It may appear almost unseemly to focus on Afghanistan’s potential as a hub of regional connectivity considering that close to half of its population is currently facing food insecurity and reliant on foreign humanitarian assistance for survival (1). Meeting the immediate humanitarian needs of the Afghan people is clearly an urgent priority and international bodies and external powers, including the European Union, have an obligation to support them. Having endured four decades of armed conflict, and experienced two foreign military interventions, the country saw the re-emergence of the Taliban as its de facto rulers following the fall of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan on 15 August 2021, after the withdrawal of US troops and the end of the NATO-led Resolute Support Mission (RSM).

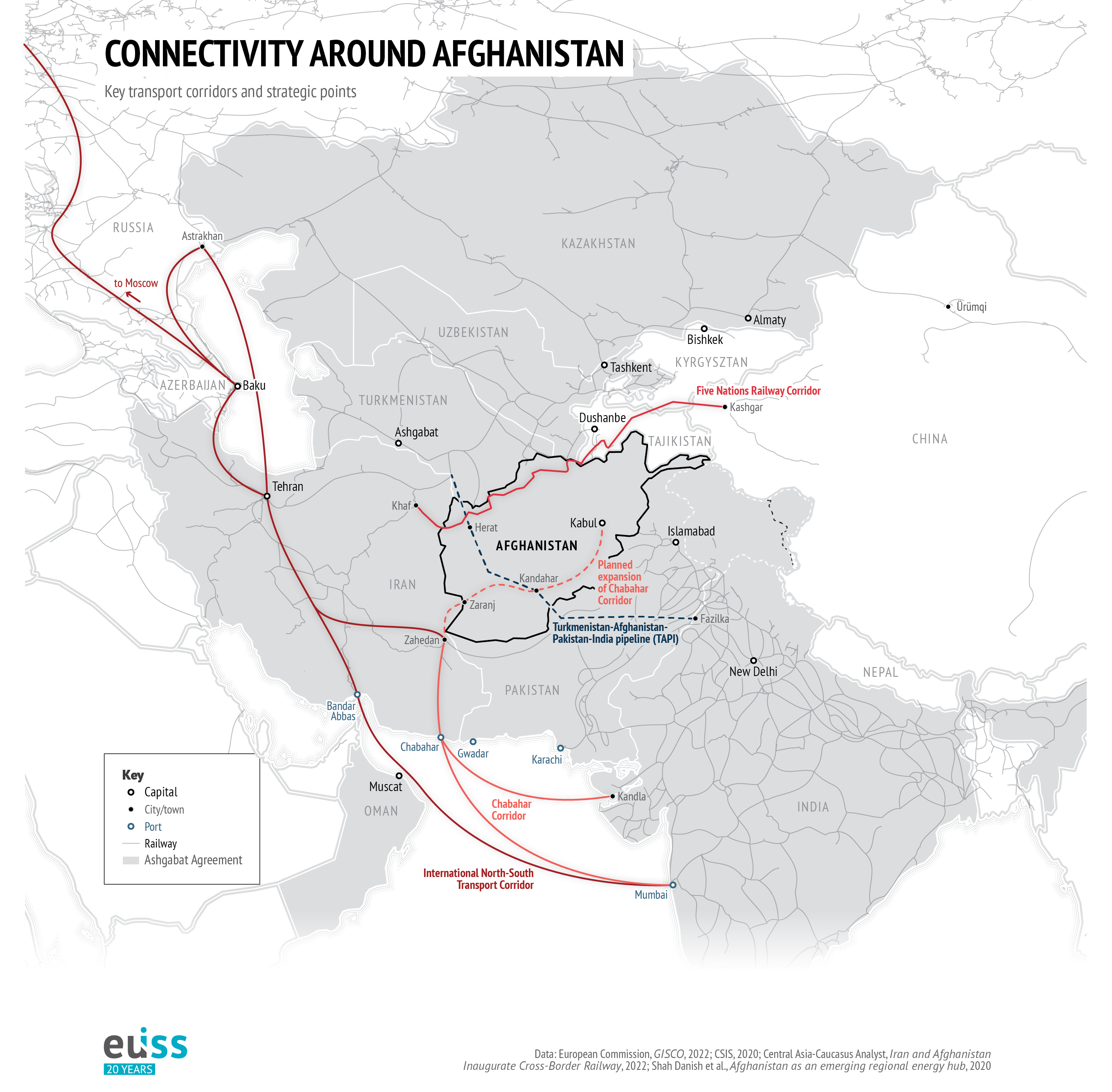

The aim of this Brief is to understand the implications of Afghanistan’s geostrategic position for wider regional connectivity against the backdrop of broader tectonic shifts taking place in the world order between international, rising and regional powers. Broader security and geo-economic implications (2) arising from the vacuum left by the withdrawal of US and NATO troops from Afghanistan will also be considered. Despite being a landlocked country, Afghanistan lies at the crossroads of East Asia, South Asia, Central Asia/Eurasia and the Middle East. The Middle East and Eurasia, both part of the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), remain strategic priorities for Europe (3).

