You are here

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Insight 1: Defining Europe's (collective) role in Afghanistan

- Insight 2: A misconceived centralisation policy

- Insight 3: The spectre of corruption

- Insight 4: Getting the national-international equation right

- Insight 5: The (neglected) role of Pakistan

- Past lessons, future prospects

- References

The EU engagement in Afghanistan

Introduction

Political crises have a way of bringing the assumptions, miscalculations and fallacies of the past into sharp relief. The Taliban’s capture of Kabul on 15 August 2021, and the subsequent collapse of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan in the days following the withdrawal of international troops, is no exception. Even as thousands of Afghans rushed to Kabul airport in a desperate attempt to flee the Taliban, hopes remained that the more moderate elements of the regime would prevent a return to the draconian policies that characterised the group’s first stint in power. Following the Taliban’s ban on teenage girls attending school and their introduction of over thirty edicts aimed at the systematic exclusion of Afghan women from all aspects of social, economic, and political life, these hopes have all but dissipated (1). With the decision of many donors to suspend non-humanitarian aid to Afghanistan in response to the Taliban’s repressive policies, the already dire humanitarian conditions caused by years of conflict, recurring droughts and chronic poverty have deteriorated to unprecedented levels (2). As of June 2022, 6.6 million Afghans live at emergency levels of food insecurity – the highest figure of any country in the world (3). In the wake of the 6.1-magnitude earthquake that devastated the remote south-eastern region of Afghanistan on 22 June 2022, a rising death toll, difficulties in delivering emergency aid, and a grave risk of disease have been added to the list of the country’s immense humanitarian challenges (4).

