On 19 February 2024, the European Union launched Operation Aspides, sending initially four frigates under the EU flag to protect shipping in the Red Sea and northwest Indian Ocean in response to Houthi attacks from Yemen. The EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) has always been about capabilities but also missions and operations to project power and protect EU interests around the world. Currently, some 3 500 military personnel and 1 300 civilian experts are deployed by the EU in Europe, Africa and Asia (1). For more than 20 years, the EU has deployed troops beyond its borders. But what has been the impact? And what is the future of the EU as a strategic actor? At a time when the use of military power is surging around the world, the EU is faced with challenging policy choices and trade-offs, on where and how to act, as it takes on a larger role in security and defence. To help clarify these choices, this Brief presents three alternatives for future EU military CSDP missions and operations:

- Europe first;

- Protecting the commons; and

- Back to the future.

Assessment and impact

EU military CSDP missions and operations have made a difference. Operation Artemis saved lives in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in 2003 and Operation Althea has provided stability in Bosnia-Herzegovina since 2004, while Operation Atalanta has contributed to deterring pirates off the Horn of Africa since 2008. More recently, in November 2022 the EU swiftly launched a Military Assistance Mission (EUMAM) in support of Ukraine and will have trained 60 000 Ukrainian troops by the end of summer. However, the record is less clear in other cases. In the Sahel, the EU has spent more than €600 million on civil and military missions over the past ten years, training some 30 000 members of the security forces and 18 000 soldiers but with little positive effect (2).