Afghanistan’s geostrategic importance derives from its unique geographical location as well as from its rich endowment of natural resources. From a geopolitical standpoint, the country can be seen as the meeting point of the regional architectures of China, Russia, India and Iran (4). This Brief explores the geo-economic dynamics of key regional and rising powers and how this translates into economic and infrastructure connectivity around Afghanistan. This geographical area includes ‘greater Central Asia’ (5), as well as Turkey and India. It is no coincidence that the Taliban visited Islamabad, Tehran, Moscow, Ashgabat and Tianjin (China) for talks with officials soon after their takeover in mid-August 2021 (6). It should also be noted that both China’s Foreign Minister Wang Li and the Russian Special Envoy to Afghanistan visited Kabul in the spring of 2022.

Contributing to this puzzle are myriad connectivity initiatives that have emerged globally; ‘connectivity’ having become the new ‘buzzword’ (7). The wide-ranging Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) and the EU Global Gateway have received widespread international attention. There are also inter-regional initiatives such as Russia’s ‘Greater Eurasian Partnership’, the Lapis Lazuli Corridor and the Ashgabat Agreement that are pertinent to Afghanistan (8). The grid of existing Eurasian corridors can be further complemented by a North-South web of routes, encompassed by the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), which links India with Russia, via Iran. Such an extensive network could interconnect the four poles of Europe, China, India and Russia (9).

This further gives prominence to ports in Iran and Pakistan, which are gaining geostrategic significance beyond their immediate neighbours. Western sanctions imposed on Moscow, in response to the war in Ukraine, have hindered the flow of trade across Eurasia. This has, in turn, sparked a growing interest in Pakistani and Iranian ports to guarantee alternative trade routes for China, Central Asia and India via the Persian Gulf, the Gulf of Oman and the Arabian Sea. This has made Afghanistan an even more crucial transit corridor.

External stakeholders share a common concern: the quest for stability in Afghanistan.

For the connectivity potential around Afghanistan to materialise, however, external stakeholders share a common concern: the quest for stability in the country. Containing the Islamist threat, supporting counter-terrorism activities and clamping down on criminal and illicit trade networks, remain shared and highly challenging objectives. Stability will only come to Afghanistan with support from its immediate region, the bulk of which is composed of countries antagonistic to the West (10). The likes of China, Iran, Russia, Pakistan and Turkey are becoming increasingly impervious to the influence of Western powers in the current geostrategic context. This is the case even though they worked jointly with Western powers in providing assistance to Afghanistan throughout decades of attempts at peace negotiations (11).

This analysis starts off with a brief overview of Afghanistan’s fragile situation. The takeover of power by the Taliban took place over a year ago; understandably, attention is currently mostly focused on security and governance-related issues within Afghanistan. Notwithstanding, it is worth exploring the country’s potential as a transit route for both existing and planned regional and inter-regional connectivity projects and examining how this could be used to exert leverage over the de facto Taliban regime. The role of immediate neighbours, as well as of more distant neighbours and key rising powers, is explored. Finally, opportunities for the EU to engage with regional players and tap into Afghanistan’s connectivity potential as the Union rolls out the Global Gateway initiative are addressed.

A struggling economy but a potential transit hub?

With the withdrawal of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in 2014 there were hopes that stronger Afghan ownership and locally-driven economic growth would materialise in Afghanistan. It was vainly hoped that such growth could be generated by tapping into the immense economic potential represented by Afghanistan’s abundant natural resources including gas, oil, copper, iron, other minerals and rare earths. In fact, the country’s petroleum and liquid gas reserves are estimated to be sufficient to cover Afghanistan’s energy consumption for years to come (12). Ironically, Afghanistan currently has to import both refined petroleum and electricity to meet its needs. In fact, it imports 73 % of its electricity from its Central Asian neighbours, despite the fact that the Taliban cannot pay for the electricity supplies from these countries (13). This explains the existence of multiple power transport projects from Central Asia to South Asia.

The opium trade remains a key source of revenue for the country. After a temporary decline in 2018, the opium economy in the country currently accounts for 6-11 % of Afghan’s GDP, while Afghanistan accounts for 85 % of global opium production (14). Post-August 2021 prices for opiates have risen to compensate for the sudden suspension of development assistance – now only focused on off-budget humanitarian aid – as well as the freezing of offshore Afghan government assets.

Since the Taliban takeover, transactions between Afghan and international banks have been halted due to fears of money laundering and terrorist financing, against the background of already existing United Nations Security Council (UNSC) counter-terrorism resolutions (Resolution 1988 from 2011 and Resolution 2255 from 2015) imposing an assets freeze, a travel ban and an arms embargo on individuals, groups, undertakings and entities associated with the Taliban. Since 2021, the economy has contracted by 20 %, although domestic revenue collection and exports are picking up, partly due to increased customs duties and a crackdown on corruption (15).

