You are here

A blacklist is (almost) born

Introduction

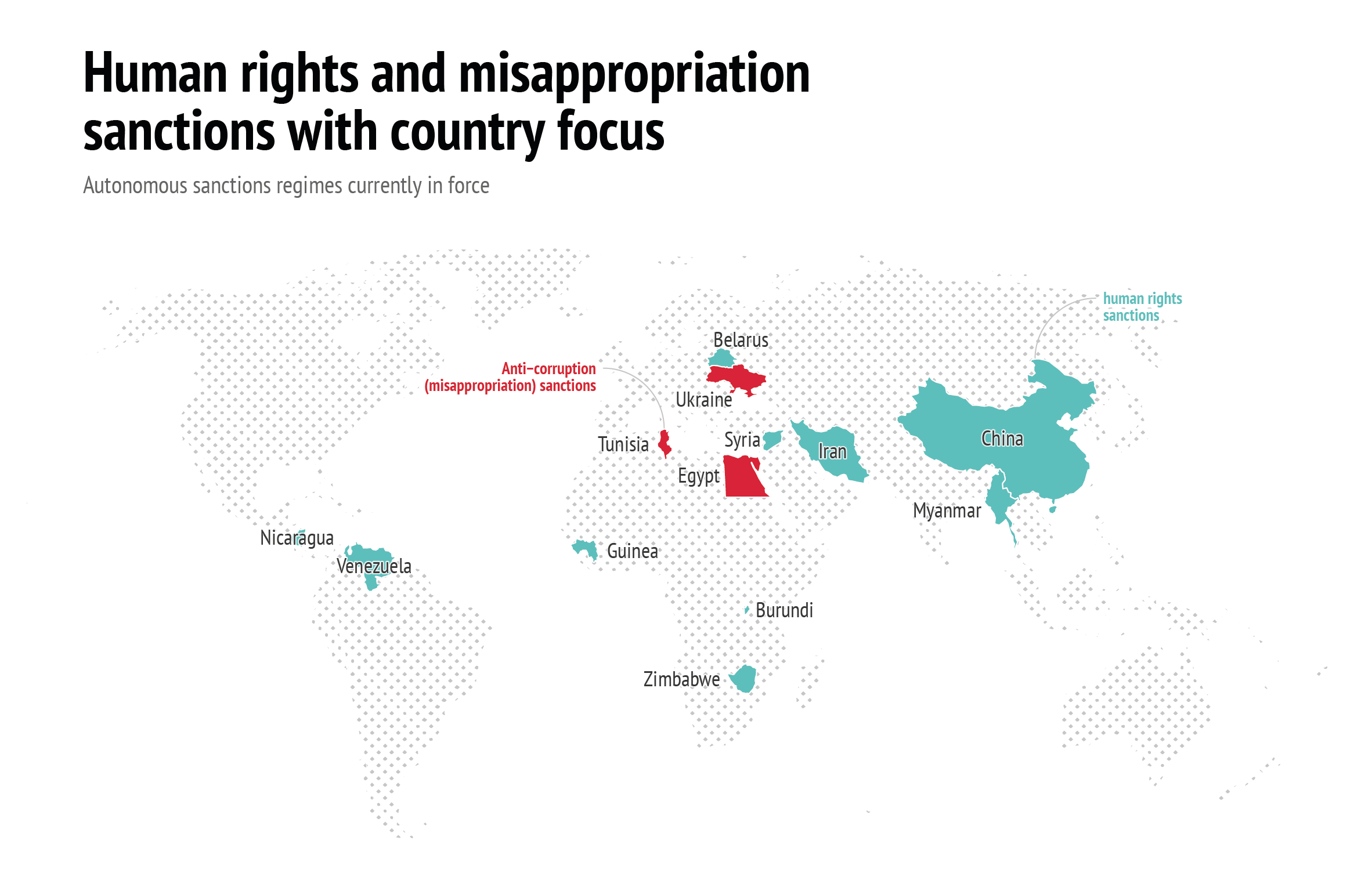

In December 2018, the Council of the European Union initiated discussions about the creation of a new sanctions regime designed to address gross human rights violations, following a proposal from the Netherlands.1 So far, the EU only operates three thematic sanctions regimes: those targeting terrorism, cyberattacks and chemical weapons attacks. Unlike classical sanctions packages addressing crises in specific countries, such as Guinea or Venezuela, horizontal sanctions regimes apply to individuals and entities considered to have committed severe human rights abuses. Once approved, the planned blacklist is set to become the EU’s fourth horizontal sanctions regime, enlarging its vast body of autonomous sanctions regimes, i.e. restrictions adopted in the absence of a United Nations Security Council (UNSC) mandate.2

