You are here

Walking a tightrope

Introduction

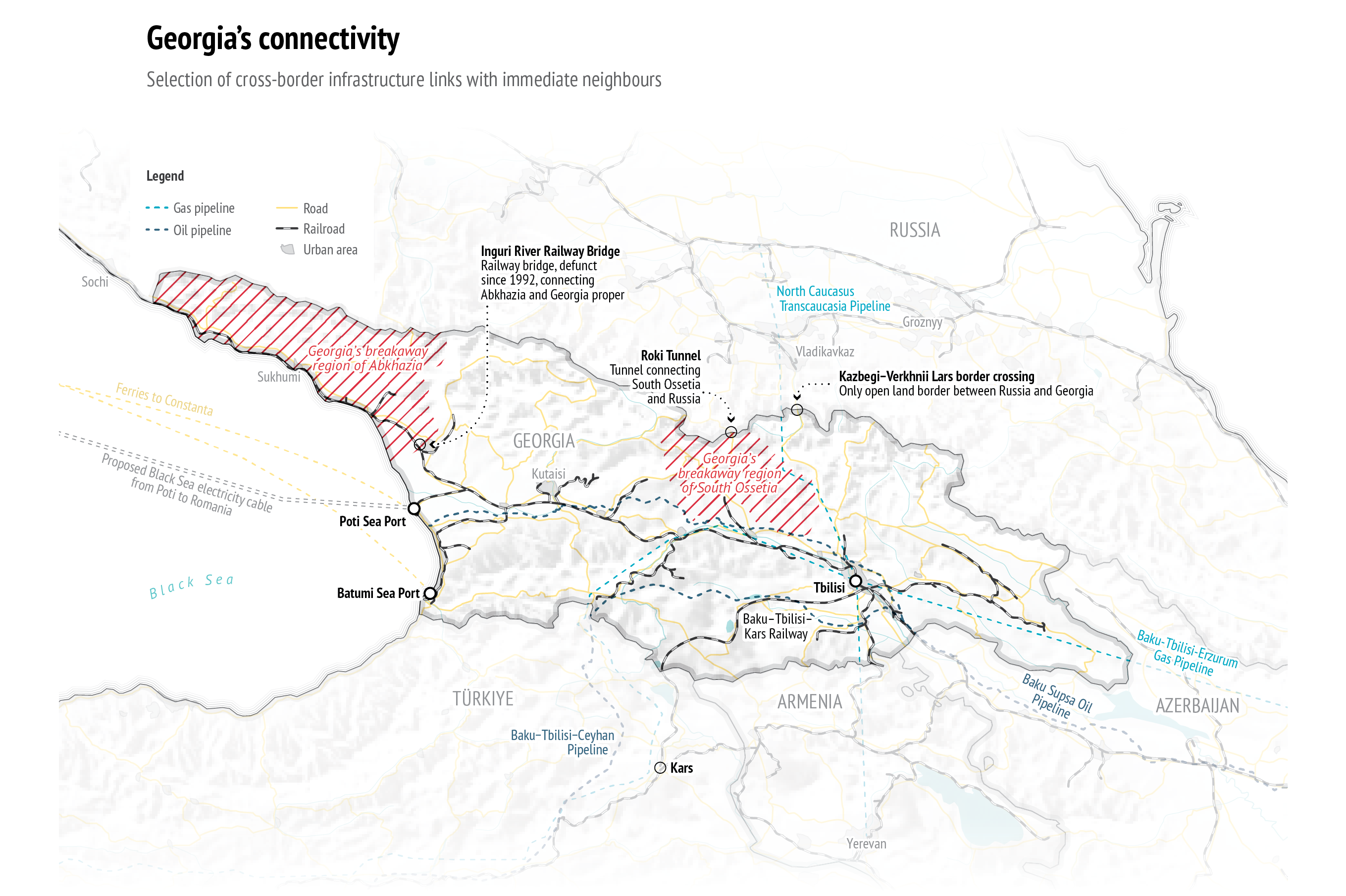

What happens to Georgia matters for the EU. Georgia’s strategic location at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, along with its potential to serve as a transit hub for oil and gas from the Caspian Sea to Europe, makes it a key player in the EU’s energy security and economic connectivity. Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine has further increased Georgia’s importance in this regard.

Despite having an institutionally strong relationship with the EU through a comprehensive Association Agreement and a promise of EU membership, recent mounting concerns over the state of democracy and politics in Georgia pose a risk to its integration into the EU.

This Brief aims to explore how both domestic and external factors influence Georgia’s course towards EU integration and the obstacles on this path. The first section highlights key trends in Georgian politics, while the second section discusses the impact of Russia’s war against Ukraine on Georgia. The third section explores how these factors affect Georgia’s EU integration prospects, and the final section offers some practical recommendations.

