Hardly any war has ever been fought exclusively with regular soldiers. Notwithstanding this truism, the increasing prominence of state-sponsored armed and mercenary groups has notably expanded the repertoire of contemporary warfare: over the past decade such groups have been deployed both in support of regular armed forces and as shadow armies in conflict theatres from Ukraine to Mozambique. Apart from their flexibility and relative cost efficiency, the prime benefits of these groups derive from the fact that they provide plausible deniability for state actions, exercise an unconstrained licence to kill, and escape the restrictions of the jus ad bellum and jus in bello principles under international law. Even in the case of serious violations of humanitarian and human rights law, they can rarely be held accountable.

Violent conflicts always provide ample opportunities for enrichment, exploitation and the exercise of covert influence. In these contexts, mercenary and irregular armed groups are frequently deployed either on behalf of states or with their tacit permission. Thus, while states outsource the organisation and conduct of violence, they remain the main contractors of such groups (1), rendering the designation of ‘private military company’ (PMC) something of a misnomer. Moreover, while PMCs often pursue commercial interests, their missions, resources and protection from prosecution usually derive from

Commercial companies seldom have the personnel and equipment to provide security beyond property protection. To an important extent, the key component of the PMC business model is the capability to undertake offensive combat operations. PMCs with combat units commit assault and homicide and often use weapons of war. None of this can be directly attributed to the contractor. PMCs recruit former intelligence officers, special forces, former police officers, pilots or security guards; some are highly specialised, while others offer a broad portfolio of skills. While PMCs’ activities encompass a wide range of sectors, the most significant field of activity is undoubtedly the provision of combatants or security forces as well as armaments.

This Brief explores the sphere in which Russia’s state-controlled irregular armed groups (2) operate and the scope of their activities, focusing in particular on the notorious Wagner Group and their impact on violent conflicts.

Russia's irregular armed groups

While there are numerous publications on Western private military and security companies (3), until recently Russia’s irregular armed groups have garnered comparatively little scholarly attention (4). This is at odds with the fact that the importance of state-controlled irregular armed groups has been increasing for the Kremlin since it began its war against Ukraine in 2014/15 and its military intervention in Syria in 2015, followed by its increasingly assertive involvement in armed conflicts in African and Asian countries. Currently, Russian-sponsored irregular armed groups operate in Africa, the Middle East, Asia and Latin America, and include military-equipped units in Ukraine, the Central African Republic, Libya, Mali, Sudan, Syria, and Venezuela.

A defining feature of such paramilitary groups is that they operate with the threat of using or actual use of physical force. While some of these groups operate below the threshold of overt combat operations, they share the common characteristic of having military force at their disposal. Russian-sponsored irregular armed groups operate primarily by using a combination of hard and sharp power tactics unless their activities are limited to security services.

Combatants in state-sponsored irregular armed groups, particularly PMCs, are often referred to as mercenaries. Article 47 of the 1977 First Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions stipulates six criteria for mercenaries: A mercenary is any person who: ‘(a) is specially recruited locally or abroad in order to fight in an armed conflict; (b) does, in fact, take a direct part in the hostilities; (c) is motivated to take part in the hostilities essentially by the desire for private gain and, in fact, is promised, by or on behalf of a Party to the conflict, material compensation substantially in excess of that promised or paid to combatants of similar ranks and functions in the armed forces of that Party; (d) is neither a national of a Party to the conflict nor a resident of territory controlled by a Party to the conflict; (e) is not a member of the armed forces of a Party to the conflict; and (f) has not been sent by a State which is not a Party to the conflict on official duty as a member of its armed forces’ (5).

This definition criminalises mercenaries. However, it is also hardly applicable in practice, because at least one criterion is usually missing. International humanitarian law distinguishes between combatants,i.e. persons authorised to participate directly in hostilities, and non-combatants in international armed conflicts (6). Combatants are considered to be members of armed forces and must be identifiable as such; they are authorised to engage in acts of violence, but only to the extent that they have been authorised to do so by a party to the conflict (7). Combatants cannot be punished per se for their participation in acts of violence, while non-combatants face criminal prosecution. Legally, employees of commercial security and military companies become combatants under the Geneva Conventions only if they are under the command of regular armed forces.

Russian-sponsored irregular armed groups consist of de facto combatants, even though their de jure status may be disputed. Against the backdrop of the war against Ukraine, recent legal amendments adopted the term ‘volunteer’ to designate irregular combatants, equating combatants from the Wagner Group with ‘volunteers’ that formed the pro-Russian separatist battalions in 2014/15 in Ukraine. ‘Volunteers’ are thus portrayed as part of an overall military-patriotic effort, but their legal status remains vague (8). On 20 April 2023, Russia’s State Duma finally granted Wagner combatants the status of veterans of armed conflicts (9).

A defining feature of such groups is that they operate with the threat of using or actual use of physical force.

Under international law, combatants are treated as a party to a conflict. However, combatant status applies only to an interstate armed conflict – meaning that the legal status cannot be assigned in the context of civil or interstate wars. Employees of PMCs can be granted combatant status even if they are not members of regular armed forces: they would then also be legitimate military targets, they could be treated as prisoners of war, and they could also be prosecuted. However, it is often impossible to determine whether private security or military companies are integrated into the command structures of regular armed forces. It is precisely the ambiguity of their status and the at times fuzzy distinction between legal ‘private security companies and illegal ‘private military companies’ that allows state actors to deploy them arbitrarily.