There are tentative signs of stabilisation and resilience in the Afghan economy, nonetheless. Last September a cargo train successfully completed its maiden journey on a multimodal road and rail route from the city of Kashgar in Xinjiang, China, to Hairatan in Afghanistan, bypassing Pakistan (16). According to the latest World Bank Private Sector Rapid Survey conducted in the country during June 2022, more than three-quarters of Afghan firms were operational, compared to two-thirds in November 2021 (17). Nevertheless, the reality on the ground continues to be defined by heightened food insecurity, rising unemployment, and lower international and domestic remittances. It is also expected that physical access to humanitarian assistance will be limited during the upcoming winter period (18).

International powers should aim to engage selectively with regional powers to tap into the broader regional potential for connectivity.

The Taliban continue to seek both domestic and international legitimacy, and it seems more likely that this will accrue to them through their pursuit of economic development than good governance practices. Thus, regional and rising powers could leverage connectivity to put pressure on the Taliban regime to comply with basic human rights obligations vis-à-vis ethnic minorities and women, such as ending violence and discrimination against them, and allowing women to join the labour force and girls to attend secondary school (19). International powers, for their part, should aim to engage selectively with regional powers to tap into the broader regional potential for connectivity.

A nexus of inter-regional connectivity

Afghanistan’s neighbours

When looking at connectivity around Afghanistan, it is important to see it in the wider context of a ‘greater Central Asia’. This section explores the role of neighbours, regional and rising powers in attempts to promote inter-regional connectivity.

Pakistan remains a key partner, large due to political and ethnic-based links with the ruling elites in Afghanistan, particularly with the Taliban de facto authorities. From an economic standpoint, Pakistan has historically been Afghanistan’s biggest trading partner, even if recently overtaken by India as an export destination; Iran and China have taken the lead in terms of Afghanistan’s imports (20). Hence the importance of the Afghan Pakistan Transit Trade Agreement (APTTA) from 2010, which allows both countries to use each other’s airports, railways, roads and ports. The implementation of the agreement has been inconsistent on both sides, however. This has led Afghanistan to focus less on the Gwadar and Karachi ports in Pakistan and to redirect shipments towards the Iranian ports of Bandar Abbas and Chabahar.

Both Afghanistan and Pakistan are actively pursuing regional cooperation to develop their energy resources, and Central Asia can play a key role in this domain. As long identified by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), there is an energy-rich Central Asia and a power-poor South Asia. Thus, the Central Asia South Asia (CASA) – 1000 Project is designed to deliver electricity from the hydropower plants located in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to Afghanistan and Pakistan during the summer season (21). The European Investment Bank (EIB) has contributed funding to this project (22). There is an additional Central Asia South Asia Regional Electricity Market (CASAREM) Project from 2014 that encompasses the Turkmenistan-Uzbekistan-Tajikistan-Afghanistan- Pakistan (TUTAP) power interconnection project. The initiative aims to connect Central Asian countries to a unified Afghanistan grid that can further re-export hydroelectric power to Pakistan (23).

Beyond its interconnections with its immediate neighbours, Afghanistan is linked to China via the Sino-Afghan Special Railway Transportation (SARTP) initiative connecting China and northern Afghanistan, which was inaugurated in 2016 andrecently successfully reactivated. In addition, there is the Five Nations Railway Corridor that connects China to Iran via Afghanistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, delayed due to renewed US sanctions on Iran imposed in 2018 and the conflict situation in Afghanistan. There is also an Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO) Transit Transport Framework Agreement (TTFA) ratified in 2006 among landlocked states with substantial outside financial support, including from the EU, that includes Afghanistan and the majority of its neighbours (24).

The Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) Pipeline, initially known as the Trans-Afghanistan Pipeline – excluding Pakistan and India - has been planned since the mid-1990s, soon before the Taliban took power in 1996. With the US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 and widespread instability in the country, construction halted until 2008 when a new deal was struck (officially signed in 2010) by Pakistan, India and Afghanistan to buy natural gas from Turkmenistan. The additional stretch to Pakistan and India adds another conflictive layer to the initiative, considering the troubled bilateral Indo-Pakistani relationship. The pipeline has been completed in Turkmenistan but construction in Afghanistan has been stalled due to decades of fighting between the Afghan government and the Taliban. Since returning to power in August 2021 the Taliban have promised to continue construction of the pipeline (25).

Regional and rising powers around Afghanistan

Another development worth mentioning is the way in which Iran and Turkey are seeking to play an increasingly prominent role along the borders of West Asia. The Islamic dimension should not be underestimated, considering that Afghanistan is surrounded by majority Muslim-populated countries, all of which are members of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). The OIC set up a Humanitarian Trust Fund for Afghanistan, togetherwith the Islamic Development Bank, as early as in December 2021 under Pakistan’s auspices. This is running independently from the UN-managed Afghanistan Humanitarian Fund, which has Western countries as top donors (26).