Deciphering political trends in Georgia

Over the past several years, Georgia has become an increasingly unpredictable and difficult partner for the EU. This is mainly due to the deeply polarised domestic political environment, reflected in mass protests regularly met by government crackdowns, which have not only exposed the inherent weaknesses of Georgia’s political and electoral system, but also tarnished its image within the EU.

A key issue often overlooked when examining Georgian politics is the legitimacy crisis faced both by its leadership and by its main political parties. In addition to lacking public support – with 64 % of Georgians expressing the belief that none of the parties represent their interests (1) – the country’s main political parties suffer from problems of internal legitimacy, reflected in two primary interrelated trends: the growing personalisation of Georgian politics, and the deficit of internal democracy.

The prevailing perception is that the country’s ex-prime minister, the oligarch Bidzina Ivanishvili, exerts significant influence over Georgia’s ruling party, Georgian Dream (GD) (2), while the main opposition party, the United National Movement (UNM), is suspected of being controlled by former high-ranking officials (3). This means that informal governance networks play a prominent role in Georgian politics, hindering the institutionalisation of political parties and leading to a lack of accountability and internal democratic mechanisms within their structures.

Another worrying trend in Georgia’s politics is the parties’ inability to achieve any lasting agreement or compromise. A ‘winner takes all’ mentality, fostered by a highly personalised political culture and the long-standing tradition of a mixed/majoritarian electoral system in the country, discourages parties from engaging in efforts at constructive collaboration. While it might be assumed that this absence of a culture of compromise and cooperation stems from differing ideological views, as is common in many political systems, this is not the case in Georgia. The country’s politics primarily revolves around personalities rather than ideologies.

The failure of political actors to engage in productive dialogue often leads to boycotts and street demonstrations being used as tools to exert political pressure. Due to the limited space for political participation, achieving significant progress in political negotiations has become increasingly reliant on massive civic protests. One notable example is the decision to switch to a fully proportional system, which followed the violent ‘Gavrilov night’ protests outside the Georgian parliament in June 2019. The mass protests erupted after Russian Duma Communist deputy Sergei Gavrilov presumptuously sat in the chair of the Speaker of the Georgian Parliament during the Inter-Parliamentary Assembly on Orthodoxy (IAO), creating a furore among the opposition.

The prevalence of boycotting and street demonstrations has made any political negotiations contingent on international mediation efforts. Over the past three challenging years, no agreement has been reached between opposing political parties without the decisive involvement of international actors or mediators. So, in an unprecedented move within the history of the Eastern Partnership, the President of the European Council initiated dialogue with political parties after eight of them refused to recognise the election results. This mediation led to the ‘Michel Document’ (4), an agreement reached on 19 April 2021, which included commitments to significant electoral and judicial reforms, power-sharing in parliament, and ending politically motivated prosecutions.

Although the ruling GD party signed the document, the major opposition party, UNM, refused to do so, citing ambiguity regarding the issue of political prisoners, even though actually observing the agreed principles - thus underscoring that reducing existing polarisation was not on the agenda of the parties involved. However, the GD used this as a convenient pretext when announcing its unilateral withdrawal from the agreement a few months later.

Georgia’s politics primarily revolves around personalities rather than ideologies.

Intense personal animosities among the key political figures drives the polarisation that dominates the political arena in Georgia, best characterised as artificially created by the elites rather than by ordinary citizens. Ordinary Georgians are preoccupied first and foremost with unrelenting social hardship as one in every two Georgians feels economically insecure (5). Not surprisingly, the chances of reducing the sharp polarisation within the political elite were further diminished by the clandestine return of Georgia’s former president, Mikheil Saakashvili, after eight years of self-imposed exile. Saakashvili hoped for a triumphant comeback, intending to mobilise his supporters before the local elections in October 2021. Instead, Georgian law enforcement agencies arrested him. In addition to being charged with illegally crossing the border, Saakashvili had already been convicted and sentenced (in absentia) to a total of nine years in prison for abusing his authority in two separate cases. While he denies any wrongdoing and describes the sentences as politically motivated, his health is reportedly deteriorating in prison amid allegations of inhumane treatment (6).

The media’s role in exacerbating the trend towards polarisation in Georgia should also be noted. Although media freedom in Georgia has generally deteriorated (7), the country’s media landscape faces greater challenges. This is because major media outlets, instead of addressing the actual concerns of the Georgian people, have become instruments of political partisanship and manipulation, contributing to societal division (8). A media monitoring report released by the UNDP highlights a worrying trend of deep partisan divisions between media camps (9). One major issue of dissent revolves around Georgia’s external policies, specifically regarding its attitude and actions in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and the direction and consistency of respective government policies.

Georgia's 2023 electoral scenarios

Georgia is gearing up for parliamentary elections in 2024, which are expected to usher in a new political landscape in the country. The fully proportional electoral system may lead to more equitable and balanced political representation, creating the possibility of forming a coalition government and promoting compromise and power-sharing among political actors.

