You are here

Creativity wanted: Countering the extraterritorial effects of US sanctions

Introduction

Scarcely familiar with sanctions as a policy tool, much of the European public has followed the headlines about international sanctions with some puzzlement. After the UN lifted sanctions on Iran following the conclusion of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), why was it necessary to create a channel for bilateral trade, the Instrument in Support of Trade Exchanges (INSTEX), following the US withdrawal from the deal in 2018? Why is Iran insisting that the US lift sanctions ‘in practice, not verbally or on paper’ (1)? How did the US Senate approval of new legislation targeting Nord Stream 2, a pipeline under construction between Russia and Germany, bring work to an immediate standstill in late 2019 (2)? Why do European banks and private companies fear the US Department of the Treasury’s sanctions enforcement agency, the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) (3)? If sanctions regimes are endowed with humanitarian exemptions, why do humanitarian agencies report difficulties in getting aid to places like Syria (4)? As it turns out, these are ramifications of the same phenomenon: the extraterritorial effects of US sanctions. The present Brief examines these effects, describing why they pose a challenge to the EU. It then outlines the responses that have been activated or are being contemplated to counter them, explaining why an effective remedy remains elusive. The Brief concludes by indicating possible ways forward.

Secondary sanctions, extraterritorial effects and over complicance

Although ‘secondary sanctions’ and ‘extraterritorial effects’ are often lumped together, these terms have different meanings. Unlike primary sanctions, secondary sanctions target non-US individuals and entities that engage in transactions involving a US sanctions target. However, already US primary sanctions can display extraterritorial effects by virtue of Washington’s extensive interpretation of its jurisdiction: instead of determining their applicability by country of incorporation, US sanctions legislation extends to all US entities, including overseas branches and subsidiaries. Significant extraterritorial effects of these unusually broad primary sanctions emanate from the dominance of the US dollar in trade and capital market transactions. Every transaction in US dollars passes through the US financial system, since non-US banks need to use a correspondent account with a US bank. Given that US banks are required to observe US sanctions regulations, these affect transactions between non-US banks located overseas. Foreign firms do not need to be fined to be deterred from disobeying US bans: as soon as they feature on a US blacklist, banks will refuse to transact with them, rendering business impracticable (5).