Ankara has been advocating in favour of providing diplomatic recognition to the Taliban since March 2022, having left its diplomatic mission open in Kabul and expanded its in-country missions to Mazar-e Sharif. It has long sought to further its ambition to foster the emergence of a unified Turkic world in Central Asia through its involvement in Afghanistan, thus enhancing its foothold in South and Central Asia, despite lacking the political and security clout that it seeks (27). It was, however, in Doha that the Taliban chose to open their first overseas political office in 2013. Qatar has proven to be a crucial broker in peace negotiations between the Taliban and the US Administration, resulting in the February 2020 Peace Agreement.

Iran has grown into a key economic and geostrategic partner for Afghanistan and for Eurasia more broadly. Tehran launched official negotiations on a free trade agreement (FTA) with the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) as far back as in 2020 (28). Iranian ports have become crucial to access sea routes across the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman, not only for Afghanistan, but also for the Central Asian Republics (CARs) whose commodity exports transit through Afghanistan. The launch of the INSTC and the Ashgabat Agreement are proof of this. Tehran is furthermore growing closer to China geo-economically, as the 25-year China-Iran Strategic Cooperation Agreement signed in May of 2021 shows. Beijing was happy to support Iran’s inclusion as a new member of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) bloc in the framework of this year’s Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) Summit in Samarkhand.

India, allegedly a ‘like-minded’ partner and a key counterweight to Chinese influence in the region, has developed a strong interest in the Iranian ports of Chabahar and Bandar Abbas. In fact, New Delhi has committed to constructing container and multi-purpose terminals at Chabahar port, with the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) as far back as in 2015 (formalised in 2016). The project also includes the Chabahar-Zahedan railway link to the Afghan border. Interestingly, the Trump Administration made sure to waive its 2018 sanctions on Indian investments in Chabahar following Iran’s withdrawal from the 2015 nuclear deal, invoking the importance of Chabahar as a lifeline for Afghanistan and, more importantly, its strategic partnership with India.

New Delhi realises how Chabahar port can serve as a link to the INSTC that connects the Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf to the Caspian Sea via Iran; it has proven to be much more cost- and time-effective than the Suez route. Eventually, this would result in Mumbai and Moscow being directly connected. India’s formal accession to the Ashgabat Agreement in 2018 shows its intent to further connect towards Eurasia via the CARs. Chabahar will effectively become a crucial two-way transit point between the Middle East, possibly Europe, and Afghanistan and Central Asia (29). Geostrategically, Chabahar and the INSTC are seen as a direct counterbalance to Beijing’s China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which is described in the section below.

Can China and Russia fill the vacuum?

The US presence has tangibly diminished following its withdrawal from Afghanistan, the closure of NATO’s Northern Distribution Network (NDW) and several US airbases in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, respectively (30). The international legitimacy of the United States, and that of NATO, following their hasty withdrawal from Afghanistan, has also been dented. This has led to speculation as to whether the vacuum left behind may open the door for increased Chinese and Russian influence in post-NATO Afghanistan, as well as the broader implications for a ‘greater Central Asia’. Some analysts argue that a distribution of roles between Russia, as key security provider, and China as leading bankroller and connectivity partner, will likely take place. Others argue that both countries remain primarily focused on security, that is, preventing terrorism and religious extremism from spreading within and outside Afghanistan.

China sees both an opportunity and a threat in the US withdrawal from Afghanistan. Beijing is a firm supporter of economic development as a means of achieving greater security and stability; Afghanistan is proving particularly challenging, however (31). Beijing has been very pragmatic in its engagement with Afghanistan, establishing relations with all political actors. Last spring Beijing organised the third Foreign Ministers’ Dialogue to promote coordination and cooperation among Afghanistan’s neighbouring countries, with the Acting Foreign Minister of the Afghan Interim Government attending (32). An MoU was signed in the framework of the BRI between China and Afghanistan as far back as in 2016, with limited tangible advances thus far, although a direct railway connection exists between Xinjiang and northern Afghanistan. Moreover, China sees Afghanistan as a key transit country in a broader China-Central Asia-West Asia Economic Corridor (CCAWEC), as noted when Beijing hosted this spring’s conference with Afghanistan’s neighbouring countries on the country’s economic reconstruction (33).

The inauguration of CPEC in 2015 has provided Beijing with a solid platform for expanding connectivityin South Asia via Pakistan, with potential further linkages to Iran via Afghanistan. CPEC uses the Pakistani Arabian Sea port of Gwadar as a base. It aims to transform the logistics route from China’s Xinjiang region to Gwadar. The Corridor has not been devoid of controversy in Pakistan, amidst claims of inequitable economic development and resource distribution across the country (34). As in other smaller Asian countries, such as Sri Lanka or Bangladesh, the BRI is perceived as unprofitable for Pakistan: there is a widespread belief that for Islamabad geopolitical interests take precedence over the economic benefits to the local population.