Over a year after the initial Dutch proposal was tabled, the sanctions regime is still under discussion, which contrasts with the rapid adoption of previous thematic regimes. On first inspection, the slow pace of preparations is puzzling: the vast majority of EU sanctions regimes were traditionally imposed in response to human rights breaches.3 Most EU autonomous sanctions regimes currently in force cite human rights violations as the rationale for their adoption. Indeed, the emphasis on human rights as a key motivation for the imposition of sanctions sets EU autonomous sanctions apart from the practice of other international sanctions senders like the United Nations (UN).4 Given that the promotion of human rights is a centrepiece of EU foreign policy, consensus among member states in support of such a regime should be forthcoming. If human rights breaches constitute the dominant motivation for the imposition of EU autonomous sanctions, what is holding up the approval of the prospective regime? Designing a horizontal sanctions regime in the EU is a much harder task than meets the eye. The present Brief aims to unravel the challenges that make it difficult for this regime to take shape, and suggests ways in which the obstacles identified may be surmounted or, at the very least, mitigated.

Genesis of a blacklist

The idea of creating a horizontal list including perpetrators of grave human rights violations originated in the US. In 2012, Congress passed legislation condemning the torture and death in a Moscow prison of Sergej Magnitsky, a Russian accountant employed with a foreign firm, who had allegedly uncovered a large-scale corruption scheme. The case combined two key elements: human rights violations – mistreatment and death under detention – and grand corruption, as Magnitsky was (again allegedly) detained because of his role as a whistle-blower. The US ‘Magnitsky Act’ blacklisted individuals involved in the episode. This piece of legislation followed a lobbying campaign by Magnitsky’s employer, British businessman Bill Browder. More recently, the US Congress adopted new legislation inspired by the 2012 Magnitsky Act, the ‘Global Magnitsky Act’.5 Rather than being restricted to a specific incident, the new legislation aimed to address gross violations of human rights and corruption on a global scale. This objective effectively removed the geographic and temporal limits that defined the original Magnitsky Act. After being signed into law in 2016 by President Obama, designations were publicised the following year. The first round of listings featured a picturesque mix of thirteen designees of different nationalities spanning from Gambia to Pakistan. Shortly after the adoption of the US Global Magnitsky Act, Canada adopted similar legislation in 2017, labelled the ‘Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials Act’.6