Yet, despite the ruling Georgian Dream party’s leadership – in both its formal and informal manifestations – being increasingly unpopular, no viable alternative has emerged as yet. The main opposition, UNM, has struggled to gain support from at least a third of the electorate, and has been unable to shake off the public memory of its past mistakes. However, while it is improbable that the GD will secure a supermajority through the fully proportional vote, the type of coalition that comes to power will have a significant impact on whether the weakened GD is restricted and counterbalanced in its policies by coalition partners. However, external or internal events, or serious mistakes by the GD leadership, may bring new political alternatives to the forefront, although the timeframe may not be conducive to immediate change. Still, any such change will probably lead to more balanced, responsible, pro-Western policies and a better quality of governance. Despite the anticipated change in the GD leadership, it is expected that until the elite undergoes a fundamental shake-up, vendetta-style relations between opposing political forces and the vicious circle of political polarisation will persist for quite a while albeit in a somewhat milder form.

Cultivating ambiguity over the war in Ukraine

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has profoundly ruptured its relations with Western countries. However, with regard to Georgia’s relations with Russia, not much has changed since the softening of anti-Russia rhetoric on the part of the GD government after it came to power in 2012. Despite the strong pro-Ukrainian public stance, the fact that several hundred Georgians (10) are fighting in Ukraine against Russian forces (which is the largest number of volunteers coming from any of the other countries in the region), and Georgia’s official declarations of support for the Ukrainian cause, including in United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) votes, the government’s overall reaction to the Russian invasion of Ukraine has been muted and rather unassertive.

Georgia abstained from implementing most of the international sanctions targeting Russia and has not assisted Ukraine by providing military aid despite Kyiv’s repeated requests. The Georgian prime minister argued that sanctions are ‘ineffective’ and harmful to the country’s economic and security interests. Still, despite Tbilisi’s reluctance to join EU sanctions on Russia, Georgia has sent more than 400 tonnes of humanitarian aid (11) to Ukraine, hosted approximately 24 000 Ukrainian refugees (12), and sent 25 power generators to the country (13) (as of July 2023).

Data: Global Energy Monitor, 2022; European Commission, GISCO, 2023; Natural Earth, 2023

In response to Georgia’s non-committal attitude, a disgruntled Ukraine has recalled its ambassador, while calling Georgia’s position ‘immoral’ amid an escalating war of words. Considering the previous level of strategic partnership between Ukraine and Georgia in the format of the EU’s Associated Trio (Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine), relations between Kyiv and Tbilisi were already tense due to the imprisonment of Saakashvili, now a Ukrainian citizen, who has held various positions in Kyiv together with some members of his former team, while Tbilisi had officially requested his extradition to Georgia.

While Moscow has hailed Tbilisi’s ‘balanced’ stance on Russia sanctions (14), Ukrainian Defence Intelligence has accused Georgia of helping Russia in circumventing Western sanctions, an accusation that has also been echoed by some media personalities (15). The Georgian authorities have repeatedly denied these accusations, and although there has not been any reliable factual evidence of this happening, the allegations have further damaged Georgian-Ukrainian relations.

Notably, the statements and rhetoric by the Georgian President – Salome Zourabichvili – sharply contrasted with the government’s lukewarm and often ambiguous position by expressing solidarity with anti-Russian demonstrators in Georgia, who were demanding a more robust response to the war in Ukraine (16).

