Summary

- Strengthening Europe’s defences requires more effective cooperation between national militaries. Building on bilateral and minilateral defence clusters offers the most realistic way to achieve this.

- Defence clusters can drive forward efforts to strengthen European military capabilities by advancing joint procurement, interoperability and operational coordination where EU-wide solutions prove difficult.

- The EU should focus on enabling and linking clusters by supporting individual initiatives and integrating them into a stronger and more coherent European defence ecosystem.

Europeans are adapting to a more threatening security landscape, marked by growing uncertainty about the durability and depth of US engagement in Europe. The blueprint is clear: more defence investment but also deeper cooperation between Member States on everything from the acquisition of military equipment to joint training and operations.

Organising effective cooperation among a large and diverse group of states, however, remains difficult. Fragmented national defence planning, diverging threat perceptions and competing industrial interests constrain collective action(1). The more ambitious the form of cooperation, the harder it is to agree on practical details. Ultimately these constraints mean that comprehensive, EU-wide solutions are often slow to emerge and limited in scope.

This Brief argues that small-group cooperation in the form of bilateral and minilateral defence clusters offers the most viable way forward. By bringing together countries with aligned threat perceptions, capabilities and political will, clusters allow for faster and deeper integration along both industrial and operational dimensions, while avoiding many of the obstacles that hinder Europe-wide approaches.