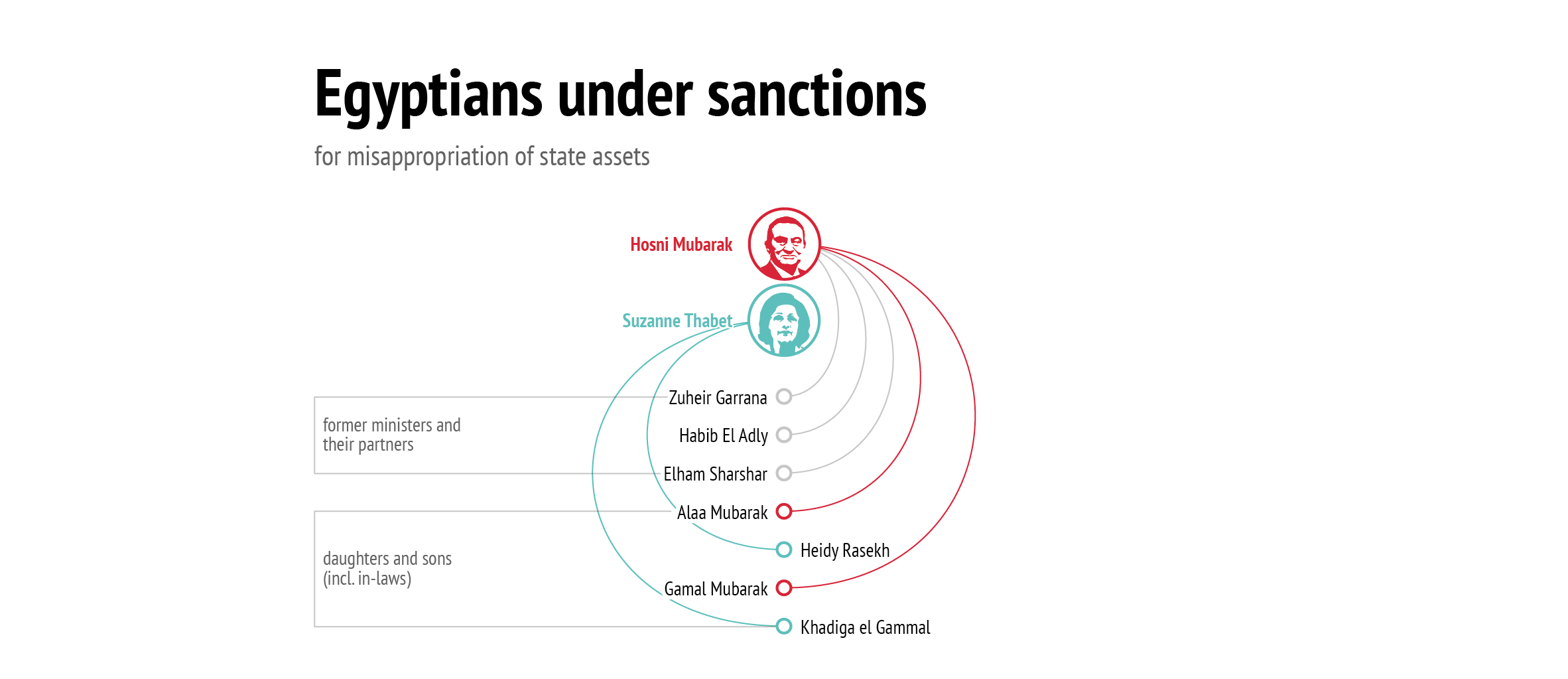

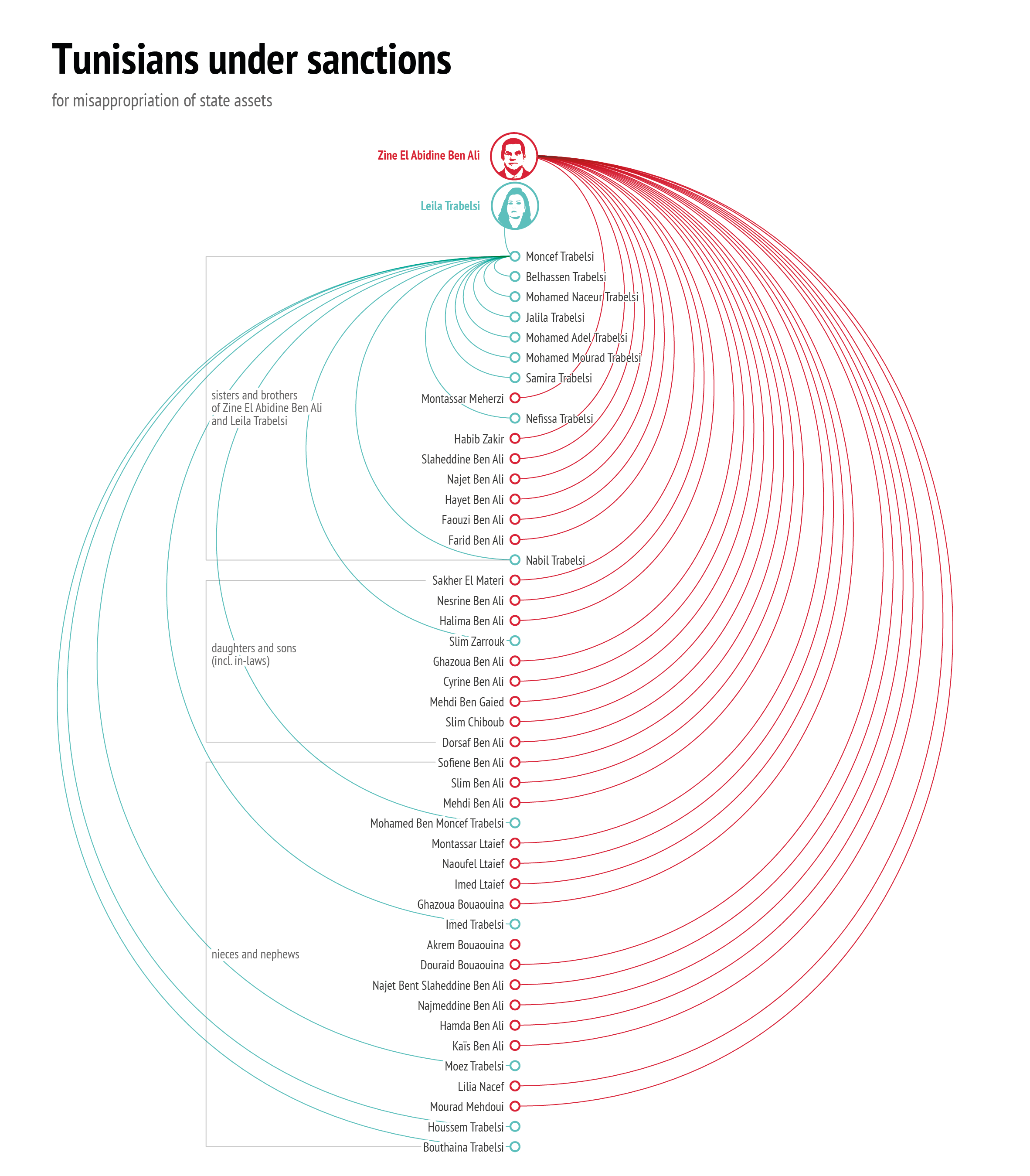

Data: eusanctionsmap.eu,2020; sanctionswatch.cifar.eu, 2020

The first blacklist under this act featured 51 designees from Russia, South Sudan and Venezuela, who were joined by individuals from Burma/Myanmar and Saudi Arabia in subsequent rounds, elevating the number of entries to 70.7 In Europe, the Baltic republics adopted their own versions of the Magnitsky Act in close succession: Estonia in 2016, Lithuania in 2017 and Latvia in 2018.8 However, contrary to Canada, they emulated the original Magnitsky model rather than the global version. The Netherlands officially proposed the establishment of a human rights sanctions regime in November 2018, earning the applause of 90 European civil society organisations dedicated to the promotion of universal human rights and the fight against corruption,9 as well as the endorsement of the European Parliament.10 One year later, EU High Representative Josep Borrell announced the launch of preparations for a ‘horizontal sanctions regime to address serious human rights violations’.11

EU sanctions and human rights

In the sanctions practice of the EU, human rights motivations feature prominently, reflecting the omnipresence of human rights conditionality in its foreign policy.12 Indeed, most sanctions applied by the EU are traditionally geared towards defending human rights.13 EU sanctions policy follows the lead of Washington, the principal sender of human rights sanctions.14 Oftentimes, the breaches the EU protests against via its sanctions concern rights connected to electoral processes, such as the freedom of assembly or freedom of expression. Sanctions usually address situations of democratic backsliding such as those witnessed in Belarus or Zimbabwe over the past decade.15 Thus, the EU’s use of human rights sanctions is closely linked to its policy of democracy promotion, again an agenda shared with Washington.16 By contrast, the sanctions practice of the UN focuses on addressing violent conflict, in implementation of its mandate to maintain international peace, while human rights rarely features as an objective of its sanctions packages.17 Inclusion in blacklists typically entails a ban on entering the territory of the sender, the freezing of bank accounts and property located in its jurisdiction, and a prohibition on blacklisted individuals or entities receiving funds from anyone in the EU. In practice, it also means that companies and especially banks in third countries are often reluctant to transact with those blacklisted.18

Data: eusanctionsmap.eu,2020; sanctionswatch.cifar.eu, 2020