As legal entities, PMCs cannot be prosecuted in either national or international courts for violations of the law. At best, the employees of PMCs can be prosecuted on the basis of individual criminal responsibility for war crimes, crimes against humanity, or genocide – crimes that are notoriously difficult to prosecute. The effort to hold PMCs to account is further complicated by the fact that these groups usually enter into immunity agreements with the contracting states (10). One attempt to subject private security and military companies to a code of conduct is the Montreux Document, adopted in September 2008 and signed by 58 states by 2021, but not by Russia, Israel and Turkey (11). However, as is the case with the majority of such documents, it is not binding under international law.

PMCs usually enter into immunity agreements with the contracting states.

As ‘armed formations’ are illegal under the Constitution and the Criminal Code (12) in Russia, PMCs have been seeking legal regulation of their status since 2017 (13). Russian commercial security companies have an interest in distinguishing themselves from mercenaries or terrorists.

Russia's corporate warriors

Although the Wagner Group receives the most media attention, there are almost a dozen other Russian private security or military companies on the market. The RSB Group, MAR, Shchit (Щит = ‘shield’), Moran Security Group, Patriot, Redut-Antiterror (Center R) and Antiterror-Orel are among the most well-known of these. The following overview does not claim to be exhaustive, but serves to illustrate the scope of services offered.

The RSB Group (Russkaya Slushba Bezopasnosti, the Russian Security Service) offers protection from ‘military-terrorist operations’ (14). It advertises its services as respecting relevant UN Security Council resolutions and the UN Charter and adhering to the international ‘Code of Conduct for Private Security Companies’. RSB specialises in protection against Somali pirates, hostage rescue and espionage.

Several Russian military companies are active in Syria. One of them is Shchit, which was established in 2018 and is based in Kubinka near Moscow – very close to a unit of the Special Airborne Forces (Spetsnaz). Its task in Syria was to guard facilities and infrastructure belonging to Stroytransgaz, a company owned by an acquaintance of Vladimir Putin, the oligarch Gennady Timchenko. Stroytransgaz has interests in the Al Sharqiya phosphate mines near Palmyra, two gas processing plants, and a gas pipeline. Shchit was also apparently involved in combat operations, with the deaths of three Shchit employees reported in July 2019 (15). Apparently, Shchit transmogrified into the PMC Redut after 2019.

According to Igor Girkin, an ex-officer of the GRU military intelligence agency who rose to prominence during the 2014 annexation of Crimea and the Russian-fuelled war in the Donbas,the Redut company is also operating in Syria to protect Gennady Timchenko’s subsidiaries (16). The Patriot company operates in Syria as well, allegedly under the direct control of Russian Defence Minister Shoygu. The military company Antiterror-Orel is one of the oldest such companies in Russia. It was founded by reservists and veterans of the GRU and the Navy, as well as by members of the FSB’s Vympel Department (17). Since 1998 it has been engaged in protection of industrial sites and provides military training (18). The Moran Security Group, originally an offshoot of Orel, advertises on its website that it has been providing security services since 1999 (19). These examples demonstrate the diverse range of services offered by Russian PMCs, the blurred lines between military and mere security services, the formal registration of these companies both in Russia and abroad, the frequent provision of security in exchange for the right to exploit natural resources and the pattern of recruitment among former special forces and military veterans.

The Wagner Group

The rise of the Wagner Group exemplifies the collaboration between Russia’s autocratic regime and organised crime elements, as well as demonstrating Moscow’s willingness to sacrifice large numbers of its own combatants on the battlefield. The Wagner Group is the most prominent of Russian state-controlled irregular armed groups, spearheading Russia’s aggressive all-out war against Western ‘spheres of influence’ and its goal of the resurrection of a Russian empire.

The Wagner Group was founded in the spring of 2014 by former Lieutenant-Colonel Dmitry Utkin. Utkin had already worked for the Moran Security Group and had previously been a member of the 2nd Special Reconnaissance Brigade of the Russian military intelligence service GRU and served as a commander of the Slavonic Corps PMC in Syria (20). As it evolved, the Wagner Group recruited into its ranks former members of the Slavonic Corps, the GRU, the Russian Airborne Forces (VDV), various Spetsnaz units, and former Ministry of Defence staff. This force was initially assembled to provide military support to the separatists in Ukraine’s Donbas region and later on for ensuring strict vertical subordination of separatist field commanders under the military command of Moscow, extending to the punishment and killing of commanders deemed defiant or disobedient.