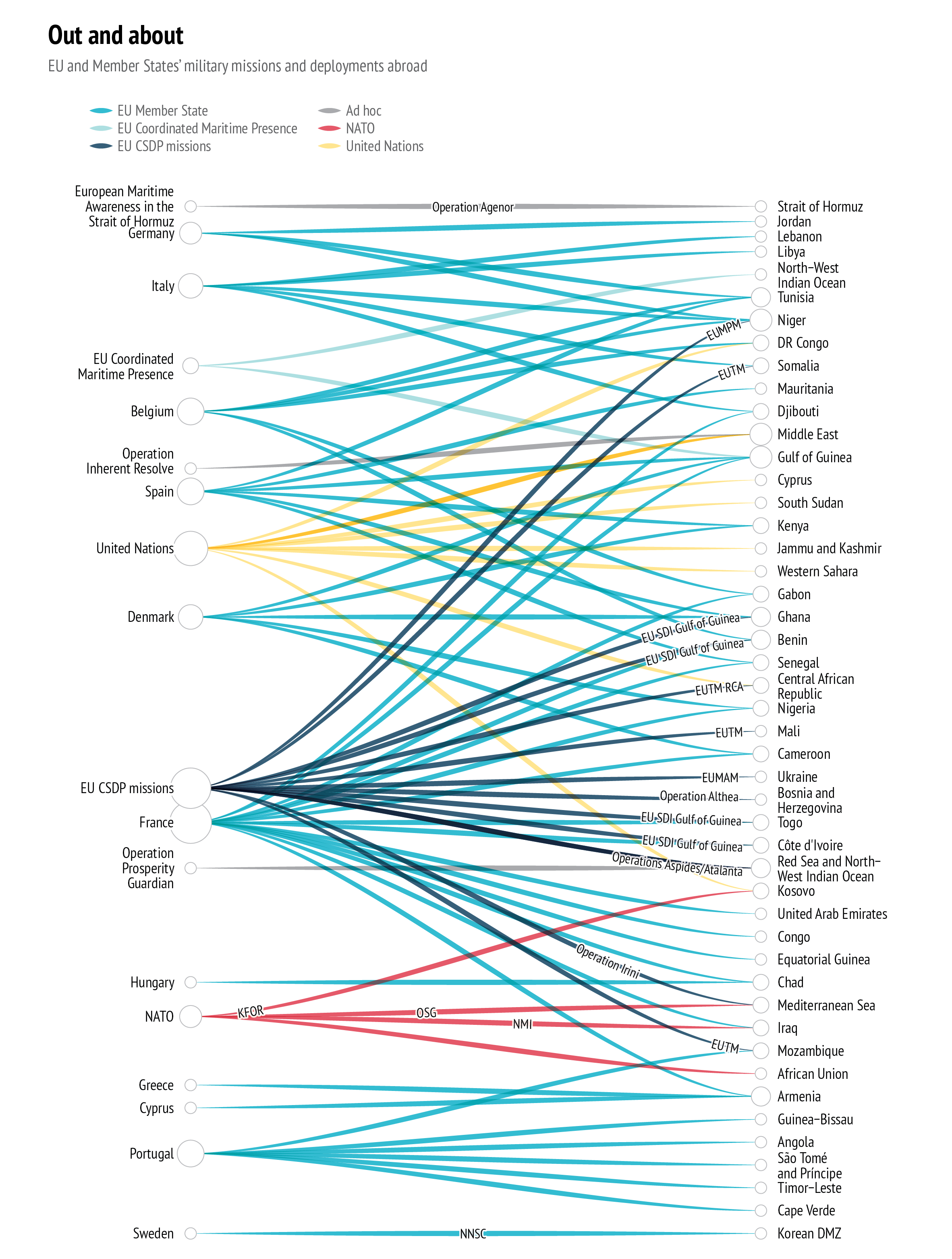

The EU’s CSDP missions and operations are assessed through a regular six-monthly reporting mechanism and in occasional comprehensive Strategic Reviews by the Political and Security Committee (PSC). A key question in these official EU assessments is how a mission or operation measures up against its mandate, but also on technical and administrative efficiency (e.g. how many troops trained, how much budget spent, etc). Assessments by outside experts tend to focus more on the strategic impact on reducing conflict (3). What constitutes success can therefore be difficult to agree on. Regardless of the approach, it should be recalled that EU missions are often mandated to implement technical tasks, such as training or capacity building, but sometimes in countries where there is little willingness on the part of the host government to improve oversight and build professional armed forces (4). This is even more the case when others offer cooperation on more attractive terms. For example, in Mali, the Central African Republic (CAR), Libya and Sudan the governments have turned to Russia’s Wagner Group for help in fighting rebel groups, personal protection and to ensure regime stability with little concern for accountability or human rights, leading the EU to suspend security cooperation (5). EU missions and operations can sometimes overlap with bilateral efforts of Member States and other organisations which can also complicate matters in generating forces and resources in the EU, and on the ground in partner countries (6). In the diagram opposite, EU, NATO, UN and individual Member States’ missions and deployments are illustrated.

Nevertheless, EU military CSDP missions and operations are often assessed as having an impact, albeit limited due to constraints such as lack of resources and unfilled vacancies; high turnover of staff; and in training missions, lack of follow-up and too few instructors with necessary language skills. National caveats, risk aversion, lack of coordination with other EU programmes, poor strategic communication, and restrictions on providing arms and equipment do not help either (7).

Maybe if EU missions and operations were larger and better resourced, the results would be better. The European Peace Facility (EPF) and the willingness to now fund arms could make the EU’s offering more appealing. But vast resources were spent by Western powers on security and training of local armies in Iraq and Afghanistan to little effect. The Iraqi army’s collapse in the face of the Islamic State in 2014-2015 came three years after the US and coalition forces had spent eight years and at least $25 billion in training and equipment (8). The equally spectacular disintegration of the Afghan army in 2021 despite 20 years and $90 billion of international support show that time and money are not deciding factors (9). In fact, several studies even suggest that foreign military training contributes to instability, insecurity and coups, although others disagree (10). In any case, massive amounts of donated military equipment were lost in Iraq and Afghanistan and are now fuelling conflicts in other parts of the world (11). In much of the literature, it is unclear how much lasting impact foreign military training, security sector assistance (SSA) and security sector reform (SSR) missions really have.

Future military CSDP operations

Given the mixed record and lessons learned from EU military CSDP missions and operations over the past 20 years, what is their future? With no end in sight to Russia’s war against Ukraine, or the conflicts in the Middle East, across Africa and in East Asia, the EU needs to stay globally engaged. But with limited resources, choices must be made on where and how the EU should act. In the following section, three alternatives for future EU military CSDP are discussed.

