Within the toolbox of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), sanctions have indisputably become the instrument of choice. Even before the invasion of Ukraine started on 24 February 2022, observers highlighted that most CFSP decisions concerned the imposition, renewal or updating of sanctions (1). Because of their versatility, Brussels employs sanctions to respond to a vast array of foreign policy challenges: democratic backsliding, human rights violations, the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, terrorism, the misappropriation of state assets, and even human trafficking. As with all controversial tools, sanctions are subject to great scrutiny, and their usefulness is ultimately judged against their performance. In addition to denouncing their negative impact on the population, detractors typically highlight their lack of effectiveness. But how do we know whether and when sanctions are effective? Despite the growing reliance on sanctions, and the sizeable amount of analysis devoted to the topic, there is no universally agreed methodology for assessing their effectiveness. However, after Brussels put together an exceptionally hard sanctions package in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last February, the question of how to evaluate sanctions’ effectiveness has become all the more pressing for the EU. These sanctions come on top of the restrictions imposed in 2014 in reaction to the annexation of Crimea and the destabilisation of the Donbas. While 2014 was identified as a turning point in EU sanctions policy (2), the waves of sanctions regimes adopted in close succession since February 2022 have been labelled a sanctions ‘revolution’ (3).

Mainstream analyses typically portray the sanctions regime as unsuccessful. However, most assessments are based on the observation that Moscow has not altered its foreign policy course or withdrawn from Crimea, and continues its military actions in the rest of Ukraine. This Brief proposes an alternative assessment framework. First, we identify the purposes pursued by sanctions and the rationales that guide them. Second, we rely on a broader set of criteria to produce a more accurate picture of their effectiveness. This helps us develop a better understanding of the purposes and effectiveness of EU sanctions on Russia. The Brief starts by outlining the complex organisation of the EU sanctions regime against Russia, which is divided into several sub-regimes. Next, it investigates the rationale behind sanctions design. Finally, it takes stock of their performance in the case of Russia.

EU sanctions regimes against Russia

The 2022 sanctions against Russia build upon a sanctions regime first established in March 2014 and expanded in three waves over the same year. The 2014 package circumscribes relations with Russia with different types of measures: diplomatic sanctions, freezing of assets and travel bans on individuals, and economic and financial restrictions. A peculiarity of the 2014 sanctions is that they were compartmentalised into three parallel, albeit separate, sanctions regimes:

- A first sanctions regime addressing the annexation of Crimea entails a full export ban on the peninsula — a measure otherwise absent from EU sanctions policy – alongside severe restrictions on exports and financial transactions. It also includes a prohibition for EU vessels to call at Crimean harbours, as well as assets freezes and visa bans on selected actors.

- Another sanctions regime in support of the territorial integrity of Ukraine responds to Moscow’s backing of separatist forces. Following the downing of Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 over Ukraine in July 2014, the EU restricted access to capital markets for some Russian banks and companies, banned trade in arms and dual-use goods, and limited access to some technologies and services for oil production and exploration.

- Finally, an often overlooked sanctions regime addresses the misappropriation of state assets by the Ukrainian leadership ousted by the protests of 2014. While this set of sanctions targets the entourage of former Ukrainian President Yanukovych, it is nevertheless linked to Russia as the individuals listed are now based on its territory.

After 2014, the EU’s condemnation of the Kremlin’s policies did not translate into any further tightening of the existing regime. Instead, the EU included Russian targets in thematic sanctions regimes addressing cyber-attacks, chemical weapons and human rights breaches. While these sanctions regimes are disconnected from any territory, their common denominator is the presence of Russian targets (4).

The Russian invasion of Ukraine launched on 24 February 2022, preceded by the Duma’s recognition of the provinces of Donetsk and Luhansk as independent, triggered several new waves of sanctions adopted in close succession. This entailed the tightening of the 2014 sanctions regime supporting the territorial integrity of Ukraine and the introduction of a new one.

After Russian forces penetrated into Donetsk and Luhansk (5), Brussels banned the import into the EU of goods originating in these territories — unless granted a Ukrainian certificate of origin — but also trade in goods and technology, as well as services in the transport, telecommunications, tourism, energy, and mineral exploitation sectors. For its part, the sanctions regime in support of the territorial integrity of Ukraine experienced no less than 14 upgrades from February to July 2022 (6). The full suspension of the visa facilitation agreement with Russia in September 2022 (7) was followed in October 2022 by further restrictions, including on technology exports (8).