If most EU sanctions are already meant to protect human rights, what is the rationale for creating a thematic sanctions package? Horizontal lists represent the culmination of the notion of targeted sanctions, which are geared to affect only those actors bearing responsibility for the wrongdoing at hand.19 As Canadian expert Kim Nossal pertinently noted, the original US Magnitsky Act listed ‘only 18 out of Russia’s 143 million people’.20 A global human rights list permits more flexibility than a country-based sanctions regime, as it can accommodate multiple nationalities as well as different statuses in relation to the state. This obviates the effort of creating new legislation for the listing of just one or two entries. The mix visible in the 16 first entries of the Global Magnitsky Act illustrates this: some designees are officials from state authorities, others are retired or deposed officials, and yet others are non-state actors such as businesspeople. Subsequent rounds featured the designation of entities alongside individuals.

Transplanting the idea to the EU

While horizontal sanctions regimes are typical of the US rather than of the EU, Brussels has rapidly embraced this practice. Until as recently as 2017, the EU only operated one thematic sanctions regime: the terrorism list. All remaining sanctions regimes were country regimes. To some extent, ‘country regimes’ was already a misnomer, since most of them entailed visa bans and asset freezes on specific elites, rather than measures affecting the country’s economy as a whole. Even those measures that had economic repercussions were intended to penalise elites connected to the violation at the root of the sanctions.21 This started to change in 2018, when the EU adopted a sanctions regime addressing the use of chemical weapons, and shortly after, one directed at perpetrators of cyberattacks. All of these thematic sanctions regimes originated in rather atypical circumstances. The emergence of the anti-terrorism list back at the beginning of the current century responded to an external stimulus: a mandate by the UNSC agreed in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks in New York. Brussels implemented it and added its own entries, thereby giving rise to the EU’s terrorism blacklist. The impulse for the most recent thematic regimes came directly from the European Council, rather than originating in a geographical Council Working Party.22 The EU’s adoption of horizontal lists ensures compatibility with the US sanctions system, while it allows for the blacklisting of Russian targets, precluding the need to create new sanctions regimes based on the presumption that the condemned actions were orchestrated by Moscow.

Until as recently as 2017, the EU only operated one thematic sanctions regime: the terrorism list.