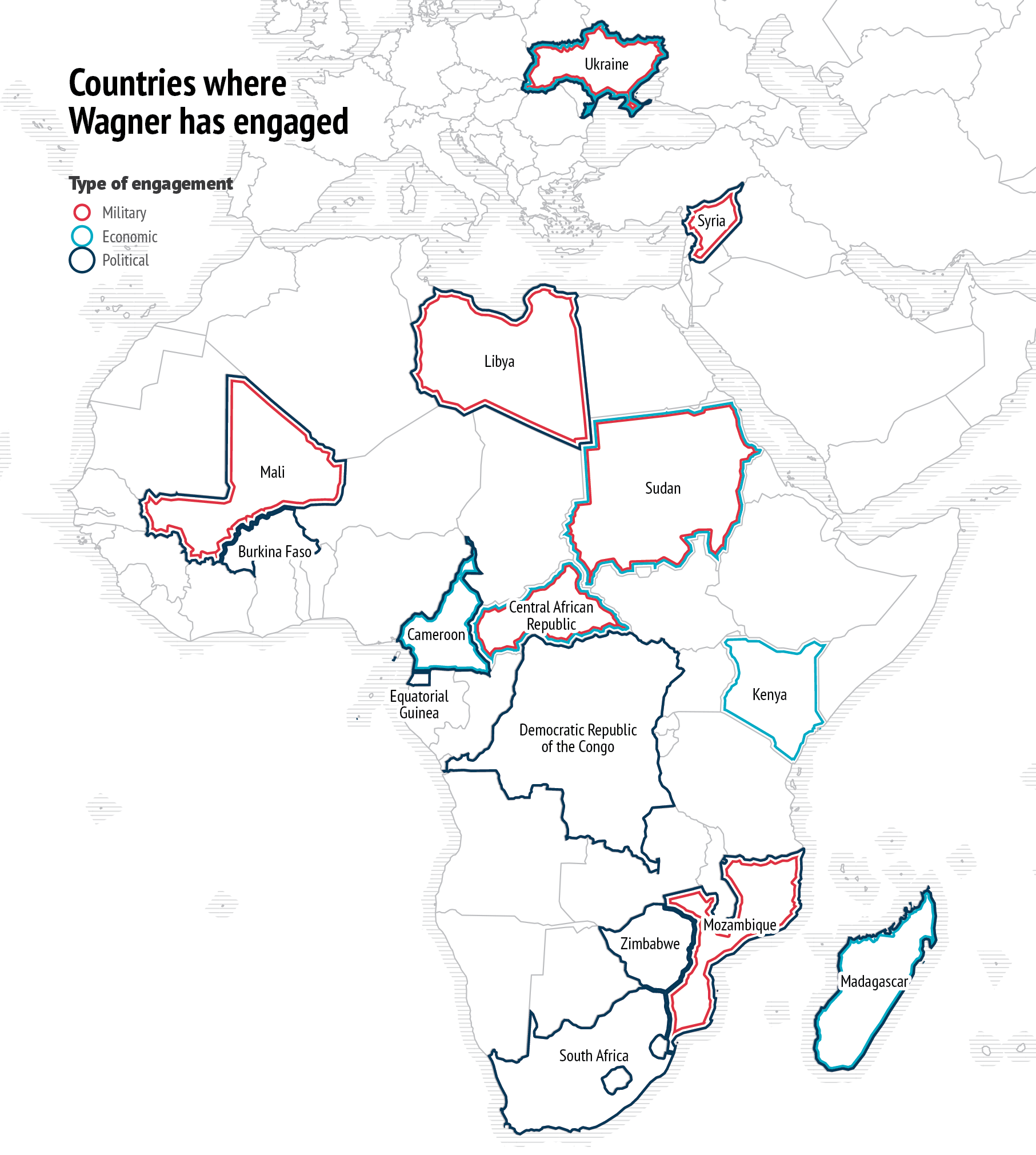

Data: Global Initiative, 2023; European Commission, GISCO, 2023

The Wagner Group has been active in Ukraine, Syria, Sudan, South Sudan, Libya, the Central African Republic, Madagascar and Mozambique, Botswana, Burundi, Chad, DR Congo, Congo-Brazzaville, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, and the Comoros Islands. Wagner operates under the aegis of the GRU, which equips, trains and commands it – despite Wagner’s regular rows with the Ministry of Defence (MoD) over the provision of heavy weapons, ammunition and logistical support. Frictions with the MoD exist over tactics too, but Wagner offers two crucial benefits for the Kremlin – its casualties are domestically invisible and it compensates for the deficits of the regular army. In early 2016, the Wagner Group numbered about 1 000 operatives. In August 2017, this number had reportedly grown to 5 000, and in December 2017 it had risen to about 6 000 (21). In January 2023, a Ukrainian news agency, referring to British sources, estimated the number of Wagner combatants in Ukraine at 50 000 men (22). The exact numbers are difficult to asses, however, as mercenaries sign temporary contracts and rotate after deployments.

Furthermore, a substantial number of Wagner combatants have been killed or severely wounded during the war against Ukraine. Fighters enlisted in the Wagner Group include convicts, mostly murderers and violent offenders, who since the summer of 2022 have been recruited directly from penal colonies for deployment to the frontline in Ukraine, in exchange for promised pardons and amnesties. Estimates of the number of recruited convicts range from 20 000 to 50 000 (23). These convicts, with few exceptions, are used as cannon fodder. In this author’s estimate, Wagner has currently approximately 5 000 professional combatants on active service in Ukraine and probably an additional number of 20 000 convicts (roughly 80% of all Wagner combatants).