Europe first

In this scenario, the EU and its Member States remain focused on supporting Ukraine but also stabilising the Eastern neighbourhood, including the Western Balkans. EU military CSDP missions and operations are primarily to support EU candidate and partnership countries. Building on the widely supported EUMAM Ukraine in which 24 Member States and Norway provide military training to Ukrainian troops, future missions could include military training and capacity building for Moldova and Georgia, and perhaps Armenia and Azerbaijan. The continuing support for Operation Althea after 20 years in Bosnia-Herzegovina shows the commitment of the EU Member States to military CSDP missions in Europe and the Eastern neighbourhood.

The EU may have to be ready to assume a larger role in stabilising peace and security in the post-Soviet space.

The political buy-in and ownership of EU Member States and of the partner countries in the Eastern neighbourhood for EU CSDP missions and operations is key in this alternative and can be expected to remain high. Depending on the future political direction of the United States, and NATO, the EU may have to be ready to assume a larger role in stabilising peace and security in the post-Soviet space (12). Moldova and Georgia are both candidate countries of the Union and in the event of armed aggression against them, the EU would have to act. The current CSDP Missions in Georgia, Moldova and Armenia are civilian but could in the future be complemented by military ones.

Protecting the global commons

In the second scenario, the EU and its Member States continue to support Ukraine ‘for as long as it takes’ but with the maritime domain increasingly contested, EU military CSDP shifts from training missions to naval operations protecting global trade routes and undersea infrastructure on which Europe’s and the global economy rely. The EU is committed to enhance the maritime security of the Union and its Member States, including by exercises with partners and naval visits. In line with the Strategic Compass, the EU adopted a revised Maritime Security Strategy (EUMSS) in 2023 (13). This strategy aims to strengthen the EU’s ability to respond to threats in the maritime domain and protect its interests at sea. While not all EU Member States are coastal states, all depend on Europe having access to open sea routes and seabed infrastructure.

Following the Maritime Strategy and building on Operations Aspides, Atalanta and Irini as well as the Coordinated Maritime Presences (CMP) in the Gulf of Guinea and northwest Indian Ocean, the EU can provide significant added value in the maritime domain. Demand for EU naval presence around the world is growing and existing areas of operations can be complemented by new activities in the Indo-Pacific. EU Member States are seemingly more able and willing to deploy naval forces than land forces as several Member States have shown by contributing maritime assets to US-led operations, such as Prosperity Guardian, and to the French-led Operation Agenor in the Strait of Hormuz (14). EU-supported logistical bases or maritime hubs in key ports from the Red Sea to the Strait of Malacca could also be contemplated to facilitate permanent European naval presence in the Indian Ocean and beyond.

Back to the future

In the third scenario, the EU and its Member States stay true to the ambition in the Strategic Compass to be able to respond to imminent threats or quickly react to crises outside the Union. In this scenario, the Rapid Deployment Capacity (RDC) will be at the centre of future military CSDP operations, giving the Union the means to swiftly deploy up to 5 000 troops with the necessary strategic enablers. By 2025, the EU is committed to establishing the RDC, including command & control functions, flexible decision-making arrangements, and an extended scope of common costs in place (15).

In this future, the focus of EU military CSDP is shifting back from advising, training and capacity-building missions to crisis management and peace support operations at scale. During the early years of the ESDP/CSDP, EU Member States provided soldiers and resources for robust military interventions far away from Europe (e.g. 3 700 in EUFOR Chad/CAR; 1 800 in Operation Artemis in DRC). These operations were often in support of larger UN efforts, but an increasingly paralysed UN Security Council means that the EU may have to shoulder a larger role for conflict management on its own. And that could require the EU to intervene in more than one place at the same time.

Conclusion

To be able to respond early and forcefully to external conflicts and crises is a strategic priority for the EU. The recent launch of Operation Aspides and the training of tens of thousands of soldiers in EUMAM Ukraine show that the Union can respond when needed. However, the disappointing results of several EU military CSDP training and capacity-building endeavours in the Sahel also demonstrate the challenges in crafting missions that can deliver lasting impact.