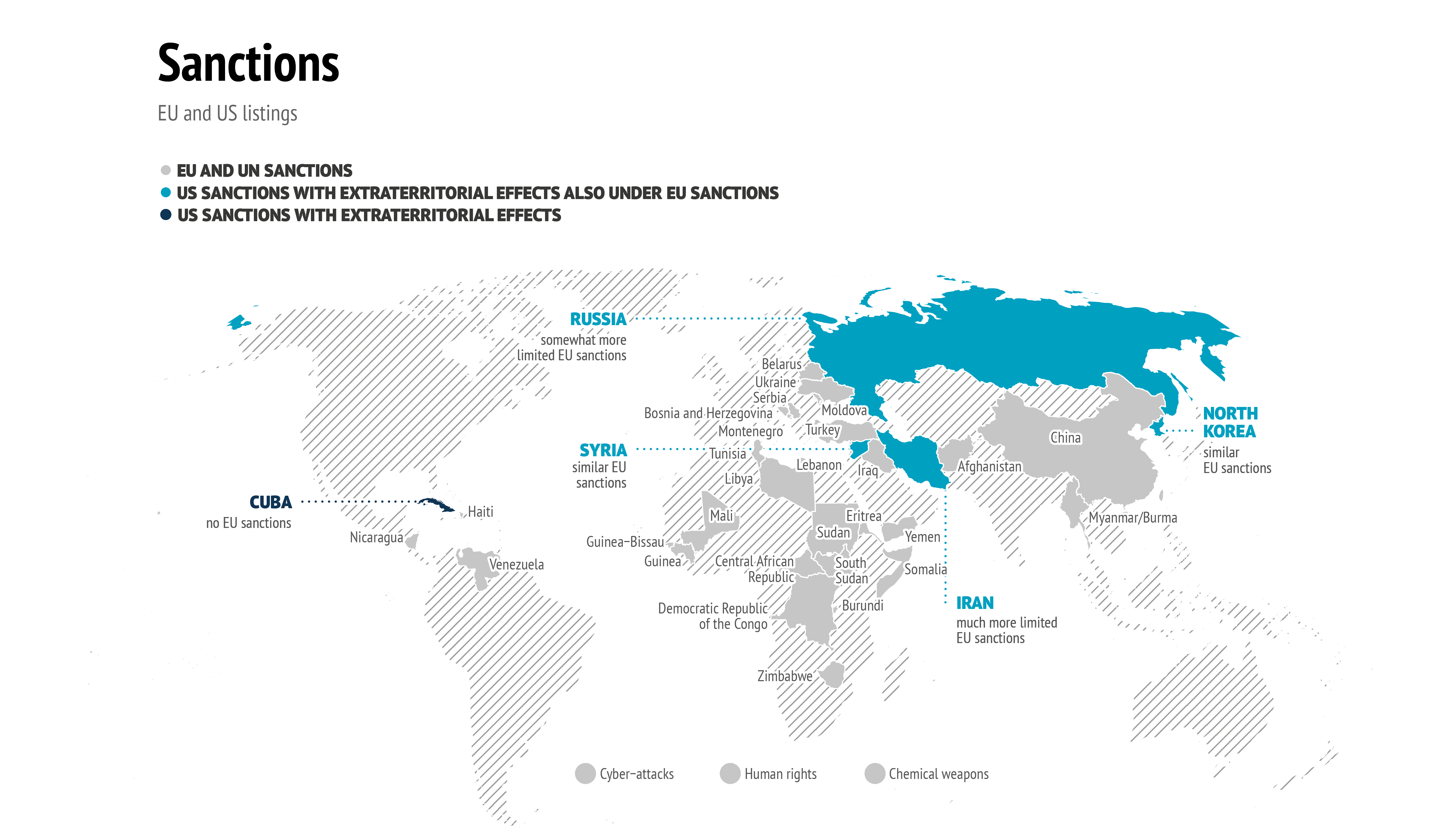

The extraterritorial application of sanctions, both primary and secondary, has a major impact on Europe, as it causes US sanctions to prevail over domestic European law. Far from being a merely economic issue, the extraterritorial effects of US sanctions constitute a geopolitical challenge. The EU is directly affected by the extraterritorial effects of US sanctions against third countries like Iran, Russia or Cuba (6). Secondary sanctions are used to exert influence on EU firms: they punish European entities which engage in dealings with third states under Washington’s sanctions. Even though these restrictions are not embraced by the EU, European firms are compelled to observe them, or ‘over-comply’ (7). This particularly applies to banks, which need access to the US financial market in order to conduct dollar-denominated operations.

This does not only entail that European firms forego business opportunities in markets which, like Iran, are in theory available to them. The withdrawal of European companies from Iran happens at a cost to the foreign policy objectives of the EU, as it reduces the incentives for the Iranian leadership to uphold the JCPOA. To this, one should add the reputational cost of the EU’s diminished authority to regulate the commercial activity of European firms, and of its limited ability to protect them from foreign regulation. These limitations are manifestly at odds with the EU’s ambition to boost what has been labelled as ‘strategic autonomy’.

Tectonic changes under the radar

The extraterritorial application of US sanctions was a matter of contention already in the late 1990s, when US Congress adopted the Helms-Burton Act (short for ‘Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act’), eliciting a transatlantic crisis. This legislation allows US citizens with claims to property expropriated by Cuban authorities to sue foreign companies and individuals exploiting such property. Their executives and shareholders, as well as their immediate families, are denied entry to US territory. By means of the enactment of a ‘Blocking Statute’, Brussels prohibited European firms from complying with US measures, (8) and threatened Washington with bringing a case to the World Trade Organisation (WTO). Tensions were eventually resolved thanks to then-President Clinton’s issuance of a waiver exempting European companies.

The extraterritorial effects of US sanctions constitute a geopolitical challenge for the EU.

After the resolution of the crisis, alterations took place in US sanctions design and enforcement which were to have lasting impacts. Firstly, Washington started to rely increasingly on financial sanctions to pressure Iran into abandoning proliferation-sensitive practices. The architects of sanctions saw themselves operating in a context in which international cooperation was not forthcoming, neither from a divided UN Security Council, nor from European partners lacking a tradition of forceful sanctions imposition. Washington’s awareness that cooperation would be limited compelled it to design sanctions (9) that did not require a UN seal or much international cooperation to be impactful. Secondly, OFAC changed both its targets and its enforcement tactics: instead of picking on small firms transacting with Cuba, OFAC aimed at banks responsible for egregious breaches particularly of the Iran sanctions, and diversified its action to cover firms operating in a broader range of sectors. The transformation of US sanctions enforcement was enabled by new legislation: The 2007 International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) removed ceilings for penalties and allowed fines for different breaches to accumulate. OFAC targeted banks for several violations, and imposed multiple penalties that accumulated in large amounts. This resulted in unprecedented fines that caused a commotion across the Atlantic (10).

As part of this tactical change, OFAC started to pay special attention to foreign entities (11). The percentage of OFAC enforcement actions against foreign firms and banks rose steadily: from 4 % under President Bush to 19 % under Obama to 43 % in the first years of the Trump administration (12). Interestingly, the medical and pharmaceutical sector have not been spared from enforcement actions, which helps explain why humanitarian exemptions fail to work as planned. Indeed, despite the presence of humanitarian exemptions in all EU sanctions regimes, humanitarian action is hampered by sanctions (13). This evolution was facilitated by the autonomous operation of the financial system, which endeavours to avoid risks and uncertainty with the help of security technologies which discourage transactions with entities under US sanctions (14). The use of automated screening technologies exacerbates the extraterritorial effects of US sanctions, as they typically flag any business activity with Cuba, Iran, North Korea, Syria and the Crimean region as inadvisable (15). As a result, transactions that are permissible from a regulatory point of view are routinely rejected by the banks (16).