The resulting sanctions regime is atypical in its setup. Routinely, sanctions regimes see the addition of new goals as the situation evolves. The ongoing sanctions regime on Belarus, for example, responds to actions as diverse as internal repression, aiding illegal migration and involvement in the aggression against Ukraine. By contrast, current EU sanctions on Russia consist of multiple regimes organised according to the types of measures imposed. The regime on Crimea imposes an economic embargo on the peninsula. The regime on Donetsk and Luhansk extends the embargo to these territories. The regime in support of Ukraine’s sovereignty entails listings of individuals and entities responsible for military operations, holding an illegal referendum and breaching international humanitarian law.

Mechanisms of sanctions operation

Mainstream analyses measure the success of sanctions by the extent of deprivation to which the target is subjected and the modifications observed in its political behaviour. Economic damage and political impact are distinct effects which ought to be assessed separately. Both effects are not of equal importance: economic damage is considered a means to an end, i.e. behavioural change. Importantly, economic analyses of sanctions reveal no direct correlation between the magnitude of the economic hardship inflicted on the target and the success of sanctions. Even bans causing severe economic disruption may fail to effect compliance (9).

To assess the effectiveness of sanctions, one must first establish their actual intent.

But how is this behavioural change to be achieved? Two modes of operation can be distinguished: the classical model aims at affecting the target economy across the board: sanctions are expected to generate sufficient economic deprivation to galvanise the population against the leaders, compelling them to comply with sender demands to restore wealth or face being unseated (10).

An alternative, selective logic emphasises how sanctions attempt to alter the power balance within the target country. There, the measures are meant to favour and mobilise the elites receptive to sender demands, while disadvantaging the ruling regime and their associates, in a bid to sway the elites away from the ruling regime and towards the opposition (11). Both approaches entail an economic element. They rely on the idea that business, military and religious elites back the ruling regime because they benefit from it politically and economically. As association to the regime ceases to be beneficial, they will withdraw their support from the leadership and transfer their allegiance elsewhere. Hence, sanctions discourage elites from supporting the ruling regime by making their association less lucrative and attractive (12). At the same time, they disadvantage the ruling regime by reducing the revenue available to nurture elite loyalty, to fund the repression of dissenting elements and to continue the policies condemned by the sender.

Goals of EU sanctions on Russia

Policy effectiveness ought to be assessed against the intended goals of the measures. Thus, to assess the effectiveness of sanctions, one must first establish their actual intent (13). What are the objectives of CFSP sanctions regimes? The justification for sanctions imposition in CFSP acts and the criteria determining the targets provide some insights.

Sanctions will permanently impair Russia’s economic and technological potential.

The same is true for statements by top decision-makers, such as the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy/ Vice President (HR/VP) Josep Borrell and Commission President Ursula von der Leyen.

The sanctions regimes enacted following the annexation of Crimea and the destabilisation of Eastern Ukraine called for the withdrawal of troops, access for international monitors and negotiations between Ukraine and Russia. Designation criteria targeted those ‘responsible for actions which undermine or threaten the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine’ (14). The Donetsk and Luhansk sanctions regime was adopted after the EU had repeatedly warned Russia of ‘massive consequences and severe costs, including a wide array of sectoral and individual restrictive measures’ in case of further aggression against Ukraine (15). Condemning the recognition of Donetsk and Luhansk as a breach of international law, the Council urged Russia to ‘reverse the recognition, uphold its commitments in finding a peaceful settlement to this conflict, abide by international law and return to the discussions within the Normandy format and the Trilateral Contact Group’ (16). The designation criteria of the territorial integrity regime were amended to include individuals and entities ‘supporting and benefiting from the Russian government’, ‘providing a substantial source of revenue to it’, or ‘associated with listed persons or entities’ (17).

