- China is systematically embedding itself in global renewable energy supply chains, connected devices and European energy system operators. In an unstable geo-

political environment characterised by weaponised dependencies, this risk has become unacceptable. - The EU must reconcile its renewable energy ambitions with the risks of over-

dependence on China. This requires targeted public procurement for defence-related needs, notably in solar PV, alongside selective trade restrictions in wind power and safeguards for emerging green hydrogen and synthetic fuel industries. - There is a growing cyber threat linked to Chinese-made solar inverters, underscoring the need for a ‘Made in Europe’ requirement for critical infrastructure. The EU should phase out and exclude Chinese components from Connecting Europe Facility for Energy (CEF-E) funded cross-border projects.

China is already inside Europe’s energy system, embedded in both the physical infrastructure and connected devices. While China is a useful actor in the global energy transition, the EU should accelerate efforts to reduce the risks related to the presence of Chinese products and services, especially in military-relevant energy infrastructure.

The risks to the energy system are clear. Beijing has already demonstrated its willingness to weaponise industrial dependencies, especially in critical raw materials. It is increasingly acting against European interests through close alignment with Russia in its war against Ukraine and in hybrid attacks on EU countries. Meanwhile in the cyber domain, Chinese hackers such as Volt Typhoon have shown that they are preparing for attacks on critical infrastructure by establishing footholds within key systems.

Nevertheless, until now, Europe has underutilised its considerable strengths and expertise in the energy system as well as several powerful de-risking tools, from public procurement to trade measures. It should leverage these assets with far greater resolve.