Wagner in Ukraine

In early May 2014, the Wagner Group helped separatist forces overcome Ukrainian security forces, take control of local municipal administrations and towns, seize ammunition depots and conduct reconnaissance. Wagner mercenaries also meted out retribution in the ‘Lugansk People’s Republic’ against wayward pro-Russian battalions (24). In Ukraine, the Wagner Group practises what it has learnt in Syria and Africa: ruthless, indiscriminate murder. The Wagner Group was involved in the shooting down of a Ukrainian military aircraft in June 2014, the storming of both Luhansk airport and Debaltseve, as well as, in 2022, the massacre committed in the town of Bucha. From August 2022 onwards, the siege and partial capture of the cities of Soledar and Bakhmut in Donbas was conducted by Wagner troops. The Wagner Group suffered severe losses. Ukrainian estimates claim the loss of up to 40 000 Wagner combatants (25), figures that cannot be independently confirmed, but seem to be overstated given the overall number of combatants.

Wagner in Syria

After Wagner ‘proved its worth’ in Donbas, the Group joined Russia’s military intervention in Syria in September 2015 (26). In Syria Prigozhin, who controls the oil company Evro Polis, was involved in recapturing occupied oil and gas fields on behalf of the Syrian Energy Ministry. 25 % of the profits from the oil and gas fields went to Evro Polis after their liberation from Islamic State (IS) control. The Wagner Group fought with over 1 000 fighters in Syria where it still operates. Equipped and armed by the Russian Ministry of Defence and supported from the air by Russian fighter aircraft, the Wagner mercenaries carried out the ‘dirty work’ against IS on the ground. The Wagner Group deploys its forces in the field as shock and awe troops. Wagner also trains and recruits local combatants, and commands anti-insurgency operations. In countries such as Syria, Libya, Mali or the Central African Republic, the Wagner Group maintains autocratic regimes in power or assists putschists to gain power.

Wagner in Libya

In 2020, Wagner fighters, financed in part by the United Arab Emirates (UAE), supported General Khalif Haftar’s forces in Libya. According to information provided by the chairman of the Libyan ‘High Council of State’, Khalid al-Mishri, in December 2021, at times as many as 7 000 Wagner fighters have been deployed in Libya, with 30 combat aircraft at their disposal (27). However, these figures should be treated with caution. A UN investigative report covering the period from March 2021 to April 2022 proved that the Wagner Group violated international law in supporting Khalif Haftar. By the spring of 2022, approximately 900 of the previously 2 200 Wagner combatants were believed to remain in Libya—the rest having been withdrawn to fight in Ukraine (28).

Wagner in Sub-Saharan Africa

PMCs are part of a broader strategy to reclaim Russian influence in Africa (29). Wagner mercenaries had been deployed to Sudan, the Central African Republic (CAR), Madagascar, Libya, Mali and Mozambique as of 2017. By the end of 2019, the Wagner Group already had an office in 20 African countries. In September 2019, Wagner sent between 160 and 200 of its personnel to Mozambique to subdue the insurgency of the so-called Central African Province of the Islamic State (IS-CAP) on behalf of the incumbent government. However, the inability of the Wagner force to combat the IS-CAP insurgency led to a humiliating withdrawal in December 2019.

PMCs are part of a broader strategy to reclaim Russian influence in Africa.

After a 2017 meeting between President Putin and Omar al-Bashir, then president of Sudan, in Sochi, security cooperation between Russia and Sudan picked up steam. In late July, 500 Wagner fighters appeared on the border between Sudan and the CAR. The 2021 military coup in Sudan that had replaced the interim civilian government was supported by the Russian government, with Wagner mercenaries quashing anti-government protests (30). According to Samuel Ramani, author of a book on Wagner in Africa, the Wagner Group subsequently switched sides and supported the insurgent General al-Burhan. Since April 2023, Wagner allegedly sides with the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) that fight against the troops of General al-Burhan, who is now the country’s de facto leader (31). Meanwhile, Prigozhin denies that Wagner troops have been present in Sudan for the past two years (32). In Sudan, one of Prigozhin’s companies was allowed to export gold from a Sudanese mine. In April 2023, the Kremlin said that 170 ‘civilian advisors’ had arrived in the CAR to train government forces. Back in 2017, the UN Security Council had suspended an arms embargo on the CAR and approved the deployment of 175 Russian trainers for the local military. With the exception of five soldiers, all were Wagner mercenaries. In the CAR, the Wagner Group provided security protection services for President Faustin-Archange Touadéra. Since December 2020, an additional 300 soldiers from the Russian army have reportedly supported the president against opposition rebels. Russian Special Forces, Wagner mercenaries and the CAR’s pro-government military protected President Touadéra during his presidential election campaign in December 2020 and undertook joint military operations in the Bangui area against insurgent groups. A UN working group on human rights violations by mercenaries accused the Russian mercenaries in the CAR of committing serious human rights abuses along with the pro-government army, including rape, summary executions and targeted killings, torture, enforced disappearances, and murders (33).

The presence of the Wagner Group makes it considerably more difficult for the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Republic (MINUSCA) to operate in the CAR, because they restrict the mission’s freedom of movement. Since the capture of Boda, the Russian-controlled timber company Bois Rouge has been exporting precious wood from the CAR to Russia on a large scale. The importer in Russia, Broker Expert, is based in St. Petersburg and is a trading partner of Prigozhin’s empire. Since at least 2019 companies from Russia have been granted long-term mining licenses by the CAR government, particularly for gold and diamond mines in Bambouri, Bornou and Adji (34).

