You are here

Taliban in or out?

Introduction

The Taliban’s takeover of Kabul in the summer of 2021 seemed predictable in hindsight. Analysts and pundits alike, among them the former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, have since cast the Taliban’s resumption of power as a historic inevitability (1). The analytic shorthand that appears to underpin such assessments surmises that Afghans are too tribal and conservative to accept democracy and equality, that state structures are endemically corrupt, and that the country is too mountainous and large to be successfully secured by a foreign force. If this set of assumptions holds true, we already know what is next – the Taliban are here to stay. Except that assumptions are just that: untested beliefs. In this Brief, we strive to move beyond untested assumptions to ascertain what range of futures is possible for Afghanistan in the next five years, and why. We begin by identifying the seven critical uncertainties that are likely to define Afghanistan’s future trajectory. In the second section, we outline a scenario that pinpoints the factors that threaten the Taliban’s hold on power, while the third section specifies the conditions that would allow the Taliban to consolidate their regime. We conclude with reflections on what these findings mean for the European Union.

Afghan uncertainties

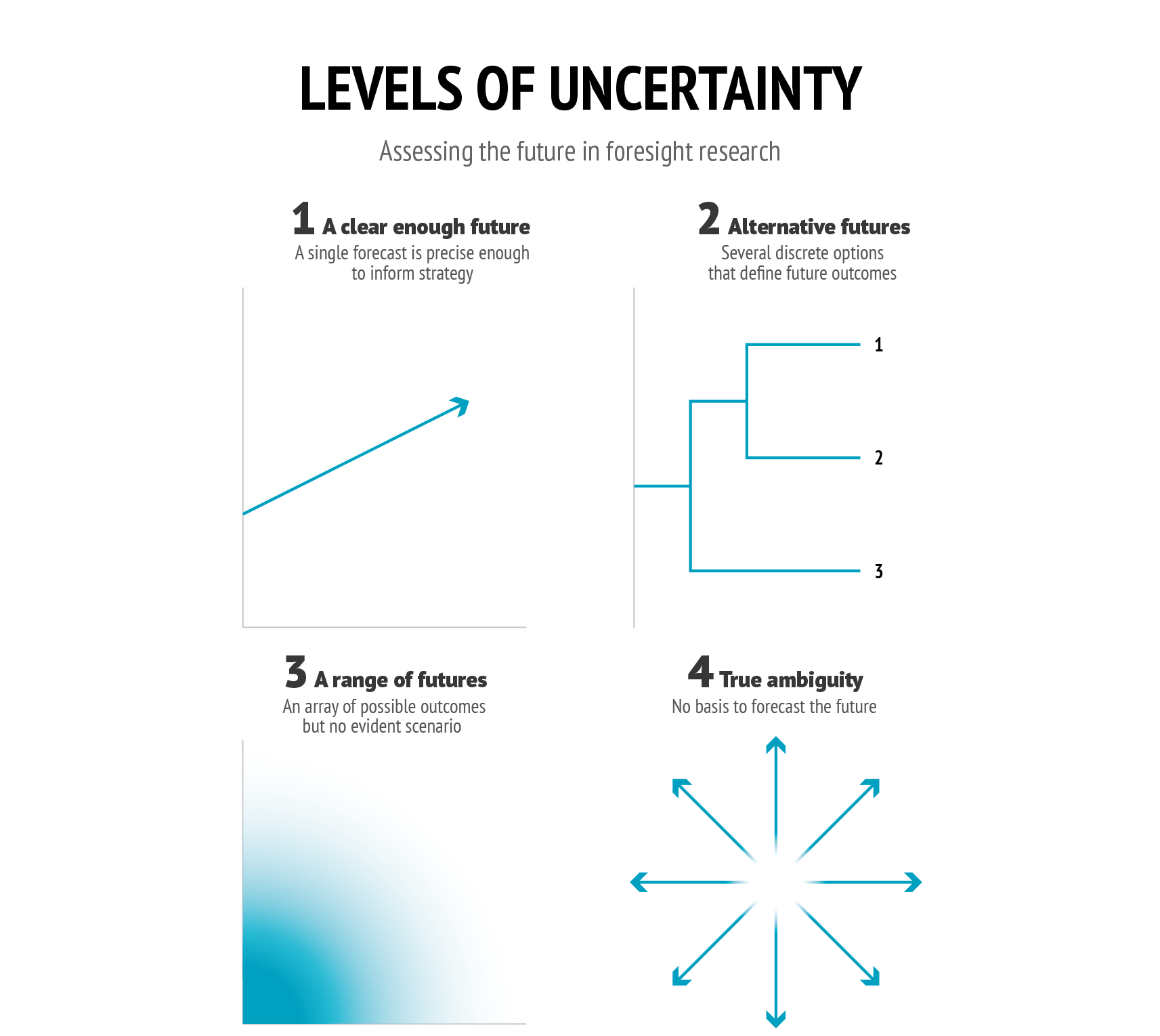

Although the condition of uncertainty is often confused with notions of threat or risk, the term effectively refers to a state of not knowing for sure. The future is by definition uncertain in myriad ways - either because we lack data and the right models, or because we are confronted with actors whose choices are not easily identified. That said, not all uncertainties are created equal: while we can have simple levels of uncertainty, matters become increasingly tricky the more choices exist, and the more actors that are involved.