When Ursula von der Leyen first announced sanctions following the invasion of Ukraine, she claimed they aimed to ‘cripple Putin’s ability to finance his war machine’ (18). The Commission President described the fourth package of sanctions as aiming ‘to further isolate Russia and drain the resources it uses to finance this barbaric war’. She spoke of ‘pressuring Russian elites close to Putin as well as their families and enablers’ and mentioned the determination to ‘stop the group close to Putin and the architects of his war’ and ‘hit a central sector of Russia’s system, deprive it of billions of export revenues and ensure that our citizens are not subsidising Putin’s war’ (19). For his part, HR/VP Borrell highlighted that, in addition to limiting the economic resources of the target country, sanctions fulfil a symbolic function by messaging the unacceptability of its behaviour: ‘The political signal is now very strong: Europe is willing to take significant economic risks to coerce Russia for its invasion and to extend its political margin of manoeuvre vis-à-vis Moscow in the future’ (20).

While sanctions are generally presented as aimed at promoting compliance with sender demands, this is not their only — and sometimes not even their primary — objective (21). They also fulfil a normative function directed at audiences beyond the targeted leadership (22). They demonstrate to both a domestic audience and the international community the sender coalition’s determination to defend global norms (23). In contrast with compliance, the achievement of these goals does not depend on target behaviour but can be accomplished with the mere imposition of the sanctions. In the case of the EU, the joint sanctions imposition under the CFSP enhances its presence on the world stage as an advocate of international law, democracy and human rights, as demonstrated by the EU’s discourse. It allows the EU to portray itself as a unified entity – ‘the EU stands firmly with the brave people of Ukraine’— thanks to ‘sanctions we have adopted’ (24). It also aligns Brussels with its global allies in what is presented as a joint endeavour: ‘the EU and our partners in the G7 continue to work in lockstep to ramp up the economic pressure against the Kremlin’ (25). The normative intent of sanctions finds reflection in the EU discourse, as a price to pay for breaching internationally agreed principles: ‘Russia cannot grossly violate international law and, at the same time, expect to benefit from the privileges of being part of the international economic order’ (26). Closely connected to the magnitude of the violation, public support for the sanctions against Russia is high on average, although it varies across EU Member States (27).

Impacts on the Russian economy

Sanctions are routinely credited with success when they appear to contribute to the achievement of stated policy goals. The yardstick is an ‘observable change in behaviour’, with policy outcomes assessed ‘against the stated policy goal of the sender country’ (28). Having established that sanctions fulfil various functions, that they follow more than one logic, and that they display both economic and political effects, we will use a these aspects into account. As the sanctions packages have been in force for a few months, a preliminary assessment can be attempted.

Data: Rosstat, Bank of Russia, 2022

Economic sanctions have caused a severe economic crisis in Russia. The Russian Central Bank expects that in the fourth quarter of 2022 the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) will shrink by 8.5 % to 12 % (29). Although the effect of sanctions is unfolding more slowly than predicted initially, the depth of the recession is comparable with the fallout from the global financial crisis of 2008-2009. Yet, in contrast to previous economic crises, which were predominantly driven by oil price crashes, a swift recovery is unlikely. Sanctions will permanently impair Russia’s economic and technological potential and lead to a long-lasting decline in living standards among the population, while reducing the economic resources available to the elites.

The delayed effect of the sanctions can be partly attributed to Russia’s efforts to strengthen its resistance to economic pressure, a priority for the Kremlin after the 2014 sanctions (30). The Central Bank of Russia introduced alternatives to Western financial messaging services (SWIFT), compelled Western credit card providers to integrate into a Russian payments system, and shifted some of its reserves into other currencies (31). However, Russia did not anticipate the severity of the 2022 sanctions and the unanimity of G7 countries. After the US imposed new sanctions on Russia in 2018, the Central Bank shifted reserve assets from US dollars to euros and yen as it did not expect the EU and Japan to freeze them (32). Some reforms, like import substitution, proved less fruitful than the Kremlin hoped: in particular, Russia’s economy remained highly dependent on Western technological imports (33).

