On 24 February 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The fighting ever since has led both sides to use up arms and ammunition at a rate not seen in Europe since World War II (1). To sustain the fight, Ukraine needs a continuous supply of weaponry. In response, the United States and many European countries have transferred large amounts of arms and equipment to Ukraine (2). These supplies are now running low and European governments are busily working not only on supplying Ukraine and replenishing their own stocks, but also on acquiring new weapons and equipment in the largest rearmament effort in Europe since the 1950s. To speed up deliveries, the EU agreed in March 2023 to launch a ‘Collaborative Procurement of Ammunition’ project to which EU Member States and Norway have signed up to aggregate orders and place them together with industrial partners through the European Defence Agency (EDA) (3).

However, despite these endeavours, much criticism has been levelled at the slow pace of rearmament. Many argue that more European cooperation on defence acquisition and arms procurement would not only make buying arms faster and cheaper, but also strengthen the European defence industrial base by consolidating demand (4).

But why are EU Member States buying so few weapons together, and is buying together always better? In contrast to much conventional wisdom, this Brief argues that European countries are likely collaborating far more on defence acquisition and arms procurement than is commonly believed, as not all armaments collaboration is reported by Member States. Thus not all such efforts are reflected in the official data (5). By focusing more on desired output and pragmatic forms of collaboration rather than artificial benchmarks, and using existing tools and instruments, the EU and its Member States may be able to better collaborate on defence acquisition and arms procurement, where and how it makes most sense.

This Brief consists of three main sections. The first section reviews the arguments for and against more collaboration and the record of European armaments collaboration. While the record is mixed, this Brief argues that the key is to better understand under what conditions common defence acquisition and joint arms procurement make most sense (and when it does not). To facilitate understanding, the following section proposes a typology of six different options for collaboration labelled: (1) common acquisition;(2) joint acquisition; (3) parallel acquisition; (4) common procurement; (5) joint procurement; and (6) parallel procurement. The third section presents different options for managing the various forms of collaboration.

Rearming

After many years of underinvestment in defence, EU Member States are rearming. According to the latest EDA data, EU Member States collectively spent €52 billion on defence investment in 2021, of which €43 billion went into buying equipment and €9 billion into research and development (R&D) (6). This is more than double the €21 billion EU Member States dedicated to new defence equipment at their low point in 2014, in constant 2021 prices (7).

Many collaborative armaments projects are politically or industrially motivated rather than capability driven.

Reaching a record high of 24 % in 2021, EU Member States have met and exceeded the agreed EDA benchmark of dedicating 20 % of their defence spending to investment three years in a row (8). Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, EU Member States are planning to increase their defence expenditure by some €70 billion by 2025 to fill existing capability gaps(9). Most prominent was Germany’s announcement to create a €100 billion special budget (Sondervermögen) for new investments and armaments projects to be disbursed over the next several years (10). Accordingly, the European defence industry has reported many new contracts for arms and equipment in 2022 but expects much more in the years to come (11).

Why buy weapons together (or not)?

Defence acquisition is the process of defining, obtaining and delivering arms and equipment on time, within budget, and meeting set requirements. The terms defence acquisition and defence procurement are often used interchangeably even in policy documents. It is, however, useful to analytically distinguish acquisition as a broader concept including the analysis and decisions of what to buy, how to buy it, and how to support the systems and platforms once bought, from procurement which is the negotiation and management of contracts (12).

The terms common and joint are also often used interchangeably but can be analytically and usefully defined as well. At NATO, for example, ‘common funding’ entails contributions from all Allies, with all Allies collectively deciding what is eligible for common funding and how much can be spent each year, while ‘joint funding’ means that the participating countries in a specific project or initiative can identify the priorities and the funding arrangements (13). In keeping with the NATO definitions, common in the EU context would designate, for example, acquisition and procurement using the European Peace Facility, to which all EU Member States contribute and in which they thus have a voice. Joint would be used to describe projects or programmes conducted by Member States bilaterally or minilaterally.

EU Member States may see more advantages in collaboration than is commonly believed.

Defence is a national responsibility and most defence acquisitions are made by a government for its armed forces. There are many reasons for national acquisition. Different geographic imperatives, strategic cultures and war fighting doctrines all play a role in setting requirements for defence equipment, as do domestic defence industry policies and international security alliances, and of course budgets. In some countries, there are also legal limitations on international armaments cooperation (14).

Many however, argue for more European cooperation on defence acquisition and arms procurement. The most prevalent reasons given are lower costs resulting from sharing R&D and economies of scale in production but also increased operational efficiency by fielding the same types of equipment (15). That supposedly remains below the agreed EDA benchmark of 35 % of total equipment spending by Member States is commonly cited as evidence that Member States are underperforming (16). But is it really cheaper and better to buy armaments together? And are EU Member States not collaborating enough?

There is a long history of joint defence acquisition and arms procurement in Europe. Many studies show that such collaboration has indeed delivered capabilities individual countries could not have acquired on their own, but also how armaments collaboration can lead to capabilities many years late and above cost, and at times be ‘a general waste of time and money’ (17). In fact, a review of the literature reveals many anecdotal examples but little systematic evidence of collaborative armaments programmes either providing substantive savings as a rule, or by default being late and above cost. One conclusion from a comprehensive study of European defence equipment collaboration simply states that ‘the advantages of cooperative programmes depend on how well or poorly they are managed and the use (or not) of best practice’ (18).