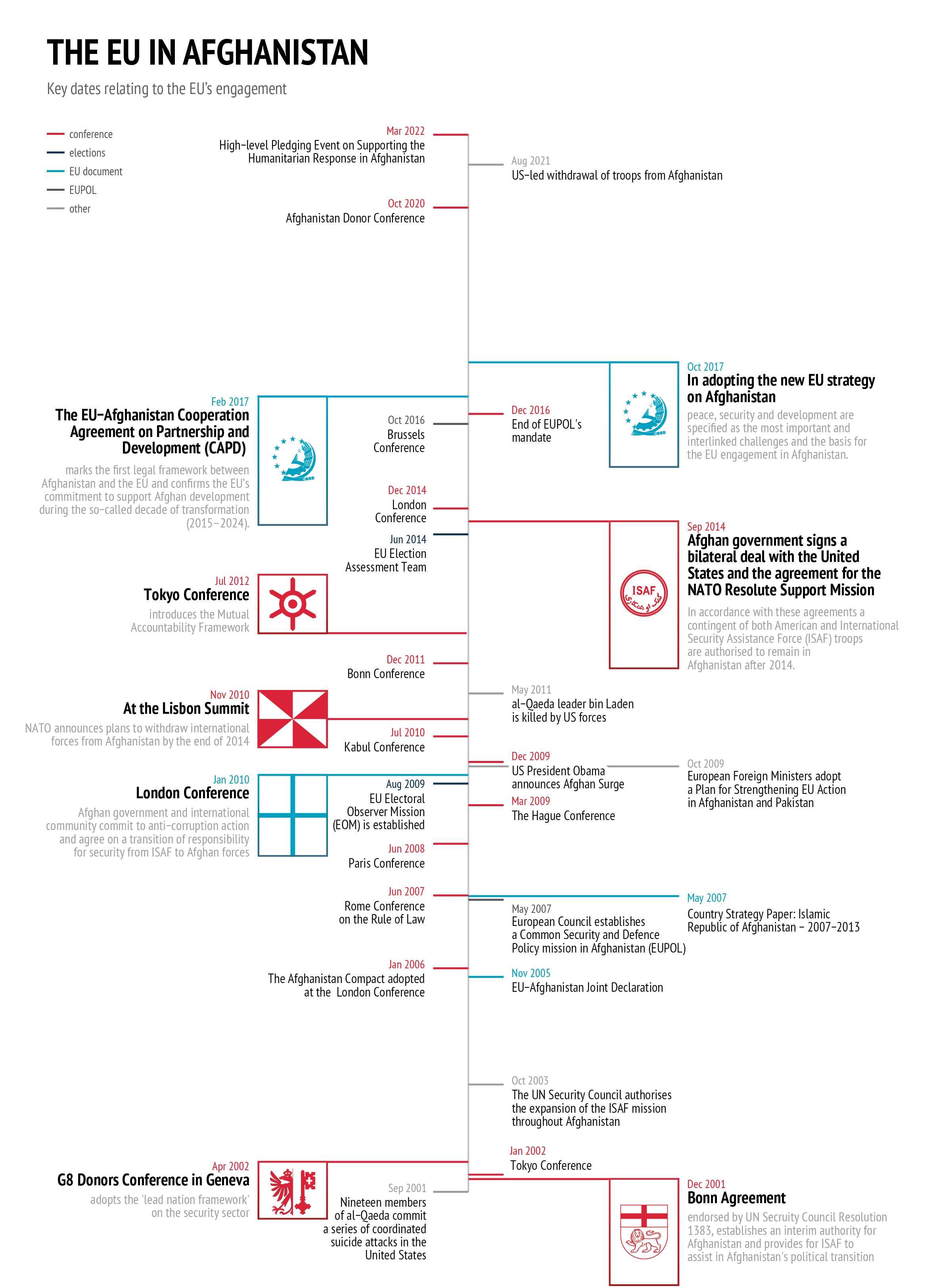

While much criticism has been levelled against European states since the chaotic international withdrawal from Afghanistan, the speed with which events have unfolded since mid-August 2021, and the gravity of the developments that have occurred, have highlighted the need for a detailed analysis of the EU’s engagement in the country over the past twenty years. While the chain of events following the US-led evacuation from Afghanistan have laid bare a range of strategic errors and miscalculations, they also offer a seminal opportunity to review and re-evaluate the EU’s approach to supporting states manage the complex transition to post-conflict stability. As a proliferating number of expert analyses suggests, any such evaluation must build on the recognition that there is no simple explanation, no clear-cut set of factors or events, that can solely account for the developments leading up to the Taliban’s seizure of power. On the contrary, the myriad complexities of the Afghan context, alongside the number and diversity of actors with a stake in the country’s conflict, caution against the impulse to draw swift or definitive conclusions. With a view to these considerations, this Brief does not aim to provide an exhaustive overview of the events and developments that have shaped the EU’s role in Afghanistan since the overthrow of the Taliban in 2001 (5). Instead, it draws on roundtable consultations with senior Afghan and EU policy practitioners to identify five key insights from the EU’s engagement in Afghanistan over the past twenty years (6). In the final section of the Brief, considerations for the EU’s present and future engagement in Afghanistan are outlined.

Insight 1: Defining Europe's (collective) role in Afghanistan

Two key factors can be identified as having shaped the EU’s positioning within the broader international engagement in Afghanistan. Following the terrorist attacks of 9/11 and the first ever invocation of Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty, European engagement in Afghanistan was characterised by a willingness to adapt to US-determined priorities and strategies. Informed by a profound sense of solidarity with the United States, efforts to establish a distinctive European position were hampered by a reluctance, prevalent among European states, to challenge or openly deviate from a US-set agenda. Accordingly, while the EU presence was viewed positively by many Afghans – and the EU provided a significant proportion of the budget underpinning the development, democracy assistance, and state-building efforts - the EU’s ability to exert political or diplomatic influence commensurate with this contribution remained limited (7). While the EU sought to set itself apart from the United States in prioritising an inclusive inter-Afghan dialogue over the US-Taliban peace process, the broad European acquiescence to US strategic leadership constrained the EU’s political influence (8).