During the first six months under the new sanctions regime, the collapse of imports led to massive disruptions in the Russian industrial sector. The combined effect of financial sanctions, a strict technology embargo as well as the withdrawal of more than 1 000 companies (34) restricted Russia’s access to components, materials and machinery from abroad. In March and April, imports from sender countries fell by 60 % to 90 %, (35) while imports from other countries dropped as well. Much of this drop was due to indirect disruptions of trade links, high uncertainty and reputational concerns of multinational companies, rather than to formal bans. Some of these effects are temporary, causing a modest recovery of imports from senders and non-senders alike, although they have remained significantly below pre-sanction levels. Export controls on technology have had the most dramatic impacts. Restrictions on machinery and components like chips, but also on software and even low-tech goods, have ample reach as their use extends across sectors (36). The lack of machinery, materials and components was particularly consequential in manufacturing, where Russia’s supply chains were the most complex and internationalised. Russia’s automotive and locomotive industry, its aerospace sector and production of electrical appliances almost came to a standstill after sanctions were imposed, and output has shown very little sign of recovery since. Moreover, restrictions on technology are affecting arms manufacturers, which lack imported components, such as microchips and guidance systems, necessary to replace advanced weapons (37).

In contrast to imports, Russia’s exports boomed after February 2022. Thanks to high energy prices, coupled with the delayed implementation of the EU oil embargo and the decline in imports, this led to an unprecedented current account surplus of $127 billion from March to July 2022 (38). The surge in exports helped the Russian regime to stabilise the economic situation in the first weeks under sanctions. In combination with the introduction of strict capital controls, the current account surplus allowed the Central Bank to strengthen the rouble, making imports cheaper. This helped to gradually bring down inflation, taking some pressure off the real incomes of the Russian population. While the Central Bank cannot access its reserves in dollars, euros and yen due to sanctions, it was able to support the rouble by ordering Russian exporters to sell their export revenue on Moscow’s foreign exchange market for roubles. While Russia is unlikely to experience a currency crisis anytime soon, EU restrictions on Russian commodities like timber, steel, coal and gold have caused disruption in the targeted sectors in Russia and contributed to the country’s economic decline (39). Export restrictions also directly affect Russia’s influential businessmen, many of whom have built their wealth on the export of natural resources. The oil and oil products embargo that will come into effect in December 2022 and February 2023 is expected to deepen Russia’s economic crisis and particularly impact export and government revenues.

Impacts on Russia's budget

Russia’s federal budget is the Kremlin’s most important tool for the distribution of resources within the country, paying for the military and the security apparatus, subsidies for well-connected elites as well as social policies directed at the population. Since President Putin took office in 2000, fiscal and monetary policy has been highly conservative, avoiding deficits and public debt as much as possible. The government introduced a strict fiscal rule in 2017, successfully adapting the budget to lower long-term oil prices (40). This has helped Russia to build fiscal buffers in the National Welfare Fund (11 trillion roubles, or 8 % of GDP) (41).

Data: Rosstat, BOFIT, 2022

Russia significantly increased its fiscal spending in the first half of 2022, both to fund the war against Ukraine and to counter the economic effects of sanctions. Finance Minister Anton Siluanov claimed that ‘huge’ resources were necessary for the war (42). Even before the announcement of a partial mobilisation on 21 September, Russia’s Ministry of Finance estimated that the defence budget in 2022 would reach 4.7 trillion roubles, 1.2 trillion more than expected. For 2023 and 2024, Russia plans to spend 6.3 % of GDP on defence and national security in the federal budget alone, almost 50 % more than expected before the war (43). In addition, significant spending will accrue in other parts of the budget, given the involvement of mercenary groups and Chechen forces in Ukraine, as well as subsidies for the arms industry.

The fear of retribution has effectively prevented visible power shifts within the regime.