Data: Harvard Business Review, 1997

The goal of foresight is to reduce such uncertainty. However, not every foresight tool will work at every level of uncertainty. Broadly speaking, we have four levels of uncertainty (2): Level 1 is characterised by the availability of data and the comparative straightforwardness of the question at hand (for instance, forecasts concerning demographics are usually based on a Level 1 uncertainty). A Level 2 uncertainty is more complex in that it proposes two or more discrete options that each entail distinct future outcomes. While several different futures are thus conceivable at this level of uncertainty, the range of possible outcomes remains clearly defined. This stands in contrast to Level 3 where there are too many choices and actors, often interlinked, to predict the range of possible outcomes. Lastly, a Level 4 of uncertainty describes a state of affairs that is quite simply too complex or ambiguous to allow for forecasting. In this Brief, we assign Afghanistan’s political future a Level 3 of uncertainty. In so doing, we identify seven factors of critical uncertainty concerning the Taliban’s ability to consolidate its grip on power over the next five years.

The threat of post-conflict relapse

As a post-conflict state, Afghanistan has a 51 % chance of relapsing into violence within the next five years (3). This is because structurally speaking, nowhere is conflict likelier to occur than in states that have just emerged from an armed conflict (4). With its repeated cycles of conflict since the 1970s, the workings of this ‘conflict trap’ are clearly exemplified in Afghanistan (5). In the aftermath of their power grab in August 2021, violent resistance against the Taliban regime is likely to emanate from three key sources: first, the National Resistance Front of Afghanistan led by Ahmed Massoud and Amrullah Saleh (comprising approximately 8 000 fighters today) has committed to a campaign of violent resistance against the Taliban from the spring of 2022 onwards. Second, the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP) (estimated to comprise anywhere between 500 and 2 000 fighters) has reportedly staged 18 attacks since the Taliban takeover (6) and will, in all likelihood, persist with their insurgency despite the relative quiet seen in recent weeks. Finally, new and/or previously unknown groups are already emerging as former police and military personnel remain unemployed, feeding into the pool of possible resistance fighters. The threat of a violent insurgency emanating from these three sources is compounded by Afghanistan’s complex geology and mountainous terrain which offer vast areas of potential hideouts and curtail the Taliban’s ability to clamp down on their opponents (7).

The uncertain means of war

War is also more likely where non-state actors can easily generate funds through the sale of raw materials such as drugs, diamonds, or timber (8). At present, 85 % of the world’s opium supply comes from Afghanistan, and a third of the country’s villages are involved in opium production (9). Climate change is expected to increase such production still further. This is because poppy is a plant that requires far less water than many subsistence crops, making it attractive to farmers faced with Afghanistan’s frequent droughts (10). While this is worrying enough, there is more bad news: because the global heroin market is saturated, there are now signs that Afghanistan’s narcotics production is shifting towards the production of synthetic drugs, such as methamphetamines (also known as crystal meth) (11). Since 2018, the production of these drugs in Afghanistan has increased almost tenfold, mirroring a global trend that also concerns Europe (12).

The threat of a violent insurgency is compounded by Afghanistan's complex geology and mountainous terrain.

The poverty-conflict nexus

These dynamics are intensified by the fact that the risk of conflict relapse is highest in states with low levels of income (13). Afghanistan is the least developed country in Asia and ranks 169 out of 189 countries on the UN’s Human Development Index (14). With the suspension of non-humanitarian aid to Afghanistan by the EU and other donors critical of the Taliban and its seizure of power, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) estimates that 97 % of Afghanistan’s population could sink below the international poverty line by mid-2022 (15). Unfortunately, climate change is poised to make this volatile economic situation still worse: 80 % of Afghans depend on agriculture, a sector that is likely to be hit hard by both droughts and floods, for their livelihood (16). The frequency of such events is projected to rise so sharply that Afghanistan ranks as the fifth most vulnerable country in the world when it comes to the risk of natural disasters. Projections suggest that droughts, combined with rapid spring snowmelt, will see land degradation and a significant loss of vegetative cover, leading to devasting consequences for livestock herders and dryland farmers (17).

The stability factor

Afghanistan has the means necessary to break out of this vicious circle of poverty and conflict. However, doing so would require that its political leadership ensures domestic stability for approximately two decades: that is the time it would take to build up the infrastructure necessary to exploit Afghanistan’s extensive lithium reserves (18). Lithium is a highly reactive rare earth element (REE) that constitutes an essential component in rechargeable batteries and other technologies vital to the global energy transition. As a result, global demand for REEs is expected to increase by 756 % by 2030 (19), leading some experts to refer to the element as ‘the new oil’ (20).