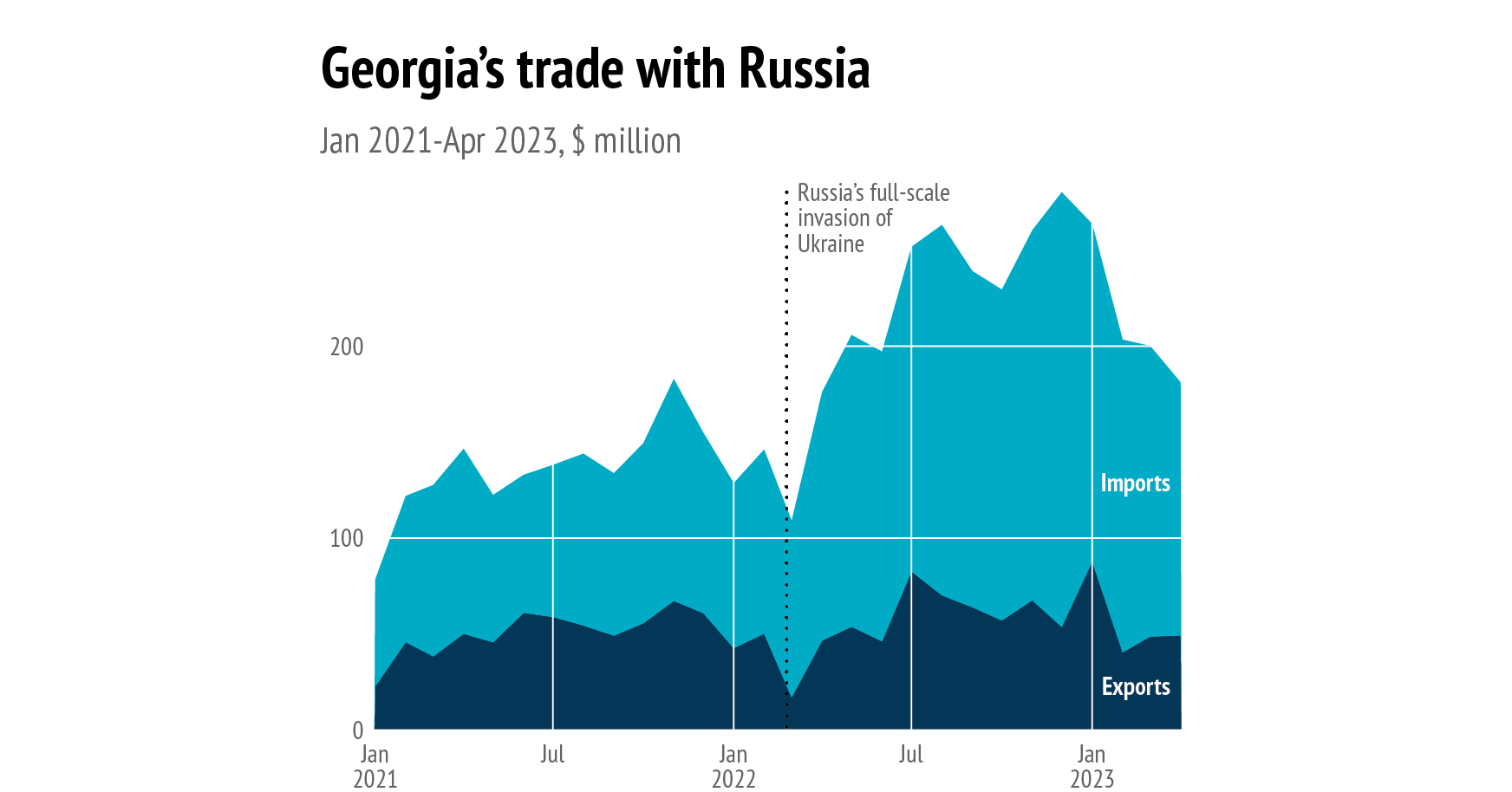

Economically, Georgia has experienced somewhat unexpected consequences from the current situation due to a number of factors. Georgia’s trade with and hence economic dependency on Russia has increased due to growth in trade with its larger neighbour (17). Georgia has also emerged as a ‘safe haven’ or transit stopover for more than a million Russians (just for March – November 2022 (18)) who have fled the country in order to escape mounting repression and/or the risk of mobilisation, or just increasing economic hardship. This influx of migrants brought in total about USD 2.7 billion worth of financial inflows into the country in 2022-2023, strengthening the local currency and also leading to rocketing real estate and consumer prices. In 2022, the number of companies registered by Russian citizens in Georgia increased significantly as compared to 2021 (19).

Thus, while Western countries are trying to decouple their economies from Russian imports of raw materials and energy, in the case of Georgia, trade with Russia is growing, while Russians enjoy visa-free entry to Georgia and can reside in the country for up to one year. The warming of relations between Moscow and Tbilisi is further demonstrated by Russia’s recent decision to restore visa-free travel for Georgian citizens and lift the ban on direct flights between the two countries (20).

It is worth noting that even before ‘partial’ mobilisation in Russia and the dramatic increase in the inflow of Russian migrants, public opinion polls suggested that up to two thirds of the Georgian population favour the introduction of a visa regime for Russian citizens. For, while the migratory and financial influx has had a positive effect on Georgia’s GDP, which has registered annual growth of 11 % (21), the wider population and disadvantaged social groups have suffered.

Russian immigration also entails significant risks for Georgia’s national security in a number of ways, as the high concentration of Russians creates fertile ground for Russian propaganda and disinformation, or the less probable but still possible risk of a confrontation between the Ukrainian and Russian population groups. Furthermore, if a substantial number of Russians were to be naturalised in Georgia, they could emerge as a significant electoral or political force within the country, influencing policy decisions in unpredictable ways.

How will Russia's military defeat or success affect Georgia?

There are also many unknowns regarding the geopolitical environment linked to the war in Ukraine that may have significant repercussions for Georgia. Any outcome of the war including its further perpetuation will have an impact on Georgia’s security situation but also on its relations with relevant major players including first and foremost the EU, the United States and Russia.

If Russia achieves military success in Ukraine, Georgia may face dangerous pressure to align more closely with Russia’s political and economic interests, potentially jeopardising Tbilisi’s aspirations for closer ties with the EU and NATO. Furthermore, Russia’s success could embolden it to intervene more aggressively and openly in the frozen conflicts in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, which are under Russian control. Russia will also ramp up its efforts to undermine Georgia’s democratic institutions and civil society through disinformation campaigns and other hybrid warfare tactics. The influence of pro-Russian political parties and networks in Georgia could further increase both within and outside the government, potentially leading to a ‘normalisation’ of relations with Russia. This would likely result in a decreased focus on strengthening the country’s sovereignty and democracy, or on restoring territorial integrity.