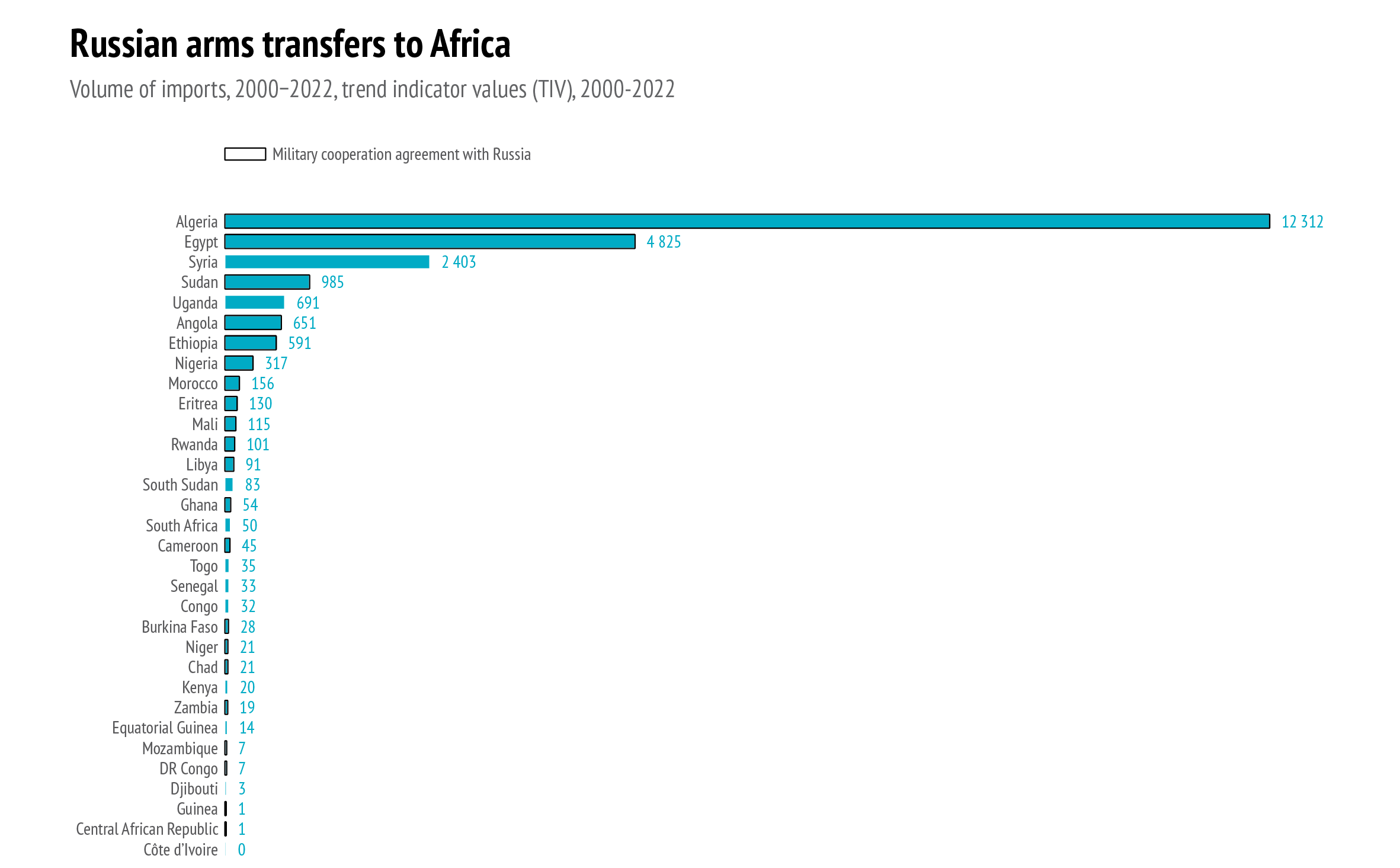

NB: TIV is a system developed by SIPRI to measure the volume of international transfers of major conventional weapons using a common unit. TIV is intended to represent the transfer of military resources rather than the financial value of the transfer.

Data: SIPRI, Arms Transfers Database, 2023

Wagner in Mali

Russia’s intervention in Mali marks the beginning of its military power projection in West Africa. Russia was quick to step in and fill the security vacuum left by President Macron’s political defeat in Mali and the subsequent withdrawal of French troops from the country (35). The Wagner mission in the CAR can be interpreted as a ‘blueprint’ for its operations in Mali. While French units and UN missions have been unable to demonstrate success against Islamist groups for years, Wagner mercenaries claim to ‘resolve’ conflicts with insurgents within a matter of weeks. Approximately 1 000 Wagner Group fighters have been operating in Mali since the autumn of 2021. Wagner was only able to make inroads in the country due to the failure of the EU training mission in Mali. During the EU mission, the security situation in Mali deteriorated progressively.

Wagner’s combatants provide agile ground forces for reconnaissance, sabotage operations and indiscriminate killing.