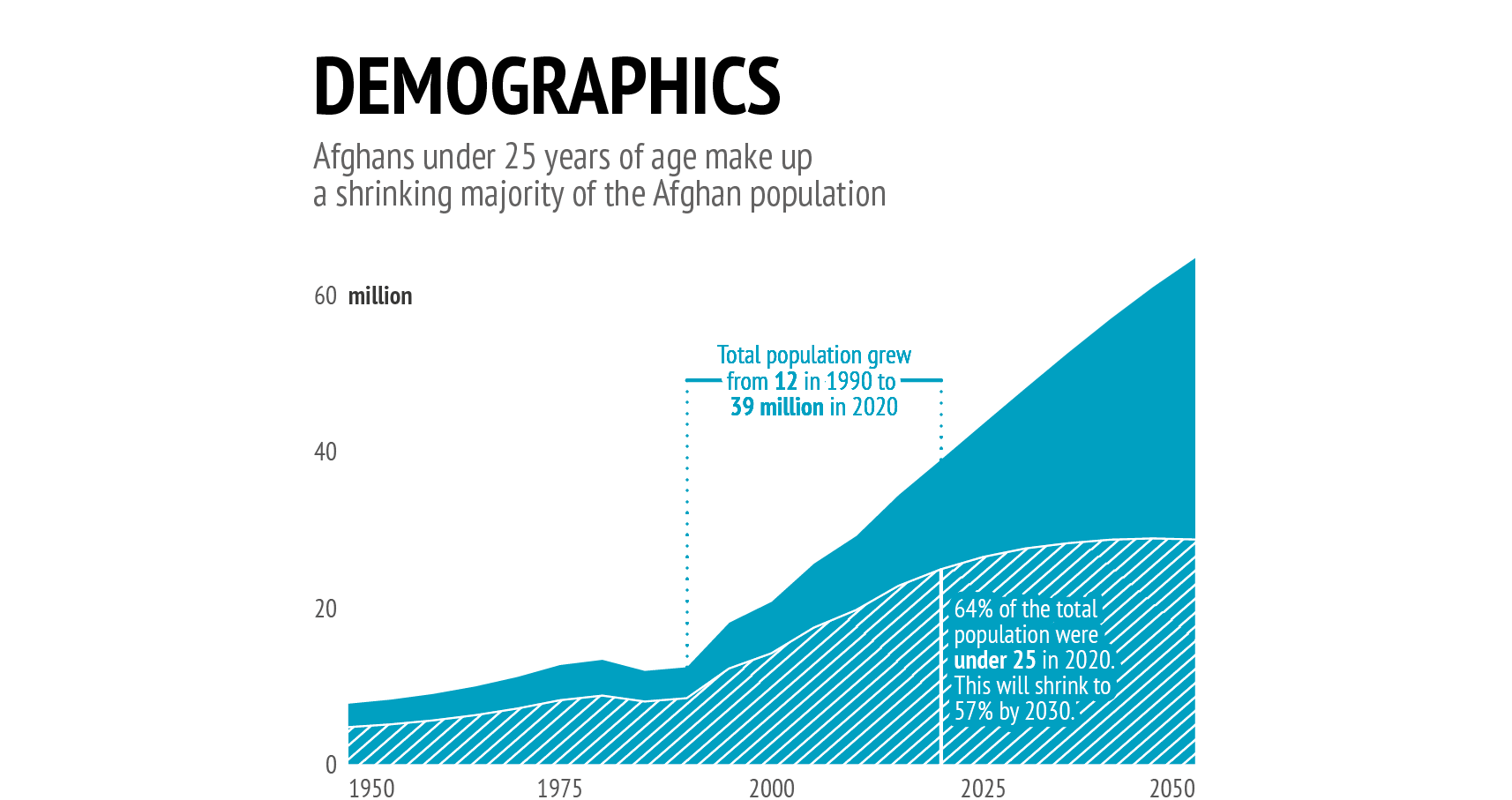

Data: UN DESA, 2022

China, the global leader in the supply of processed lithium, has already gained access to mining leases in Afghanistan (although instability, corruption and a lack of infrastructure meant that their exploitation remained limited under Afghanistan’s previous governments) and became one of the first countries to signal its willingness to play a ‘constructive role’ in Afghanistan’s economic development following the Taliban takeover in August 2021 (21). Combined with its mining ventures in other conflict-prone contexts, these factors would suggest that with a viable level of stability in place Beijing may well be inclined to consider making the investments necessary to pursue the exploitation of Afghanistan’s mineral and rare earth deposits (22).