Islamabad has had to set up a special Security Division with troops to protect CPEC investments in Pakistan due to attacks on Chinese citizens by ethnic Baloch and Sindh separatists (35); more recently, Chinese citizens have also come under fire from the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and from alleged Uyghur militants in the country (36). There are strong suspicions that the port of Gwadar, a ‘strategic strongpoint’ situated along Beijing’s Maritime Silk Road, may serve a dual civil-military use, to India’s concern. China has officially denied having any military intentions behind CPEC, however. Yet the Chinese military’s presence in Gwadar is increasing (37).

Within the broader neighbourhood, Beijing has been keen to project itself as a reliable partner in Central Asia, as opposed to an unreliable United States. In doing so it has relied on the rollout of the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB), the Central Asian component of the BRI. Despite initial reluctance on the part of Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan towards foreign investments, the construction of the Central Asia-China pipeline network has been of key importance for Beijing’s consolidation of the initiative. The development aspect of the SREB has been particularly appealing to Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, both of which are dependent on Russia’s military and security assistance. Uzbekistan has engaged in antiterrorism cooperation with China while Kazakhstan, the largest economy, has historically been a significant supplier of energy resources to China (38).

Russia, for its part, views a ‘Greater Eurasian Partnership’ as ‘an alternative to the Western-centric model’ (39). In fact, Russia sees complementarities between its own vision and the BRI. However, it also sees the need to counterbalance the BRI via the EAEU connection to Iran, India and Southeast Asia (40). During the recent SCO Summit in Samarkand, Moscow criticised Washington for its imposition of sanctions on regional powers – namely Iran and Russia – and warned against the danger of further alienation from the West. Such anti-Western rhetoric could lead to the perception of an increasingly consolidated Pakistan-China-Russia-Iran axis, with India walking a tightrope between the so-called ‘like-minded’ and ‘revisionist’ powers. Such a perspective is somewhat unnuanced, however. The reality is much more complex with a wide range of stakeholders engaged with Afghanistan, as the presence of Indian, Saudi and Turkish delegates during Russia’s regional ‘Moscow Format of Consultations on Afghanistan’ shows. Nevertheless, Zamir Kabulov, Russia’s Special Envoy to Afghanistan, has advocated in favour of the United States and its allies’ unblocking Afghanistan’s national financial assets (41).

Opportunities for the EU?

The EU has historically adopted a principled approach towards Afghanistan. Following the Taliban’s takeover, the EU has continued to provide substantial humanitarian assistance, while distinguishing between the needs of the Afghan people and those of the de facto Taliban government. The EU requires Afghanistan to adhere to the international treaties to which it is a State Party by upholding and protecting basic human rights, as well as guaranteeing the inclusive participation and representation of citizens in governance processes (42). Bearing in mind this difficult equation, a set of recommendations is provided below on how the EU can tap into connectivity initiatives around Afghanistan and potentially enhance its leverage vis-à-vis the Taliban regime.

Firstly, the EU is increasingly keen to move away from its role as a ‘payer’, aiming to become a more relevant global ‘player’ with strategic autonomy (43). To counter the current vacuum left by the United States and its NATO allies, the EU should seek ways of engaging regional stakeholders located in Afghanistan’s immediate geostrategic environment, such as the CARs and India. While the EU has limited regional leverage, it can seek to play a bigger role in geo-economic terms. This may currently involve doing more around rather than inside Afghanistan. The EU sees the emergence of a secure and stable Afghanistan as crucial for the development of the broader Central Asian region. Religious extremism, terrorism, and refugee flows combined with illicit and criminal trade networks stemming from Afghanistan are also matters of concern for the CARs (44).

Secondly, the CARs constitute an ideal testing ground for the EU to roll out its Global Gateway as demonstrated by the first EU-Central Asia Connectivity Conference recently held in Uzbekistan. The emphasis has been on digitalisation, transport and trade facilitation, energy and water resources (45). In fact, the EU has long had a strategic interest in the five CARs: the EIB set up an Investment Facility for Central Asia (IFCA) to develop better energy and transport infrastructure, as far back as in 2010. Therecent MoU signed between the EU and Kazakhstan, with whom it has just upgraded its bilateral relations to a Strategic Partnership, is illustrative of this too (46). Both partners have agreed to the production and export of green hydrogen and raw materials to the EU (47). The EU has further concluded an Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (EPCA) with Kyrgyzstan and is currently in the process of negotiating one with Uzbekistan (48).

Thirdly, including countries in the Caucasus, such as Azerbaijan, could further expand the potential of European connectivity initiatives into Eurasia. There is now a strong interest in expanding the Southern Gas Corridor with a view to transporting increased volumes of gas from Azerbaijan to Europe, as part of the EU-Azerbaijan MoU on a Strategic Partnership signed in July of this year (49). The existing TRACECA inter-governmental initiative from the late 1990s can provide the EU with a good starting point towards further connecting Europe with Asia via the Caucasus and Central Asia, also as part of the Global Gateway.