Initially the Wagner Group enjoyed a comparatively good reputation among Malian soldiers—a group of military officers had seized power in Mali in August 2020—because Wagner provided material and food, and its personnel accompanied Malian troops on combat missions. Human rights abuses committed by Malian soldiers did not raise any concerns among their Russian auxiliaries. Over time, however, Malian troops have become increasingly disillusioned with the Wagner Group as it has come to dominate joint operations. Moreover, one consequence of the Wagner forces’ indiscriminate killing operations was that relatives of villagers who had been arbitrarily killed began to join jihadist groups, thus adding to their numbers. At the end of March 2022, a massacre in Moura, a Malian village with inhabitants from the Peul and Fulani ethnic groups, resulted in the deaths of between 200 and 400 people, and showed that the army and Wagner do not seek to distinguish between jihadists and civilians. On the ground, Wagner is dependent on logistics, enemy reconnaissance by the Malian military, and the Malian military’s knowledge of the local language and culture, which makes its forces quite vulnerable. The Wagner Group’s approach in Mali is similar to that which it has employed in Ukraine and Syria: it acts as a ruthless killing machine.

'Siloarchy': The fusion of oligarchic and military interests

Russia’s irregular military companies have become the regime’s agents of influence, war profiteers, and an auxiliary force for state security agencies. Russian irregular armed groups interact with the Russian Ministry of Defence, especially the GRU, as well as the FSB, the foreign intelligence service (SVR), and the presidential administration. Wagner’s combatants provide agile ground forces for reconnaissance, sabotage operations and indiscriminate killing. Part of Wagner’s modus operandi is ‘disciplining’ disobedient or recalcitrant elements among its own ranks through torture and killing.

Russia’s military companies are an instrument of Russia’s expansionist foreign policy. They can be deployed flexibly and covertly, as well as swiftly, and they cannot be held accountable for crimes, or only to a limited extent. Within their missions, business interests and military objectives are intertwined. Russia’s military companies serve to destabilise pro-Western and shore up anti-Western governments. Deaths and injuries among irregular combatants are officially invisible. The exploitation of lucrative gold, diamond, oil or gas deposits in the countries where these forces are active reflects the fusion of oligarchic and military interests.

The Wagner Group is a state terrorist group. In many ways, with its capacity for arbitrary violence, it represents the abolition of legal and civil standards of conflict behaviour. It embodies the coexistence of legal security apparatuses and commercial entrepreneurs of violence in Russia’s political regime. Providing Moscow with a cover of plausible deniability for Kremlin-backed operations in various parts of the world, Wagner’s troops penetrate regions of limited or fragile statehood and liquidate opponents there. Wagner is emblematic of the so-called ‘siloarchy’ in Russia, that is, the collusion between the power ministries (siloviki) and oligarchic interests.

Conclusion

European policymakers should be concerned about Wagner’s destabilising impact, because its presence in conflict-affected regions deepens societal divides, contributes to the recruitment of Islamist militants and undermines efforts to improve governance and security sector reforms. In order to curb the spread of Russian-sponsored irregular armed groups, the EU might consider offering training courses for policymakers in relevant countries, as well as for the security establishment and the media, on legal standards for private security and military companies. The EU could also consider enhancing ‘intelligence fusion’ capabilities among its Member States. Moreover it could trace the financial transactions of Russia’s ‘corporate warriors’ and take steps to block such transactions where possible. It could also sponsor fact-finding missions in order to document Wagner’s human rights violations. Indeed it could go further and on the basis of such findings declare the Wagner Group a terrorist organisation. Finally, the EU should consider offering leniency and exemption from prosecution to Wagner ex-combatants who are willing to cooperate in judicial investigations into war crimes.

References

1. Singer, P.W., ‘Corporate Warriors: The rise of the privatized military industry and its ramifications for international security’, International Security, Vol. 26, No 3, 2001/2002, pp. 186–220; Avant, D.D., The Market for Force: The consequences of privatizing security, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2005; Chesterman, S. and Lehnardt, C. (eds.), From Mercenaries to Market: The rise and regulation of private military companies, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2009; Eckert, A.E., Outsourcing War: The just war tradition in the age of military privatization, Ithaca, New York, 2016; Mandel, R., Armies without States: The privatization of security, Boulder,CO, 2002; Jones, S.G., et al, ‘Russia’s corporate soldiers: The global expansion of Russia’s private military companies’, Center for Strategic & International Studies, July 2021 (https://www.csis.org/analysis/ russias-corporate-soldiers-global-expansion-russias-private-military- companies).

2. The overarching term used here is ‘state-controlled irregular armed groups’. Private security companies and private military companies are treated as a subcategory. State-controlled irregular armed groups also include irregular (so-called volunteer) battalions. In contexts where such groups pursue commercial interests, the term ‘corporate warriors’ is used as a shorthand in this Brief.

3. ‘Corporate Warriors: The rise of the privatized military industry and its ramifications for international security’, op.cit., pp. 186–220.

4. Marten, K., ‘Russia’s use of semi-state security forces: The case of the Wagner Group’, Post-Soviet Affairs, Vol. 35, No 3, 2019, pp. 181–204.