Achieving domestic acquiescence

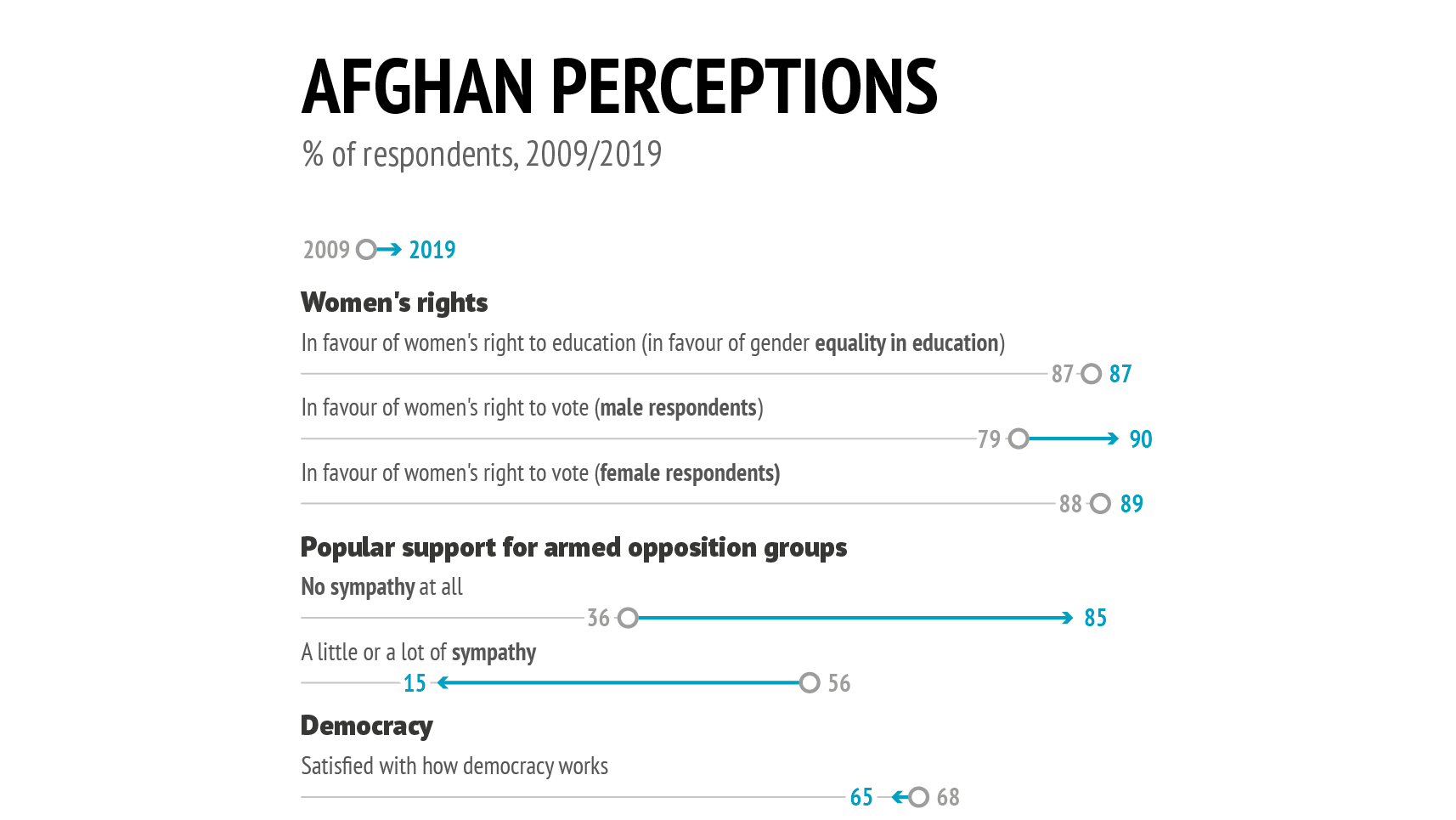

Uncertainty also derives from the fact that popular support for the Taliban has fallen markedly over the last 15 years. This shift in sentiment can be traced to the fact that, in contrast to 1996, the Taliban are no longer seen as bringing order to a divided and conflict-torn Afghanistan: today they are deemed responsible for the ambient chaos and volatility. In the three years before the fall of Kabul, between 8 800 and 10 000 civilians were killed or injured per year. The Taliban was the chief culprit of this violence, incurring more victims than any other conflict party (23). In addition, Afghan support for democracy and women’s rights has increased consistently over time (24). It is also not clear whether the Taliban leadership, which comprises many of the same figures present during its 1990s-era rule, will be able to connect to a much larger and younger constituency. The Afghan population has more than doubled since 1996 and is projected to continue to grow to 43 million by 2025 (25). Two-thirds of the population have no recollection of the Taliban’s first stint in power.

UNDP estimates that 97 % of Afghanistan's population could sink below the international poverty line by mid-2022.

The question of regime cohesion

While the Taliban’s internal cohesion will be critical for regime consolidation, the realities of governance – as opposed to insurgency – will put the group’s unity to the test. Divisions run along several lines: those factions willing to make power-sharing concessions versus the hardliners, Pashto versus non-Pashto, and the younger versus the older (26). The challenges of governing under the present circumstances are manifold too: Afghanistan has lost 75 % of its budget as this came from foreign donors, and assets abroad are still frozen (27). Even if internal tensions do not see the group’s unity crumble, they will, at a minimum, complicate the mammoth task of governing the faltering Afghan state – thereby further eroding the Taliban’s domestic legitimacy and bolstering the claims of their contenders.

Precarious international support

Lastly, Taliban rule will ultimately depend on the support the group is able to garner from international partners, especially Pakistan and Iran. Iran has expressed disquiet about ISKP attacks on Afghanistan’s Shia minority and a potential Salafi-Jihadi insurgency, prompting the mediation of talks between the Taliban and their opponents by Iran and Pakistan. Both are expected to exercise a mediating influence on the regime which could, in turn, create a degree of stability and therefore foster investments - for instance, from China. So far, China is concerned with extremist groups training in Afghanistan and targeting its workers and missions in Pakistan – as has happened repeatedly in recent years. Reducing this threat would open the door to stronger relations with Beijing. While Russia has a similar concern over extremist groups in the North Caucasus, it is unlikely to emerge as a valuable partner to Kabul anytime soon due to its own isolation and current focus on its war against Ukraine.