Data: European Commission, GISCO, 2022; Natural Earth, 2022; OpenStreetMap, 2022

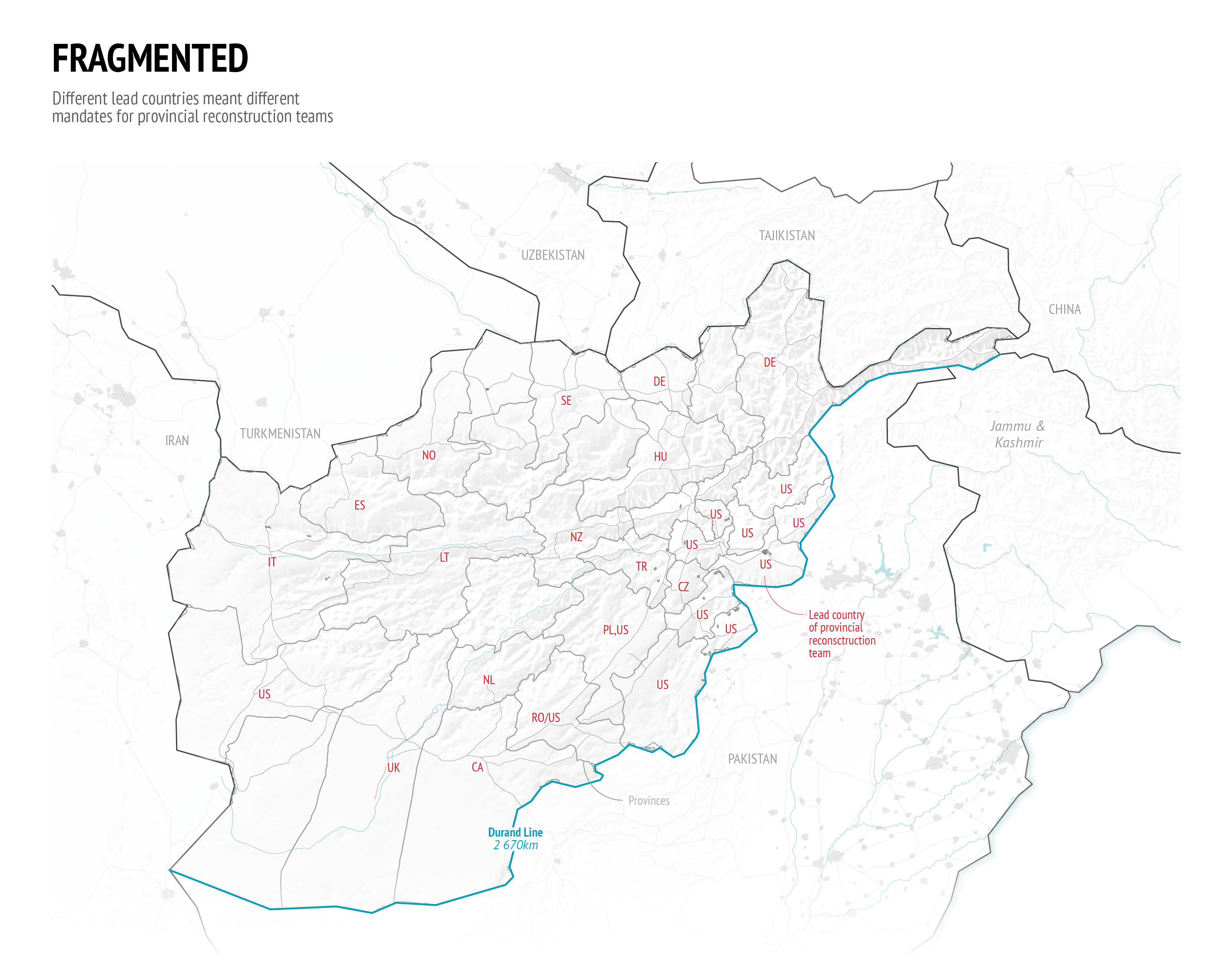

While successive EU strategies over the course of its twenty-year engagement demonstrate determination on the European side to meet the expectation for greater EU leadership expressed by both Afghan and US representatives (9), its ability to deliver on this ambition was limited by a lack of internal coherence among EU Member States. Beginning with the 2002 lead nation framework, which afforded lead responsibility for specific assistance areas to individual states, European Member States frequently pursued operationally distinct mandates in Afghanistan. The ensuing bifurcation of activities and competencies was further entrenched under the Provincial Reconstruction Team model, which saw key Member States focus attention and resources on operationally separate assistance efforts. While EU foreign ministers adopted a plan to strengthen the EU’s engagement in Afghanistan in 2009, this ‘proliferation of national approaches’ (10) meant that the EU delegation was largely reliant on Member States and international partners for local intelligence, expertise and networks. According to a senior EU official present at the time, this resulted in an outsourcing of the EU funds and mandates to Member State-led programmes, with the result that the expectation for more assertive EU leadership remained unmet.