Commanding renewables

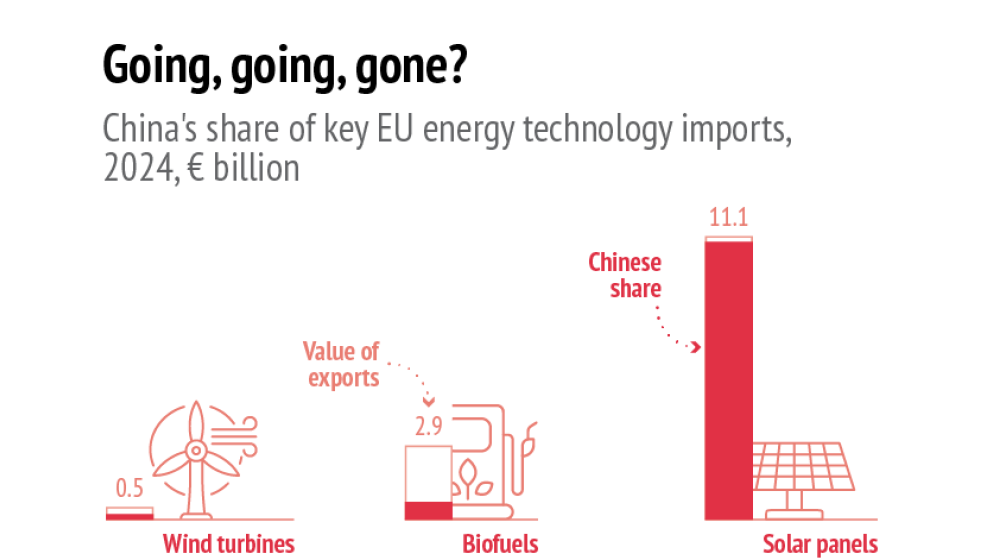

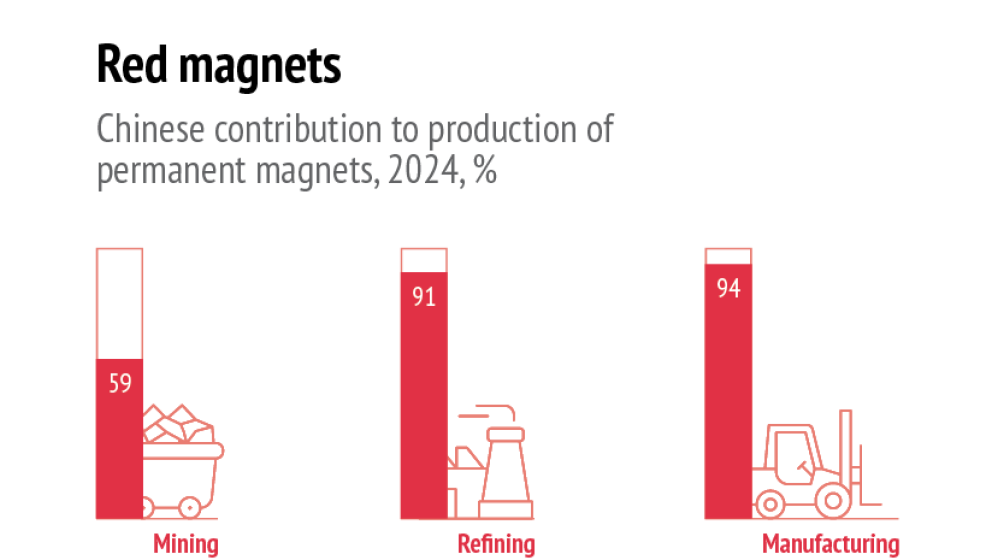

China has explicitly pursued an industrial strategy that prioritises green energy as a pillar of economic growth, most recently through its 14th five-year plan, with the forthcoming 15th expected to reinforce this trajectory. This strategy is most evident in China’s dominance in Solar PV supply chains. By 2023, it controlled 98% of all global solar PV wafer production(1). This near-total market dominance gives China a stranglehold over the rest of the solar supply chain, even though it produces ‘only’ 85% of solar PV panels worldwide(2). Solar PV accounted for 597GW of new capacity added globally in 2024, almost three times the EU’s total gas-fired power capacity(3).

A similar pattern is evident across other clean energy technologies. By 2024, China produced 70% of all wind turbines globally, albeit mostly for domestic use(4). This reflects broader efforts to establish dominance in other future industries where Europe initially led, including green hydrogen and sustainable aviation fuels (SAF).

In a familiar playbook, the Chinese government set out a hydrogen strategy for 2021-35 aimed at decarbonising its domestic hydrogen market, the world’s largest. Chinese electrolyser costs fell by 40% between 2022 and 2024 as industrial producers dramatically scaled existing technologies, helped by abundant and cheap green energy.

By 2024, China had become the world’s largest producer of hydrogen electrolysers and the biggest single producer of green hydrogen. It is preparing to expand its export markets, including for related products such as a first shipment of green steel produced with hydrogen delivered to Italy in July 2025(5). In SAF, China is building on a long-established recycling infrastructure to convert used cooking oils into biofuels. In October 2025, it approved three new biofuel refineries intended primarily to export SAF to Europe(6). It has also expanded its footprint in synthetic fuel production, often by incentivising leading European firms to set up production in the country. Green fuels, including synthetic fuels and hydrogen, are expected to play a central role in the 15th five-year plan(7).

From investment to influence

Chinese state companies have also been investing in European utilities and grid operators, which carries similar risks – especially for transmission system operators (TSOs). Chinese state-linked companies now own significant stakes in the system operators REN (Portugal), Terna through CDP Reti (Italy), Creos (Luxembourg), Enermalta (Malta) and IPTO/ADMIE (Greece). Broader efforts to acquire stakes in system operators in Spain, Germany and the UK have been blocked by national governments, often on national security grounds(8). While there has been a considerable drop-off in investments by Chinese energy companies since the late 2010s, as well as greater scrutiny of Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in general, the legacy of Chinese involvement in the energy system persists.

This raises three problems. Firstly, as investors, Chinese companies gain a say over the strategic direction of TSOs at a critical moment, especially for Europe’s grid operators. The Commission’s grids package, presented in December 2025, foresees billions of euros of investment in European energy infrastructure(9). At REN, for example, the State Grid of China (SGCC) holds a 25% stake which grants it voting rights and influence over key strategic decisions.

Secondly, despite some safeguards in EU regulations, TSOs have access to crucial information about the functioning of the energy system not only in their own countries but also across the EU through the European Network of TSOs (ENTSO-E/G). Any leakage of such data would represent a major weakness for Europe’s energy system as a whole. Moreover, for Europe’s energy market to function at its best there needs to be a considerable degree of trust. This trust is undermined by the geopolitical risks posed by Chinese investments, as illustrated by the controversy surrounding CDP Reti’s attempted acquisition of 50Hertz in Germany. Even the mere presence of Chinese companies can erode trust and indirectly affect European energy cooperation.