A major challenge for analysing armaments cooperation is that there is no common analytical tool for measuring success or failure. Costs and prices are notoriously difficult to compare since they depend on what is included, such as R&D, sustainment and time of delivery (19). How to weigh cost vs performance is also far from self-evident. Moreover, many collaborative armaments projects are politically or industrially motivated rather than capability driven, making any judgement of what counts as success or failure difficult to discern (20). One thing that scholars studying acquisition cooperation seem to agree on, however, is that transaction costs associated with international armament cooperation should not be underestimated. As emphasised in the foreword endorsing a major comparative study of defence acquisition in and among France, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States, ‘[p]eople working on international cooperative programs quickly discover that different budget cycles, political issues, and cultural perspectives can exacerbate small problems and, in some cases, create larger ones’ (21).

To what extent do EU member states buy weapons together

Given the paucity of strong empirical evidence for or against collaborative defence acquisition, cooperation should only be expected when advantages are clear – however defined – or when no other alternatives exist.

But EU Member States may see more advantages in collaboration than is commonly believed. According to the most recent EDA data, Member States allocated €7.9 billion to European collaborative defence equipment procurement projects in 2021 (22). This was the highest value ever recorded by the EDA and almost double what was noted in 2020, but at 18 % of their total defence equipment procurement, still below the 35 % benchmark for European collaborative defence equipment procurement set in 2007. However, according to the EDA, the increase is at least partially caused by a higher number of Member States providing data. In 2021, 14 Member States reported data on joint European defence equipment procurement whereas in 2020, only 11 Member States did (23). Does that mean that EU Member States really have increased their collaboration on European procurement since 2020, and are we above or below the 35 % benchmark? With 12 unidentified Member States not having provided data, we simply do not know (24). Moreover, it can be debated what should be defined as European collaborative defence equipment procurement. In fact, there may be more ‘collaborative’ buying than is commonly assumed by commentators and officials alike, as discussed below. Regardless, as the EDA figures indicate and research for this study suggests, there are many significant ongoing collaborative defence acquisition projects in Europe (25).

How to buy weapons together?