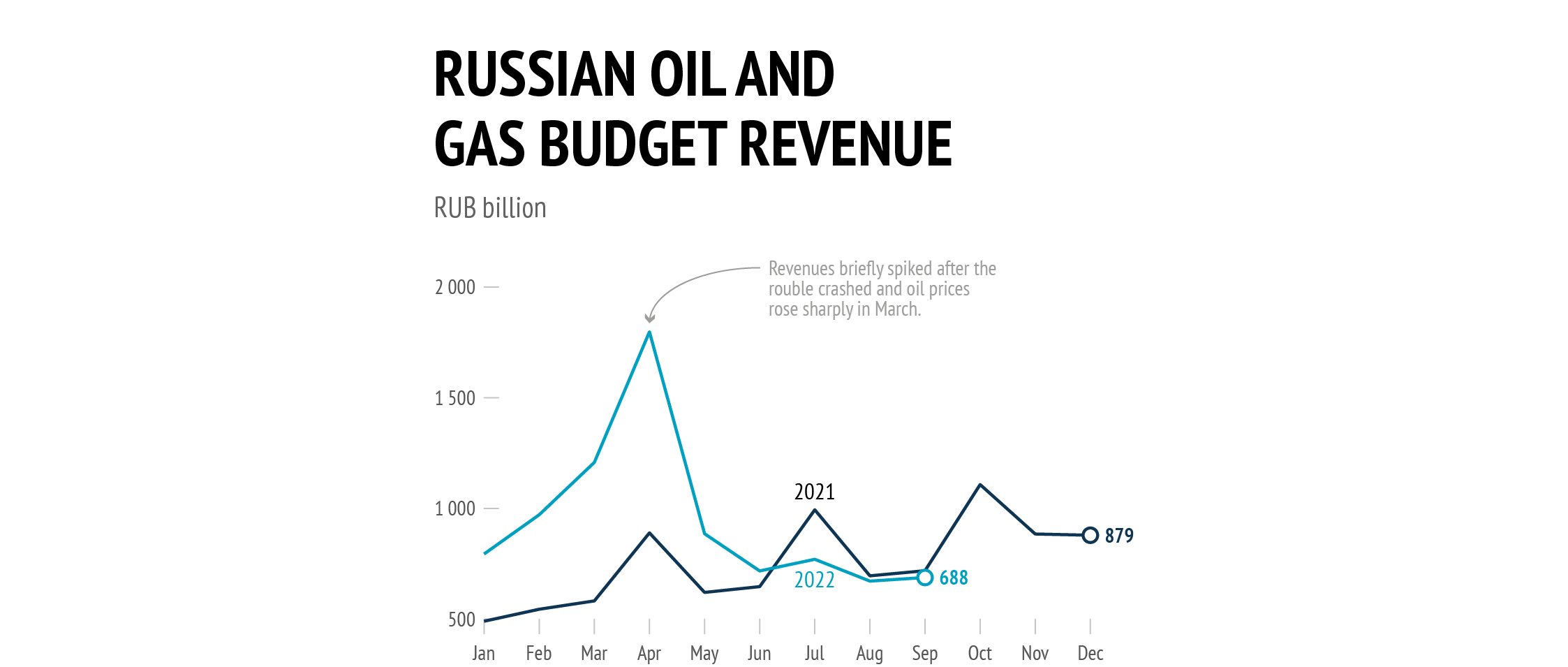

At the same time, budget revenue is shrinking due to the economic crisis triggered by sanctions. Non-energy tax revenues, which make up around 60 % of Russia’s budget, were down 14 % in March-July 2022 compared to the same period in 2021, despite annual inflation reaching 17.8 % in March (44). Revenue from oil and gas briefly spiked in March and April due to high oil prices and a weak rouble exchange rate. However, starting in July, revenue from oil and gas was below the previous year’s levels, as a stronger rouble and lower gas exports weighed on exports. In theory, the Russian state cannot run out of funds, as the Central Bank can print roubles and the Kremlin can raise taxes. Nevertheless, the ability to use these options is de facto constrained by economic and domestic policy risks (45).

Data: Russian Ministry of Finance, 2022

Sanctions have severely limited the Kremlin’s fiscal room for manoeuvre, forcing it to make tough choices between funding the war, social services, domestic repression and serving elites’ interests. However, prior to the 2022 sanctions, the fiscal situation was very favourable for Moscow and the budgetary situation will not become critical for the next one or two years. The Kremlin can still mobilise additional resources by redirecting spending within the budget, resorting to the National Welfare Fund, increasing domestic borrowing, and printing money— at least temporarily — if the crisis deepens.

Impact on population and elites

Both elites and the population in Russia have felt the effects of sanctions, albeit to varying degrees.