Another potential entry point into Eurasia is expanding the Trans-European Network for Transport (TEN-T) eastwards, as proposed in the EU’s ‘Connecting Europe and Asia: Building Blocks for an EU Strategy’ (50). TEN-T comprises clear priorities and standards to promote cross-border and multi-modal transport, that is, a combination of rail, sea and inland waterways (51). One of the EU’s main concerns is to make transport connectivity more secure across the TEN-T network, also vis-à-vis its Asian partners. The EU is keen to ensure that there is adequate security provision along its trade routes, where transnational organised crime, illicit smuggling and trafficking, and attacks on transport and energy infrastructure – including cyberattacks – remain a risk. Following the 2019 review, the aim is for the TEN-T network to further allow for the movement of military forces (troops, assets and equipment) within and beyond the EU (52). This is illustrative of how the quest for a ‘Geopolitical Europe’ is further trickling down into EU connectivity.

Finally, the growing relevance of Iranian and Pakistani ports leading into the Persian Gulf is key. Interestingly, the EU currently identifies maritime security and cooperation, particularly across the Indo-Pacific, among its core strategic areas. In particular, the current new focus is on the north-western Indian Ocean and Coordinated Maritime Presences (CMP), as the deployment of a European-led Maritime Surveillance Mission in the Strait of Hormuz (EMASOH) shows (53). This is where cooperation with India could be fruitful. New Delhi has obvious interests in ensuring maritime security across the Indian Ocean and sees the Iranian Chabahar port as a key geostrategic asset, as previously indicated. The broader geopolitical dimension of these ports is of crucial importance due to increased imports of oil from Gulf States, as well as the need to diversify transport routes from Central Asia beyond Russia, as noted earlier. This illustrates the wide range of options for the EU to unlock Afghanistan’s connectivity potential and thus expand the outreach of its Global Gateway.

References

1. FAO, Integration Food Security Phase Classification, ‘Afghanistan’, IPC Acute Food Insecurity Analysis, May 2022 (https://www.ipcinfo.org/fileadmin/user_upload/ipcinfo/docs/IPC_Afghanistan_AcuteFoodInsec_2022Mar_2022Nov_report.pdf).

2. Geo-economics has been defined as ‘the geostrategic use of economic power’. See: Wigell, M. and Vihma, A., ‘Geopolitics versus geo- economics: the case of Russia’s geostrategy and its effects on the EU’, International Affairs, Vol. 92, No. 3, 2016, pp. 605-627.

3. European External Action Service (EEAS), ‘European Neighbourhood Policy’, 29 July 2021 (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/european-neighbourhood-policy_en#:~:text=The%20European%20 Neighbourhood%20Policy%20(ENP,their%20mutual%20benefit%20 and%20interest).

4. Asey. T., ‘A house divided: Afghanistan neighbours power play and regional countries’ hedging strategies for peace’, Atlantic Council, 4 February 2021 (https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/southasiasource/a-house-divided-afghanistan-neighbors-power-play-and-regional-countries-hedging-strategies-for-peace/).

5. This term was coined by the US in the post 9/11 environment; it includes the five post-Soviet states of Central Asia – Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan – the Chinese province of Xinjiang, Afghanistan, adjacent regions of Iran, northern parts of Pakistan, and regions bordering India. See Dave, B. and Kobayashi, Y., ‘China’s Silk Road Economic Belt Initiative in Central Asia: Economic and Security Implications’, Asia Europe Journal, Vol. 16, 2018, pp. 267-281.

6. Myers, S.L., ‘China offers the Taliban a warm welcome while urging peace talks’, New York Times, 21 September 2021 (https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/28/world/asia/china-taliban-afghanistan.html).

7. The definition of connectivity ‘ranges widely: from strategic investment in infrastructure for geopolitical and economic purposes to initiatives aimed at deepened human-to-human interaction ...’ See: Pugliese, G., ‘The European Union’s security intervention in the Indo-Pacific: Between multilateralism and mercantile interests’, Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, September 2022, pp.1-23.

8. Russia’s ‘Greater Eurasian Partnership’ encompasses China, India, Pakistan and Iran. The Lapis Lazuli Corridor links Afghanistan with Turkey via Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan and Georgia. The 2011 Ashgabat Agreement between Afghanistan, Iran, Oman, Qatar, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan is a parallel initiative with the INSTC and the Lapis Lazuli Corridor. Currently, Kazakhstan, Pakistan and India are also members of the Ashgabat Agreement; Qatar withdrew in 2013. See Contessi, N.P., ‘In the shadow of the Belt and Road: Eurasian corridors on the North-South axis’, Reconnecting Asia, Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), 3 March 2020 (https://reconasia.csis.org/shadow-belt-and-road/).

9. The INSTC originated with the inter-governmental agreement between Russia, Iran and India which entered into force in 2002. 13 countries have since ratified it. The INSTC gained renewed impetus with the lifting of UNSC sanctions against Iran in January 2016. See ‘In the shadow of the Belt and Road: Eurasian corridors on the North-South axis’, op.cit.