The sum of these factors of critical uncertainty means that we find ourselves at a juncture where there are no obvious future outcomes. Under these conditions, scenarios are useful tools to understand the interlinkages of the different strands of uncertainty, to identify possible knock-on effects, and to guide policy decisions. While considerations of time and space lead us to propose two scenarios, this should not be mistaken for a binary choice of future possibilities. Scenarios serve not to predict the future but to highlight interdependencies and the possible consequences of critical choices. Accordingly, the two scenarios outlined below seek to enhance policymaking by identifying the extreme poles of future possibility. In reality, we expect the critical uncertainties outlined in the preceding analysis to lead to a more nuanced outcome than either scenario would suggest. In articulating these scenarios, we ask: what conditions would allow the Taliban regime to persist over the next five years, and which conditions would see them lose their hold on power? We assign probabilities based on recent trends that specify the presumed likelihood of each scenario unfolding (28). Notably, these stand as a reflection of our qualitative assessment rather than the result of mathematical calculations.

Scenario: Civil war, reloaded

Probability: 70%

In this scenario, the Taliban pursue a coercive and intransigent strategy, whereby they make no concessions on the ideological front. While such an approach would ensure the Taliban’s internal cohesion, it comes with several challenges, foremost among them security: if they prove unable to deliver public order and manage conflict, the Taliban will find it impossible to stabilise the economy and forge critically important relations with their geostrategic partners. Because the Taliban are likely to face popular resistance given their ideological extremism, they will have to resort to a massive expansion of their security apparatus in order to manage security. Such an approach would entail a number of challenges: in terms of the required manpower, territorial control is far more intense than territorial conquest. While the Taliban are presumed to have 75 000 fighters today, they would have to expand their forces to approximately 195 000 fighters to reach the numbers that are conventionally quoted as being sufficient to secure a country with a population of the size of Afghanistan’s (29). Such an expansion of their armed forces would require the Taliban to integrate former police and military staff, while taking a significant toll on the budget which has just been slashed by 50 % (30). Here, the question of ideology would loom large once more as it would require the Taliban to accept the return of officers that have worked for the previous government and thus actively fought to suppress the Taliban until its power-grab in August 2021. Although it can be assumed that at this stage of Afghanistan’s steadily deteriorating humanitarian crisis income will matter more than values for the bulk of officers and troops, the question of convictions remains an obstacle as it undermines not just staffing, but cohesion more broadly. Moreover, an enlargement of the Taliban’s security apparatus only actually emerges as an option if the Taliban are able to achieve rapid access to financial backing. This is because the regime lacks viable alternatives when it comes to procuring income: with the international market for opium saturated, an increase in the cultivation and production of poppy, one of the Taliban’s principal sources of revenue over the past two decades, would not translate into a sharp increase in their income (31). As Afghanistan lacks both the mining and the transportation infrastructure necessary to turn its vast natural resources into economic boons, critical minerals such as lithium or copper will not emerge as a source of income in the near future either (32).

Taliban rule will ultimately depend on the support the group is able to garner from international partners, especially Pakistan and Iran.

In this scenario, we therefore assume that the Taliban would not be able to increase their security apparatus to the size, or at the pace, necessary to maintain satisfactory levels of security. Such a shortcoming is likely to spawn an insurgency and see the growth of extremist groups set on targeting both the Afghan population and Chinese workers and representations in Pakistan. It could also lead to a rise in extremist organisations aiming to target Russia, or Europe. This in turn would sour relations with Iran, Pakistan, China and Russia, undermine Chinese investments and hence bar access to potential income from REE exports (33). Financially and economically, the Taliban regime would therefore find itself in dire straits. In addition, they will not be prepared to manage natural disasters, such as droughts and floods, whose frequency is projected to increase significantly over the next decade due to climate change (34). This in turn could push more Afghans into emigration. In this scenario, Afghanistan would accordingly see a gradual descent into the state of civil war the country experienced in the 1990s when the Taliban controlled about two-thirds of Afghan territory. It was under these conditions that al-Qaeda found refuge there. In the 2020s, matters would be different in that ISKP and others would not operate from Afghanistan with the government’s permission – but such groups would operate from Afghanistan all the same.

Scenario: Stability, at last

Probability: 30%

A cheaper and more sustainable path to regime consolidation would begin with the Taliban making ideological concessions. This would start with the regime striking political deals with opponents such as the National Resistance Front and a progressive move towards the establishment of an inclusive political structure that incorporates representatives from a broad spectrum of Afghan society. It would require the Taliban to loosen restrictions on the role of women in public life. While going down this road would not solve all of the regime’s problems, it would significantly reduce popular opposition to the Taliban’s rule. In this way, the Taliban would free itself up to focus on the extremist groups that risk challenging not just their rule, but undermining their relations with China, Iran, Russia and Europe. In this scenario, opposition from extremist groups is likely to increase further, because the regime would be seen as even more of an ideological opponent. Extremist groups such as ISKP already view the Taliban regime as nationalist and therefore in opposition to their pan-Islamic agenda. Making concessions on the ideological front would bolster a narrative that casts the Taliban as not sufficiently committed to the establishment of a state based on Islamic principles. This would also push the more radical factions of the Taliban, who remain dedicated to hardline policies and oppose the necessary compromises, towards ISKP or entirely new entities espousing a radical political vision. A factor that could further weaken the Taliban is the wider internationalisation of ISKP, attracting Islamic State (IS) fighters from other battlefields. Early signs of movement of militants from Syria and Iraq to Afghanistan are already visible, and the appointment of a commander of Syrian or Iraqi, rather than Afghan origin, provides further evidence of this trend (35). Lack of intelligence cooperation with international partners, as is the case now, means that it will be even easier for such extremist elements to infiltrate Afghanistan. A perceived weakening of Russia in Syria could bolster groups such as Tahrir al-Sham and, by extension, like-minded groups elsewhere. Under these circumstances, ISKP has a chance of replicating the attack frequency of the years before 2018 when it nearly matched the Taliban (36). Under its new commander, Sanaullah Ghafari (also known as Shahab al-Muhajir), violence is likely to shift away from the Taliban’s largely rural, improvised explosive device (IED) terror campaign, towards a sectarian, identitarian conflict targeting officials, foreign representations and minorities such as the country’s Shia Muslims. Ghafari also has other skills that do not bode well for the Taliban: experience in the production of synthetic drugs as a source of revenue. As Afghanistan is already displaying signs of a shift away from opium poppy towards synthetic drug production, ISPK would be well-placed to exploit the global demand for substances such as methamphetamines to fund its resurgence.