However, it was not until the US withdrawal from the JCPOA in May 2018 and its re-imposition of sanctions on Tehran that European authorities realised the magnitude of OFAC’s influence on operators (17). They soon found that there was little they could do to prevent their firms from disengaging from Iran. In reality, the Obama administration had already made ample use of secondary sanctions against Tehran (18). However, the extraterritorial effects of sanctions were not visible at the time because US and EU policies largely aligned (19). As the transatlantic approaches diverged under the Trump administration, the use of economic coercion revealed European vulnerability to Washington’s ‘weaponisation of interdependence’ (20). Once convergence collapsed, European authorities found humanitarian actors banging at their doors, protesting that banks refused transactions to enable relief efforts (21).

Framing European responses

Following Washington’s re-imposition of unilateral sanctions on Iran, Brussels responded to their extraterritorial effects by reactivating the dormant Blocking Statute of 1996 (22). The resort to this legislation was straightforward as the tightening of US sanctions on Iran was followed by the expiry of the waiver exempting EU firms from the effects of the Helms-Burton Act, which penalises companies conducting business with Cuba. Since the Blocking Statute was never derogated, the Commission could merely add US sanctions against Iran to its annex. With this move, Brussels delivered an unequivocal signal of rebuff to the extraterritorial application of sanctions. However, since the legislation makes it illegal for European companies to comply with US sanctions, these face a precarious choice between disobeying US regulation, risking fines and exclusion from the US market, or breaching EU law. The Blocking Statute has been criticised for offloading the transatlantic dispute to firms, placing them ‘between a rock and a hard place’ (23).

The use of economic coercion revealed European vulnerability to Washington’s ‘weaponisation of interdependence’.