10. Pantucci, R., ‘Enlisting China and Russia in managing Afghanistan’, Commentary, RUSI, 24 August 2021 (https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/enlisting-china-and-russia-managing-afghanistan).

11. The Quadrilateral Coordination Group (QCG – US, China, Pakistan and Afghanistan), the Trilateral Core Group (Afghanistan, Pakistan and the US), the Doha Process led by the Troika (China, Russia and the US), the Turkish-led Istanbul Process/Heart of Asia and the 6+2 Contact Group (including Afghanistan’s six neighbours, Russia and the US) are all examples of this.

12. Peters, S. et al., ‘Summaries of important areas for mineral investment and production opportunities of nonfuel minerals in Afghanistan’, US Geological Survey, September 2011 (https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/ofr20111204).

13. Pannier, B., ‘Northern Afghanistan and the new threat to Central Asia’, Central Asian Papers, Foreign Policy Research Institute, 13 May 2022 (https://www.fpri.org/article/2022/05/northern-afghanistan-and-the-new-threat-to-central-asia/).

14. UNODC, ‘Drug situation in Afghanistan 2021: Latest findings and emerging threats’, UNODC Research Brief, November 2021.

15. Byrd, W., ‘Taliban are collecting revenue – but how are they spending it?’, Analysis and Commentary, United States Institute of Peace (USIP), 2 February 2022 (https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/02/taliban-are-collecting-revenue-how-are-they-spending-it).

16. Kelemen, B., ‘China’s economic stabilization efforts in Afghanistan: a new party to the table?’, Policy Analysis, Middle East Institute, 21 January 2020 (https://www.mei.edu/publications/chinas-economic-stabilization-efforts-afghanistan-new-party-table#_ftn15); Lillis, J., ‘Cargo leaves China for Afghanistan on new route via Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan’, Eurasianet, 21 September 2022 (https://eurasianet.org/ cargo-leaves-china-for-afghanistan-on-new-route-via-kyrgyzstan-uzbekistan).

17. World Bank, ‘Afghanistan Overview’ (https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/afghanistan/overview).

18. FAO, ‘Afghanistan: Integrated Food Security Phase Classification Snapshot’, September 2021-March 2022 (https://www.ipcinfo.org/fileadmin/user_upload/ipcinfo/docs/IPC_Afghanistan_AcuteFoodInsec_2022MarNov_snapshot.pdf).

19. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, A/HRC/51/6: ‘Situation of Human Rights in Afghanistan – Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Afghanistan’, 9 September 2022 (https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/country-reports/ahrc516-situation-human-rights-afghanistan-report-special-rapporteur).

20. The latest reliable trade data available for Afghanistan is from 2019. World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS), ‘Afghanistan trade – Latest trade data available from various sources’ (https://wits.worldbank.org/CountrySnapshot/en/AFG).

21. ADB, ‘Afghanistan’, Key Indicators Database (https://kidb.adb.org/economies/afghanistan).

22. The EIB contributed €70 million to the funding of CASA-1000. EEAS, ‘Connecting Europe and Asia: the EU Strategy’, September 2019 (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/eu-asian_connectivity_factsheet_september_2019.pdf_final.pdf).

23. CSIS, ‘The TUTAP Interconnection Concept and CASA-1000’, 6 June 2014 (https://www.csis.org/events/tutap-interconnection-concept-and-casa-1000).

24. Uzbekistan did not sign the agreement and Turkmenistan has not ratified it. ECO Secretariat, ‘ECO transit transport framework agreement’, May 1998 (https://eco.int/parameters/eco/modules/cdk/upload/content/general_content/3758/1515303370972om85qvdt8gggqsf9ed3ss6q4e5.pdf).

25. FirstPost, ‘The long and troubled history of TAPI Pipeline: What you need to know about ambitious gas pipeline project’, 28 January 2022 (https://www.firstpost.com/world/the-long-and-troubled-history-of-tapi-pipeline-what-you-need-to-know-about-ambitious-gas-pipeline-project-10328721.html).

26. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA),‘Afghanistan Trust Fund’ (https://chfafghanistan.unocha.org/).

27. Zelin, A., ‘Turkey calls for recognition of the Taliban’s Islamic Emirate’, Policy Analysis, The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 17 March 2022 (https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/turkey-calls-recognition-talibans-islamic-emirate); Dalay, G., ‘Will Turkey’s Afghanistan ambitions backfire?’, Expert Comment, Chatham House, 6 October 2022 (https://www.chathamhouse.org/2021/10/will-turkeys-afghanistan-ambitions-backfire).

28. Current member states of the EAEU are Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Russia. See website of the Eurasian Economic Union (http://www.eaeunion.org/?lang=en#about-history).

29. Deutsche Welle, ‘Examining Indo-Iranian relations’, Interview with Michael Kugelman by Gabriel Dominguez, 5 August 2018 (https://www.dw.com/en/examining-the-implications-of-the-indo-iranian-chabahar-port-deal/a-18439937).