History has taught Georgians that, whether weakened or strengthened, Russia remains an existential threat.

On the other hand, a weakened Russia could provide Georgia with an opportunity to assert its sovereignty and strengthen its ties with the West without fear of Russian retaliation. The pro-Western opposition parties would likely gain more ground and popularity while significantly increasing their chances of scoring highly in the upcoming 2024 parliamentary elections. However, a weakened Russia may also feel compelled to act aggressively to regain the public support of the government (provided that no drastic changes occur, putting Georgia at a heightened security risk). Georgia could become an easy target for Russia to reassert its influence through various means, such as supporting separatist movements, launching cyberattacks, or initiating other destabilising activities.

While it is broadly expected that the war will not end any time soon, the climate of uncertainty may also influence the strategies of internal political forces in Georgia and its geopolitical environment, although in less predictable ways. While there is little expectation that in the long term Russia will regain its power and hegemony over its ‘near abroad’, history has taught Georgians that whether weakened or strengthened, Russia remains an existential threat, unless Georgia joins the West and obtains some reliable security guarantees.

Georgia's rocky road to the EU

Even before the war in Ukraine started, increased turbulence in Georgia’s domestic politics, coupled with a certain regression in the state of democracy in the country, had strained Tbilisi’s relations with the EU. This was reflected in several incidents, such as alleged spying on EU diplomats (22), accusations against the former EU Ambassador to Georgia over his excessive involvement in domestic political affairs (23), the Georgian parliament’s failure to engage in launching the EU’s Jean Monnet Dialogue (24), as well as a variety of other similar episodes. All of this has called into question whether the Georgian government’s declared intention to accelerate EU accession is totally genuine. As the German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock stated in mid-March 2023, just before visiting Georgia: ‘We see attempts to steer Georgia away from the pro-European course and the pressure it faces from inside and outside’ (25).

According to the Association Implementation Report on Georgia, released by the European External Action Service in August 2022: ‘In 2021, Georgia’s alignment rate with relevant High Representative statements on behalf of the EU and Council Decisions was 53 %, marking a decrease from 62 % in 2020. During the first half of 2022, the rate further decreased to 42 %’ (26).

Moreover, aggressive attacks by leading Georgian politicians against MEPs or European diplomats who had voiced criticism of Georgia’s stance (27), as well as the narrative that the West is dragging Georgia into the war with the intention of opening a second front with Russia, have caused a certain amount of diplomatic embarrassment. Finally, the Georgian government’s most recent (abortive) endeavour to adopt the Russian-inspired ‘foreign agents’ law in March 2023, which triggered massive street protests and attracted global condemnation, led to a firm response from the EU as well. The bill would have required non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and independent media outlets that receive more than 20 % of their funding from abroad to formally declare themselves as foreign agents. If passed, the law would have created an instrument that could have been used to limit press freedom and suppress civil society, as was the case in Russia. Commenting on the law, HR/VP Josep Borrell noted that the bill’s final adoption would have had ‘serious repercussions’ for EU-Georgia relations (28). Massive street protests led by young people coupled with international pressure forced GD to withdraw the bill.

In June 2022 the EU recognised Georgia’s membership perspective without granting the country candidate status, following the European Commission’s assessment of Georgia’s application. The Georgian government initially intended to apply for EU membership in 2024 as indicated in the ruling party’s electoral programme (29). But Ukraine’s application for fast-tracked EU membership on the one hand, and the pressure from Georgia’s vibrant civil society on the other, influenced the Georgian government’s decision to advance the country’s membership bid. Yet it is worth noting that despite Ukraine’s initiative, the Georgian government initially seemed confused and uncertain whether or not to follow suit. However, Moldova’s EU membership application finally made Tbilisi realise that there was significant geopolitical momentum that could have been Georgia’s sole window of opportunity to finally embark on the EU enlargement process. On 3 March 2022, the GD announced that Georgia would apply for EU membership (30).

Notably, the fact that the EU membership applications of the participants of the newly formed ‘EU Association Trio’ were uncoordinated and submitted separately demonstrated the serious political shortcomings of this platform, despite its obvious strategic relevance. This initiative was formally signed into being by the Georgian, Moldovan and Ukrainian governments in 2021 with a view to strengthening trilateral cooperation and coordination and aiming to accelerate the movement of these countries toward EU membership. Yet, today the chances of it realising its full potential seem dim. Both Ukraine and Moldova have been trying to distance themselves from Georgia, which seems to be backtracking on its democratisation path. Georgia’s apparent disinterest in developing bilateral and trilateral sub-formats of cooperation, coupled with the country’s tepid response to Russia’s actions in Ukraine, as well as the Georgian government’s alleged ill-treatment of the imprisoned Saakashvili, created additional cracks within the trilateral format (31).