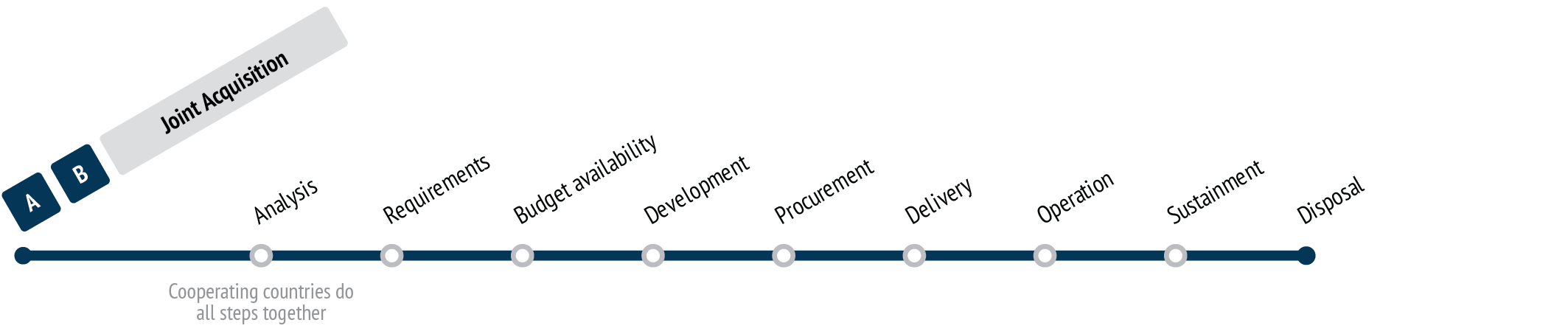

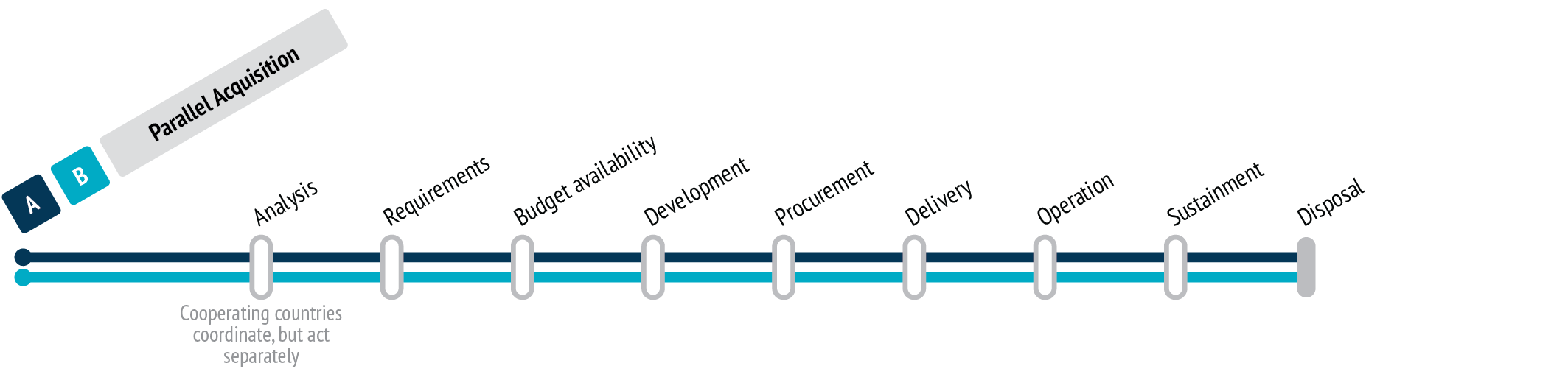

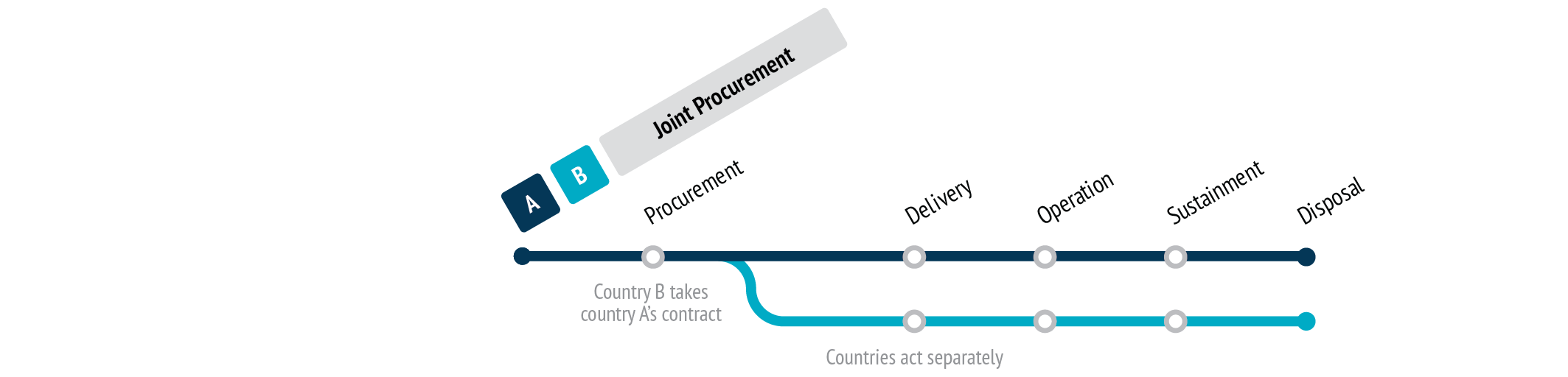

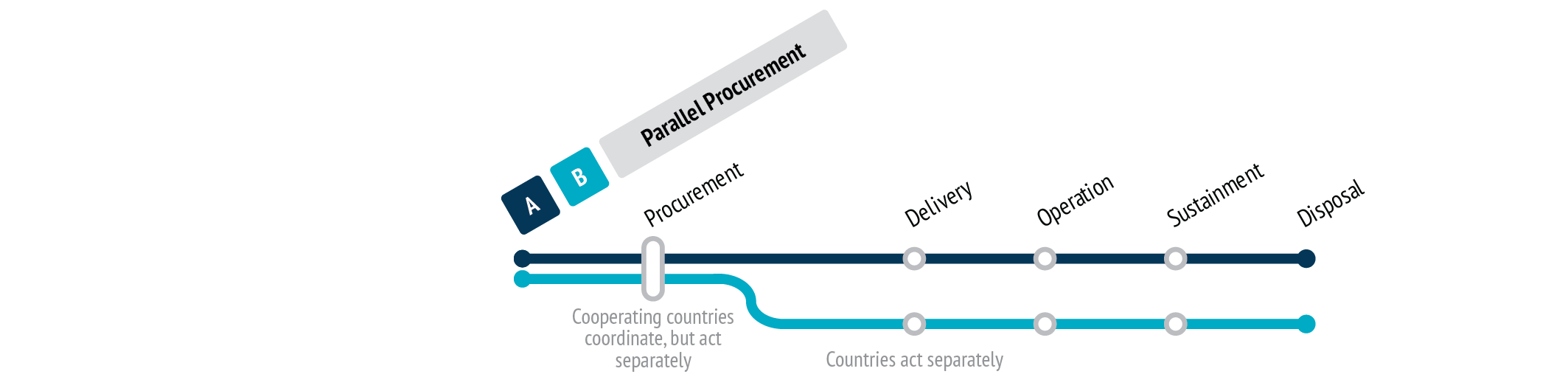

For analytical purposes, countries can collaborate on acquiring weapons together in at least six different ways. To differentiate between them, we propose a typology divided into (1) common acquisition; (2) joint acquisition; (3) parallel acquisition; (4) common procurement; (5) joint procurement; and (6) parallel procurement (26).