Data: The Asian Foundation, 2019

That said, in this scenario the Taliban would face a smaller insurgency than in the ‘Civil war, reloaded’ scenario, meaning that their need to increase their security personnel would be less urgent, and therefore, their financial needs less pressing. Given a less stringent approach to ideology, this could also re-open access to funding from international donors such as the EU and attract investors. But the Taliban would have to keep a sufficient degree of stability in place before China would seek to expand its mining rights for lithium, or link Afghanistan into the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a branch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that has seen Beijing invest billions into the development of Pakistan’s infrastructure (37).

Gaining access to funds is a political and security priority for the Taliban.

One option to keep ISKP in check is to ensure that Afghan security personnel receive incomes that are high enough to undermine the temptation of alternative affiliations. In addition to prioritising financial buyouts and allegiances, the Taliban will need to ensure that technocrats, capable of maintaining service delivery, remain in the country. While the suspension of aid has meant that Afghan civil servants have gone unpaid for months (38), the Taliban will need to prioritise combining the establishment of a more inclusive political structure with the delivery of public goods in order to gain the acquiescence, if not pervasive support, of the Afghan public. Such performance-based legitimacy (premised alongside the delivery of public services) rather than the resort to coercion and ideology, would ultimately pave the way towards a more reliable form of regime consolidation. But as the preceding analysis suggests, this ‘best case’ scenario by no means constitutes an easy option for the Taliban regime.

What does this mean for the EU?

Our analysis shows both that Afghanistan has a high chance of relapsing into conflict, and that this trajectory is not inevitable. Indeed, we find that meeting the EU’s benchmarks (see box below) would likely grant the Taliban the highest chance of regime stability while, ultimately, improving living conditions for the Afghan population.

|

Council of the European Union: Benchmarks for policies and actions for future engagement with the Taliban In September 2021, the EU specified five benchmarks as criteria for its engagement with the Taliban government (39). These stipulate that the Taliban: (i) allows the safe, secure and orderly departure of all foreigners and Afghans who wish to leave the country; (ii) promotes, protects and respects human rights, particularly for women and minorities, the rule of law and fundamental freedoms; (iii) enables free access for humanitarian operations (including for female staff) in line with international humanitarian law; (iv) prevents anyone from financing, hosting or supporting terrorist activity from inside Afghanistan and ceases all ties with international terrorism; and (v) lastly, establishes an inclusive and representative government through negotiation) (40). |

But current signs, such as security sweeps and the hunting down of individuals opposed to their rule, suggest that on the suppression of crime, conflict and corruption ideological path (41). With a view to these dynamics, the EU essentially faces a ‘wicked problem’ (42) in Afghanistan: while its approach may ultimately be vindicated by the Afghan population’s open rejection of the Taliban regime, this would come at an immense human cost. It would also mean that Afghanistan would become a destabilising force in the EU’s extended eastern neighbourhood, including Central Asia, a source of significant migration to Europe, and a breeding ground for extremist groups. Given this projection, promoting conditions that will set Afghanistan on a path to relative stability is an international priority, but one that ultimately hinges on the Taliban regime’s willingness to make concessions.

With a view to this analysis, we propose the following policy considerations:

› Convince international partners to provide conditional budgetary support to the Taliban regime: As it stands, the Taliban’s weakest point is its financial need. With the Afghan economy in free fall and swathes of the population facing a dire food crisis, gaining access to funds is a political and security priority for the Taliban. While the EU has indicated that it will refrain from providing direct financial support to the Taliban regime, liaising with partners to offer conditional support to the Taliban would allow the Union to help forestall the collapse of the Afghan state and the further deterioration of the humanitarian crisis currently underway.

› Support mediation efforts by Iran and Pakistan: Both states have attempted to encourage a peace deal between the Taliban and its Afghan opponents, albeit without success so far. However, the fact that these key regional players have made mediation attempts indicates that Iran and Pakistan share the assessment that the chances of stability, a key regional priority, are highest if an inclusive Afghan government is established.

› Provide political support for Afghan opposition leaders: The legitimacy of Afghan opposition leaders in mediation attempts can be bolstered if the EU offers some form of international support to these actors and seeks to persuade all parties of the benefits of an inclusive approach. This would require the EU to take an active stance of support towards Afghan representatives willing to engage in negotiation with the Taliban and thereby signal an indirect engagement with the Taliban.

› Monitor the security situation in Afghanistan to detect an escalation early on: With counter-terrorism among its top political and security priorities in Afghanistan, the EU should pay close attention to the movement of European ‘foreign fighters’ from Syrian and Iraqi battlefields towards Afghanistan. Such migration is a likely indicator of the strengthening and expansion of ISKP, with immense implications for the Taliban’s ability to deliver order and suppress conflict in Afghanistan.