Defence clusters: Europe’s force multiplier

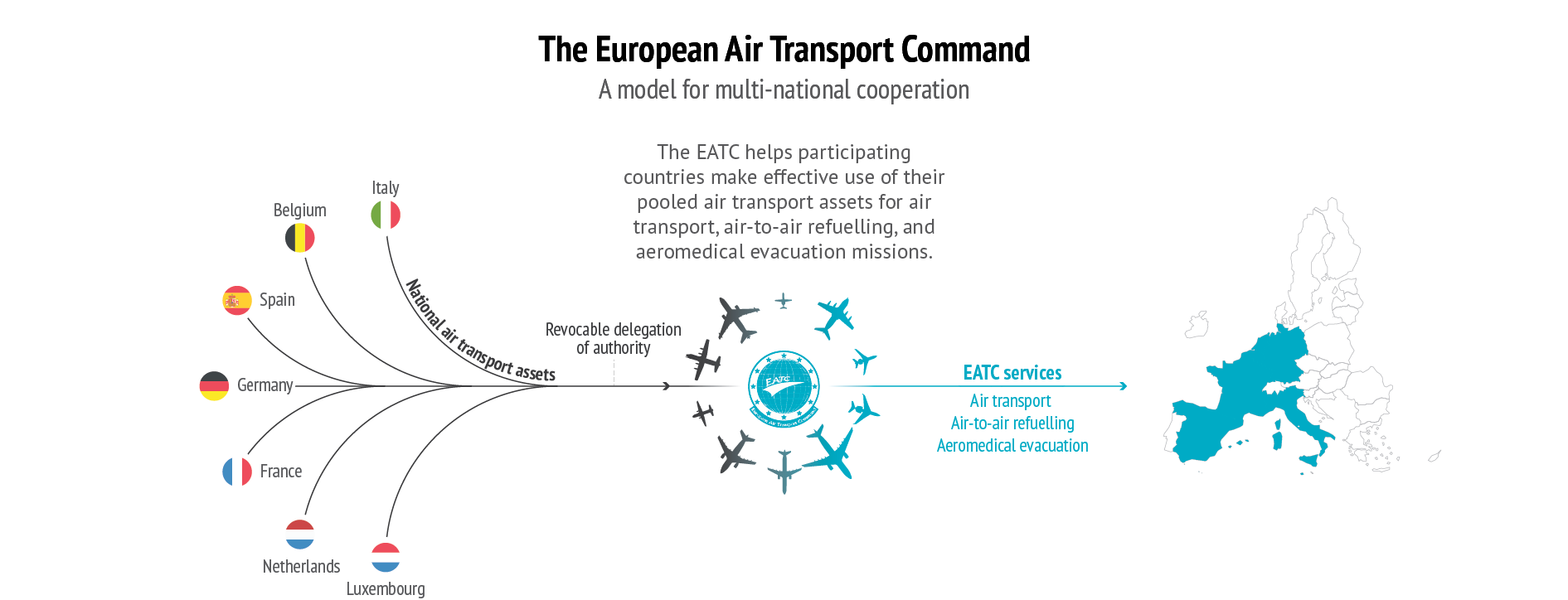

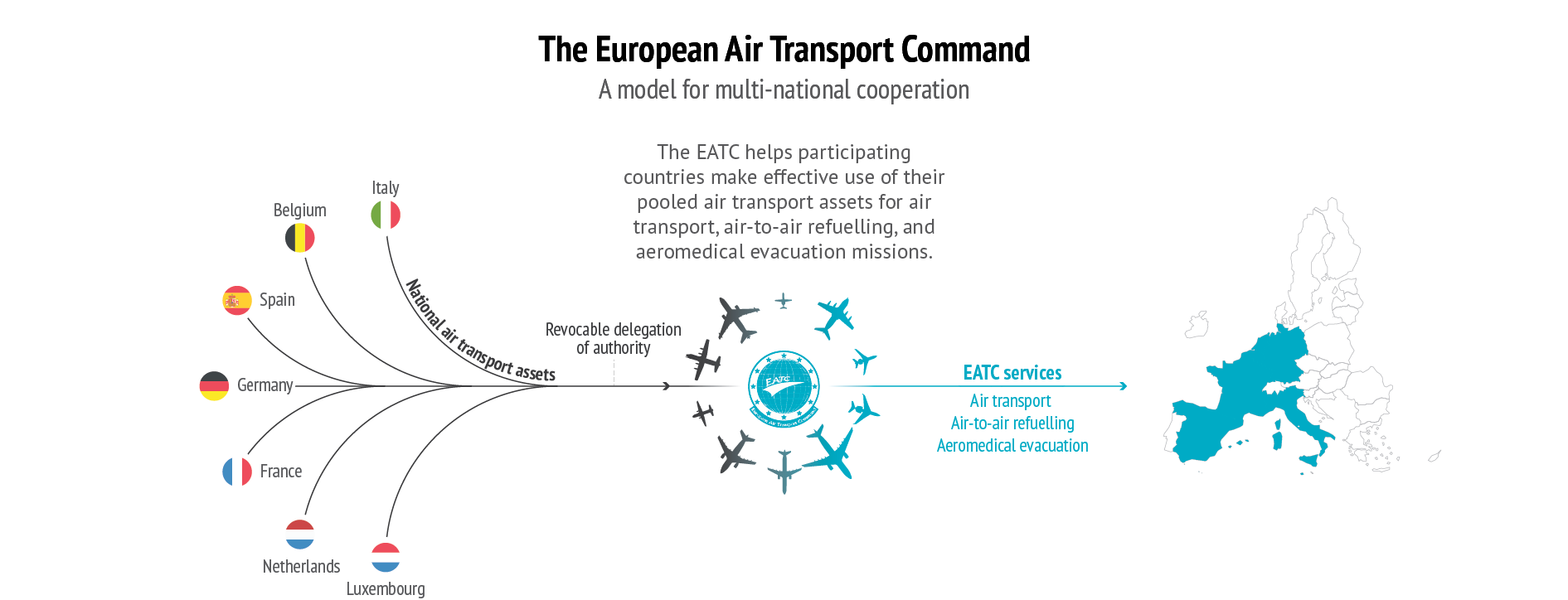

Cooperation between small groups is not new in European defence. Many of the most effective cooperation initiatives in Europe are minilateral. These range from capability development programmes like the Eurofighter to the pooling of air transport assets through the European Air Transport Command and the integration of national forces — as seen in the case of the Belgian and Dutch navies. Minilateral cooperation has gained momentum since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Europeans have come together in coalitions to provide Kyiv with specific capabilities, funding or training. The deepening of cooperation is most evident in Northern Europe, where a network of overlapping formats is effectively creating a regional ecosystem of defence cooperation between the Nordic and Baltic States, Germany, Poland and the UK(2).

Defence clusters allow smaller groups of states to overcome obstacles that often constrain broader European cooperation. First, clusters help countries overcome challenges in armaments cooperation such as diverging requirements, timelines and industrial interests. It is often simply easier to reach agreement on these issues in smaller groups as there are fewer actors and fewer competing priorities. Franco-Italian cooperation in the naval domain, which produced the FREMM frigate, is a case in point. The capability coalitions that have supported Ukraine with specific pieces of equipment show how minilateral formats can quickly coalesce around concrete needs(3). The CAVS armoured vehicle programme, a joint procurement initiative involving Finland, Latvia, Sweden, Germany, Denmark, Norway and the UK, is another example of this approach.

