You are here

After Nagorno-Karabakh

Introduction

The longstanding conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh ended with the capitulation of the breakaway republic to Azerbaijani forces in September. Almost the entire Karabakh population (120 000) fled their homes to seek sanctuary in Armenia. Yet peace between Azerbaijan and Armenia is not in sight. The EU should pursue deeper strategic engagement in the altered geopolitical landscape in the South Caucasus. The costs of inaction are yet more violence and instability in the EU’s neighbourhood, and Moscow managing to lock the region into a cycle of chaos and conflict that it would exploit in an effort to salvage its declining hegemony and evade Western sanctions.

A broader conflict unresolved

The bitter and protracted Nagorno-Karabakh conflict was rooted in competing claims to territory inscribed with collective memories of historical statehood in Armenia and Azerbaijan. The conflict flared up periodically over the last century whenever Moscow was weakened or distracted by other events. Now it is over, but the risk of further hostilities between the two states remains high.

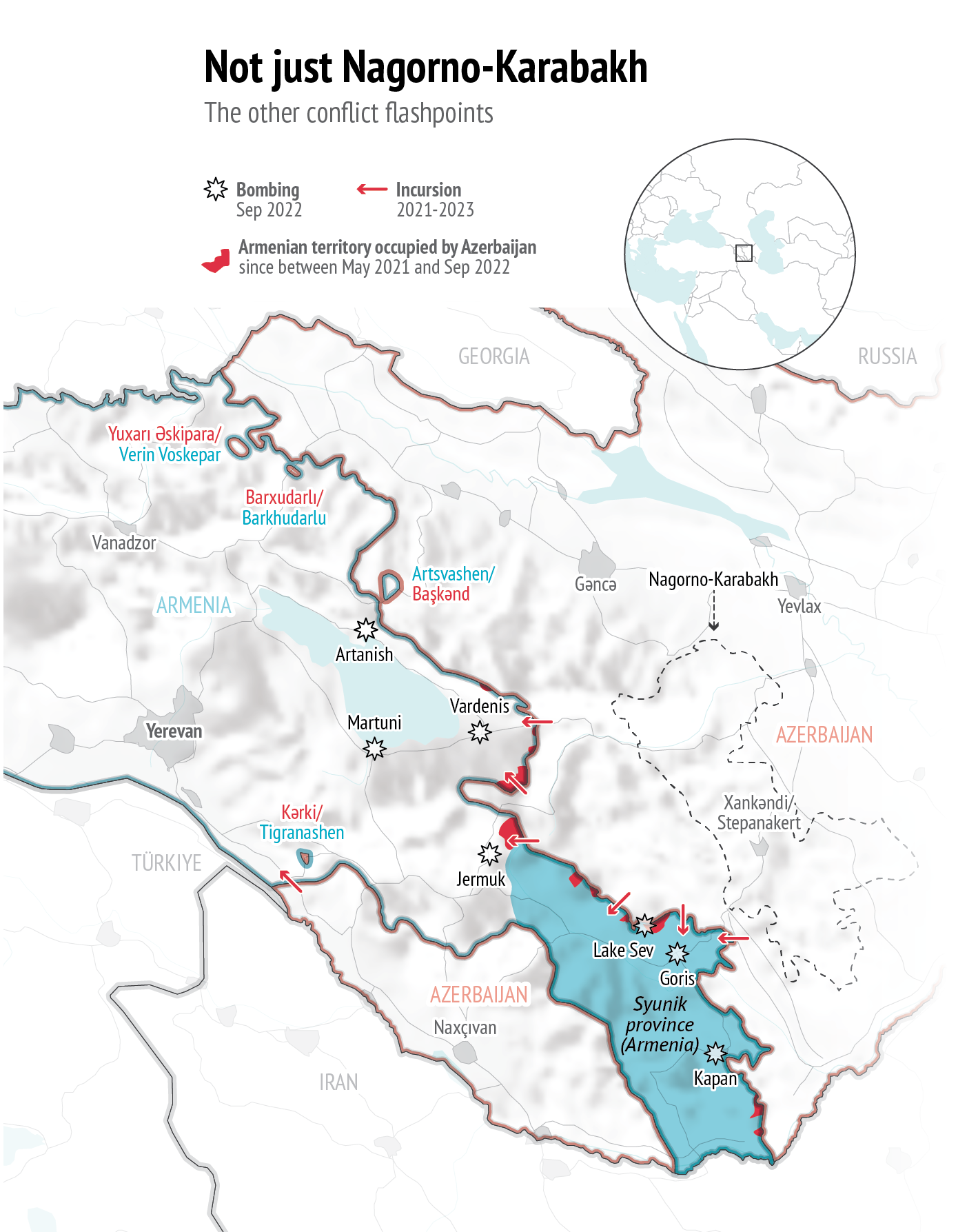

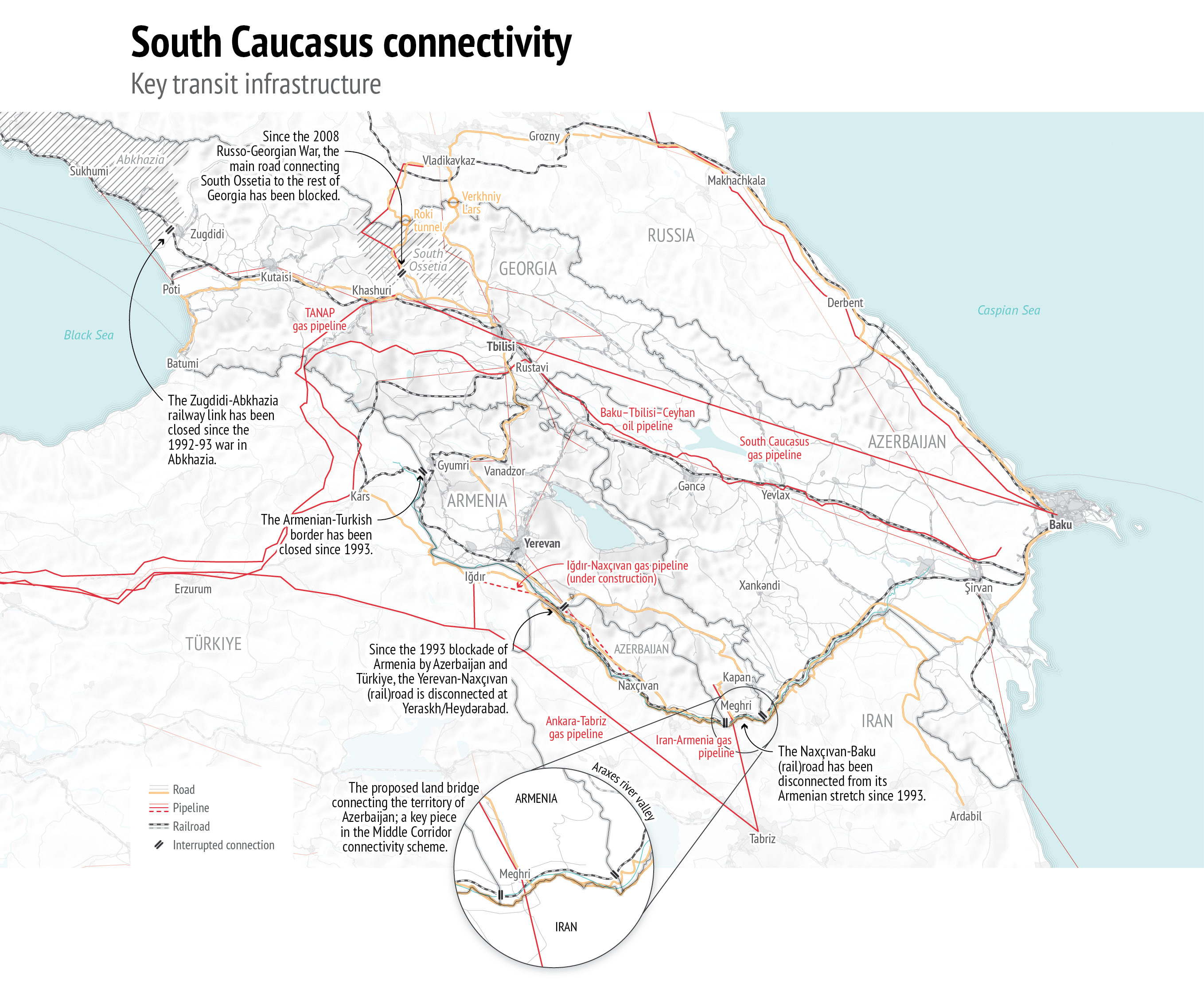

The current focus of the conflict has shifted to Armenia’s Syunik province. Like Nagorno-Karabakh, Syunik, also referred to by Baku (and Ankara) as ‘Zangezur’, an imprecise toponym of Turkish origin, is a historically contested territory. Unlike Nagorno-Karabakh, Syunik matters to Baku as a land bridge from Azerbaijan proper to Naxçıvan which borders Türkiye. A modern road and railway connection that would pass through Syunik would also be a key link in the ‘Middle Corridor’ east/west connectivity scheme, as an alternative to northern Eurasian and southern sea routes – in particular if the border between Armenia and Türkiye reopens in parallel.