The centralised model was largely at odds with the cultural and ethnic heterogeneity of Afghan society.

While these dynamics reportedly contributed to the EU’s limited influence over key strategic decisions made by the United States during the final years of the international engagement, several senior policy officials noted that EU Member States expressed tacit relief at the prospect of a US-determined evacuation from Afghanistan. In this way, it was noted that the operational and strategic predominance of the United States granted its increasingly ‘war fatigued’ EU and NATO allies an opportunity to exit what in the words of one commentator constituted an ‘unwinnable engagement’.

Insight 2: A misconceived centralisation policy

The decision to model the post-2001 Afghan government on a highly centralised presidential democracy had important repercussions for the trajectory of the internationally backed state and democracy-building efforts. By vesting pre-eminent political power in the presidency, the Bonn Agreement of 2001 and the Afghan constitution of 2004 disregarded a longstanding tradition that granted Afghanistan’s diverse provinces a significant degree of administrative and political autonomy. Moreover, the centralised model was largely at odds with the cultural and ethnic heterogeneity of Afghan society: Pashtuns represent some 42 % of the Afghan population; Tajiks roughly 27%; Uzbeks constitute 15 %, while other ethnic groups make up the remaining 16%. In their pursuit of a Weberian state model, European states and their international partners channelled far higher levels of funding to centralised state-building and democracy efforts than to the political empowerment of Afghanistan’s vast and impoverished rural areas. Although Western officials noted that local governance would be pivotal to the effort of ‘consolidating a stable, legitimate state’ (11), and the EU extended its support to numerous local development programmes, local democracy assistance was undermined by a strong preference for centralisation that the EU and its partners deemed a necessary precondition to the broader goals of stabilisation and development.

European Member States frequently pursued operationally distinct mandates in Afghanistan.

With over 70 % of the Afghan population residing in rural areas, the growing divide between Afghanistan’s rural and urban populations was reinforced by the resistance of the Kabul-based government to devolve power and resources away from the centre. Contrary to the widely held assumption that the central government had aimed, but failed,to extend the reaches of the Afghan Republic to the country’s rural and remote districts, expert reports have found that the Afghan leadership deliberately pursued a policy of power retention and personal enrichment that resulted in a systematic disregard for the country’s impoverished, eastern and western fringes(12). If, as the US Government Counterinsurgency Guide suggests, ‘[t]he perceived capacity of local government to provide for the population is critical to national government legitimacy’ (13), this policy may be identified as a critical impediment to the state-building and democratisation objectives pursued by the EU and its international partners.

Data: Carnegie Europe, 2021

Insight 3: The spectre of corruption

As early as 2009 a US Agency for National Development (USAID) report showed that ‘pervasive, entrenched, and systematic corruption’ had reached ‘unprecedented levels in the country’s history’ (14). Notwithstanding such findings, the success of both Afghan and international efforts in curbing the widespread and systemic corruption that plagued the country remained strikingly limited (15). A series of interlinked factors contributed to this outcome. First, the US-led security, stabilisation and counterterrorism agendas tended to overshadow the state-building and democracy assistance efforts pursued by the EU and its international partners (16). As noted by a senior expert, this was borne out by an approach that understood security as a prerequisite to good governance and accountability (17). Rather than recognising that frustration and disillusionment caused by acute and systematic corruption constituted ‘a force multiplier’ for an expanding insurgency (18), detailed studies have found that the US-led stabilisation strategy was built on the assumption that questions of security needed to be settled before governance concerns could be addressed (19).

Rather than a by- product of weak statehood, corruption was the centrepiece of a ‘vertically integrated’ system of enrichment.

As Sarah Chayes, former consultant on corruption to the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) and the US Joint Chief of Staff, has found, this operational logic was further compounded by the tendency to portray Afghan corruption as a top-down system of patronage (20). Challenging this widely held assumption, Chayes has contended that under the centralised presidential system established in 2001, corrupt activity flowed from the bottom up rather than the top down as progressive layers of subordinate officials paid off their superiors for privileges and immunity (21). Rather than a by-product of weak statehood, corruption was the centrepiece of a ‘vertically integrated’ (22) system of enrichment (23). In the absence of a rigorously enforced system of accountability, the pledging of ever-greater aid contributions, alongside the immense pressure on EU officials to spend development budgets within designated timeframes, inadvertently reinforced a state-run system of corruption. In so doing, the failure to tackle rampant corruption among Afghanistan’s new political elite not only undermined trust in the fledgling Afghan Republic but drove many disenchanted Afghans into the arms of the Taliban insurgency.