Common or joint acquisition

The most comprehensive but also most complex form of acquisition collaboration would be for all EU Member States (or NATO Allies) to agree on requirements and funding for a weapon system, and then commonly develop and procure the equipment together. A less comprehensive form is for two or more countries, but not all, to jointly undertake the acquisition. In some cases, the collaboration may extend to maintenance and support, or even operation of the acquired equipment. Examples of multilateral joint acquisition are the Multinational Multi Role Tanker Transport (MRTT) Fleet (MMF) of 10 Airbus A330 MRTT aircraft; the Strategic Airlift Cooperation’s (SAC) three Boeing C-17 aircraft for strategic transports; and NATO’s Airborne Early Warning & Control (NAEW&C) Force of 14 Boeing E3A AWACS planes. In each of these cases, a group of countries harmonised national requirements for strategic capabilities that could not be afforded individually, and jointly acquired and operate them (27).

There are also several cases of bilateral joint defence acquisition. One such ongoing example is the joint Belgian-Dutch minehunter replacement programme in which 12 vessels – six for the Netherlands and six for Belgium – are being built under one €2 billion contract awarded to a consortium led by Naval Group in 2022. After agreeing on requirements, Belgium took the lead in the procurement process but with Dutch participation in the evaluation (28). Another recent example in the naval domain is the 2017 agreement between Germany and Norway to jointly develop and acquire six U212 Common Design (CD) identical submarines – four for Norway and two for Germany – as well as jointly training the crews. The €5.5 billion contract between Germany, Norway and shipbuilder Thyssen-Krupp was signed in August 2021, with construction beginning in 2023 and deliveries expected between 2029 and 2034 (29).

Common or joint acquisition requires extensive negotiations and agreement not only on requirements but also on development and procurement. It can yield many advantages but also be time consuming. In the case of MMF, for instance, it took eight years from the launch of the harmonisation of requirements in 2012 to the delivery of the first aircraft in 2020, but now six European countries have a capability that they would not have been able to acquire on their own. However, this is an example of a rather fast joint acquisition, and national programmes can be very time consuming as well (30).

Parallel acquisition

A less comprehensive but simpler form of acquisition that still provides the advantages of cooperation is for two or more collaborating countries to conduct acquisition separately but in transparent parallel processes. Separate processes reduce risks and complications that may result from certain countries’ national parliamentary approvals or legal limitations to armaments cooperation, while still allowing for the advantages of cooperating on requirements and negotiations vis-à-vis industry regarding price and delivery times. Parallel acquisition also eliminates the risk of unexpected changes of government or parliamentary majorities in one or more participating countries delaying or derailing the acquisition for all (31). In a parallel acquisition, each country is responsible for its own processes, but based on common requirements, and benefitting from cooperation on maintenance, logistics and training.

An example of an ongoing parallel acquisition is the separate but coordinated selections for tracked Infantry Fighting Vehicles (IFV) concluded by Slovakia and the Czech Republic in 2022. Both countries sought to replace their Soviet-era armoured vehicles with western equipment and launched separate programmes but with similar requirements and timelines, and received bids from the same companies. In May 2022, after extensive trials, the Slovak Ministry of Defence publicly released its detailed evaluation of the bids, including offered unit price and total cost, recommending the acquisition of 152 BAE Hägglunds CV90 MKIV from Sweden for €1.3 billion (32). Having largely the same requirements as Slovakia, the Czech government then cancelled its own acquisition process in July 2022 and began negotiations with Sweden for 200 CV90 MKIV, in coordination with Slovakia (33). The Czech Republic and Slovakia are not only cooperating on the technical specifications of these vehicles but also on industrial, operational and future development aspects (34). While each country concludes its own separate contract, the acquisition and subsequent operation and training can thus be highly coordinated (35). Both countries will also join eight other European countries in the CV90 user group, further benefitting from joint armaments cooperation (36).

Common or joint procurement

Some defence systems may not need a lengthy harmonisation of requirements or development. For joint procurement of such equipment, there are different options. One option is for a country to procure the equipment on behalf of one or more countries as well as for its own needs. In that case, this country ‘A’ acts as the procurement agent for itself but also for countries B and C in negotiations with vendors. Another option is for country A to allow countries B and C to place orders within an existing framework contract that country A already negotiated with industry.

A current example of the first option is the agreement among several European countries in 2020 to jointly procure armoured tracked All-Terrain Vehicles (ATV). Based on a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between six countries to jointly acquire ATVs, a comprehensive framework agreement was signed in 2022 between Sweden, acting as procurement authority also for the others, and BAE Hägglunds. Under the framework agreement, the group of countries can place orders for BvS10 ATVs until 2029 (37). In December 2022, Germany, Sweden and the UK placed a first joint order for 436 vehicles with deliveries beginning in 2024. A second order for 200 more vehicles for Germany is under preparation (38).

An example of the second option is the 2021 agreement between the Netherlands and Norway under which the Netherlands procured GM200 MM/C multi-mission radars for the Norwegian army. The Netherlands had already ordered nine such systems from Thales in 2019 and exercised an option to buy five additional, identical units for Norway in a government-to-government sale to be delivered from the end of 2023 (39). A similar agreement is being negotiated between the Netherlands and Denmark but will also include procurement of other equipment (40). Another example is recent orders placed by Estonia and Latvia for anti-tank weapons within an existing framework agreement between Sweden and SAAB from June 2019, which allows Sweden, Estonia and Latvia to place orders for Carl-Gustaf M4 weapon systems during a ten-year period (41). In January 2022, Lithuania joined the same framework agreement and placed a first order of Carl-Gustav ammunition (42).