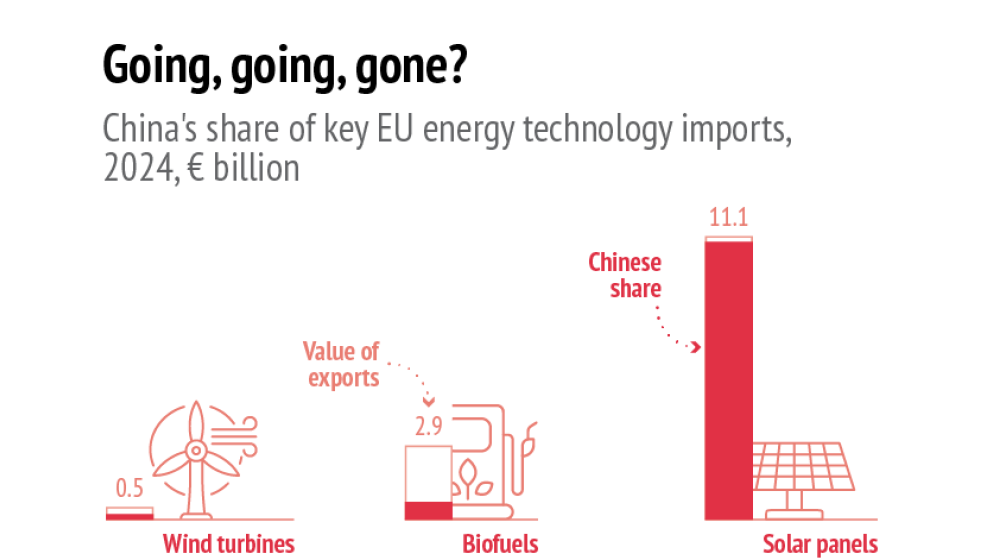

Thirdly, the supply chain risk could be exacerbated by the presence of Chinese investors in the energy system which creates a preference for Chinese-made grid equipment. The State Grid of China and China Southern Power Grid, both state-owned enterprises and major investors in Europe’s energy grid, are subject to domestic procurement rules favouring Chinese providers. In practice, both have consistently favoured Chinese grid technology firms, including Huawei and XD electric, over European competitors in their domestic infrastructure projects(10).

Controlling the on-off switch

In addition to its growing dominance in the industrial goods needed to power the energy transition, China has also moved to control a growing share of the global supply of connected devices within the energy system. This has been especially evident in solar inverters, which convert generated power into useable electricity. Chinese providers, most notably Huawei and Sungrow, account for an estimated 55% of all solar inverter shipments worldwide(11). As with Chinese dominance in clean energy generation, this poses a supply chain risk. However, it goes further. In 2025, US analysts identified unexplained components in Chinese-manufactured inverters designed to allow backdoor communication with solar installations(12). In May 2025, EU officials voiced similar concerns, with a group of MEPs calling for the exclusion of high-risk vendors from the energy grid, noting that Huawei alone had a 115GW share of the EU market(13). The risk in both cases was that Chinese companies – and ultimately the Chinese state – could gain remote access to European solar panels, either triggering a surge or removing capacity all at once. Volt Typhoon’s activities in the US have raised similar concerns, highlighting comparable risks for European energy systems. The MEPs cited the Spanish example, where the sudden loss of 2.1GW of capacity was enough to trigger a cascade effect and cause a blackout in that country in April 2025. The major risks therefore are routinely connected to a broader failure of the electricity system through a voltage collapse or surge.

The risks posed by Chinese inverters to Europe’s energy system echo earlier concerns about Huawei’s role in 5G telecoms networks. There do appear to be legitimate grounds for concern about Chinese components this time in the energy system. Solar Power Europe has noted that cybersecurity protocols within the EU, notably the NIS 2 directive, are sufficient for utilities, but do not apply to smaller generators such as rooftop solar panels. In effect, this means a cybersecurity risk in an increasingly relevant but vulnerable sector. For example, in the Netherlands, rooftop solar accounts for 15-16% of total electricity generation capacity(14). Considering that the EU also has its own substantial inverter industry, and that some services such as ‘scrubbing’ of inverters are available (and are already utilised by several European utilities), there appears little reason to maintain this risk. This is especially problematic for solar installations with military relevance, where Chinese technology is commonly used.

Some concerns about Chinese inverters do verge on industrial protectionism. Yet China’s solar industry is increasingly global, exposing it to strategic communications risks should it be perceived as exercising remote control over sovereign energy systems. Equally, some of the risks associated with Chinese inverters, such as internet connectivity and their reliance on cloud servers, also apply to European-made inverters, underscoring that cybersecurity, rather than country of origin alone, is the central issue. Such concerns are also relevant to other connected devices that increasingly underpin the energy system, from smart meters to smart heating. Nevertheless, additional risks persist, as Chinese producers are legally obliged, under article 7 of China’s 2017 National Intelligence Law, to share product information with the state.