Sanctions have most strongly disadvantaged economic elites with business ties to the West: many of the country’s most affluent businessmen lost significant wealth after being listed by the EU and the US. However, their political influence had sharply diminished under Vladimir Putin’s tenure. While some of the wealthiest businessmen criticised the war initially (46), they fell silent after the state cracked down on them. This was the case of the openly critical businessman Oleg Tinkov who was expropriated and received warnings from the security services (47). Among government elites, many growth-oriented government technocrats saw their work reduced to tatters in February 2022, which produced visible frustration among them (48). Yet, there have been no defections from key positions of the government. Elites critical of the war have to worry about both repression orchestrated by the Kremlin and attacks from other elites competing for power. The fear of retribution has effectively prevented visible power shifts within the regime. At the same time, the war has enhanced the prominence of the security apparatus at the expense of other groups. Among Russia’s top elites, no discernible cleavages or alternative power centres have emerged.

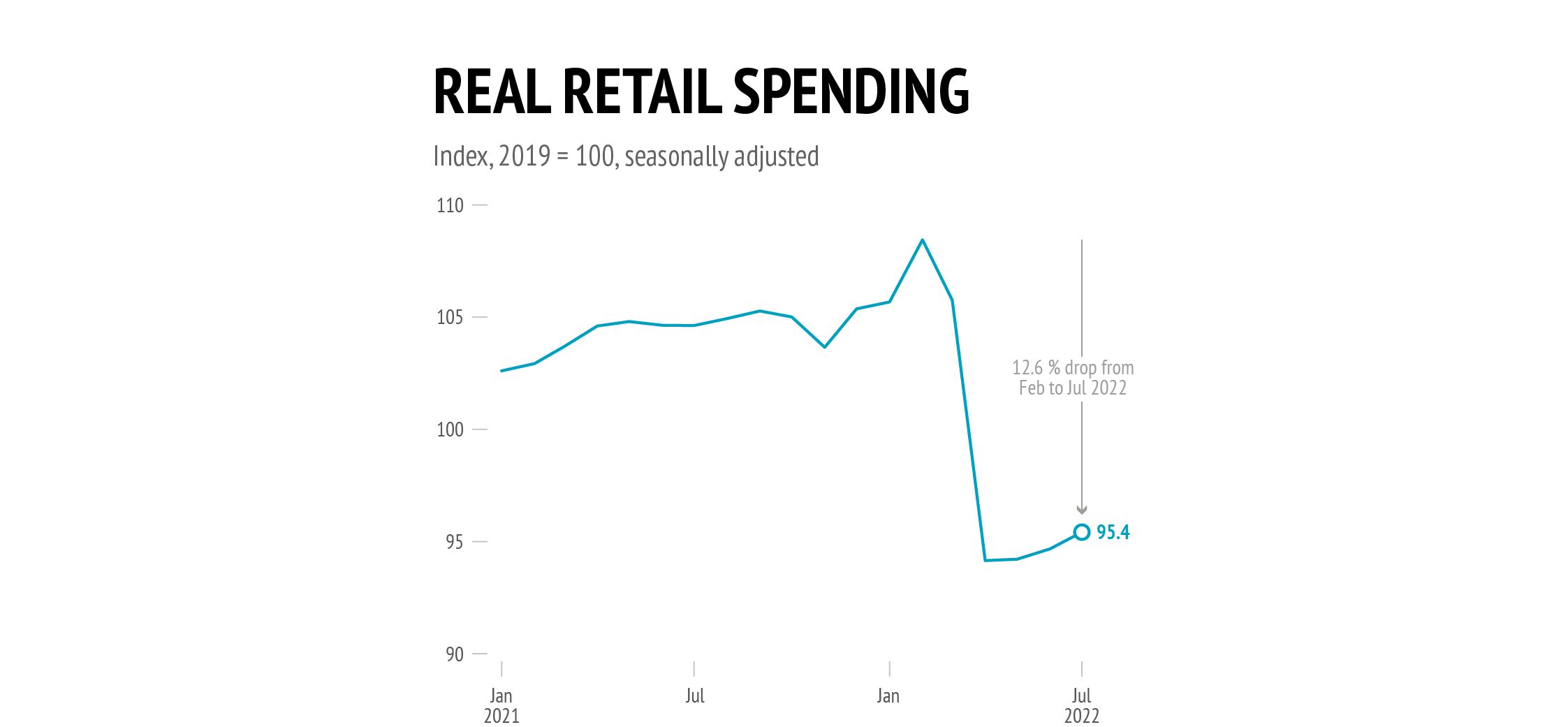

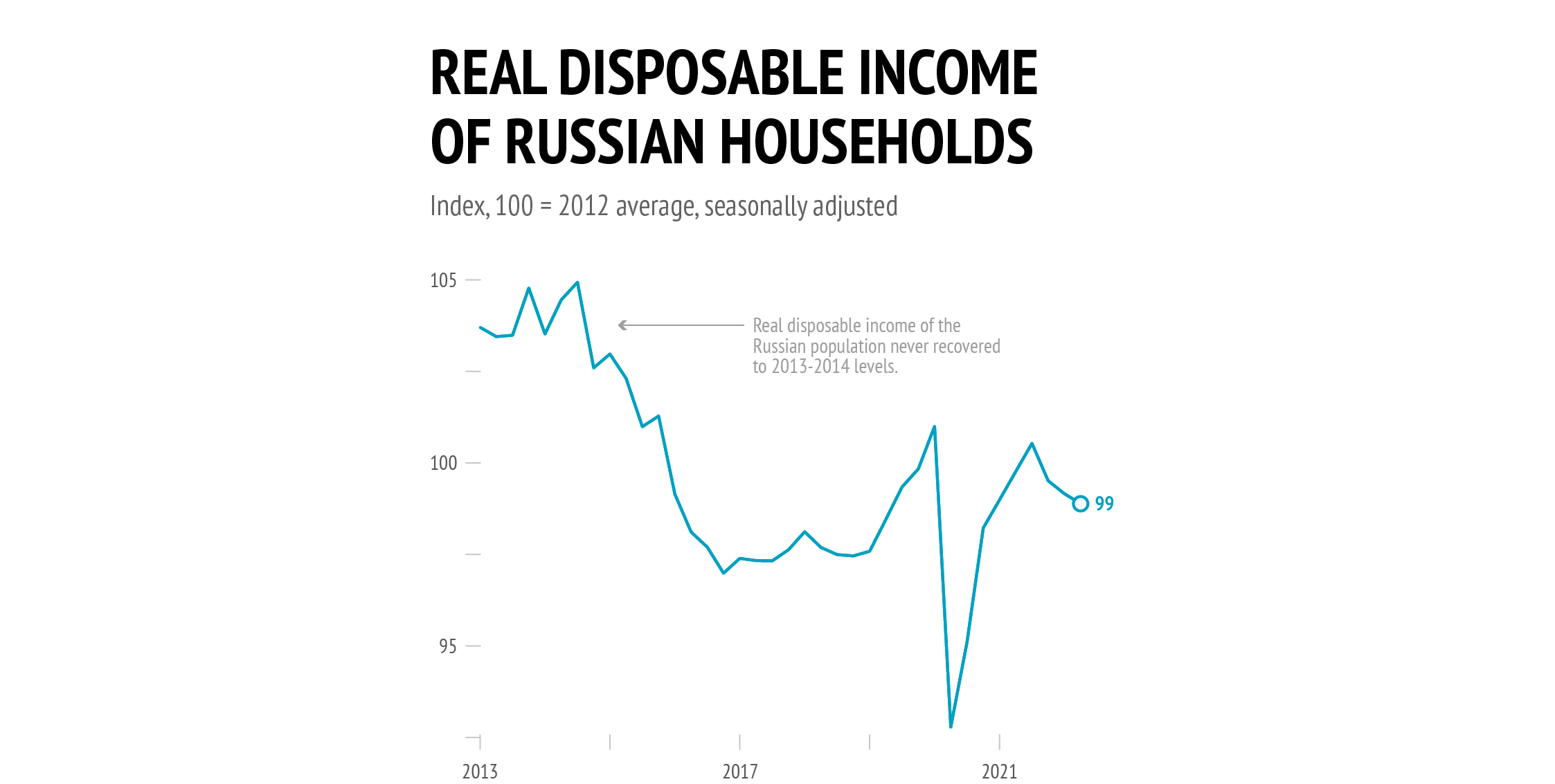

Among the broader population, the urban upper middle class — those who work with international businesses, consume Western goods or travel to Europe — has been the most affected. Real retail spending, an indicator for private consumption, fell by 12.6 % from February to July 2022 (49). For the rest, the symptoms of this economic crisis do not differ much from the previous downturns in 2009, 2014/2015 and 2020. Although factory standstill prevents over 200 000 employees from working, the official unemployment rate remains very low (50). Nevertheless, by temporarily supporting incomes and the most affected economic sectors to avoid a rise in unemployment, the government’s crisis response is designed for a short crisis (51). While the current crisis is taking time to affect the average citizen, it is bound to reduce Russia’s economic potential and living standards