Parallel procurement

In addition to the alternatives above, there is the possibility of having separate procurement processes but coordinating them for price and delivery schedules. Keeping the procurement contracts separate eliminates legal uncertainties or bureaucratic complications often associated with joint procurement. At the same time, it still allows for negotiating better prices by consolidating demand and coordinating delivery schedules. A recent example of such parallel procurement was the signing of two separate but simultaneous orders by Finland and Sweden for 57mm ammunition from BAE Systems Bofors in December 2022. The procurement was coordinated closely by Finland and Sweden to procure the same type of ammunition simultaneously but separately, with minimal extra bureaucracy or risk (43).

European-level support

There is no lack of European defence cooperation. A recent study by the EUISS mapped some 200 European defence partnerships between the EU Member States, and between Member States and strategic partners such as the United States or Norway (44). Many of these are focused on armaments collaboration, including acquisition and procurement, of which some have been mentioned above. To further assist EU Member States and partner countries, there are also several entities in Europe mandated to support armaments collaboration.

NATO Support and Procurement Agency (NSPA)

In the transatlantic framework, the NATO Support and Procurement Agency provides since 1958 acquisition, logistic, operational and systems support, including related procurement to NATO Allies and partner nations. These range from the multinational acquisition of complex platforms, such as aircraft and helicopters, to the provision of fuel, spare parts and ammunition, or services such as maintenance and transportation. The centralisation of functions across for providing comprehensive support and economies of scale. NSPA is customer-funded on the basis of a ‘no profit-no loss’ logic, and currently supports more than 90 weapon systems and 170 projects, including the management of the C-17 fleet on behalf of the 12 SAC member nations and the MMF/MRTT fleet for the six participating countries (45).

Organisation Conjointe de Coopération en matière d’Armement (OCCAR)

OCCAR is the European Organisation for Joint Armament Cooperation for the management of cooperative defence equipment programmes. It was established in 1996 to support armaments cooperation. The current OCCAR Member States Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the United Kingdom have signed a convention allowing OCCAR to award contracts and employ its own staff. OCCAR employs a concept of ‘global balance’ which involves the calculation of a multi-programme/multi-year balance of work share against cost share. The OCCAR portfolio includes programmes such as A400M, BOXER, COBRA, ESSOR, FREMM, FSAF-PAAMS, LSS, MALE RPAS, MMCM, MUSIS, PPA and TIGER (46).

While the record is mixed, there may in fact be more armaments cooperation than is often believed and in many different forms.

European Defence Agency (EDA)

In the EU context, the European Defence Agency is, as described in the Treaty on the European Union, ‘the Agency in the field of defence capabilities development, research, acquisition and armaments’ (47). The agency shall also ‘participate in defining a European capabilities and armaments policy’ (48). Following the adoption of the Defence and Security Procurement Directive 2009/81/EC, a dedicated experts’ group – the Defence Acquisition Experts’ Network – was set up by the EDA to share Member States’ experiences of defence procurement and lessons learned. Since 2013, the EDA has increasingly focused on cooperative procurement issues in close cooperation with Member States and the European Commission.

The EDA can support Member States’ acquisition and procurement in several ways. For example, the agency can assist Member States in harmonising requirements, develop defence technology research, and create joint military capabilities. To this end, the EDA can contract for studies funded by its operational budget to prepare Member States’ investments in collaborative projects through so-called EDA Ad-Hoc Project Arrangements (PAs) (49). PAs can include options for Member States to activate separate projects in which they mandate the EDA to manage financial contributions and undertake tendering and contracting on their behalf. Examples of activities which include joint acquisition by the EDA are its Helicopter Training Portfolio, and MARSUR, AIRMEDEVAC, and EU SATCOM services. Under these PAs, participating Member States have mandated the EDA to act as contracting authority for the award of contracts, applying competitive tendering. Previously, the EDA has also taken a leading role in the joint procurement of anti-tank ammunition for several Member States (50).

On 20 March 2023, EU Member States and Norway signed an EDA PA for the collaborative procurement of ammunition to replenish Member States’ national stockpiles and support Ukraine. The PA provides a seven-year framework for EU Member States and Norway to jointly procure ammunition of various kinds by aggregating, coordinating and agreeing on contracts with European industry through the EDA (51). Other areas for joint procurement being prepared by the EDA are for soldier systems, and chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear equipment (52).

Cooperation between the EDA, OCCAR and NSPA

As discussed above, the EDA can support the acquisition lifecycle of a military product or capability, including procurement. OCCAR and NATO are mandated to do the same. However, there are possibilities for cooperation between them and each organisation has its own strength. An advantage of the EDA framework is the agency’s expertise in harmonising national requirements and translating them into cooperative solutions. The agency’s Steering Board, composed of defence ministers with the European Commission as a non-voting member, is also a unique asset. OCCAR, in turn, has extensive knowledge of the procurement of large armaments programmes, while NSPA brings the transatlantic dimension and a wealth of experience in managing and supporting diverse programmes (53).

An example of how joint European defence acquisition can work in practice is the MMF/MRTT fleet. The lack of air-to-air refuelling capabilities has long been recognised as a critical European shortfall. Consequently, a project was initiated in the EDA to requirements, a joint programme was prepared by the EDA at the request of Member States, which was then transferred ‘downstream’ to OCCAR in 2016 for the procurement phase with the first aircraft delivered in 2020 (54). A cooperation agreement between OCCAR and NSPA in turn, set the framework and conditions under which OCCAR managed the acquisition of the aircraft until the end of 2022, when responsibility for the programme was handed over to NSPA. Today, the MMF/MRTT fleet is operational with nine aircraft ordered and a tenth under contract (55).