30. See Srivastava, D.P., ‘Changing landscape of Central Asia’, in Gupta, A. and Wadhwa, A. (eds.), India’s Foreign Policy: Surviving in a turbulent world, SAGE Publications, New Delhi, 2020, pp.281, 295.

31. Pantucci, R., ‘Inheriting the storm: Beijing’s difficult new relationship with Kabul’, The Diplomat, December 2022 (https://magazine.thediplomat.com/#/issues/-NHclFyTisdQ-cM12YNS).

32. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC, ‘Wang Yi chairs the first “Neighbouring Countries of Afghanistan plus Afghanistan” Foreign Ministers’ Dialogue’, 31 March 2022 (https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/eng/zxxx_662805/202204/t20220401_10663013.html).

33. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PRC, ‘The Tunxi Initiative of the Neighboring Countries of Afghanistan on Supporting Economic Reconstruction in and Practical Cooperation with Afghanistan’, 1 April 2022 (https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjdt_665385/2649_665393/202204/t20220401_10662024.html).

34. International Crisis Group, ‘China-Pakistan economic corridor: Opportunities and risks’, Asia Report No. 297, 29 June 2018.

35. Ibid.

36. ‘Inheriting the storm: Beijing’s difficult new relationship with Kabul’, op.cit.

37. Thorne, D. and Spevack, B., ‘Harbored ambitions: How China’s port investments are strategically reshaping the Indo-Pacific’, C4ADS, 2017, pp. 44-5.

38. See ‘China’s Silk Road Economic Belt Initiative in Central Asia: Economic and Security Implications’, op.cit..

39. Diesen, G., ‘How Russia’s Greater Eurasian Plan may spell the end of EU- centric model’, Russia in Global Affairs, 2 November 2018, quoted in Hofstee, G. and Broeders, N., ‘Multi-dimensional chess: Sino-Russian relations in Central Asia’, Clingendael, November 2020 (https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/2020-11/Strategic_Alert_Sino-Russian_relations_November_2020.pdf).

40. Köstem, S., ‘Russia’s search for a Greater Eurasia: Origins, promises, and prospects’, Kennan Cable No. 40, Wilson Center, February 2019 (https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/kennan-cable-no-40-russias-search-for-greater-eurasia-origins-promises-and-prospects).

41. Gul, A., ‘Regional nations urge US to unfreeze Afghan assets’, VOA News, 16 November 2022 (https://www.voanews.com/a/regional-nations-urge-us-to-unfreeze-afghan-assets/6837288.html).

42. Delegation of the EU to Afghanistan, ‘EU-Afghanistan Relations’, 14 August 2022 (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/eu-afghanistan-relations_en?s=234).

43. The EU is the largest global source of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), with a total stock of €11.6 trillion, compared to China’s €1.9 trillion. Borrell, J., ‘The EU needs a strategic approach for the Indo- Pacific’, EEAS, 12 March 2021 (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/eu-needs-strategic-approach-indo-pacific_en).

44. European Parliament, ‘Central Asia’, Fact Sheets on the EU (https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/178/central-asia).

45. Delegation of the EU to Uzbekistan, ‘Samarkhand EU-Central Asia Connectivity Conference: Global Gateway’, 21 October 2022 (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/delegations/uzbekistan/samarkand-eu-central-asia-connectivity-conference-global-gateway_en?s=233).

46. The EU is currently Kazakhstan’s largest trading partner and top investor. European Commission, ‘Trade – Kazakhstan: EU trade relations with Kazakhstan: Facts, figures and latest developments’ (https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/kazakhstan_en).

47. ECFR, ‘EU Energy Deals Tracker’ (https://ecfr.eu/special/energy-deals-tracker/?country=eu).

48. ‘Central Asia’, Fact Sheets on the EU, op.cit.‘

49. EU Energy Deals Tracker’, op.cit.

50. European Commission, ‘Mobility and Transport – Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T)’, (https://transport.ec.europa.eu/transport-themes/infrastructure-and-investment/trans-european-transport-network-ten-t_en).

51. European Commission, ‘Connecting Europe and Asia – Building Blocks for an EU Strategy’, Joint Communication to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, the Committee of the Regions and the European Investment Bank, 19 September 2018 (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/joint_communication_-_connecting_europe_and_asia_-_building_blocks_for_an_eu_strategy_2018-09-19.pdf)

52. ‘Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T)’, op.cit.

53. Council of the European Union, ‘Coordinated Maritime Presences: Council extends implementation in the Gulf of Guinea for two years and establishes a new Maritime Area of Interest in the North-Western Indian Ocean’, Press Release, 21 February 2022 (https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/02/21/coordinated-maritime-presences-council-extends-implementation-in-the-gulf-of-guinea-for-2-years-and-establishes-a-new-concept-in-the-north-west-indian-ocean/).