Azerbaijan, backed by Türkiye, insists that the ‘Zangezur corridor’ in Syunik must be opened as soon as possible. Armenia is ready in principle to acquiesce but it firmly rejects Azerbaijan’s idea that the corridor should be ‘extraterritorial’ – removed from Armenia’s sovereign jurisdiction. It also objects to the idea that Russian border guards (FSB), already present in Syunik, should exercise control over transport links if the corridor becomes operational.

Data: Natural Earth, 2023; European Commission, GISCO, 2023

There is no fundamental incompatibility of interest regarding the transport connections. But in view of the history of recent military operations against Armenia (that have taken place since 2021) and threats to ‘take Zangezur by force if necessary’ (1), there remains a distinct risk that Azerbaijan may seek to occupy Syunik. A less likely ‘hot conflict scenario’ would see Russia seeking to spoil a future agreement by supporting a limited incursion by Azerbaijan. Moscow would see this as a means of bringing Armenia back to the fold, and further discrediting prime minister Nikol Pashinyan for causing relations with Russia to deteriorate to their current low level.

The shifting sands of regional geopolitics

The South Caucasus is a fraught and contested geopolitical landscape. Russia’s ability to influence developments in the region is weakening. Instead of stepping in to prevent Azerbaijan from taking Nagorno-Karabakh by force – and even from bombing and undertaking incursions into the territory of its longstanding ally, Armenia – Moscow opportunistically chose not to intervene for reasons of political calculus. This marked a paradigm change in Moscow’s involvement in ethnopolitical conflicts in its former peripheries. It traditionally sided with the separatists to weaken, or at least exercise leverage over, the newly independent states.

Moscow also proved unable to prevent a democratic transition in yet another country (after Georgia and Moldova) where it had previously sought to exploit ethnic and political divisions. The new political elite in Armenia insisted that their revolution was not about geopolitics. The sense that its traditional protector is increasingly unreliable, however, has led Yerevan to cautiously look more to the West (2).

Data: Natural Earth, 2023; European Commission, GISCO, 2023; Global Energy Monitor, 2023

To counter the erosion of its hegemonic power, Moscow relies on a hybrid combination of diplomatic and economic pressure and disinformation and malign influence operations to destabilise the government. It also seeks to promote connectivity through the ‘Zangezur corridor’ on its terms – that is, with the corridor under the FSB’s control. At stake is the consolidation of Russia’s regional position and its strategy of developing ‘alternative’ trade routes via the Iranian Persian Gulf to circumvent Western sanctions.

While Russia’s power to direct events in its former periphery declines, Türkiye’s influence through diplomatic and military support to Azerbaijan is on the rise. It sees increased trade flows in the Middle Corridor, to which the opening up of a ‘Zangezur corridor’ is key (3), as reinforcing its geopolitical position in the region. It is therefore conceivable that Ankara’s interests may be sufficiently aligned with those of the EU with regards to removing existing barriers to the movement of goods. Now that Baku’s control over Nagorno-Karabakh has been restored, the country’s ruling elite, with which President Erdogan maintains strong personal and business ties, no longer needs to be pressurised to accept any compromise solution over the territory, which should make such alignment easier.

Three pillars of the EU's strategic engagement

The geopolitical stakes in scripting the future of the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan are high. The EU’s strategic engagement should rest on three main pillars.

First, the EU, including its Member States, must seek to credibly deter a future military offensive against Armenia. To do so, it should signal its readiness to reduce, and possibly even halt, oil and gas imports from Azerbaijan – together with other steps that the Commission can take even without unanimity among the Member States, such as suspending the implementation of the Economic and Investment Plan as well as the visa facilitation agreement with Baku.

This should be based on a realistic assessment of the importance of Azerbaijani hydrocarbon imports to the EU’s diversification efforts. In 2022, supplies from Azerbaijan accounted for 3 % of the EU’s gas consumption and with Azerbaijani gas exports to Europe expected to reach 12 bcm in 2023 Baku is foreseen to deliver the same share this year. This is three times less than the gas imported by pipelines from North Africa (37 bcm), and seven times less than the volume supplied by Norway (88 bcm) (4). Even if Azerbaijan were to manage to supply 20 bcm per annum in 2027 – an unlikely prospect given insufficient capacity, infrastructure and investment (5) – it would not be a game changer. The EU, on the other hand, is Azerbaijan’s most important trading partner.

Second, the EU should seek to help Armenia overcome its current security deficit, boost economic development and support the pursuit of an independent foreign policy. The EU Mission in Armenia (EUMA) should be equipped with more staff and resources as soon as possible. With some Member States providing Armenia with military assistance bilaterally – France now notably supplying air defence components and committing to train Armenian troops – the EU as a whole can step up its engagement as a regional security actor as Russia’s traditional protective role wanes. The EU ought to make Armenia the fourth Eastern Partnership country to receive European Peace Facility (EPF) assistance. It should support Armenia’s democratic resilience as a means of enabling the country to make sovereign political choices – a right currently denied to Yerevan by Moscow (6). A new partnership mission could be established in Armenia with a focus on countering foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI). Resilience programmes under the Eastern Partnership policy framework should be boosted to provide a necessary longer term, structural complement.