Conclusion

Much criticism has been levelled at the slow pace of rearmament in Europe. Many argue that more European cooperation on defence acquisition would not only make buying arms and ammunition faster and cheaper, but also strengthen the European defence industrial base by consolidating demand. This Brief has reviewed the arguments for more collaboration on defence acquisition. While the track record is mixed, there may in fact be more armaments cooperation than is often believed and in many different forms. By acknowledging the variety of collaboration, focusing on the desired outcomes rather than processes, and using existing tools and structures, the EU and its Member States may be able to better collaborate on defence acquisition and arms procurement, where and how it makes most sense.

References

A draft of this Brief was presented to the EU National Armaments Directors and defence industry representatives at the EU High-Level Workshop on Armaments Cooperation, co-organised by the Swedish Defence Materiel Administration (FMV) and the European Defence Agency (EDA), under the auspices of the Swedish Presidency of the Council of the EU, in Brussels on 15 March 2023. The author thanks the participants for valuable comments and suggestions, and Clara Sophie Cramer for excellent research assistance as well as Christian Dietrich for his work on the graphics.

1. At the height of fighting in 2022, the Russian army was estimated to fire around 50 000-60 000 artillery rounds per day, and Ukraine 4 000-7 000. By December 2022, the United States had supplied Ukraine with more than 1 million artillery rounds while the EU Member States have sent another 350 000 155mm shells as of March 2023 and aim to deliver another 1 million rounds over the coming 12 months. See Gould, J., ‘Army plans “dramatic” ammo production boost as Ukraine drains stocks’, Defence News, 5 December 2022 (https://www.defensenews.com/ pentagon/2022/12/05/army-plans-dramatic-ammo-production-boost- as-ukraine-drains-stocks/); Barigazzi, J., ‘EU nears deal to restock Ukraine’s diminishing ammo supplies’, Politico, 15 March 2023 (https:// www.politico.eu/article/ukraine-war-european-union-ammunition- supplies-deal/); and Council of the EU, ‘Speeding up the delivery and joint procurement of ammunition for Ukraine’, 20 March 2023 (https:// www.consilium.europa.eu/media/63170/st07632-en23.pdf).

2. For a partial list, see Oliemans, J. and Mitzer, S., ‘Answering the call: heavy weaponry supplied to Ukraine’, Oryx, (https://www.oryxspioenkop.com/2022/04/answering-call-heavy-weaponry-supplied.html).

3. The ‘Collaborative Procurement of Ammunition’ project provides a seven-year framework for EU Member States and Norway to commonly procure multiple types and calibres of ammunition (5.56 mm to 155 mm) to replenish national stocks through the EDA. European Defence Agency, ‘EDA brings together 23 countries for Common Procurement of Ammunition’, 20 March 2023 (https://eda.europa.eu/news-and-events/ news/2023/03/20/eda-brings-together-18-countries-for-common- procurement-of-ammunition).

4. See, for example, a group of defence experts in ‘To face the Russian threat, Europeans need to spend together – not side by side,’ Euractiv, 19 April 2022 (https://www.euractiv.com/section/defence-and-security/ opinion/to-face-the-russian-threat-europeans-need-to-spend- together-not-side-by-side/).

5. Indicated in off-the-record discussions with national armaments officials from several Member States.

6. The figures do not include Denmark. Of the €52 billion, 82 % was spent on equipment and 18 % on R&D. See European Defence Agency, ‘EDA Defence Data 2020-2021’, 8 December 2022 (https://eda. europa.eu/publications-and-data/latest-publications/eda-defence- data-2020-2021).

7. Ibid., p. 10, Figure 7, ‘Defence equipment procurement expenditure and defence R&D expenditure (constant 2021 prices)’.

8. Ibid, p. 8, Figure 5, ‘Defence investment as % of total defence expenditure’, and p. 9, Figure 6, ‘Member States achieving the 20 % benchmark on defence investment in 2020 and 2021’.

9. Euronews, ‘EU countries to plug defence spending gaps with €70 billion by 2025’, 15 November 2022 (https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2022/11/15/eu-countries-to-plug-defence-spending-gaps-with- 70-billion-by-2035).

10. Reuters, ‘German lawmakers approve 100 billion euro military revamp’, 3 June 2022 (https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/german-lawmakers- approve-100-bln-euro-military-revamp-2022-06-03/).