When discussions on a global human rights sanctions regime started, a transition to horizontal sanctions regimes was underway in the EU. Out the 36 sanctions regimes currently in force, only the three abovementioned examples lack any country connection, while 33 are country regimes, either autonomous or supplementary to UN measures.23 However, several sanctions packages feature a thematic focus in addition to a country link, thereby constituting a hybrid type that can be considered a precursor to the recent horizontal regimes. Illustratively, a sanctions regime against Iran linked to proliferation of weapons of mass destruction – currently suspended – co-existed with an active sanctions regime in relation to human rights violations. Similarly, three separate sanctions regimes share a focus on Ukraine: one of them enacted in response to the annexation of Crimea, a second one in respect of actions undermining Ukraine’s territorial integrity, and a third one addressing the misappropriation of state funds.24 Until 2012, listings in relation to the campaign against Latin script schools in Transnistria co-existed with a blacklist of Transnistrian leaders contesting Moldovan sovereignty over the region.25 Thus, the establishment of thematic blacklists fully detached from a geographical area represents a further step towards a greater focus on the condemned actions.

The intricacies of blacklists

In spite of the EU’s robust record as a worldwide advocate of human rights, the adoption of a human rights sanctions regime by Brussels entails major challenges that jeopardise its prospective contribution to the CFSP sanctions acquis. The development of the new sanctions regime is taking place against the background of the judicial scrutiny exercised by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), headquartered in Luxembourg. The most serious challenge to the imposition of sanctions against individuals emerges from the obligation to grant due process guarantees to designees established by the jurisprudence of the Luxembourg court. Its landmark ruling on the Kadi case of 2008, brought by designees featuring on a terrorism blacklist, found Council listings to be in violation of the right to effective judicial remedy. The Kadi ruling inaugurated an era of extensive litigation, with challenges to Council listings soon running into the hundreds.26 Thanks to abundant litigation, case-law has established the requirements for individual listings in terms of the specification of designation criteria, statement of reasons and supporting evidence, all of which had been absent in the early days of blacklisting. In addition to improving its substantiation of reasons and the gathering of evidence in support of its listings, the Council also broadened its listing criteria. EU sanctions regimes traditionally claim to target those who ‘undermine democracy, respect for human rights and the rule of law’. However, the standard criteria governing listings have evolved so that sanctions target ‘those identified as responsible for the policies or actions that have prompted the EU decisions to impose restrictive measures and those benefiting from and supporting such policies and actions’. By broadening the designation criteria, listings have become less vulnerable to legal challenges.

The legal situation sets the EU apart from its North American allies, where blacklists are not subject to comparable levels of judicial review.

Despite these precautions, the problem of legal challenges is far from resolved. Instead, they continue to represent a key preoccupation for the drafters of the prospective regime, which fear the reputational costs resulting from Court annulments of listings.27 The legal situation sets the EU apart from its North American allies, where blacklists are not subject to comparable levels of judicial review. Thus, the designation criteria of a prospective human rights sanctions regime must allow the Council to prepare listings that are sufficiently robust to withstand judicial scrutiny while maintaining due process guarantees in conformity with the high standards set by the CJEU.

The first question obviously concerns who should be targeted for what reason. This inevitably involves defining how extensive the circle of potential designees should be. Broadly formulated designation criteria can lead to the blacklisting of a large number of individuals responsible for gross abuses. However, advocacy by European civil society organisations may lead to a rapid proliferation of designations. Lobbying efforts will be especially hard to resist when they concern perpetrators of solidly-documented abuses. Narrow designation criteria will result in shorter blacklists; however, the concern is that they may be more vulnerable to court challenges, and limit the flexibility of the Council in making designations. Thus, in defining the breadth of the designation criteria, a balance must be struck between resilience to court scrutiny and the potential for listing proliferation.

Beyond litigation woes

A second question concerns the specific human rights breaches to be covered by the regime. The conditionality provisions embedded in the EU’s general system of trade preferences constitute a potential source of inspiration. This scheme threatens to suspend trade privileges for ‘serious and systematic violations of the principles laid down in certain international conventions concerning core human rights’.28 In early 2020, the EU withdrew trade preferences from Cambodia for breaches of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights, among others.29 However, even if only ‘serious and systematic breaches’ of a handful of core human rights conventions were contemplated, the coverage would still be quite extensive. The risk here is not primarily the likely proliferation of listings, but their consistency: there is a danger that individuals and entities responsible for gross violations will be listed alongside the authors of lesser breaches, which, then again, may strengthen allegations of bias towards EU sanctions policy. In addition, war crimes, highly visible and considered particularly repugnant, are not covered under human rights law, but are addressed by international humanitarian law (IHL) instead. Again, a balance must be struck between including core human rights conventions and IHL in the scope of the regime, and keeping the volume and consistency of listings in check.