permanently. The experience of the 2014 downturn offers a point of comparison. Although the real disposable incomes of the Russian population never went back to 2013 levels because of government efforts to balance the budget despite lower oil prices, the government’s popularity initially did not decline (52). However, years into the crisis, government approval suddenly plummeted after it announced a rise in the pension age, galvanising the economic frustration of the previous years (53). In the long run, the popular discontent caused by the recently announced mobilisation may be exacerbated by the effects of budget cuts triggered by the 2022 sanctions (54).

A delayed impact - but prolonged and severe

Atypically, two different logics combine in the current EU sanctions regime on Russia: the traditional logic aimed at weakening the economy and reducing the revenue available to support the war effort, and a more selective logic targeting the elites in an effort to push them away from supporting the regime. This departs from Brussels’ standard practice, which applies the selective — or targeted — approach in most of its sanctions regimes.

Our analysis shows that economic impacts are taking effect, although political impacts on key elites and the population are not (yet) observable. This is hardly surprising in view of the limited timeframe in which sanctions have been in force. In classical sanctions theory, the political crisis follows the economic downturn, and it takes time for it to be felt. However, translation into political resistance to Kremlin policies encounters a more formidable obstacle: the strengthening of political rivals is largely impeded by a repressive apparatus that threatens dissenting elites and citizenry alike with retribution. The announcement of mobilisation, which has brought the war ‘home’ to the Russian people, has proved a considerably more powerful trigger for popular contestation of the Kremlin’s policies than a moderate decline in prosperity and the prospect of its aggravation.