› Monitor the methamphetamine market: An increase in the production and sale of methamphetamines in Afghanistan should be closely monitored and read as an early warning sign for the expansion of groups such as ISKP. Elevated rates of production of substances such as crystal meth would indicate an expansion of a key source of income for a range of extremist groups operating within Afghanistan, pointing to a rise in conflict probability.

› Prepare for increased migration to Europe of Afghan asylum seekers: Already, Afghans constitute one of the largest refugee populations in the world with 2.6 million living outside their country of origin, Today the highest proportion of asylum requests in the EU are made by Afghan nationals. Both Pakistan and Iran, two of Afghanistan’s immediate neighbours, already host millions of Afghan refugees and are unlikely to welcome a further wave of migrants. With a further deterioration of the humanitarian and political crisis at hand, more Afghans are likely to leave their homes. Preparing for increased migration would also allow the EU to prevent Afghan refugees being used as a political bargaining chip by contending regional forces.

References

1. ‘Gorbachev, leader who pulled Soviets from Afghanistan, says U.S. campaign was doomed from start’, Reuters, 17 August 2021 (https:// www.reuters.com/world/india/gorbachev-leader-who-pulled-soviets- afghanistan-says-us-campaign-was-doomed-2021-08-17/).

2. Magruk, A., ‘Concept of uncertainty in relation to the foresight research’, Engineering Management in Production and Services, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2017, pp. 46-55.

3. Walter, B.F., ‘Conflict relapse and the sustainability of post-conflict peace’, World Development Report 2011 - Background Paper, 13 September 2010 (https://web.worldbank.org/archive/website01306/web/ pdf/wdr%20background%20paper_walter_0.pdf).

4. Gates, S., Mokleiv Nygård, H.M. and Trappeniers, E., ‘Conflict Recurrence’, Conflict Trends, PRIO, Oslo, February 2016 (https://www.prio. org/publications/9056); UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset, Vol. 4, 2009).

5. Collier, P. et al., Breaking the Conflict Trap: Civil war and development policy,World Bank, Washington, D.C., 2003.

6. ‘Is the Taliban’s campaign against the Islamic State working?’, The Diplomat, 10 February 2022.

7. Buhaug H. and Gates, S., ‘The geography of civil war’, Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 39, No 4, 2002, pp. 417-433.

8. Collier, P., Hoeffler, A. and Söderbom, M., ‘Post-Conflict Risks’, Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 45, No. 4, July 2008, pp. 461–78. Fearon, D. and Laitin, D.D., ‘Ethnicity, insurgency, and civil war’, American Political Science Review, Vol. 97, No 1, February 2003, pp. 75–90; Von Einsiedel,S. et al., ‘Civil war trends and the changing nature of armed conflict’, Occasional Paper No 10 , UN University Centre for Policy Research, 2017.

9. World Bank Group, ‘Climate Risk Country Profile: Afghanistan’, Washington, 2020 (https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/ publication/660566/climate-risk-country-profile-afghanistan.pdf).

10. BBC News, ‘Afghanistan: How much opium is produced and what’s the Taliban’s record?’, 25 August 2021 (https://www.bbc.com/news/world- asia-58308494).

11. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, ‘Drug situation in Afghanistan 2021: Latest findings and emerging threats’, 2021 (https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/Afghanistan/ Afghanistan_brief_Nov_2021.pdf).

12. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), ‘Methamphetamine in Europe’, EMCDDA-Europol Threat Assessment, 2019 (https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/ publications/12132/20195788_TD0119853ENN.pdf).

13. Doyle, M. W. and Sambanis, N., Making War and Building Peace: United Nations Peace Operations, Princeton University Press, NJ, 2006; Walter, B.F., ‘Does conflict beget conflict? Explaining recurring civil war’, Journal of Peace Research, Vol 41, No 3, May 2004, pp. 371–88; Quinn, J.M., Mason, T.D. and Gurses, M., ‘Sustaining the Peace: Determinants of civil war recurrence’, International Interactions, Vol. 33, No 2, April 2007, pp. 167–93; Collier, P., Hoeffler, A. and Söderbom, M., ‘Post-Confcict Risks’, Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 45, No 4, July 2008, pp. 461–78; Kreutz, J., ‘How and when armed conflicts end: Introducing the UCDP Conflict Termination Dataset’, Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 47, No. 2, March 2010, pp. 243–50.

14. United Nations Development Programme, ‘Human Development Reports:Afghanistan’ (https://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/AFG).

15. United Nations Development Programme, ‘Economic Instability and Uncertainty in Afghanistan after August 15’, 9 September 2021 (https:// www.undp.org/publications/economic-instability-and-uncertainty- afghanistan-after-august-15).

16. OCHA, ‘Climate Risk Country Profile – Afghanistan’, 8 December 2020 (https://reliefweb.int/report/afghanistan/climate-risk-country-profile- afghanistan).

17. Ibid.

18. Ministry of Mines & Petroleum, Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, ‘Mining Sector Roadmap’, 2019; United States Geological Survey, ‘A summary of data collected by the U.S. Geological Survey at Dasht-e-Nawar, Afghanistan, in support of lithium exploration, June-September 2014’,May 2015; World Bank, ‘Transitional Islamic State of Afghanistan Mining as a source of growth’, 2004.