Third, the listing criteria are as central as conditions for de-listing. Many sanctions regimes allow targets to assume what actions are required for bans to be lifted. In countries that have experienced democratic regression, the holding of free and fair elections can bring about an end to restrictions. Amidst armed conflict, the cessation of hostilities and conclusion of a peace agreement would lead to the termination of sanctions. In instances of nuclear proliferation, the verifiable relinquishment of the military nuclear programme is aimed for. Even if the crisis fails to take the turn desired by senders, designees can achieve de-listing by switching sides or by sitting down at the negotiating table. By contrast, it is unclear what action is required from human rights abusers to be removed from a list. Once included, are there any circumstances in which perpetrators of gross human rights violations can subsequently be taken off the list? Can they make up for the crimes imputed to them at all?

The US Global Magnitsky Act foresees, among other conditions, the possibility of termination of a listing when the designee has ‘credibly demonstrated’ a ‘significant change in behaviour’ and ‘credibly committed’ to not engage in similar actions in the future. While incentivising behavioural change is a classical objective of sanctions, it is hardly plausible to imagine how a designee can do this in practice. The legislation also considers the appropriate prosecution of a designee for the activity for which sanctions were imposed as a reason for delisting. By expecting prosecution by the state authorities, or conceivably by an international court, this option enters the terrain of international criminal justice. It is not unprecedented for the EU to blacklist individuals in the interest of international prosecution, as it kept war criminals from the former Yugoslavia such as Radovan Karadžić or Ratko Mladić under sanctions for several years.30 However, these designees had previously been indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY). In contrast, blacklisting individuals in the expectation that a court will prosecute them equates to paving the way for indictment, thus approximating a soft version of international criminal law. Whether Brussels embraces this objective will ultimately determine who is the real addressee of the regime (the perpetrator or the court expected to prosecute him or her), and will accordingly affect the shape of designation criteria.

Data: sanctionsmap.eu, 2020; Natural Earth, 2020

Closely related to this is the establishment of a guiding mechanism for allocating designations to country-based regimes or thematic lists. How is their coexistence to be managed if designees can theoretically feature on two distinct lists? Should they be included in a horizontal list when no country list is available, or the other way round? Will they feature in both, similar to the Syrians involved in chemical weapons use who appear in the Syria and chemical attacks blacklists? From the above discussion, designees may conclude that their listings are temporary and ‘negotiable’ if included in the country list, or irrevocable if included in the horizontal regime – with potentially far-reaching consequences for the situation addressed.

In sum, these challenges could result in a grim scenario that the drafters of the legislation struggle to avoid. Under this undesirable scenario, the sanctions regime results in an ever-growing list of human rights offenders. As human rights violations occur, the NGO community makes a solid case for the inclusion of more and more perpetrators. Other than becoming a list of egregious human rights abusers, the list does not fulfil any practical purpose. New names keep being added, while none are removed. As the list becomes a ‘gallery of the despicable’, the EU is increasingly perceived as an entity deprived of influence. Add to it the regular de-listing of those individuals who win their cases in Luxembourg because their listings are insufficiently substantiated. And to make things worse, certain individuals and entities get blacklisted for minor violations in isolated incidents. The result could actually do more harm than good to the image of the EU as a human rights advocate.

Global and horizontal: high potential

A horizontal blacklist to advance human rights can be employed to target individuals and entities beyond the reach of country sanctions regimes. While most country sanctions address specific crisis situations – such as electoral violence, armed conflict, the assembling of a nuclear bomb or the spoiling of a peace process – a global, horizontal blacklist has the flexibility to accommodate those responsible for any of those actions. Moreover, a global horizontal blacklist yields unexpected benefits. It can address circumstances which are at the root of human rights abuses which, however severe, do not get reported in the media as major crises. This may include practices by local, foreign or multinational enterprises in conflict zones which fuel fighting, or deprive local communities of their livelihood, pushing them into organised criminality. A global horizontal list may be used to address transnational illicit networks, similar to those operated by Viktor Bout, who brokered arms deals that fuelled several African conflicts, or Abdul Qadeer Khan, who trafficked proliferation-sensitive technology into Iran and Libya.31 Individuals and the entities they control may also be listed because of grand corruption practices. Global Magnitsky designations include Israeli entrepreneur Daniel Gertler, whose activities in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) are linked to bribery scandals. Similarly, the Gupta brothers are listed because, according to the US Treasury, the family ‘leveraged its political connections to engage in widespread corruption and bribery, capture government contracts, and misappropriate state assets’ in South Africa.32

Thus, a global horizontal list constitutes a tool suitable to tackle challenges of a transnational nature which cause severe human rights abuses but are difficult to tackle with country sanctions regimes. The blacklisting of individuals under a global horizontal list notably features the advantage of detaching individuals from their country of nationality, residence or operation. The listing of Daniel Gertler does not constitute a sanctions regime against the DRC or Israel, but rather a sanction against Mr Gertler personally. Illustratively, the name of his country is absent from the title of the sanctions act, highlighting the lack of connection to his origin.