Insight 4: Getting the national-international equation right

The tension between Afghan ownership and the internationally determined timelines and objectives entailed serious consequences for the prospects of consolidated statehood and democracy in Afghanistan. This became manifest with the decision to transition authority over the electoral process to Afghan institutions in 2009. While the first post-Taliban elections in 2004 and 2005 were celebrated as a remarkable logistical success, a strict adherence to notions of national ownership rather than a nuanced analysis of circumstances on the ground is reported to have informed the international determination to transfer responsibility for the 2009 elections to Afghan control. Specifically, while the EU’s Electoral Observer Mission (EOM) had identified serious irregularities during the 2005 electoral process, evidence of pervasive ballot stuffing, intimidation and fraud did not give rise to action at the political level (24). Given the electoral system’s evident vulnerability, the international insistence on an operationally abstract timeline was found to have played an important role in enabling the widespread and systemic fraud that characterised the 2009 Presidential and Provincial Council elections. Moreover, the international failure to deliver a concerted response to such malpractice significantly damaged the perceived credibility of Afghanistan’s nascent democracy, setting in motion a process whereby each subsequent election further discredited, rather than bolstered Afghanistan’s ostensibly representative institutions.

The premature transition to Afghan ownership in the political realm stands in notable contrast to the international reluctance to facilitate a broader transition to Afghan authority in the military realm. While the NATO-led Inteqal or ‘Transition’ process foresaw that the 2014 NATO drawdown would be accompanied by a simultaneous transfer of the military strategy to Afghan control, the eleventh-hour agreement that a contingent of 9 800 American and at least 2 000 NATO troops would remain in Afghanistan after 2014 (25) effectively forestalled this process. Specifically, while the strategy had envisioned a transfer of command to Afghan hands and a corresponding surge in Afghan capacity, authority and responsibility, the continued leadership of American and NATO troops meant that a substantive transition of military authority did not take place until the weeks immediately prior to the international withdrawal in 2021. Viewing these developments retrospectively, it has been argued that, however well intentioned, the internationally determined timeline for the transition to Afghan ownership proved to be of unexpected detriment to the country’s democratic and military prospects.

Insight 5: The (neglected) role of Pakistan

The role and significance of Afghanistan’s immediate geographic and political neighbourhood was not granted sufficient attention by the EU and its international partners. In particular, the influence of Pakistan in shaping the prospects and trajectory of Afghanistan’s stabilisation was widely underestimated. The unresolved question of the Durand Line – the 2 670-kilometre Afghan-Pakistani border – and Afghanistan’s persistent claim to the contiguous Pakistani Pashtun majority areas significantly strained the Afghan government’s relationship with its immediate western neighbour (26). Premised on Islamabad’s dual objectives of curbing Pashtun nationalism and ensuring the installation of a pro-Pakistani government in Kabul, Pakistan pursued an active, if not uncomplicated, policy of support for the Afghani Taliban (27).

Pakistan pursued an active, if not uncomplicated, policy of support for the Afghani Taliban.

Given its defining role in providing the Afghan insurgency with a space to retreat and recuperate, alongside the progressively more fluid movement of Pakistani and Afghani Taliban across the Durand Line, a resolution of the Afghan conflict depended upon a close consideration of Pakistan’s goals and political objectives. Crucially, these needed to address Pakistan’s fraught relationship with India and the broader web of regional politics in which the Afghan conflict continues to be embedded. While EU foreign ministers signalled their acknowledgement of Pakistan’s combined geographic and strategic significance with the 2009 adoption of a plan for ‘Strengthening EU Action in Afghanistan and Pakistan’, it has been argued that European policymakers fell short of providing the Pakistani leadership with the political incentives necessary to ensure a decisive shift in Islamabad’s policy towards the federally administered tribal areas (FATA) on its Afghan frontier (28). Moreover, while senior members of the EU delegation sought to draw on the European example of regional cooperation, strained relations with both Iran and Pakistan meant that these efforts did not translate into concrete results. Given Islamabad’s repeated efforts to position itself as a peacemaker (notably exemplified by its involvement in setting up the Quadrilateral Coordination Group (QCG) in 2016), the full importance of Pakistan as a major stakeholder in the region did not garner the attention or the concerted political consideration it warranted.