11. See, for example, Euractiv, ‘Weapons industry booms as Eastern Europe arms Ukraine’, 24 November 2022 (https://www.euractiv.com/ section/global-europe/news/weapons-industry-booms-as-eastern-europe-arms-ukraine/); SAAB, ‘Saab year-end report 2022: Strong order intake and delivering on our outlook’, 10 February 2023 (https:// www.saab.com/newsroom/press-releases/2023/saab-year-end- report-2022-strong-order-intake-and-delivering-on-our-outlook); Rheinmetall Group, ‘Financial figures for 2022. Rheinmetall is on track for success: all-time earnings high, record order backlog’, 16 March 2023 (https://www.rheinmetall.com/en/media/news-watch/ news/2023/jan-mar/2023-03-16_rheinmetall-is-on-track-for- success-all-time-earnings-high,-record-order-backlog); Nexter,‘A record year for Caesar orders’, 13 January 2023 (https://www. nexter-group.fr/en/our-news/latest-news/record-year-caesar- orders); and Leonardo, ‘Integrated annual report 2022’, 9 March 2023 (https://www.leonardo.com/documents/15646808/0/Integrated+Ann ual+Report+2022+FINAL+%281%29.pdf/4e14dd1c-5124-dd71-f83d- 497e3cfdb11a?t=1679046722963).

12. Smith, R. Defence Acquisition and Procurement, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2022, p. 2.

13. NATO, ‘Funding NATO’, 12 January 2023 (https://www.nato.int/cps/en/ natohq/topics_67655.htm).

14. Pascal, F. et al., ‘Cooperation in defence and security procurement among EU Member States: applicable law and legal protection’, European Procurement & Public Private Partnership Law Review, Vol. 15, No 1, 2020, pp. 24–41.

15. See, for example, Darnis, J. P. et al., ‘Lessons learned from European defence equipment programmes’, Occasional Paper No 69, EUISS, 14 October 2007 (https://www.iss.europa.eu/content/lessons-learned- european-defence-equipment-programmes); European Commission and HR/VP for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, ‘Joint Communication on the defence investment gaps analysis and way forward’, JOIN(2022) 24 final, 18 May 2022 (https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2022-05/ join_2022_24_2_en_act_part1_v3_1.pdf).

16. See, for example, Besch, S., ‘EU defense and the war in Ukraine’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 21 December 2022 (https:// carnegieendowment.org/2022/12/21/eu-defense-and-war-in-ukraine- pub-88680).

17. See, for example, Heuninckx, B., ‘A primer to collaborative defence procurement in Europe: troubles, achievements and prospects’, Public Procurement Law Review, Vol 17, Issue 3, 2008; ‘Lessons learned from European defence equipment programmes’, op.cit.; and Lorell, M., ‘Multinational development of large aircraft. The European experience’, RAND Corporation, 1980 (https://www.rand.org/pubs/reports/R2596. html).

18. ‘Lessons learned from European defence equipment programmes’, op.cit.

19. Defence Acquisition and Procurement, op.cit, pp. 22-23.

20. For some examples, see ‘Multinational development of large aircraft. The European experience’, op.cit.

21. See, Kausal, T., A Comparison of the Defense Acquisition Systems of France, Great Britain, Germany, and the United States. Defense Systems Management College Press, Fort Belvoir, VA, 1999, p. iii (https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ ADA369794.pdf).

22. ‘Defence Data 2020-2021. Key findings and analysis’, op.cit.

23. Ibid.

24. To reach the 35 % European collaborative defence equipment procurement benchmark, Member States would need to collectively spend around €7 billion more. Whether the 12 Member States that did not provide data could have made up the gap, we do not know. See ibid., p. 15, Figure 12.

25. Some examples are given in the text but a more comprehensive list is being developed.

26. There are several other typologies for analysing armaments cooperation but this one is useful for capturing the nature of what we argue to be a way of quickly acquiring and procuring in parallel to minimise bureaucratic and legal risks.

27. See, for example, Andersson, J.J., ‘Pooling and sharing that works: The Heavy Airlift Wing at five’, EUISS Alert, 21 October 2014 (https://www. iss.europa.eu/content/pooling-and-sharing-works-heavy-airlift-wing- five).

28. In October 2022, France confirmed that it would design its future French mine warfare vessels on the basis of the binational Belgian-Dutch programme to maximise design communities and create opportunities for joint in-service support and other joint activity related to mine warfare capabilities. Machi, V., ‘France joins Belgian-Dutch designs for naval demining tech’, Defence News, 19 October 2022 (https://www. defensenews.com/global/europe/2022/10/19/france-joins-belgian- dutch-designs-for-naval-de-mining-tech/).

29. Global Defense Corp, ‘Norway signed agreement with Germany to buy six 212CD submarines’, 19 August 2021 (https://www.globaldefensecorp.com/2021/08/19/norway-signed-agreement-with-germany-to-buy-six- type-212cd-submarine/).

30. See, for example, Kincaid, B., Changing the Dinosaur’s Spots: The Battle to Reform UK Defence Acquisition. RUSI Books, London, 2008.

31. For example, the budget approval for the collaborative A400M transport aircraft programme took two years to pass the German Parliament and with Germany as the single largest buyer, all other partners had to wait. See, ‘Lessons learned from European defence equipment programmes’, op.cit.

32. Valpolini, P., ‘The Slovak MoD selects the CV90 as preferred bidder for its IFV programme’, European Defence Review (EDR on-line), 27 May 2022 (https://www.edrmagazine.eu/the-slovak-mod-selects-the-cv90-as- preferred-bidder-for-its-ifv-programme).

33. ‘Czech government authorises negotiations with Sweden on procurement of CV90 MkIV IFVs’, Janes, 22 July 2022 (https://www.janes.com/ defence-news/news-detail/czech-government-authorises-negotiations- with-sweden-on-procurement-of-cv90-mkiv-ifvs).