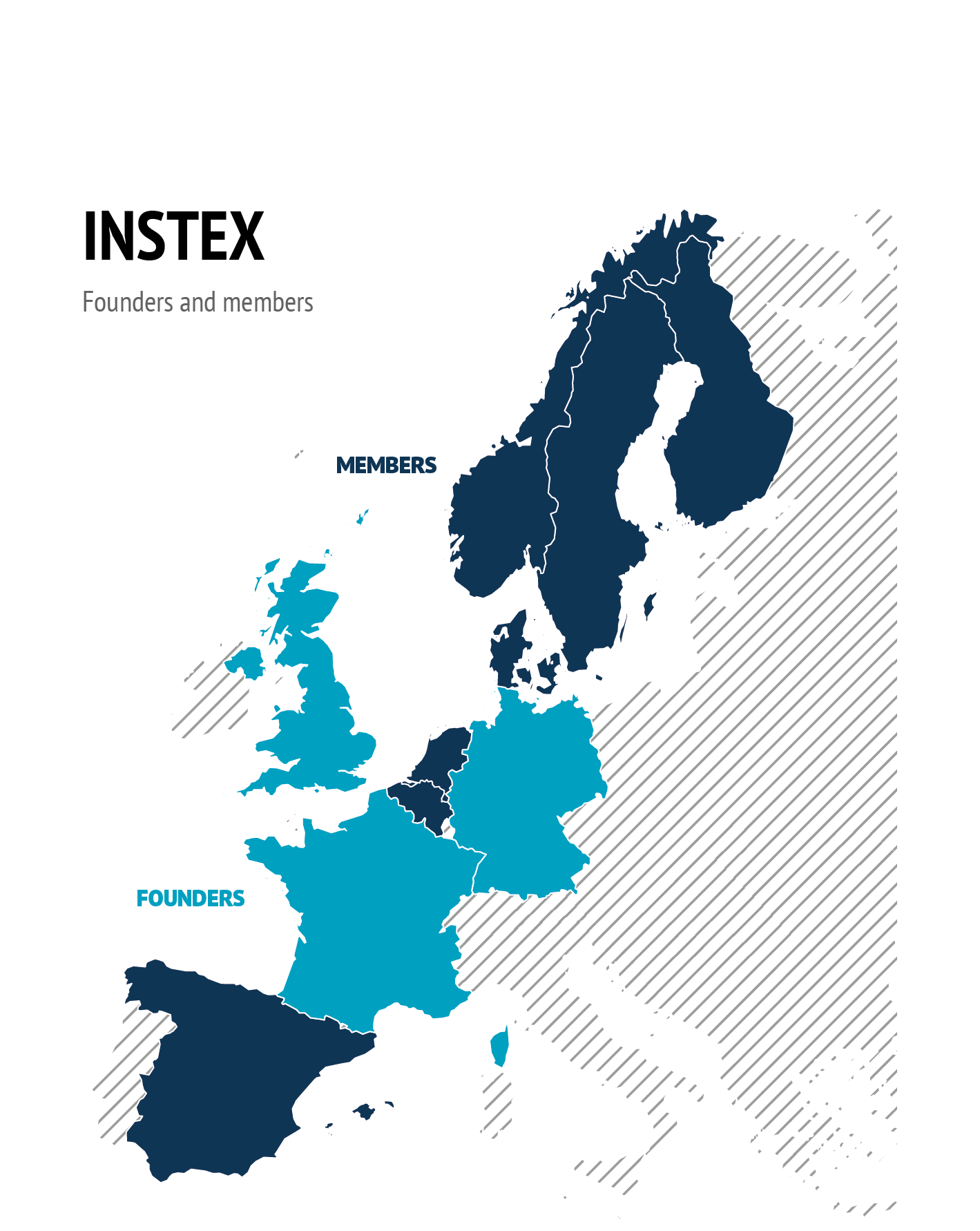

A second response was formulated, strictly speaking, outside the EU context. As signatories of the JCPOA, France, Germany and the United Kingdom created a channel for transactions with Iran, INSTEX (24). In 2019, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands and Sweden became shareholders, alongside non-EU member Norway (25), later joined by Spain. However, INSTEX did not process its first transaction until March 2020, facilitating the export of medical goods after Iran had been hit by the Covid-19 pandemic (26). The modest effectiveness of INSTEX is largely due to private sector reluctance to been seen in breach of US sanctions so as to retain access to the US market and avoid fines by OFAC (27), a particularly acute danger following the US threat to sanction anyone using the channel (28). As a result, the volume of trade between the EU and Iran declined significantly despite the availability of a dedicated channel. This has caused tensions with the Iranian leadership, which has put into question European commitment to re-launch commercial exchange.

A recent initiative emanates from the mandate issued in late 2019 by the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, who exhorted Vice-President Valdis Dombrovskis ‘to develop proposals to ensure Europe is more resilient to extraterritorial sanctions by third countries’ in order ‘to support our economic sovereignty’ (29). It took the shape of the Commission Communication from January 2021 titled ‘The European economic and financial system: fostering openness, strength and resilience’, which proposed a set of measures to strengthen the role of euro as a global currency (30).

A modest reaction gaining momentum

Overall, European responses are manifestly insufficient, both in terms of their efficacy in mitigating the extraterritorial effects of US bans and the message of EU cohesion they convey to third actors. The Blocking Statute, originally designed with the Helms-Burton legislation in mind, is not entirely suited as a response to other types of secondary sanctions. The message of unity sent by the inclusion of US sanctions against Iran in the annex of the Blocking Statute is not matched by the addition of secondary sanctions regarding Russia. The fact that not every set of sanctions with extraterritorial effects is automatically inserted in the annex – at least those lacking an EU equivalent – fails to convey a signal of unity. For its part, INSTEX has the merit of embodying the Franco-German partners’ continued cooperation with the United Kingdom after its withdrawal from the EU, which augurs well for future sanctions coalition-building. However, two years after the formal establishment of the body, only eight of the 27 EU members have joined. Yet, the modest potential of these tools to counter the extraterritorial effects of US bans was anticipated. As recognised by Pierre Vimont, former Secretary-General of the European External Action Service (EEAS), ‘INSTEX was never thought of as economically efficient’ but rather as ‘a political answer to underline to Iran that we, like Russia and China, are still committed to the nuclear deal’ (31). Similarly, Vice-President Dombrovskis acknowledged that the Blocking Statute would be of ‘limited’ use given the global reach of finance (32).

As for the 2021 communication on resilience, initiatives designed to bolster the euro will take time to bear fruit, and have the potential for solidifying resilience only in the mid-to long term. Ironically, unilateral US sanctions have already enhanced the popularity of the euro as a currency for energy trade as companies in countries under sanctions have moved to denominate their export contracts in euro to de-link their business from the US-centred financial system (33). What is probably most intriguing about the communication is its emphasis on the implementation and enforcement of EU sanctions, an issue seemingly unrelated to the extraterritorial effects of third-party sanctions.

While the communication foregrounds the euro, the document conspicuously features a section on the strengthening of the implementation and enforcement of EU sanctions that foresees a central role for the European Commission. While the Commission has not explained the mingling of both issues, it might be inferred that the underlying rationale is that enhancing the EU’s credibility in implementation and enforcement may help it to fend off external scrutiny, at least when it comes to the EU’s own restrictions. A new drive to ensure uniform enforcement of sanctions despite the decentralised system that prevails in the EU (34) might have combined with a desire to improve a reputation for enforcement. Brussels might be compelled to highlight its commitment to implementation and enforcement matters after Ukrainian President Zelensky’s comments about Europeans ‘not enforcing the sanctions’ against Russia in his infamous phone conversation with President Trump of July 2019, (35) or US admonishments to Madrid for continued dealings with blacklisted Venezuelan leaders (36).

