the breadth of discretion granted to the Council in the termination of CFSP sanctions. The detailed designation criteria in CFSP legal acts are unmatched by ‘de-listing’ criteria featuring information on the action to be taken for designees to be removed from the list. Regrettably, de-listing of designees is overwhelmingly driven by annulments mandated by the Court of Justice of the EU, rather than by behavioural change (41). In the spirit of the ‘gradual and conditional approach’, phasing-out strategies could be devised for CFSP sanctions regimes setting concrete demands whose fulfilment can be linked to the progressive lifting of restrictions.

Lastly, the communication dimension ought not to be forgotten. Little is known outside Brussels circles of the amount of time and effort devoted to the formulation of humanitarian exemptions, target selection and ensuring the legal robustness of sanctions. In spite of the challenge of communicating to the public in the face of media monopolies dominating the information arena in target countries, the EU needs to publicise the way in which CFSP sanctions policy selectively targets responsible elites rather than the population at large.

Lessons for and from the sanctions on Russia

The current sanctions regime against Russia remains an exception in the CFSP record. It was applied in an atypical scenario: that of an international aggression rather than of the customary intra-state conflict or democratic backsliding. Accordingly, an unprecedented level of sanctions cooperation was achieved among a group of mostly Western allies encompassing G7 members – the EU, the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Japan – as well as Australia and South Korea (42). This collection of ‘like-minded’ countries sees itself as substituting the action that the UNSC is prevented from taking due to the Russian veto.

The analysis of sanctions application presented here does not augur well for the success of the current package in halting military advances. The pace at which sanctions display their effects make them unsuitable to constrain military force, although – paradoxically – this is the type of breach that attracts the most decisive action by the EU. Indeed, sanctions have been usefully employed to reduce lethality and facilitate an end to conflicts characterised by protracted military stalemate.

Nevertheless, the current sanctions response is significantly boosting the EU’s agility and efficiency in terms of sanctions preparation and implementation and extra-European coordination. In terms of CFSP sanctions formulation, the current episode seems to consolidate a ‘bifurcation’ of procedures. The standard procedure for sanctions initiation normally emanates from the relevant geographical Council working party, and is concretised by the RELEX working party before it is submitted to the Council for adoption (43). In contrast, both the 2014 and the 2022 EU sanctions packages against Russia were decided and handled at the highest level both internally and externally, notably in the G7 context. Coordination with extra-European countries even reached the previously uncharted domain of sanctions implementation: the Commission set up a ‘Freeze and Seize’ task force that cooperates with the G7’s own task force ‘Russian Elites, Proxies, and Oligarchs’ (44). The hope is that, instead of consolidating a procedure whereby a different decision-making path is selected depending on the importance of the target, the current experience of sanctions against Russia can set a new standard that allows future sanctions efforts to benefit from the speed, dedication and unprecedented level of coordination devoted to addressing the invasion of Ukraine.

References

1. Bendiek, A., Ålander, M. and Bochtler, P., ‘CFSP: The capability- expectation gap revisited’, SWP Comment No 58, SWP, Berlin, 2020 (https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/publication/cfsp-the-capability- expectation-gap-revisited/).

2. Council of the European Union, ‘Basic Principles on the Use of Restrictive Measures (Sanctions)’, 10198/1/04, REV 1, Brussels, 7 June 2004 (https:// data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-10198-2004-REV-1/en/pdf).

3. Biersteker, T. and Portela, C., ‘EU sanctions in context: Three types’, Brief No 26, EUISS, July 2013 (https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/ files/EUISSFiles/Brief_26_EU_sanctions.pdf).

4. Portela, C., ‘EU sanctions as a foreign policy tool’ in Gareis, S., Hauser, G. and Kernic, F. (eds.), Europe as a Global Actor, Budrich, Opladen, 2012.