5. International Committee of the Red Cross, ‘Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I), 8 June 1977’, International Humanitarian Law Databases (https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/ihl-treaties/api-1977/article-47/commentary/1987?activeTab=un defined).

6. International Committee of the Red Cross, ‘The principle of distinction between civilians and combatants’, International Humanitarian Law Databases (https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/en/customary-ihl/v1/rule1).

7. Liu, H.Y., ‘Leashing the corporate dogs of war: The legal implications of the modern private military company’, Journal of Conflict and Security Law, Vol. 15, No. 1, 2010, pp. 141–168; Médecins Sans Frontières, ‘Private Military Companies: Overview of the phenomenon’ (https://guide- humanitarian-law.org/content/article/3/private-military-companies/); Cameron, L., ‘Private Military Companies: Their status under International Humanitarian Law and its impact on their regulation’, International Review of the Red Cross, Vol. 88, No 863, 2006, pp. 573–611; From Mercenaries to Market: The rise and regulation of Private Military Companies, op.cit.

8. ‘Putin signs legislation banning “discrediting” and “fakes” about volunteers and mercenaries’, Meduza, 18 March 2023 (https://meduza. io/en/news/2023/03/18/putin-signs-order-banning-discrediting-and- fakes-about-volunteers-and-mercenaries).

9. ‘Gosduma dala naemnikam ChVK Vagner pravo na status “veteranov boevykh deystvii”’ [Russia’s State Duma grants Wagner mercenaries right to status of ‘combat veterans’], Ukrainska Pravda, 20 April 2023 (https://www.pravda.com.ua/rus/news/2023/04/20/7398772/).

10. A number of conventions on mercenaries are generally applicable to PMCs, including the International Convention against the Recruitment, Use, Financing, and Training of Mercenaries (ICRUFTM), Protocol (I) Addition to the Geneva Conventions, and the Organisation of African Unity’s Convention on the Elimination of Mercenarism in Africa (OAU CEM. See: Riordan, K., ‘International Convention against the recruitment, use, financing and training of mercenaries’, General Assembly resolution 44/34, New York, 4 December 1989 (https:// legal.un.org/avl/ha/icruftm/icruftm.html); ‘OAU Convention for the Elimination of Mercenarism in Africa, Libreville, 3rd July 1977’, International Humanitarian Law Databases (https://ihl-databases.icrc. org/en/ihl-treaties/oau-mercenarism-1977).

11. International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), ‘The Montreux Document on Private Military and Security Companies’, 11 June 2020 (https://www.icrc.org/en/publication/0996-montreux-document- private-military-and-security-companies).

12. The Constitution of the Russian Federation, Chapter 1, ‘The fundamentals of the constitutional system’ (http://www.constitution.ru/en/10003000- 02.htm).

13. Khodarenok, M., ‘Chastnye armii zhelayut uzakonitsja. Na kakikh osnovanijakh rabotayut rossijskie ChVK’ [Private armies wish to become legalised. The basis of the work of Russian PMCs], 26 July 2017 (www. gazeta.ru/army/2017/06/26/10736969.shtml).

14. See the front page of RSB’s website: https://rsb-group.org/about.

15. ‘Chastnaya armiya “Shchit” V Rossii razoblachena eshche odna ChVK, naemniki kotoriy gibnut v Sirii’ [Private army ‘shield’ another PMC exposed in Russia, whose mercenaries are dying in Syria], TSN, 29 July 2019 (https://tsn.ua/ru/svit/chastnaya-armiya-schit-v-rossii- razoblachena-esche-odna-chvk-naemniki-kotoroy-gibnut-v-sirii-1386135.html).

16. ‘“Patriot” i “Redut” Pomimo “Vagnera” v Sirii deystvuyut eshche 2 ChVK iz Rossii’ [‘Patriot’ and ‘Redoubt’ in addition to ‘Wagner’ in Syria, there are 2 more PMCs from Russia], TRT na russkom, 1 June 2021 (https:// www.trtrussian.com/novosti-rossiya/patriot-i-redut-pomimo-vagnera- v-sirii-dejstvuyut-eshe-2-chvk-iz-rossii-5624845).

17. ‘“V for Vympel”: FSB’s Secretive Department “V” behind assassination of Georgian asylum seeker in Germany’, Bellingcat, 17 February 2020 (https://www.bellingcat.com/news/uk-and-europe/2020/02/17/v- like-vympel-fsbs-secretive-department-v-behind-assassination-of- zelimkhan-khangoshvili/).

18. The site of Anti-terror Orel on the social network VKontakte does not specify the kind of sites or facilities they protect (https://vk.com/ topic-161255886_39956747).

19. See the MSG website: http://moran-group.org/en/about/index.

20. See Marten, K., ‘Russia’s use of semi-state security forces: The case of the Wagner Group’, Post-Soviet Affairs, Vol. 35, No 3, 2019, pp. 181–204; Hauer, N., ‘Russia’s favorite mercenaries’, The Atlantic, 27 August 2018 (https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/08/ russian-mercenaries-wagner-africa/568435/); Heinemann-Grüder, A., ‘Russlands irreguläre Armeen. Das Beispiel “Wagner”’ [Russia’s irregular armies: The case of Wagner], Osteuropa, Vol. 72, No 11, 2022, pp. 127-155.