Alternative remedies under scrutiny

In view of the deficiencies of existing responses, fresh ideas have been floated. A first set of proposals comprises legal and financial tools to reduce the vulnerability of European companies to the extraterritorial application of sanctions. This includes reforming the Blocking Statute, strengthening the global role of the euro, setting up a compensation fund for companies and establishing a bank of foreign trade as well as an European equivalent to OFAC (37). A second set rests on the notion of attaching a ‘price tag’ to US extraterritorial measures (38). In contrast to the first set, these would be retorsions of temporary application. This entails the restriction of access to banking activities in Europe, to participation in public procurement, the imposition of tariffs and other measures authorised by art. XXI GATT, and restrictions on admission of responsible decision-makers into European territory.

Ironically, unilateral US sanctions have already enhanced the popularity of the euro as a currency for energy trade.

Many of these ideas are already finding reflection in recent initiatives. The European Commission is currently preparing a new legal tool – an ‘anti-coercion instrument’ - to counteract coercive practices by third countries, which is meant to empower the Commission to apply trade and investment restrictions. This rests on a joint declaration by the Commission, the Council and the European Parliament from February 2021, which announced that it ‘would allow the expeditious adoption of countermeasures triggered by such actions’ (39). Similarly, in a recent follow-up to the January 2021 Communication, the Commission outlined options for the reform of the Blocking Statute with a view to upgrading its effectiveness and simplifying compliance (40). Among other provisions, it proposes to provide the Commission with powers to adopt commercial measures against third countries unlawfully applying extraterritorial sanctions, or persons benefiting from their imposition, and restricting their access to EU capital markets and public tenders. In turn, it envisages awarding financial support to EU operators willing to engage in trade impeded by the extraterritorial effects of foreign sanctions.

Data: European Commission, 2021

Finally, the question of the ideal institutional locus for coordinating and managing the response to extraterritorial effects remains. From the outset, responsibility for managing the Blocking Statute was entrusted to the Commission’s sanctions unit. This is ironic given that their main mission involves the opposite role: drafting sanctions legislation and implementation oversight. Once the EU moves to articulate a broader, more multifaceted response, the unit might prove inadequate. Then again, establishing an equivalent to the US Treasury’s OFAC is not feasible, as it would involve concentrating competences that are currently spread between the EU and the Member State level, and would necessitate a major overhaul (41). Proposals for a ‘resilience office’ sit equally uncomfortably with the EU’s current institutional setting: the framing of a comprehensive response to extraterritorial effects will require instruments, competences and skills in the hands of the Commission as well as of the EEAS – already a hybrid body.

A way ahead

The developments that led to the global reach of US sanctions demonstrate a highly sophisticated approach, cleverly designed by its architects. Probably the most remarkable of its effects is the fact that, by affecting the calculations of the private sector, extraterritorial effects cannot easily be reversed by European authorities. Resorting to the Blocking Statute forces European firms to make commercially difficult choices. While some of the remedies under consideration appear viable, if not promising, they are not without difficulty. Some of them, like the strengthening of the euro, will take years to bear fruit, and do not provide an immediate fix to current woes. Others involve a rather confrontational approach, departing from the amicable tone characterising European ties with the US. Even if they prove effective, they may come at a political cost to the transatlantic relationship. Whichever formula is eventually selected, some simple but useful steps can be implemented without much controversy.

Resorting to the Blocking Statute forces European firms to make commercially difficult choices.

Flagging the response to extraterritorial effects of sanctions as a priority

A first and fundamental step consists in a recognition that the extraterritorial reach of US unilateral sanctions is a common European problem, rather than one concerning individual Member States which are unevenly affected depending on their level of trade with US targets. Only the acknowledgement of an all-EU interest in countering extraterritorial effects will allow for the mobilisation of institutional resources and the investment of the political capital necessary for framing an effective response.

Internally, this entails the generation of reliable and accurate data on the losses to the European economy due to the extraterritorial effects of third-country unilateral sanctions. While this data could be obtained from Member State sources, it should be calculated according to a common methodology in the interest of uniformity, and be made available to both institutions and Member States. Yet, economic losses are not the only costs associated with the extraterritorial application of sanctions – reputational losses ought to be factored in as well. Externally, in the same way that the adoption of EU sanctions delivers a message of unity to third actors, the response to the extraterritorial application ought to be common. Third parties attempting to apply sanctions legislation extraterritorially will take a united EU front more seriously than bilateral complaints by individual capitals.

Re-engaging Washington beyond the Oval Office

A second set of actions should be geared towards the US. Capitalising on the Biden administration’s openness to cementing longstanding partnerships, the EU could launch a diplomatic campaign leading to the issuance of waivers, along the lines of that granted by US President Biden for the completion of Nord Stream 2 (42). To help the current administration persuade reluctant players, Brussels could offer to step up its cooperation on thematic or geographic sanctions regimes where the EU can align with Washington (43). The review of sanctions policy performed by the US administration offers an opportune moment for raising this topic on the transatlantic agenda (44).