5. Portela, C., ‘A blacklist is (almost) born: Building a resilient EU human rights sanctions regime’, Brief No 5, EUISS, April 2020 (https://www.iss. europa.eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/Brief%205%20HRS.pdf).

6. Charron, A., UN Sanctions and Conflict: Responding to peace and security threats, Routledge, Abingdon, 2011.

7. Portela, C., ‘Sanctions and the European Neighbourhood Policy’ in Demmelhuber, T., Marchetti, A. and Schumacher, T. (eds.), Routledge Handbook on the European Neighbourhood Policy, Routledge, Abingdon, 2017.

8. Portela, C., ‘Creativity wanted: Countering the extraterritorial effects of US sanctions’, Brief No 22, EUISS, October 2021 (https://www.iss.europa. eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/Brief_22_2021_0.pdf).

9. Meissner, K., ‘How to sanction international wrongdoing? The design of EU restrictive measures’, Review of International Organisations, February 2022.

10. Council of the EU, ‘Council Decision (CFSP) 2021/1277 of 30 July 2021 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Lebanon’, OJ L 277I, 2 August 2021, pp. 16–23.

11. Council of the EU, ‘Council Decision (CFSP) 2021/1826 of 18 October 2021 amending Decision (CFSP) 2015/1763 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Burundi’, OJ L 369, 19 October 2021, p.15.

12. Council of the EU, ‘Council Decision (CFSP) 2022/24 of 10 January 2022 amending Decision (CFSP) 2019/1720 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Nicaragua’, OJ L 5I, 10 January 2022, pp. 13–20.

13. Council of the EU, ‘Council Decision (CFSP) 2022/243 of 21 February 2022 amending Decision 2013/184/CFSP concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Myanmar/Burma’, OJ L 40, 21 February 2022, pp. 28–39; Council of the European Union, ‘Council Decision (CFSP) 2021/1965 of 11 November 2021 amending Decision (CFSP) 2017/2074 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Venezuela’, OJ L 400, 12 November 2021, pp. 148–156.

14. Council of the European Union, ‘Council Decision (CFSP) 2022/218 of 17 February 2022 amending Decision 2012/642/CFSP concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Belarus’, OJ L 37, 18 February 2022, pp. 41–45.

15. Council of the European Union, ‘Council Decision (CFSP) 2021/855 of 27 May 2021 amending Decision 2013/255/CFSP concerning restrictive measures against Syria’, OJ L 188, 28 May 2021, pp. 90–99.

16. Portela, C., ‘The EU sanctions operation in Syria: Conflict management by other means’, UNISCI Journal, Vol. 23, No 1, 2012, pp. 151-158.

17. Portela, C. and Meissner, K., ‘The European approach to multilateral sanctions’, in Charron, A. and Portela, C. (eds.), Multilateral Sanctions Revisited, McGill University Press, Montreal, 2022, pp. 81-98.

18. Doxey, M., ‘Sanctions Through the Looking Glass: The Spectrum of Goals and Achievements’, International Journal, Vol. 55, No 2, 2000, pp.207-223.

19. Fisher, J., ‘Does it Work?’ – Work for whom? Britain and Political Conditionality since the Cold War’, World Development, Vol. 75, November 2015, pp.13-25 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/ S0305750X14004033).

20. Wilson, W., Address at the Coliseum at the State Fair Grounds, Indianapolis, 4 September 1919.

21. Cortright, D. and Lopez, G., The Sanctions Decade, Lynne Rienner, Boulder, Co., 2000.

22. Kirkham, E. and Flew, C., ‘Strengthening embargoes and enhancing human security’, Biting the bullet Briefing No 17, University of Bradford, Bradford, 2003.

23. Meister, S., ‘Sierra Leone’ in Boulden, J. (ed.), Responding to Conflict in Africa, Palgrave, Houndmills, 2013, pp. 231-256.

24. Wallensteen, P. and Grusell, H., ‘Targeting the Right Targets? The UN Use of Individual Sanctions’, Global Governance, Vol. 18, No 2, 2012, pp. 207–230.