Recommendations

China’s involvement in Europe’s energy system spans multiple domains, requiring a coordinated response that draws on a range of policy tools and institutions to reflect the dual nature of energy as both a structural enabler and a source of geopolitical risk.

The physical components of the energy system produced mostly in China, including solar modules, permanent magnets and grid-scale batteries, pose clear supply-chain risks for the EU. However, once deployed within the EU such assets become functional contributors to the EU’s energy security. With cheap, abundant and renewable energy, the EU will be better placed to secure its competitiveness in future technologies, including hydrogen and SAF, where high energy prices remain a major barrier to entry.

Nevertheless, in sensitive areas such as military energy infrastructure, public procurement tools should be employed to ensure a minimum level of production within the EU to service high-risk sectors. Public procurement tools would also be most effective if paired with targeted investment in R&D, such as in perovskite solar cells, focusing on specialised production and future technologies rather than directly competing with Chinese industrial dominance.

The EU has considerable strengths at its disposal in the size of its market, which it should be much more active in employing against China. In areas where Europe remains competitive and where its market weight is vital to Chinese exporters, restrictive trade measures should be enforced at both national and EU level.

A consistent security premium should be applied to wind turbines, as is already the case in some Member States. With China already built into the supply chain through its dominance of permanent magnets, efforts to ensure the competitiveness of the European wind industry will have to move in parallel with measures to ensure supply of critical minerals in Europe. This dependency can be managed, especially by building on Europe’s strong recycling capacity for magnets and batteries.

For hydrogen and SAF, the EU is already a major market and will become a more important one in the future. Given their significant military relevance, supply chains in these sectors must not become dependent on China. In these areas, the Commission should deploy robust protective trade measures to shield Europe’s nascent industries.

Regarding inverters, therefore, there are clear risks both for the supply chain and also from potential cybersecurity infiltration. However, both risks are manageable. There is a strong argument for a ‘made in Europe’ strategy for inverters, an area where the EU already has a strong market share spread over several Member States. For high-risk sectors, including grid-scale projects and military applications, such inverters should be employed as a matter of policy, even at higher cost. By contrast, some parts of the solar sector present lower levels of risk, allowing greater discretion over whether to use Chinese-made – and potentially vulnerable – inverters. For example, where generation is kept separate from the grid and risk is borne entirely by the user, who can make a choice between short-term cost and long-term disruption. For installations connected to the grid, such as rooftop solar, grid operators should be responsible for assessing the potential risk to the system and for setting clear eligibility criteria for solar installations linked to the grid via inverters.

The EU should adopt a coordinated approach to define a single EU-wide strategy for future Chinese investment in TSOs. Individual Member States should also outline clear procurement guidelines for Chinese energy technologies, particularly in military-relevant energy infrastructure. Given the scale of current grid expansion, the risks of infiltration and influence over decisions on future planning are simply too high. The Commission should therefore incorporate security criteria into future Connecting Europe Facility for Energy (CEF-E) funding to limit the involvement of Chinese actors.

References

1. IEA, Trends in Photovoltaic Applications 2024, 2024.

2. Ibid.

3. Solar Power Europe, ‘New report: World installed 600GW of solar in 2024’, 6 May 2025.

4. Bloomberg NEF, ‘Chinese manufacturers lead global wind turbine installations’, 17 March 2024.

5. Canary Media, ‘China looks to supercharge green hydrogen as US pulls back’, 28 October 2025.

6. ‘China allows more biofuel firms to export green aviation fuel, sources say’, Reuters, 17 October 2025.

7. FCW, ‘China targets green hydrogen, ammonia and SAF in energy policy shift’, 12 November 2025.

8. GMF, ‘Chinese state-owned operator tried to purchase a 20% stake in the regional transmission system operator, 50Hertz’, 27 July 2025.

9. European Commission, ‘Commission proposes upgrade of the EU’s energy infrastructure to lower bills and boost independence’, 10 December 2025.

10. Yicai Global, ‘Chinese power equipment suppliers win major state grid procurement deals’, 12 March 2025.

11. Wood MacKenzie, ‘Global PV inverter shipments grew by 10% in 2024 to 589 GWac’, 10 July 2025.

12. ‘Rogue communication devices found in Chinese solar power inverters’, Reuters, 14 May 2025.

13. European Parliament, ‘Toolbox to restrict risky photovoltaic (PV) inverters from European electricity grid’, Parliamentary question, 15 May 2025.

14. CBC. ‘The Netherlands generates way more solar power than Canada. Here’s how they do it’, 2 July 2024.