Meanwhile, the EU should complement its government-to-government approach with a broader effort to engage US actors. Priority should be given to Congress, the key originator of sanctions legislation. Additionally, it should reach out to key decision-makers across the political spectrum, including at the sub-federal level, as well as influential civil society players like interest groups, with a view to strengthening domestic support for cooperative approaches with like-minded partners in sanctions matters. Ties to actors with the strongest interest in consolidating ties with traditional allies should be cultivated with particular dedication.

Another approach would be to challenge the extraterritorial effects of sanctions before US courts.(45) According to this proposal, the US administration’s expansive interpretation of its enforcement jurisdiction in domestic courts is a promising avenue, in light of the narrower concept prevailing with the US Supreme Court. The EU could encourage and assist European companies to challenge the extraterritorial enforcement of US sanctions in its own judicial system. This avenue would have the effect of bringing the issue ‘back’ to the domestic terrain of the US, rather than framing it as an international dispute.

Supporting and scrutinising firms' compliance with European sanctions

EU and Member State authorities should make every effort to help European firms observe European sanctions. Due to the traditionally modest nature of EU sanctions, and the predominance of small and medium-sized enterprises in Europe, many companies require guidance to optimise compliance. Obtaining more support from relevant authorities will help them improve compliance and establish positive mutual relationships. In parallel, a closer supervision of national authorities by the Commission could accompany the scrutiny of firms by national agencies. Whether this will eventually translate into a less intense monitoring of national enforcement agencies by OFAC and a less frequent targeting of European firms is uncertain. However, by improving the implementation and enforcement of sanctions, the EU will be better protected from accusations of deficient implementation – or evasion – that catch media attention and tarnish its reputation.

Forging partnerships with other affected jurisdictions

In order to limit the extraterritorial reach of US measures, an effort should be made to liaise with like-minded partners which, like Canada and the United Kingdom, are also affected by the extraterritorial application of US sanctions (46). Other than sharing experiences and improving practices related to the application of their respective Blocking Statutes, they could show uniform opposition to the legality of extraterritorial sanctions legislation in international forums. In the event that the re-engagement with Washington fails to bear the desired results, more forceful responses could be framed alongside affected partners.

The EU should complement its government-to-government approach with a broader effort to engage US actors.

Improving internal foresight

Internally, Brussels should acknowledge a failure in anticipation, and prepare better for future developments in geo-economics. The impacts of the extraterritorial application of US sanctions caused dismay in Europe because a number of important alterations in Washington’s policy had been unfolding ‘under the radar’. While convergence on the Iranian dossier was forthcoming, it was not anticipated that Washington’s reapplication of sanctions would stop European trade with Iran, evidencing a failure of foresight. The foresight process currently underway in the Commission should entail a reflection on what the future of economic coercion could look like, anticipating new modalities of coercion and building scenarios for their emergence and mitigation. The EU should ensure that the ‘next incarnation of economic coercion’, in whatever form it comes, should not catch it off guard.

Data: www.sanctionsmap.eu, 2021; European Commission, 2021

Crafting a public diplomacy concept for international sanctions

The EU ought to firmly embed its position on sanctions in its public diplomacy strategy. Washington sees no international legal limitations to the reach of its measures. By contrast, many developing countries view all unilateral sanctions as illicit. Russia and China vocally oppose the imposition of sanctions as contrary to international law, claiming that unilateral sanctions supplementing those adopted by the UN Security Council ‘can defeat the … purposes of measures imposed by the Security Council, and undermine their integrity and effectiveness’ (47). The European position diverges from both extremes: Brussels believes that the use of unilateral sanctions conforms to international law but feels that measures should be designed to minimise harm to populations and protect humanitarian action. The specifics and motivation of this view are not self-evident to the global – not even European – public. The need to justify and propagate the case for the use of sanctions à la EU is all the more acute as contestation of sanctions deepens and global powers grow increasingly combative. This is not only visible in Moscow’s wielding of counter-sanctions on perishables after the bans that followed the annexation of Crimea, but also in Beijing’s recent adoption of measures contesting Western sanctions (48).

The EU ought to firmly embed its position on sanctions in its public diplomacy strategy.

To win hearts and minds, the EU ought to assertively oppose the extraterritorial application of sanctions while defending the employment of sanctions within its common foreign and security policy (CFSP), (49) explain their rationale and, jointly with like-minded partners, make the case for the legitimacy of its own approach.

References

* The author would like to thank participants in the EUISS workshop ‘Building resilience against the extraterritorial effects of US sanctions’, held in Brussels on 9 March 2020, for their valuable input in the discussion. Special thanks go to Mr Anthonius de Vries for his comments on earlier drafts.