The EU would do well to ramp up investment in the country’s economic development. This would increase competitiveness and reduce Armenia’s currently significant dependency on Russia (7). The Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement (CEPA) should be upgraded to an association agreement including a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA). The EU should pursue the idea of negotiating a visa liberalisation agreement, as a gesture of openness and goodwill, and even indicate its readiness to grant Armenia a European accession perspective.

Third, the EU should facilitate the negotiation of a comprehensive peace treaty that would create structural conditions for future peace. The treaty should set out steps for the normalisation of mutual relations. It should also clear the path towards future regional connectivity that would benefit Armenia, Azerbaijan, Türkiye and the EU. Speed is of the essence in this endeavour, and the treaty should thus take the form of a basic framework agreement. Details can be refined and elaborated at a later stage.

The key elements of the future connectivity project would be the construction of a new road and the restoration of the approximately 45 km of railway line connecting Azerbaijan and Naxçıvan through Syunik. The ‘corridor’ would remain under Armenia’s sovereign jurisdiction but with a new international presence established. The European Investment Bank (EIB) could provide funding for these infrastructure projects. The Kars-Yerevan railroad would also be rebuilt – finally normalising relations between Türkiye and Armenia. This would complete the regional section of the Middle Corridor, in which Türkiye has heavily invested, and deliver economic benefits for both Armenia and Azerbaijan while reducing the former’s dependence on Russia. Finally, Armenia should be included in the Black Sea Cable project and get more support to accelerate renewable energy production provided it does its own homework on both these undertakings.

In return for this investment on the EU’s part, Armenia and Azerbaijan should agree to withdraw their respective military forces from the border, show goodwill in bilateral negotiations on delimitation and demarcation, and participate in confidence-building mechanisms facilitated by EUMA. Armenia should make a legally binding commitment not to lay claim to Nagorno-Karabakh in the future. Azerbaijan, for its part, should discard its revisionist rhetoric – for more than a decade now, President Aliyev has referred to Armenia from time to time as ‘Western Azerbaijan’.

The European negotiating track is the only one that can deliver on changing basic conditions to achieve peace through connectivity. The EU alone has the ability to steer this process. It should direct its economic and diplomatic resources to connect all the necessary dots to reach an agreement on fundamental principles in a timely manner – a task that is clearly beyond Russia as it struggles to come to terms with its declining hegemony.

References

* The author is grateful to Pelle Smits for his indispensable research assistance.

1. Ilham Aliyev’s interview with Azerbaijan television, 20 April 2021 (https://president.az/en/articles/view/51216).

2. See for example Gavin, G., ‘We can’t rely on Russia to protect us anymore, Armenian PM says,’ Politico, 13 September 2023 (https://www. politico.eu/article/we-cant-rely-russia-protect-us-anymore-nikol- pashinyan-armenia-pm/); European Parliament, ‘Armenian Prime Minister; /”We must move steadily towards peace with Azerbaijan”’, Press Release, 17 October 2023 (https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/ en/press-room/20231013IPR07127/armenian-prime-minister-we-must-move-steadily-towards-peace-with-azerbaijan). In addition to these and similar statements, Pashinyan’s government has effectively suspended representation in the CSTO and participation in joint exercises.

3. See for example the ‘Shusha Declaration’, 16 June 2021 (https:// president.az/en/articles/view/52122).

4. International Energy Agency, ‘Baseline European Union gas demand and supply in 2023’ (https://www.iea.org/reports/how-to-avoid-gas- shortages-in-the-european-union-in-2023/baseline-european-union- gas-demand-and-supply-in-2023).

5. Economist Intelligence Unit, ‘Azerbaijan’s gas exports to the EU face challenges,’ 10 July 2023 (https://www.eiu.com/n/azerbaijans-gas- exports-to-the-eu-face-challenges/).

6. ‘Russia is an integral part [неотъемлемой частью] of this region and so cannot leave. It cannot leave [покинуть] Armenia,’ in the words of the Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov. ‘Армения разворачивается на Запад?‘ [Is Armenia turning to the West?], Echo Kavkaza, 6 September 2023 (https://www.ekhokavkaza.com/a/32581310.html).

7. Nazaretyan,H., ‘Armenia’s economic dependence on Russia: How deep does it go?’ EVN, 7 July 2023 (https://evnreport.com/economy/armenias- economic-dependence-on-russia-how-deep-does-it-go/).