Second, clusters help in generating interoperability, enabling specialisation and even integration of national military forces. Belgian-Dutch naval cooperation is one of Europe’s most advanced examples of defence integration, encompassing coordinated procurement, joint training and maintenance and shared command. In the land domain, the Netherlands has integrated its mechanised forces into Germany’s. Meanwhile, Denmark, Finland, Sweden and Norway are working to integrate their air forces under a single command(4). The Franco-British Combined Joint Force aims to establish an all-domain joint unit; while the Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF) seeks to foster greater interoperability between the UK, the Netherlands, the Nordic countries and the Baltic States.

Third,smaller groups are often the only practical avenue for operational cooperation, helping overcome collective action problems in larger organisations. One recent example is the French-led task force Takuba, which deployed in the Sahel to fight jihadist insurgents from July 2020 until June 2022 and integrated contributions from a range of European special forces. Many NATO operations have effectively been small-group operations, including the recently launched Baltic Sentry and Arctic Sentry. Meanwhile, the Combined Joint Force and the Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF) are formations that can potentially be deployed. More recently, European countries have begun preparing for the possible deployment of a post-ceasefire reassurance force to Ukraine within the so-called ‘coalition of the willing’ which has also stood up a headquarters(5).

The success of defence clusters is above all linked to strategic fit. Cooperation succeeds when threat perceptions and requirements are tightly aligned. The intensity and urgency of the threat from Russia have driven the development of a dense network of overlapping initiatives across procurement, exercises and operational planning in much of Northern Europe. These include Nordic defence cooperation through NORDEFCO, joint participation of all Nordic and Baltic countries in the JEF, and capability projects in smaller constellations, such as CAVS or the CV90 armoured combat vehicle. The same group of countries has been particularly proactive in deepening cooperation with Ukraine through defence-industrial partnerships. Southern Europe offers many examples of defence cooperation, notably Franco-Italian naval and missile projects. However, these have not resulted in the same density of overlapping initiatives in procurement and operational cooperation. The comparatively lower urgency around territorial defence means there is less pressure to converge on shared priorities.

Defence clusters will almost certainly be the driving force of Europe’s defence build-up.

Another strength of minilateral formats is their flexible membership, which allows Europeans to sidestep institutional constraints. Member States vary in their appetite to cooperate on defence matters and may be willing to work together in some cases but not in others. At the same time, several major players in European security – Ukraine, Norway and the UK – are not EU members. Small groups allow for deeper cooperation between EU members and between EU and non-EU Europeans, at a pace and depth determined by their participants.

Of course, small groups also have limitations. The most obvious is that they are inefficient compared to more radical alternatives such as a unified procurement system or a single army — arrangements that appear politically unattainable for the foreseeable future. A second challenge is that there are often limits to how far cooperation can go in terms of integration, as each country needs to weigh the efficiency gains of closer integration against the risk of not being able to use some capabilities if partners are not cooperative. A third challenge concerns coordination and coherence. Cooperation often occurs organically rather than as a structured process. Although a plethora of cooperation initiatives exist in Europe, these do not form part of a structured effort to strengthen Europe’s defences and fill capability gaps. Finally, there is no guarantee that political and technical obstacles to cooperation can be fully overcome in small groups. The troubled Franco-German programme for a next generation fighter jet shows that political backing alone is not sufficient, especially in the most complex capability areas.

Despite these limitations, the unique strengths of minilateralism mean that defence clusters will almost certainly be the driving force of Europe’s defence build-up. Ideally, minilateral formats would function as incubators of deeper cooperation: initial participants establish structures and show that cooperation can work, with other countries joining later if they wish and if their needs align. The challenge for European policymakers is how to make the most of the potential of defence clusters. While there has been much emphasis on joint procurement of equipment, Europeans leaders should also seek to promote deeper cooperation in areas such as training, logistics and force integration, so that European armies can work together smoothly with a much smaller US contribution. The aim should be for Europeans to develop more durable multinational frameworks in which national units train – and if necessary operate – together. In some cases, this might mean that larger European armies will act as aggregators for the capabilities of their smaller counterparts, along the model of Dutch-German mechanised forces. In other cases, it may mean setting up new command arrangements, as with cooperation among the Nordic air forces. In all cases, individual countries will always retain the right to withdraw their forces.