Despite the absence of formal candidacy status, the importance of granting an EU membership perspective to Georgia should not be underestimated – it is undoubtedly a significant achievement for the country. While the term ‘enlargement/European perspective’ is not legally defined by EU law, it does refer to an acknowledgment of potential membership, indicating a greater likelihood of eventually attaining it.

The EU’s decision to defer Georgia’s candidacy status drew an angry reaction from Tbilisi, which maintained that the real reason for Brussels’ decision was Georgia’s refusal to demonstrate stronger engagement with the EU’s position on the war in Ukraine by fully signing up to sanctions against Russia (32). However, there has been a sharp contrast between the government’s rhetoric and public reaction. Thousands of people took to the streets protesting against the Georgian government’s insufficient efforts to advance with fulfilling EU requirements in order to achieve candidate status (33).

The EU argued that Georgia was riven by political polarisation and had not demonstrated sufficient progress in making the judiciary genuinely independent, in addressing high-level corruption cases, and in its efforts to ‘de-oligarchise’ the state, as well as in guaranteeing a free, pluralistic and independent media environment, and ensuring the involvement of civil society in decision-making processes. Granting the country candidate status was therefore made conditional on the implementation by the government of twelve reform priorities. These conditions, known as the twelve recommendations (34), remain the key milestones to be met by Georgia’s political leaders.

The country’s backtracking within the democratic sphere has been mainly reflected in the lack of progress in the core areas of judicial and media reforms which the EU considers fundamental for EU accession. The EU’s Annual Report (35) on Georgia for 2022 notes that a number of crucial laws (e.g. on the functioning of the judiciary, key appointment procedures, legal procedures for covert surveillance, and the dissolution of the State Inspector’s Service) were rushed through parliament without the necessary analysis of compliance with EU or Council of Europe standards. The report highlights a number of politically ‘sensitive’ court cases, inferring that there may have been political interference in judicial proceedings.

Looking ahead

Already at the end of 2023 Georgia is expected to face its first test – whether it has fulfilled the 12-point conditions for being granted EU membership candidate status. While it is highly plausible that Georgia will not be able to fully implement all twelve recommendations (36), it is also clear that the decision will be influenced to a certain extent by political factors too. Whatever the decision made in Brussels, it will influence domestic politics in Georgia, strengthening or weakening the legitimacy and electoral position of the ruling party and/or the key opposition parties.

Data: UN COMTRADE, 2023

Given Georgia’s unwavering public support for EU membership, it is critical for Georgia to be anchored in the European space via practical measures beyond obtaining candidacy status. Therefore, it is necessary for the EU and Georgia to establish new milestones for Georgia’s integration into the EU. This could be achieved by strengthening sectoral integration to bring concrete benefits in the short and medium-term future, working towards Georgia’s integration in the EU’s single market, and enhancing cooperation in the security sector. Whether the electoral outcome of 2024 and generational changes in leadership will deliver a government demonstrating more initiative, determination and capacity to move forward remains to be seen.

There are several ideas, such as accession to the EU single market and political space based on the European Economic Area (EEA) model and staged accession, that could be relevant for the case of Georgia. However, an in-depth analysis is required to determine how these models could be adapted to suit Georgia’s specific situation. It is also important to pay attention to changing the prevailing perception within the EU of Georgia as just marginally and formally belonging to Europe: this will require investment in strategic communication efforts. The European Political Community (EPC) initiative possesses fruitful potential for Georgia which should use this opportunity to strengthen ties, so that Georgia’s visibility on the EU’s radar screen is enhanced.

The EU is expected to maintain its conditionality principle in Georgia and strengthen efforts to prevent Russian sanctions evasion via third parties without creating a sense of unfairness in the country. Political mediation in Georgia needs a new impetus backed by political and institutional support by the EU. One idea could be to enable local politicians (and their counterparts from other associated countries with an EU membership perspective) to actively participate in the work of the European Parliament, although without being granted voting rights (37).

The European political parties, whose role in the EU’s political space has significantly increased over time, contribute to the EU integration process via engaging with their sister parties beyond the EU, including in Georgia, although the local parties have obviously underexploited the huge potential of such collaboration. Their role in facilitating dialogue among the political parties, and on the other hand assisting local sister parties in improving internal party democracy mechanisms, needs to be strengthened.

From the regional perspective, one important decision to be made is whether to consider the three applicants – Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia – separately, to treat two (Moldova and Ukraine) as more advanced and the other (Georgia) as a separate case, or to try to revive the Association Trio platform. The latter option implies mediating reconciliation between the Ukrainian and Georgian leaderships (admittedly less likely under the current GD government), but may yield benefits in endowing the Trio with stronger negotiation power in a framework of mutual support, while also making the task easier for Brussels.