25. Cited in Portela, C. and Van Laer, T., ‘The design and impact of individual sanctions: Evidence from elites in Côte d’Ivoire and Zimbabwe’, Politics and Governance, Vol. 10, No 1, 2022, pp. 26–35.

26. Portela, C. and Romanet-Perroux, J.L., ‘Mediation and sanctions in Libya: Synergy or obstruction?’, Global Governance, Vol. 28, No 2, 2022.

27. Lektzian, D. and Souva, M., ‘An institutional theory of sanctions onset and success’, Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 51, No 6, 2007, pp. 848- 871.

28. Licht, A., ‘Hazards or hassles? The effect of sanctions on leader survival’,Political Science Research and Methods, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2017, pp.143-161.

29. Escribà-Folch, A., ‘Los regímenes no democráticos’, in Barreda, M. and Ruiz, L. (eds.), Análisis de la Política, 2016, Huygens, Barcelona, pp. 121- 140.

30. Escribà-Folch, A. and Wright, J., ‘Dealing with tyranny. International sanctions and the survival of authoritarian rulers’, International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 54, No 2, 2010, pp. 335-359.

31. Brooks, R., ‘Sanctions and regime type: What works, and when’, Security Studies, Vol. 11, No 4, 2002, pp. 1-50.

32. Sejersen, M., Severing the lifelines of tyranny: How individually targeted sanctions can decrease public, elite, and international support for autocratic regimes, Politica, Aarhus, 2019 (https://politica.dk/fileadmin/politica/ Dokumenter/Afhandlinger/mikkel_sejersen.pdf).

33. Biersteker, T., Eckert, S. and Tourinho, M., Targeted Sanctions: The effectiveness of UN action, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2016.

34. Portela, C., ‘Are EU sanctions “targeted”?’, Cambridge Review of International Affairs, Vol. 29, No 3, 2016, pp. 912-29.

35. De Vries, A., Portela, C. and Guijarro, B., ‘Improving the effectiveness of sanctions: A checklist for the EU’, CEPS Special Report 95, CEPS, Brussels, 2014.

36. Hovi, J., Huseby, R. and Sprinz, D., ‘When do (imposed) economic sanctions work?’, World Politics, Vol. 57, No. 4, 2005, pp. 479-99.

37. ‘The design and impact of individual sanctions: Evidence from elites in Côte d’Ivoire and Zimbabwe’, op.cit., p.31.

38. Portela, C., European Union Sanctions and Foreign Policy, Routledge, Abingdon, 2010.

39. Bultrini, A., ‘EU Sanctions and Russian manoeuvring: Why Brussels needs to stay its course while shifting gears’, IAI Commentaries 20/46, June 2020 (https://www.iai.it/en/pubblicazioni/eu-sanctions-and- russian-manoeuvring-why-brussels-needs-stay-its-course-while- shifting).

40. European Union Sanctions and Foreign Policy, op.cit.

41. Hernández Sierra, A., ‘Sanciones europeas: Mitos y realidades’, Política Exterior No. 206, 2022.

42. Szép, V., ‘Unmatched levels of sanctions coordination: The strength of transatlantic cooperation in the Russia’s war on Ukraine’, VerfBlog, March 2022 (https://verfassungsblog.de/unmatched-levels-of- sanctions-coordination/).

43. Helwig, N. and Pesu, M., ‘EU decision-making in sanctions regimes’, in Helwig, N., Jokela, J. and Portela, C. (eds.), Sharpening EU sanctions policy, FIIA Report 63, FIIA, Helsinki, 2020, pp. 85-104.

44. European Commission, ‘Freeze and Seize Task Force: Almost €30 billion of assets of Russian and Belarussian oligarchs and entities frozen by the EU so far’, Press Release IP/22/2373, Brussels, 8 April 2022.