(1) Ayatollah Khamenei quoted in France24, ‘In Iran standoff, Biden says US won’t unilaterally lift sanctions’, 7 February 2021 (https://www.france24.com/ en/live-news/20210207-in-iran-standoff-biden-says-us-won-t-unilaterally- lift-sanctions).

(2) Rettman, A., ‘US halts building of Russia-Germany pipeline’, EUObserver, 21 December 2019 (https://euobserver.com/foreign/146996).

(3) Fontanelli, G., ‘Così la tagliola delle nuove sanzioni USA contro l’Iran può chiudersi sulle imprese italiane’, Panorama, 24 May 2018.

(4) Debarre, A., ‘Safeguarding humanitarian action in sanctions regimes’, International Peace Institute, New York, 2019 (https://www.ipinst. org/2019/06/safeguarding-humanitarian-action-in-sanctions-regimes).

(5) Servettaz, E., ‘A sanctions primer. What happens to the targeted?’, World Affairs, Vol. 177, No. 2, 2014, pp. 84-89.

(6) Sinkkonen, V., ‘The United States in the Trump era’, in Helwig, N. et al (eds), Sharpening EU Sanctions Policy, FIIA, Helsinki, 2020, pp. 53-68.

(7) Portela, C., ‘How the EU learned to love sanctions’, in Leonard, M. (ed.), Connectivity Wars, European Council on Foreign Relations, London, 2016, pp. 36-42.

(8) Council Regulation (EC) No 2271/96 protecting against the effects of extra- territorial application of legislation adopted by a third country, and actions based thereon or resulting therefrom, OJ L 309, 29 November 1996 (https://eur- lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018R1100&from=EN).

(9) Nephew, R., The Art of Sanctions: A view from the field, Columbia University Press, New York, 2018.

(10) The Economist, ‘America’s legal forays against foreign firms vex other countries’, 19 January 2019 (https://www.economist.com/business/2019/01/19/ americas-legal-forays-against-foreign-firms-vex-other-countries).

(11) Ibid.

(12) Early, B. and Preble, K., ‘Going Fishing versus Hunting Whales: Explaining changes in how the US enforces economic sanctions’, Security Studies, Vol. 29, No 2, 2020, pp. 231-267, p. 248.

(13) ‘Safeguarding humanitarian action’, op.cit.

(14) Jäger, M.D., ‘Circumventing Sovereignty: Extraterritorial sanctions leveraging the technologies of the financial system’, Swiss Political Science Review, Vol. 27, No 1, 2021, pp. 180–192 (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/ epdf/10.1111/spsr.12436).

(15) Round, J., Name Screening: A practical guide to computer-based matching and manual elimination of name matches within a sanctions screening environment, 2017.

(16) ‘Circumventing Sovereignty’, op.cit.

(17) Martin, E., La politique de sanctions de l’Union européenne, Ifri, Paris, 2019 (https://www.ifri.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/martin_sanctions_ ue_2019.pdf).

(18) Harrell, P., ‘Trump’s use of sanctions is nothing like Obama’s’, Foreign Policy, 5 October 2019 (https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/10/05/trump-sanctions- iran-venezuela-russia-north-korea-different-obamas/).

(19) Lohmann, S., ‘The convergence of transatlantic sanctions policy against Iran’, Cambridge Review of International Affairs, Vol. 29, No. 3, pp. 930-951; Portela, C., ‘The triumph of teamwork’, Peace Policy Newsletter, No 23, Kroc Institute, University of Notre Dame, 2017.

(20) Abdelal, R. and Bros, A., ‘Sanctions and the end of Trans-Atlanticism’, Ifri, Paris, 2020 (https://www.ifri.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/abdelal_bros_ sanctions_trans-atlanticism_2020.pdf).

(21) Mallard, G. et al., ‘The humanitarian gap in the global sanctions regime’, Global Governance, Vol. 26, No 1, 2020, pp. 121–153.

(22) Commission delegated regulation (EU) 2018/1100 of 6 June 2018 amending the Annex to the Council Regulation (EC) No 2271/96 protecting against the effects of extra-territorial application of legislation adopted by a third country, and actions based thereon or resulting therefrom, OJ L 1999 J/1, 7 August 2018 (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018R110 0&from=EN).

(23) Ruys, T. and Ryngaert, C., ‘Secondary Sanctions: A weapon out of control? The International legality of, and European responses to, US secondary sanctions’, British Yearbook of International Law, 2021.

(24) See INSTEX website at: https://instex-europe.com/about-us/

(25) Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, ‘Joint statement on joining INSTEX by Belgium, Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden’, November 29, 2019 (https://www.government.nl/documents/diplomatic- statements/2019/11/29/joint-statement-on-joining-instex-by-belgium- denmark-finland-the-netherlands-norway-and-sweden).

(26) Brzozowski, A., ‘EU’s INSTEX mechanism facilitates first transaction with pandemic-hit Iran’, Euractiv, 1 April 2020 (https://www.euractiv.com/section/ global-europe/news/eus-instex-mechanism-facilitates-first-transaction-with-pandemic-hit-iran/).