Past lessons, future prospects

Given that the collapse of the international state-building efforts in Afghanistan risks dissuading European states from committing to future efforts to support the rebuilding of conflict-afflicted states, the Taliban’s resumption of power, while clearly a political debacle, also presents a critical opportunity: one for a clear-eyed review and re-evaluation of the EU’s approaches and priorities. Apart from the revelation of strategic miscalculations, the events of August 2021 demonstrate that it is imperative to ensure that the lessons from the EU’s past engagement inform and ameliorate its policies in the present and the future. With a view to contributing to this endeavour, the following policy considerations may be identified.

Attention to context and the need to challenge prevailing assumptions

It is essential for international actors to understand the cultural, historical and political context of the territories in which they engage, as a premise to developing common strategic responses. Rigorous, detailed and continued political analysis is needed to adapt international responses to the shifting realities on the ground. To this end, international actors must prioritise information systems that are designed to identify and challenge prevailing assumptions and capture negative signals. To render these systems effective, the EU should consider introducing varied policy reviews at regular, operationally meaningful intervals.

Understanding the inclusivity- security nexus

There are no security solutions for fundamentally political problems. Notwithstanding this truism, when groups or individuals are barred from achieving their objectives through political means, it risks incentivising violence as a means of pursuing change. On these grounds, efforts to establish security and curb violence must be premised on a willingness to understand the demands of the full range of legitimate constituencies. Detailed attention to who those constituencies are and where to draw the line between engagement and endorsement must be understood as a diplomatic and political priority.

Strengthening the link between state- and nation-building

While much focus has been placed on (re-) building the capacity and institutions of conflict afflicted-states, greater emphasis must be placed on strengthening the relationship between post-conflict states and their societies. Specifically, international engagements must prioritise supporting both the capability and the accountability of state institutions, as a basis for citizens’ confidence, trust and support of new governance structures. While international support plays an important role, the ability to overcome conflict and achieve stability will hinge on the establishment of a functioning social contract.

Prioritising preventative action

Post-conflict states face a high risk of conflict relapse. Anticipating, identifying and forecasting potential conflict triggers can significantly lower the risk of future conflict, while contributing to the prospects of sustainable peace and development. International actors must combine strategic foresight with a preparedness for rapid action to avoid the perpetuation of conflict cycles. This will require improved intelligence cooperation and interoperability; looking beyond quick-fix solutions to address the root causes of state fragility; and, last but not least, investment in strengthening local capacities.

References

1. United Nations Meeting Coverage and Press Releases, ‘Amid plummeting humanitarian conditions in Afghanistan, women, girls “are being written out of society” by de facto authorities, briefers warn Security Council’, 23 June 2022 (https://www.un.org/press/en/2022/sc14946. doc.htm); Ahmadi, B., and Tariq, M. O., ‘How the Taliban’s hijab decree defies Islam: The worst-case scenario for Afghan women is playing out before our eyes. The international community cannot sit by idly’, United States Institute of Peace, 12 May 2022 (https://www.usip.org/ publications/2022/05/how-talibans-hijab-decree-defies-islam).

2. UNHCR Regional Bureau for Asia and Pacific, ‘External Update: Afghanistan Situation #17’, 1 June 2022 (file:///Users/fee/ Downloads/2022.06.01%20EXTERNAL%20AFG%20Situation%20 Emergency%20Update%20(1).pdf); UN News, ‘World can end downward spiral of Afghanistan’, 31 March 2022 (https://news.un.org/en/ story/2022/03/1115102).

3. ‘Amid plummeting humanitarian conditions in Afghanistan, women, girls “are being written out of society” by de facto authorities, briefers warn Security Council’, op.cit.

4. UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, ‘Afghanistan: Flash Update #4: Earthquake in Paktika and Khost Provinces, Afghanistan’, 26 June 2022 (https://reliefweb.int/report/afghanistan/ afghanistan-flash-update-4-earthquake-paktika-and-khost- provinces-afghanistan-26-june-2022).