How the EU can harness small groups

European countries have long relied on bilateral and minilateral formats to advance cooperation. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has added further momentum to this approach. The task now is to maximise the advantages of these flexible formats and ensure that the EU connects them into a more coherent framework. The formation of clusters is essentially a bottom-up process: the EU cannot engineer clusters where threat perceptions and requirements do not align. However, the EU can help identify areas of convergence and lower the practical and financial barriers to cooperation.

First, the EU can provide practical support for cooperation. Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) was intended to enable selective cooperation on capability development and force integration, but its results have been disappointing, with few projects delivering tangible capability or integration outcomes. Nonetheless, PESCO may still serve as a useful framework for cluster-based cooperation if underpinned by political will, urgency and aligned requirements. The EU can also provide dedicated funding, as it is already doing through a range of instruments such as Security Action for Europe (SAFE) and the European Defence Industry Programme (EDIP), which respectively provide loans and grants to help Member States acquire specific capabilities. Funding can help catalyse progress in filling Europe’s most urgent capability gaps. A third avenue is training: the European Defence Agency (EDA) could facilitate multinational training programmes and help establish centres of excellence in priority capability areas – as it has done for helicopter training. To strengthen interoperability, the EU’s Rapid Deployment Capacity could conduct more regular and ambitious exercises.

The speed and depth of cooperation is ultimately in the hands of Member States.

Second, the EU can help coordinate efforts by connecting different cooperation clusters and identifying opportunities for cooperation. It already has a range of tools at its disposal, such as the EDA’s Coordinated Annual Review on Defence, and the upcoming Annual Defence Readiness Reports that the Agency will also prepare. To provide a meaningful picture of Europe’s capabilities, these assessments should also include the contributions of key non-EU European defence partners; otherwise they risk presenting an incomplete view of Europe’s defence posture.

The EU’s ability to coordinate and deconflict the activities of different clusters would be enhanced if representatives of EU institutions, such as the European External Action Service (EEAS) and the EDA, were invited to attend political and technical meetings of defence clusters on a regular basis. This would allow the EU to suggest ways to promote coherence, reduce duplication and align different initiatives. A partial model may be found in the Ukraine Defence Contact Group, which has helped coordinate the efforts of multiple capability-focused coalitions by providing a common forum for information-sharing, task allocation and deconfliction. These are functions that EU institutions could perform more systematically for European defence cooperation.

Third, the EU could support operations by ad hoc coalitions. In the event of a post-ceasefire mission in Ukraine, the EU could establish a parallel mission with a complementary mandate, to which Member States not willing to participate in the military mission could contribute. This could for example involve expanding the EUMAM training mission for Ukrainian forces and moving its training efforts to Ukrainian territory(6). The EU mission and the coalition of the willing could conceivably also cooperate on logistics. The net effect would be to increase the efficiency of European efforts and to allow all Europeans to contribute in the manner with which they are most comfortable.

Defence clusters can help Europeans strengthen their capabilities quickly and effectively. The speed and depth of cooperation is ultimately in the hands of Member States. What the EU can do is support defence clusters financially and practically, and help connect them to each other, turning a patchwork of initiatives into a stronger European defence ecosystem.

References

* The author would like to thank Alessandro Vitiello for his valuable research assistance.

1. Scazzieri, L., ‘Towards an EU “defence union”?’, Policy Brief, Centre for European Reform, 30 January 2025.

2. Besch, S., Brown, E. and Uzan, R., ‘Rebalancing the transatlantic defense-industrial relationship: regional pragmatism in Northeastern Europe’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 22 December 2025.

3. Ministry of Defence of Ukraine, ‘The role of partner nations in strengthening Ukraine’s Defence Forces through Capability Coalitions’, 27 December 2024.

4. Norwegian Armed Forces, ‘Four Nordic air forces fighting as one’, 3 March 2025.

5. UK Government, ‘New Coalition of the Willing headquarters as leaders step up support for Ukraine’s immediate fight’, Press release, 10 July 2025.

6. Spatafora,G., ‘Training soldiers in Ukraine: Creating conditions for a just end to the war’ in Everts, S. and Zorić, B. (eds.), ‘10 ideas for the new team: How the EU can navigate a power political world’, Chaillot Paper no 185, EUISS, September 2024.