34. Europäische Sicherheit & Technik, ‘The Czech Republic and Slovakia procure and operate the CV 90 together’, 31 August 2022 (https://esut. de/en/2022/08/meldungen/36465/tschechien-und-die-slowakei- beschaffen-und-betreiben-den-cv-90-gemeinsam/).

35. Šiška, M., ‘Slovakia signed contract for 152 CV90 vehicles, Czech Republic to be the next CV90 user’, CZ Defence, 12 December 2022 (https://www. czdefence.com/article/slovakia-signs-contract-for-152-cv90-vehicles- czech-republic-to-be-the-next-cv90-user).

36. BAE Systems, ‘CV90: innovating by warfighters for warfighters’, 2 March 2020 (https://www.baesystems.com/en/article/cv90--innovating-by- warfighters-for-warfighters); and ‘IAV 2023: Ukraine to join CV90 user club’, Janes, 26 January 2023 (https://www.janes.com/defence-news/ news-detail/iav-2023-ukraine-to-join-cv90-user-club).

37. FMV, ‘FMV beställer bandvagnar i omfattande internationellt avtal’, 16 December 2022 (https://www.fmv.se/aktuellt--press/aktuella- handelser/fmv-bestaller-bandvagnar-i-omfattande-internationellt- avtal/).

38. FMV, ‘Sweden, Germany, United Kingdom jointly acquire 436 BAE Systems BvS10 all-terrain vehicles’, 16 December 2022 (https://www. baesystems.com/en-us/article/sweden-germany-united-kingdom- jointly-acquire-436-bae-systems-bvs10-all-terrain-vehicles).

39. Defense Brief, ‘The Netherlands sells GM200 MM/C multi-mission radars to Norwegian Army’, 25 May 2021 (https://defbrief.com/2021/05/25/the- netherlands-sells-gm200-mm-c-multi-mission-radars-to-norwegian- army/).

40. Naval News, ‘Denmark and the Netherlands sign MoU for joint procurement’, 16 December 2022 (https://www.navalnews.com/naval- news/2022/12/denmark-and-the-netherlands-sign-mou-for-joint- procurement/).

41. ERR News, ‘Estonian defense forces place order for Carl-Gustaf M4 anti- tank weapons’, 27 May 2020 (https://news.err.ee/1094930/estonian- defense-forces-place-order-for-carl-gustaf-m4-anti-tank-weapons).

42. SAAB, ‘Lithuania joins framework agreement on Carl-Gustaf’, 11 January 2022 (https://www.saab.com/newsroom/press-releases/2022/lithuania- joins-framework-agreement-on-carl-gustaf).

43. SeaWaves Press, ‘Finland & Sweden make joint purchase of 57MM ammunition’, December 2022 (https://seawaves.com/2022/12/01/finland- sweden-make-joint-purchase-of-57mm-ammunition/).

44. Andersson, J.J. ‘European defence partnerships: Stronger together’, Brief No 3, EUISS, 2 March 2023 (https://www.iss.europa.eu/content/ european-defence-partnerships).

45. NATO Support and Procurement Agency (NSPA) (https://www.nspa.nato. int/about).

46. OCCAR (https://www.occar.int/).

47. Article 42, paragraph 3 of the Treaty on European Union (consolidated version) (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A12008M042).

48. Ibid.

49. Council Decision (CFSP) 2015/1835 of 12 October 2015 on the statute, seat and rules of the EDA defines both tasks and tools underpinning the agency’s framework to foster cooperation among participating Member States (https://eda.europa.eu/docs/default-source/documents/eda- council-decision-2015-1835-dated-13-10-2015.pdf).

50. Following the EDA’s Effective Procurement Methods (EPM) initiative, the agency signed in 2014 a multi-annual framework agreement with SAAB for the provision of different types of ammunition for the ‘Carl-Gustaf’ anti-tank weapon system under a 2013 procurement arrangement between the EDA and Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, the Czech Republic,and Poland. See, European Defence Agency, ‘EDA signs a framework agreement to provide Carl-Gustaf ammunition for its Member States’, 8 July 2014 (https://eda.europa.eu/news-and-events/news/2014/07/08/ eda-signs-a-framework-agreement-to-provide-carl-gustaf- ammunition-for-its-member-states).

51. European Defence Agency, ‘Collaborative procurement of ammunition’, 20 March 2023 (https://eda.europa.eu/news-and-events/ news/2023/03/20/eda-brings-together-18-countries-for-common- procurement-of-ammunition).

52. Ibid.

53. The EDA and OCCAR signed an Administrative Arrangement in 2012. OCCAR and NSPA have an MoU since 2005 and a Security Agreement since 2009. See OCCAR, ‘Our partner organisations’ (https://www.occar. int/partners).

54. European Defence Agency, ‘Multinational Multi-Role Tanker Transport Fleet (MMF) takes shape’, 28 July 2016 (https://eda.europa.eu/news- and-events/news/2016/07/28/multinational-multi-role-tanker- transport-fleet-(mmf)-takes-shape).

55. OCCAR, ‘Farewell MMF Programme Division – job well done!’, 20 December 2022 (https://www.occar.int/farewell-mmf-programme- division-job-well-done?redirect=/news%3Fpage%3D2%23news).