Another step to streamline Georgia’s EU integration process would be via improved cooperation and coordination with the six Western Balkan countries. The EU is expected to use the same methodology to assess the progress of Georgia, Ukraine and Moldova. The Western Balkan countries have been on the EU accession path for years and have valuable experience that they can share with the Trio countries, who face similar challenges related to corruption, rule of law, and democratic governance.

Moreover, encouraging dialogue between the Western Balkan countries and ‘EU Associated Trio’ at the governmental, non-governmental, and think tank levels will shift the competition logic to a cooperation logic. The EU’s recent decisions to grant candidate status to Ukraine and Moldova and promise membership to Georgia in a historically short timeframe have made the Western Balkan countries increasingly sensitive to the possibility of their accession process being overshadowed by the Ukraine question. Thus, promoting constructive engagement and partnership between these countries could pave the way for a more effective and inclusive European integration process, and benefit both sides.

Improving strategic communication with Georgian citizens is of paramount importance as there are still many misconceptions and misunderstandings about the EU among the Georgian public, mainly focusing attention on the benefits (primarily social and economic) and less on the responsibilities undertaken by the country along the integration path. One suggestion would be to involve Georgian community leaders in projects like ‘How does the EU work?’. This project, implemented with limited resources by the Brussels-based not-for-profit organisation European Alliance for Georgia, has demonstrated the importance of having a clear understanding of EU policies, EU decision-making and the enlargement process. On the other hand, there is a need to help civil servants acquire better hands-on knowledge of EU processes, procedures and standards that may be achieved through specialised exchange programmes (e.g. the EU’s Seconded National Experts Programme) and institutionalised participatory cooperation between organisations with similar remits.

Autumn 2023 is shaping up to be a decisive season for Georgia. For the first time, the European Commission is set to assess Georgia through its enlargement package, alongside the Western Balkan countries, Ukraine, and Moldova. This impending progress report hinges on Georgia’s ability to fulfil the twelve recommendations and will be instrumental in deciding whether to bestow candidate status upon the country.

For Georgia and its leadership the clock is ticking. The urgency of reducing political polarisation, forging agreements beyond parochial political interests and propelling forward the necessary reforms to advance on the twelve steps cannot be overstated.

In the context of a changing world order and shifting geopolitical dynamics, Georgia’s unique geographical location is also a key asset. Therefore, Georgia should be seen – and indeed see itself – not just as a small and weak country egocentrically seeking to enhance its own security and reap other prospective benefits, but as a sovereign state with a number of comparative advantages and the potential not just to ask and take but also to work and give.

Russia’s war against Ukraine has been a key driver in redefining the EU’s enlargement paradigm and its vision of the neighbourhood. There is a real momentum towards expanding the EU’s borders. This presents a historic opportunity for Georgia – a unique chance that, if missed, may never recur.

References

1. NDI, ‘Taking Georgian’s pulse’, 3 May 2023 (https://www.ndi.org/sites/ default/files/NDI%20Georgia_March%202023%20telephone%20poll_ Eng_PUBLIC%20VERSION_FINAL_03.05%20%281%29.pdf).

2. ‘How does oligarch Bidzina Ivanishvili de facto rule Georgia?’, Jam News, 27 June 2022 (https://jam-news.net/how-does-oligarch-bidzina- ivanishvili-de-facto-rule-georgia/).

3. ‘What is wrong with the Georgian opposition?’, Jam News, 21 November 2022 (https://jam-news.net/what-is-wrong-with-the-georgian- opposition/).

4. European External Action Service, ‘A way ahead for Georgia’, 18 April 2022 (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/210418_ mediation_way_ahead_for_publication_0.pdf).

5. NDI, ‘Taking Georgian’s pulse’, op.cit.

6. ‘Saakashvili fears for his life in Georgian detention’, Politico, 23 December 2022 (https://www.politico.eu/article/mikheil-saakashvili- imprisoned-former-georgia-president-fears-for-his-life-daily/).

7. Freedom House, ‘Georgia’, 2022 (https://freedomhouse.org/country/ georgia/freedom-world/2022).

8. According to a poll by the National Democratic Institute (NDI), one in two Georgians does not trust any of the Georgian TV channels (which is a significant increase from 20 % in 2019). See ‘Taking Georgian’s pulse’, op.cit.

9. UNDP, ‘Media monitoring for 2021 local elections in Georgia’, 14 December 2012 (https://www.undp.org/georgia/publications/media- monitoring-2 021-local-elections-georgia).

10. Kvashadze, A., ‘Foreign fighters in the Russia-Ukraine war’, 2022 (https://gfsis.org.ge/publications/view/3269).

11. ‘Economy ministry: Georgia ranks 1st among 191 countries in Ukraine aid supply’, Agenda.Ge, 11 April 2022 (https://agenda.ge/en/ news/2022/1208).

12. UNHCR, ‘Ukraine refugee Situation’, 2023 (https://data.unhcr.org/en/ situations/ukraine).

13. ‘25 generators sent by Georgian govt arrive in Ukraine’, Civil.ge, 6 January 2023 (https://civil.ge/archives/520871).