21. ‘Glava apparata SBU Igor Gushkov: kto nam “slivaet” informatsiyu o boevikakh “Vagnera”? Ya ne mogu raskryvat nashi istochniki v FSB’ [The head of the SBU apparatus Igor Guskov: who is ‘leaking’ information about Wagner militants to us? I can’t reveal our sources in the FSB], Ukrajins’ki Novini, 8 October 2018 (https://ukranews.com/interview/2063- ygor-guskov-kto-nam-slyvaet-ynformacyyu-o-boevykakh-vagnera- ya-ne-mogu-raskryvat-nashy-ystochnyky-v).

22. Kobzar, Y., ‘Britanskaya razvedka nazvala kolichestvo “vagnerovtsev” na fronte v Ukraine’ [British intelligence identified a number of ‘Wagnerites’ at the front in Ukraine], UNIAN 20 January 2023 (https:// www.unian.net/war/britanskaya-razvedka-podschitala-chislo- boevikov-chvk-vagner-v-ukraine-12115905.html).

23. Liptak, K., ‘US believes Wagner mercenary group is expanding influence and took delivery of North Korean arms’, CNN, 22 December 2022 (https://edition.cnn.com/europe/live-news/russia-ukraine-war-news- 12-22-22/h_436bd7e67edbcf6307b6432165f9bffa).

24. ‘ChVK Vagnera razoruzhaet brigadu Odessa’ [PMC Wagner disarms the Odesa brigade], Agentstvo Voenkor.Info, 10 January 2015 (https://web. archive.org/web/20160915101646/http://voenkor.info/content/5570).

25. ‘Wagner Group loses about two-thirds of its personnel in battles for Bakhmut and Soledar’, Ukrinform, 18 January 2023 (https://www. ukrinform.net/rubric-ato/3655038-wagner-group-loses-about- twothirds-of-its-personnel-in-battles-for-bakhmut-and-soledar- expert.html).

26. On Wagner in Syria see Gabidullin, M., Wagner – Putins geheime Armee: Ein Insiderbericht [Wagner – Putin’s secret army – An insider report], Econ Verlag, Berlin, 2022; Al-Altrush, S. and Pitel, L., ‘Russia reduces number of Syrian and Wagner troops in Libya’, Financial Times, 28 April 2022 (https://www.ft.com/content/88ab3d20-8a10-4ae2-a4c5- 122acd6a8067); Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression (SCM), ‘Wagner in Syria: Complaint filed with European Court of Human Rights following the dismissal of the case in Russia’, 9 June 2022 (https://www.fidh.org/IMG/pdf/wagner-cedh-q_a-en.pdf); Gibbons- Neff, T., ‘How a 4-hour battle between Russian mercenaries and U.S. commandos unfolded in Syria’, New York Times, 24 May 2018 (https:// www.nytimes.com/2018/05/24/world/middleeast/american-commandos- russian-mercenaries-syria.html).

27. ‘Over 7 000 Russian mercenaries still in Libya: Al-Mishri’, Daily Sabah, 12December 2021 (https://www.dailysabah.com/world/africa/over-7000- russian-mercenaries-still-in-libya-al-mishri).

28. Erteima, M., ‘1,300 Wagner mercenaries sent from Libya to help Russian forces in Ukraine’, Anadolu Agency 26 March 2022 (https://www.aa.com. tr/en/russia-ukraine-war/1-300-wagner-mercenaries-sent-from- libya-to-help-russian-forces-in-ukraine/2545629); ‘More Russian mercenaries deploying to Ukraine to take on greater role in war’, New York Times, 25 March 2022.

29. Haidara, B., ‘La société militaire privée Wagner, l’instrument d’une guerre par procuration de la Russie contre la France dans son “pre- carré” africain?’, Autre Terre magazine, 2023 (forthcoming).

30. ‘Russia’s Wagner Group helps put down Sudan’s anti-government protests’, Warsaw Institute, 18 January 2019 (https://warsawinstitute. org/russias-wagner-group-helps-put-sudans-anti-government- protests/).

31. Ramani, S., Russia in Africa: Resurgent great power or bellicose pretender?, Hurst, London, 2023.

32. Khorton, D., Mvai, P. and Atanesyan, G., ‘Chem ChVK “Vagner” zanimaetsya v Sudane’ [What PMC ‘Wagner’ is doing in Sudan], BBC News, 24 April 2023 (https://www.bbc.com/russian/features-65371266).

33. Amin, M., ‘Syrian fighters participated in Wagner Group massacres in Central African Republic’, Middle East Eye, 9 June 2022 (https://www. middleeasteye.net/news/syria-fighters-wagner-group-attacks-central- african-republic).

34. Olivier, M., ‘Café, cash et alcool: au cœur du système Wagner, de Douala à Bangui’, Jeune Afrique, 12 August 2022 (https://www.jeuneafrique. com/1369001/politique/cafe-cash-et-alcool-au-coeur-du-systeme- wagner-de-douala-a-bangui/).

35. Haidara, B., ‘Analyse: Pourquoi Wagner prospère’, New African, 17 February 2022 (https://magazinedelafrique.com/politique/analyse- pourquoi-wagner-prospere/).