(27) Giumelli, F. and Onderco, M., ‘States, firms, and security: How private actors implement sanctions, lessons learned from the Netherlands’, European Journal of International Security, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2021, pp. 190-209 (https://www. cambridge.org/core/journals/european-journal-of-international-security/ article/states-firms-and-security-how-private-actors-implement-sanctions- lessons-learned-from-the-netherlands/2D74ECCB8252B534F2B36C2375BA8 8F1).

(28) ‘INSTEX mechanism facilitates first transaction’, op.cit.

(29) European Commission, ‘Mission letter to Valdis Dombrovskis, Executive Vice-President-designate for An Economy that Works for People’, Brussels, 10 September 2019 (https://ec.europa.eu/commission/commissioners/ sites/default/files/commissioner_mission_letters/mission-letter-valdis- dombrovskis-2019_en.pdf).

(30) European Commission, ‘The European economic and financial system: fostering openness, strength and resilience’, COM(2021) 32 final, Brussels, 19 January 2021 (https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/210119-economic- financial-system-communication_en).

(31) Erlanger, S., ‘Nuclear deal traps EU between Iran and US’, New York Times, 8 May 2019 (https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/08/world/europe/eu-iran- nuclear-sanctions.html).

(32) Jones, H., ‘EU says block on US sanctions on Iran of limited use for EU banks’, Reuters, 17 May 2018.

(33) ‘Sanctions and the end of Trans-Atlanticism’, op.cit.

(34) Portela, C., ‘Implementation and enforcement’, in Helwig, N. et al. (eds),Sharpening EU Sanctions Policy, FIIA, Helsinki, 2020, pp. 105-11.

(35) White House, ‘Telephone Conversation with President Zelenskyy of Ukraine’, The White House Situation·Room (declassified), Washington, 25 July 2019 (https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/ Unclassified09.2019.pdf).

(36) Bartenstein, B., ‘U.S. considers targeting Spain in latest push against Maduro regime’, Bloomberg, 31 October 2019.

(37) Bérard, M.H., et al., ‘Sanctions extraterritoriales américaines, vous avez dit autonomie stratégique européenne?’, Institut Jacques Delors, Paris, 2021.

(38) Hackenbroich, J., ‘Defending Europe’s Economic Sovereignty: new ways to resist economic coercion’, Policy Brief, ECFR, Berlin, 2020 (https://ecfr.eu/wp-content/uploads/defending_europe_economic_sovereignty_new_ways_ to_resist_economic_coercion.pdf).

(39) Joint Declaration of the Commission, the Council and the European Parliament on an instrument to deter and counteract coercive actions by third countries, OJ C 49/01, 12 February 2021 (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal- content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32021C0212(01)&from=EN).

(40) European Commission, ‘Inception Impact Assessment’, Ref.Ares(2021)4911405, 2 August 2021.

(41) De Vries, A., ‘Enhancing compliance with EU foreign policy sanctions through better and/or new interfaces’, in Lohmann, S. and Vorrath, J. (eds), International Sanctions: Improving Implementing through Better Interface Management, SWP Working Paper, SWP, Berlin, 2021.

(42) DW, ‘Nord Stream 2: Biden says sanctions “counterproductive” to US- European ties’, 26 May 2021 (https://www.dw.com/en/nord-stream-2-biden- says-sanctions-counterproductive-to-us-european-ties/a-57664272).

(43) Portela, C., ‘Transatlantic cooperation on sanctions in Latin America: From convergence to alignment’, in Soare, S. R. (ed.), Turning the Tide – How to rescue transatlantic relations, EUISS, Paris, 2020, pp. 121-36.

(44) Talley, I., ‘Biden to temper U.S. use of sanctions weapons, officials say’, The Wall Street Journal, 5 July 2021.

(45) Lohmann, S., ‘Extraterritorial U.S. sanctions’, SWP Comment No 5, SWP, Berlin, 2019 (https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.18449/2019C05/).

(46)Joint Statement by Federica Mogherini, Chrystia Freeland and Cecilia Malmström on the decision of the United States to further activate Title III of the Helms-Burton (Libertad) Act, 17 April 2019 (https://eeas.europa.eu/ headquarters/headquarters-homepage/61181/joint-statement-federica- mogherinichrystia-freeland-and-cecilia-malmström-decision-united_ko).

(47) Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, Declaration of the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China on the Promotion of International Law, 25 June 2016 (https://www.mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/ news/-/asset_publisher/cKNonkJE02Bw/content/id/2331698).

(48) Chen, Q. and Liu, X., ‘China’s newly passed Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law to bring deterrent effect against Western hegemony’, Global Times, 10 June 2021 (https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202106/1225911.shtml).

(49) Bendiek, A., Ålander, M. and Bochtler, P., ‘CFSP: The capability-expectation gap revisited’, SWP Comment No 58, SWP, Berlin, 2020.