14. ‘Grigory Karasin on relations between Georgia and Russia’, 24 March 2022 (https://agenda.ge/en/news/2022/907).

15. ‘The head of the European Commission on Georgia: the EU is preparing sanctions against those who help Russia’, Frontnews Ge, ‘18 January 2023 (http://www.frontnews.ge/en/news/details/50703).

16. ‘Protesters In Tbilisi decry Georgian government’s inadequate support for Ukraine’, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 1 March 2022 (https:// www.rferl.org/a/ukraine-invasion-tbilisi-protest-georgia/31731006. html).

17. ‘TI Georgia: Georgia’s economic dependence on Russia increased in 2022’, Civil.ge, 22 February 2023 (https://civil.ge/archives/526770).

18. Ministry of Internal Affairs of Georgia, ‘Statistics on border crossings to Georgia’, November 2022 (https://info.police.ge/uploads/63a5b1403ac06. pdf).

19. ‘Russians register an average of 1 300 companies per month in Georgia – Transparency International’, JAM News, 25 July 2023 2021 (https://jam- news.net/russians-register-companies-in-georgia/).

20. ‘Russia abolishes visa regime and lifts ban on airline flights with Georgia starting May 15’, Civil.ge, 10 May 2023 (https://civil.ge/archives/541553).

21. National Statistics Office of Georgia (Geostat), ‘GDP Growth Data’ 2023 (https://www.geostat.ge/en).

22. ‘EU “taking appropriate steps” on Georgia’s alleged spying on EU diplomats’, Civil.ge, 17 September 2021 (https://civil.ge/archives/441030).

23. ‘GD leaders criticize EU Ambassador’, Civil.ge, 24 September 2021 (https://civil.ge/archives/442367).

24. ‘MEPs cancel Tbilisi visit as Georgian Speaker “didn’t find time to engage”’, Civil.ge, 22 January 2022 (https://civil.ge/archives/468003).

25. ‘German Foreign Minister: We see attempts to deviate the country from the pro-European course’, Georgia Today, 23 March 2023 (https:// georgiatoday.ge/foreign-minister-of-german-we-see-attempts-to- deviate-the-country-from-the-pro-european-course/).

26. Council of the European Union, ‘Association Implementation Report on Georgia’, 12 August 2022 (https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-117842022-INIT/en/pdf?fbclid=IwAR0Rvoq7lQj8YL3-PMfjjOdai5oz2unGKvAOT89IH9gsbL2qq-lslAq-HRo).

27. See, e.g. ‘Kaladze on the position of Annalena Baerbock: This person is out of touch with reality’, Georgia Today, 23 March 2023 (https://georgiatoday.ge/kaladze-on-the-position-of-annalena-baerbock-this- person-is-out-of-touch-with-reality/).

28. European External Action Service, ‘Georgia: Statement by the High Representative on the adoption of the “foreign influence” law’, 7 March 2023 (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/georgia-statement-high- representative-adoption-%E2%80%9Cforeign-influence%E2%80%9D- law_en).

29. ‘Georgian Dream presents election program’, Civil.ge, 2 October 2020 (https://civil.ge/archives/373252).

30. ‘Georgia formally applies for EU membership’, DW, 3 March 2022 (https://www.dw.com/en/georgia-formally-applies-for-eu- membership/a-61001839).

31. ‘Ukraine’s Zelenskiy summons Georgian ambassador over ailing ex- president’, Reuters, 4 July 2023 (https://www.re uters.com/world/europe/ ukraines-zelenskiy-summons-georgian-ambassador-over-ailing-ex- president-2023-07-03/).

32. ‘Interview with Irakli Kobakhidze, chairman of Georgian Dream’, 1 TV.GE, 5 July 2022 (https://1tv.ge/video/qartuli-ocnebis-tavmjdomare- irakli-kobakhize-tavisufalikhedva-live/).

33. ‘Tens of thousands rally in Tbilisi to defend European future’, Civil.ge, 21 June 2022 (https://civil.ge/ka/archives/497223).

34. European Commission, ‘Opinion on the EU membership application by Georgia’, 17 June 2022 (https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/ detail/en/QANDA_22_3800).

35. ‘Association Implementation Report on Georgia’, op.cit.

36. According to the Commission’s oral assessment, to date, Georgia has fulfilled only 3 steps out of 12. See European Commission, ‘Press remarks by Neighbourhood and Enlargement Commissioner Oliver Várhelyi, following the informal General Affairs Council’, 22 June 2023 (https:// ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_23_3460).

37. Lavrelashvili, T., ‘It is possible for MEPs to successfully engage in non-EU countries’ domestic affairs – here’s how’, Parliament Magazine, 4 May 2023 (https:/www.theparliamentmagazine.eu/news/article/t-is-possible-for-meps-to-successfully-engage-in-noneu-countries-domestic-affairs-heres-how).