Conclusion

Having established the desirability of a horizontal human rights sanctions regime, the task now is to devise a formula that allows for its creation while obviating the manifold risks associated with its potentially open-ended nature. To keep such risks in check, instead of a general human rights sanctions regime, the EU could devise two specialised horizontal lists. Ideally, this could take the form of two separate legislative acts, or one single sanctions regime featuring two sets of listing criteria.

A first list would address serious and systematic violations of IHL. This would provide the EU with a tool to list those responsible for large-scale breaches committed in the context of hostilities and technically not covered by international human rights law. Given their seriousness and public sensitivity to such abuses, the EU’s failure to list perpetrators of gross violations would undermine Brussel’s credibility as a human rights advocate.

A second list would address cases of grand corruption linked to violations of human rights. Both the US and the Canadian global thematic lists combine human rights protection with the fight against corruption, mirroring the narrative surrounding the death in custody of Sergei Magnitsky. While still absent from the EU’s plans, incorporating an element of fight against corruption will help Brussels to advance its human rights agenda by allowing it to target actors that operate across borders and outside state control.

The inclusion of a human rights/grand corruption element would bring important benefits: first, it would equip the EU with an instrument to target individuals and entities responsible for human rights breaches which are currently outside the reach of country regimes because they operate transnationally and on the margins of state jurisdiction.33 The new horizontal regime will allow the EU to include targets and address violations which are beyond the scope of its current CFSP toolbox – a driving rationale for new policy instruments.

Second, this approach will help the EU limit the proliferation of designations by narrowing the designation criteria. Since only cases of grand corruption leading to serious and systematic human rights violations will be covered under the sanctions regime, the sanctions regimes will focus on a few high-profile, significant episodes. Only instances of overseas grand corruption with major impacts on human rights will be considered for listing. At the same time, the adoption of this blacklist will be an innovation for the EU, providing it with a novel instrument to establish a profile in the fight against corruption. Although the sanctions regimes addressing the misappropriation of state assets in Egypt, Tunisia and Ukraine can be seen as precursors of an EU anti-corruption sanctions regime, the CJEU’s annulment of numerous designations highlight the need to refine Brussels’ approach to the fight against corruption.34 Embracing anti-corruption sanctions will also put the EU on a par with its North American partners.

The combination of an IHL list and a human rights and grand corruption list will represent a mechanism helping the EU to distribute targets among sanctions regimes. Actors involved in IHL violations or in grand corruption with major transnational human rights repercussions will be the subject of horizontal blacklists, while situations of human rights breaches in other contexts such as electoral crises will be best tackled via country sanctions regimes, as has been the case in the past.

In sum, in order to withstand Luxembourg’s scrutiny, it is vital that designations are supported by ample and solid evidence. Civil society organisations can make a useful contribution by collecting open source documentation of gross human rights violations thanks to their specialised local knowledge and presence on the ground. However, the reflection exercise on the sanctions regime currently underway in Brussels should not stop there. Taking as a point of departure the fact that structural divergences in judicial review between the EU and the US preclude mere transplantation, it ought to clarify the objective of the sanctions regime, and communicate it publicly. Determining the rationale of the sanctions regime entails identifying the real addressee of the listings: the designee, country authorities, or an international court. A clarification of the ultimate purpose of the sanctions regime is necessary to manage public expectations, guide the design of the regime, and establish yardsticks for the future evaluation of its performance.

References

1) Rikard Jozwiak, “Netherlands Proposes New EU Human Rights Sanctions Regime”, Radio Free Europe, November 19, 2018.

2) Thomas Biersteker and Clara Portela, “EU sanctions in context: Three types”, EUISS Brief no. 26, July 2015.

3) Clara Portela, “EU sanctions as a foreign policy tool: Do they work?”, in Sven Gareis, Gunther Hauser and Franz Kernic (eds), The European Union: A global actor? (Opladen: Budrich, 2012), pp. 429-39.

4) Thomas Biersteker, Sue Eckert and Marcos Tourinho (eds), Targeted Sanctions. The impacts and effectiveness of UN action (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2016).

5) Executive Order 13818, “Blocking the Property of Persons Involved in Serious Human Rights Abuse or Corruption” of 21 December 2017, built upon the US Congress’s “Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act” of 2016.

6) Bill S-226, “Justice for Victims of Corrupt Foreign Officials Act”, October 18, 2017.