This Brief has outlined three alternative scenarios for future military CSDP missions and operations. These alternatives are not mutually exclusive but can help in focusing the discussion on what role the EU can and should play as a growing security provider in an unstable world. Each alternative has its merits. Nevertheless, with Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine continuing unabated and given the lessons learned from 20 years of military CSDP missions and operations, the ‘Europe first’ alternative emerges as the most likely and preferred option. But given Europe’s reliance on seaborne trade and seabed infrastructure, the EU should also take on greater responsibility for protecting the global commons at sea. This does not mean that there will be no European military engagement in other parts of the globe. As the diagram on page 2 shows, EU Member States are engaged through the UN, NATO, ad-hoc coalitions, and in bilateral military and SSA/SSR missions in many places around the world. However, for the EU, a combination of Europe-focused missions and maritime operations would not only defend Union values and interests, but also contribute to international security and the common good.

References

* The author would like to thank colleagues and subject matter experts for comments and suggestions, Sascha Simon for excellent research assistance and Christian Dietrich for his work on the graphics.

1. European External Action Service (EEAS) (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/_en).

2. ‘Les missions de l’UE au Sahel ont échoué à renforcer la démocratie, selon Josep Borrell’, Euractiv, 13 September 2023 (https://www.euractiv.fr/section/afrique/news/les-missions-de-lue-au-sahel-ont-echoue-a-renforcer-la-democratie-selon-josep-borrell/).

3. See, for example, Sabatino, E. et al, ‘Case studies of the EU’s CSDP activity’, Engage Paper No 19, March 2023 (https://www.engage-eu.eu/publications/case-studies-of-the-eus-csdp-activity).

4. Van der Lijn, J., ‘EU Military Training Missions: A Synthesis Report’, SIPRI, Stockholm, May 2022 (https://www.sipri.org/publications/2022/policy-reports/eu-military-training-missions-synthesis-report).

5. Rampe, W., ‘What Is Russia’s Wagner Group doing in Africa?’, CFR, 23 May 2023 (https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/what-russias-wagner-group-doing-africa); Adegoke, Y., ‘Why Wagner is winning hearts in the Central African Republic’, BBC News, 11 December 2023 (https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-67625139).

6. While cooperation takes place, some competition and duplication cannot be avoided.

7. ‘EU Military Training Missions: A Synthesis Report’, op. cit.

8. Scher, A., ‘The collapse of the Iraqi army’s will to fight: A lack of motivation, training, or force generation?’, Military Review, 19 February 2016 (https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/Online-Exclusive/2016-Online-Exclusive-Articles/Collapse-of-the-Iraqi-Army/).

9. Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, ‘Why the Afghan Security Forces Collapsed’, February 2023 (https://www.sigar.mil/pdf/evaluations/SIGAR-23-16-IP.pdf).

10. Savage, J.D., and Caverley, J.D., ‘When human capital threatens the Capitol: Foreign aid in the form of military training and coups’, Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 54, No 4, July 2017, pp. 542-557. (https://www.jstor.org/stable/44511233); Seymour, L., Does US military training incubate coups in Africa? The jury is still out’, The Conversation, 28 September 2020, p. 2 (https://theconversation.com/does-us-military-training-incubate-coups-in-africa-the-jury-is-still-out-146800).

11. Kathju, J., ‘U.S. arms left in Afghanistan are turning up in a different conflict’, NBC News, 30 January 2023 (https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/us-weapons-afghanistan-taliban-kashmir-rcna67134).

12. Pietz, T., ‘Zeitenwende or standstill in EU crisis management operations?’ Internationale Politik Quarterly, 7 November 2022 (https://ip-quarterly.com/en/zeitenwende-or-standstill-eu-crisis-management-operations).

13. Joint Communication on the update of the EU Maritime Security Strategy, 10 March 2023 (https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-7311-2023-INIT/en/pdf).

14. Operation Agenor (https://www.emasoh-agenor.org/about-4)

15. EEAS, ‘European Union Rapid Deployment Capacity’, October 2023 (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/2023/2023-10-EU-Rapid-Deployment-Capacity_EN.pdf).