19. ‘Mining, metals & minerals: Lithium’, Statista, 2022 (https://www. statista.com/statistics/1220158/global-lithium-demand-volume-by- application/); United States Geological Survey, ‘Lithium Statistics and Information’, US Department of the Interior, 2021.

20. Treadgold, T., ‘Copper and lithium compete for the title of “new oil”’, Forbes, 23 April 2021 (https://www.forbes.com/sites/timtreadgold/2021/04/23/copper-and-lithium-compete-for-the-title- of-new-oil/?sh=33d8ab02682d).

21. Johnson, I., ‘How will China deal with the Taliban?’, Council on Foreign Relations, 24 August 2021 (https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/china- afghanistan-deal-with-taliban); Najafizada, E., ‘Chinese miners in talks to access vast Afghan lithium reserves’, Bloomberg, 25 November 2021 (https://www.bloombergquint.com/china/chinese-firms-show-interest- in-afghanistan-s-mineral-reserves#:~:text=Afghanistan%20is%20 sitting%20on%20deposits,transition%20away%20from%20fossil%20 fuels).

22. International Energy Agency, ‘Reliable supply of minerals’, in The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions, May 2021 (https://www.iea. org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions/ reliable-supply-of-minerals).

23. United Nations Mission in Afghanistan, ‘Afghanistan: protection of civilians in armed conflict – Annual Report 2018’, February 2019 (https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/afghanistan_ protection_of_civilians_annual_report_2018_final_24_feb_2019.pdf); ‘Afghanistan: protection of civilians in armed conflict – Annual Report 2020’, February 2021 (https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/ resources/afghanistan_protection_of_civilians_report_2020.pdf).

24. The Asia Foundation, A Survey of the Afghan People – Afghanistan in 2019, 2019 (https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/2019_ Afghan_Survey_Full-Report.pdf).

25. PopulationPyramid.net, ‘Afghanistan’ (https://www.populationpyramid.net/afghanistan/2025/).

26. Felbab-Brown, V., ‘Will the Taliban regime survive?’, Brookings, 31 August 2021 (https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from- chaos/2021/08/31/will-the-taliban-regime-survive/).

27. International Crisis Group, ‘Watch List 2021: Autumn Update’, 7 October 2021 (https://www.crisisgroup.org/global/watch-list-2021-autumn- update); The World Bank, ‘The World Bank in Afghanistan’, 2021 (https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/afghanistan/overview#1).

28. Kent, S., ‘Words of Estimative Probability’, Autumn 1964 (https:// www.cia.gov/static/0aae8f84700a256abf63f7aad73b0a7d/Words-of- Estimative-Probability.pdf).

29. Quinlivan, J.T., ‘Force Requirements in Stability Operations’, Parameters, Vol. 25, No 1, 1995.

30. ‘The World Bank in Afghanistan’, op.cit.

31. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crimes, ‘World Drug Report 2021’, United Nations Publications, June 2021.

32. Ministry of Mines & Petroleum, Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, ‘Mineral Resources in Afghanistan’, 2020. (https://www.pdac.ca/docs/ default-source/conventions/2020-convention/presentation-reception- rooms/minerals-book---afghanistan-momp.pdf?sfvrsn=8259698_0).

33. Sacks, D., ‘Why major Belt and Road investments are not coming to Afghanistan’, Council on Foreign Relations, 24 August 2021 (https:// www.cfr.org/blog/why-major-belt-and-road-investments-are-not- coming-afghanistan).

34. OCHA, ‘Climate Risk Country Profile – Afghanistan’, 8 December 2020 (https://reliefweb.int/report/afghanistan/climate-risk-country-profile- afghanistan).

35. ‘MI5 chief Ken McCallum: British extremists are travelling to Afghanistan’, The National, 21 February 2022 (https://www. thenationalnews.com/world/uk-news/2022/02/21/mi5-chief-ken- mccallum-british-extremists-are-travelling-to-afghanistan/).

36. ‘Afghanistan: protection of civilians in armed conflict – Annual Report 2018’, op.cit.

37. Shah, S., ‘China’s Xi Jinping launches investment deal in Pakistan’, Wall Street Journal, 20 April 2015 (https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-xi- jinping-set-to-launch-investment-deal-in-pakistan-1429533767).

38. International Crisis Group, ‘Stopping state failure in Afghanistan’, Commentary/Asia, 27 January 2022 (https://www.crisisgroup.org/asia/ south-asia/afghanistan/stopping-state-failure-afghanistan).

39. Council of the European Union, ‘Council Conclusions on Afghanistan’, 11713/2/21, 15 September 2021 (https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/ document/ST-11713-2021-REV-2/en/pdf).

40. Ibid.

41. France 24, ‘Taliban ban Afghans from evacuating amid massive security sweep’, 28 February 2022 (https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20220228-taliban-ban-afghans-from-evacuating-amid-massive- security-sweep).

42. ‘Wicked problems’ are problems made difficult because of, among other things, contradictory and changing requirements, complex interdependencies, multiple stakeholders, solutions that are neither right nor wrong, and conditions where the effort to solve one aspect of the problem may reveal or create other problems. See: Kremer, F.D., ‘Irregular conflict and the wicked problem dilemma: Strategies of imperfection’, PRISM, Vol. 2, No 3, July 2011.