7) See listings at https://laws.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/SOR-2017-233/page-2.html#h-842596

8) Stef Blok, “Closing Remarks at a meeting on the EU Global Human Rights Sanction Regime”, The Hague, November 20, 2018.

9) Open letter from non-governmental organisations in support of a targeted, global EU human rights sanctions regime, December 5, 2018, https://www.humanrightsfirst.org/sites/default/files/European-Union-Sanctions-Letter.pdf

10) European Parliament resolution on a European human rights violations sanctions regime 2019/2580(RSP), Strasbourg, March 14, 2019.

11) 3738th Council meeting Foreign Affairs, Doc. 14949/19, Brussels, December 9, 2019, p.6.

12) Lorand Bartels, Human Rights Conditionality in the EU’s International Agreements (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2005).

13) Clara Portela, “Where and why does the EU impose sanctions?”, Politique Européenne, vol. 17, no. 3, 2005, pp. 83-111; Joakim Kreutz, “Human Rights, Geo-strategy, and EU Foreign Policy, 1989–2008”, International Organization, vol. 69, no. 1, pp. 195-217.

14) Stephanie Chan, “Principle versus Profit: Debating human rights sanctions”, Human Rights Review, vol. 19, no.1, 2018, pp. 45-71.

15) Op. Cit, “EU sanctions as a foreign policy tool”.

16) Elena Baracani, “US and EU Strategies for Promoting Democracy”, in Federica Bindi and Irina Angelescu (eds), The Foreign Policy of the European Union (Washington, DC: Brookings, 2012), pp. 306-24; Inken von Borzyskowski and Clara Portela, “Sanctions Co-operation and Regional Organisations”, in Stephen Aris, Aglaya Snetkov and Andreas Wenger (eds), Inter-organisational Relations in International Security: Cooperation and Competition (Abingdon, Routledge, 2018), pp. 240-61.

17) Cristiane Carneiro and Learte Apolinário, “Targeted versus conventional economic sanctions: What is at stake for human rights?”, International Interactions, vol. 42, no. 4, 2016, pp. 565-89.

18) Elena Servettaz, “A Sanctions Primer: What happens to the targeted?”, World Affairs, vol. 177, no. 2, 2014, pp.82-9.

19) Michael Brzoska, “From dumb to smart? Recent reforms of UN sanctions”, Global Governance, vol. 9, no. 4, 2003, pp. 519-35.

20) Parliament of Canada, House of Commons Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development, Evidence, October 31, 2016.

21) Clara Portela, “Are EU sanctions ‘targeted’?”, Cambridge Review of International Affairs, vol. 29, no. 3, 2016, pp. 912-29.

22) Viktor Szép, “New Intergovernmentalism meets EU Sanctions Policy”, Journal of European Integration, 2019.

23) See EU sanctions map, https://www.sanctionsmap.eu/#/main.

24) See respectively Council Decision 2014/386/CFSP of 23 June 2014 concerning restrictive measures in response to the illegal annexation of Crimea and Sevastopol; Council Decision 2014/145/CFSP of 17 March 2014 concerning restrictive measures in respect of actions undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine; and Council Decision 2014/119/CFSP of 5 March 2014 concerning restrictive measures directed against certain persons, entities and bodies in view of the situation in Ukraine.

25) See Council Decision 2010/573/CFSP of 27 September 2010 concerning restrictive measures against the leadership of the Transnistrian region of the Republic of Moldova.

26) House of Lords, “The Legality of EU Sanctions”, European Union Committee, 11th Report of Session 2016-17, February 2, 2017.

27) Quoted in Ibid.

28) Regulation (EU) No 978/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2012 applying a scheme of generalised tariff preferences, p.3.

29) European Commission, Factsheet, "Trade/Human Rights: withdrawal of Cambodia’s preferential access to the EU market", February 12, 2020.

30) Council Common Position 2004/694/CFSP of 11 October 2004 on further measures in support of the effective implementation of the mandate of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY),

31) Peter Wallensteen and Helena Grusell, “Targeting the right targets? The UN use of individual sanctions”, Global Governance, vol. 18, no. 2, 2012, pp. 207-30; Clara Portela, “The EU’s evolving responses to nuclear proliferation crises”, Non-Proliferation Papers, no. 46, SIPRI, Stockholm, 2015.

32) “South Africa’s Gupta brothers sanctioned by US over ‘corruption’”, BBC News, October 10, 2019.

33) Raoul Wallenberg Institute, The Nexus between Anti-Corruption and Human Rights, Lund, 2018.

34) Charlotte Beaucillon, “Opening up the horizon: The ECJ’s new take on country sanctions”, Common Market Law Review, vol. 55, no.1, 2018, pp. 387- 416.