5. A publication of this brevity cannot illuminate more than a handful of themes that are selected from among many others that warrant careful consideration by policymakers and practitioners. For instance, this Brief does not delve into critical developments such as the Afghan Peace Process, the US Counterterrorism Strategy, or the Taliban’s role in Afghanistan since 2021. Instead, it is narrowly focused on a set of defining trends and factors related to the EU’s engagement in Afghanistan that were identified by senior Afghan and EU policymakers during roundtable discussions held in 2021-2022.

6. The European External Action Service (EEAS) has instigated an assessment of the EU’s engagement in Afghanistan over the last twenty years. To inform and facilitate this broader evaluation process, the EUISS in cooperation with the EEAS hosted a succession of three roundtable discussions that brought together senior Afghan and EU policy practitioners, experts, and journalists, as well as representatives from the United Nations, NATO, and non-governmental organisations.These roundtable seminars were held under the Chatham House Rule on 9 December 2021, 3 February 2022, and 16 March 2022, respectively.

7. Burke, E., ‘Game over? The EU’s legacy in Afghanistan’, FRIDE, Working Paper No 122, February 2014.

8. European Union External Action Service, ‘Statement by the Spokesperson on the outcome of the Intra-Afghan Dialogue in Doha’, 9 July 2019 (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/node/65164_en).

9. Keohane, D., ‘ESDP and NATO’, in Grevi, G., Helly, D., and Keohane, D. (eds.), European Security and Defence Policy: The first 10 years (1999-2009), EUISS, Paris, 2009.

10. Perito, M. R., ‘The U.S. experience with Provincial Reconstruction Teams in Afghanistan: Lessons identified’, United States Institute of Peace, 1 October 2005 (https://www.usip.org/publications/2005/10/us-experience-provincial-reconstruction-teams-afghanistan-lessons-identified).

11. Brown, F. Z., ‘Aiding Afghanistan’s local governance: What went wrong?’, Carnegie Endowment of International Peace, 8 November 2021 (https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/11/08/aiding-afghan-local- governance-what-went-wrong-pub-85719).

12. See: Chayes, S., Thieves of State: Why corruption threatens global security, W.W. Norton & Company, London, 2015.

13. United States Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, ‘U.S. Government Counterinsurgency Guide’, January 2009, p. 30 (https://2009-2017.state. gov/documents/organization/119629.pdf).

14. USAID, ‘Assessment of corruption in Afghanistan’, Washington D.C., 2009, p.1.

15. ‘Game over? The EU’s legacy in Afghanistan’, op.cit., p.2.

16. Remarks made by Kate Bateman, of the US Institute of Peace, during a conference entitled ‘Conflict in Afghanistan: A new regional security map and state-building implications since the Taliban takeover’, 11 May 2022, IISS, Washington D.C.

17. Thieves of State, op.cit., p.44.

18. Ibid., p. 43.

19. Ibid., p. 43.

20. For examples of this analysis of corruption in Afghanistan see: Rubin, R., Afghanistan from the Cold War through the War on Terror, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2013, p.177 and p.299; Rosenfeld, J., ‘US Envoy: Candidates’ support of “National Unity” is key to next Afghan government’, Asia Society, 10 July 2015 (https://asiasociety.org/blog/ asia/us-envoy-candidates-support-national-unity-key-next-afghan- government).

21. Thieves of State, op.cit.

22. Ibid., p. 62.

23. Ibid., p. 60.

24. ‘Game over? The EU’s legacy in Afghanistan’, op.cit., p. 7.

25. North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, ‘Resolute Support Mission (RSM): Key Facts and Figures’ (https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/ pdf/2021/2/pdf/2021-02-RSM-Placemat.pdf).

26. International Crisis Group, ‘Pakistan’s hard choices in Afghanistan’, Asia Report No 320, 4 February 2022 (https://d2071andvip0wj.cloudfront. net/320-pakistan-hard-policy-choices--afghanistan.pdf).

27. Mir, A., ‘Pakistan’s twin Taliban problem: Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan attacks lead to growing tension between the Afghan Taliban and Pakistan. What’s at stake?’, United States Institute of Peace, 4 May 2022 (https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/05/pakistans-twin-taliban- problem).

28. EU Council, ‘Strengthening EU Action in Afghanistan and Pakistan’, 27 October 2009 (https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ IP_09_1592).