This does not mean than sanctions have played a negligible role. As the economic effects of sanctions intensify, they will make it more difficult to sustain the war effort and contain the decline in living standards. While sanctions are a slow tool, time works in their favour. Moreover, the effects of sanctions will be lasting and hard to reverse. Restrictions on the supply of technology, which have proved to have powerful ramifications across manufacturing industries, resemble export controls more than a sanctions exercise. Lastly, Brussels’ sanctions are not just about coercing a policy change. Their collective use has allowed the EU to frame a unified stance and demonstrate its commitment to international norms like state sovereignty and the inviolability of borders. The superior importance Brussels attaches to these goals over achieving compliance is reflected in the High Representative’s claim about the inevitability of the sanctions: ‘even if sanctions will not change the Russian trajectory, this does not invalidate their usefulness. Without sanctions, Russia would have its cake and eat it’ (55).

References

1. Wessel, R., Anttila, E., Obenheimer, H. and Ursu, A., ‘The future of EU foreign, security and defence policy: Assessing legal options for improvement’, European Law Journal, Vol. 26, No 5-6, 2021.

2. Helwig, N., Jokela, J. and Portela, C., ‘EU-Sanktionspolitik in geopolitischen Zeiten’, Zeitschrift für Integration, 4, 2020, pp. 278-94.

3. Miadzvetskaya, Y. and Challet, C., ‘Are EU restrictive measures really targeted, temporary and preventive? The case of Belarus’, Europe and the World: a Law Review, Vol. 6, No 1, 2022, pp. 1-20.

4. Portela, C., ‘EU-Sanktionen gegen Russland: Ein Überblick’, Osteuropa, Vol. 71, No 10-12, 2022, pp. 103-113.

5. Council Decision (CFSP) 2022/266 of 23 February 2022 concerning restrictive measures in response to the recognition of the non- government controlled areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts of Ukraine and the ordering of Russian armed forces into those areas (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ TXT/?uri=CELEX:32022D0266).

6. Council Decision 2014/145/CFSP of 17 March 2014 concerning restrictive measures in respect of actions undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine (https:// eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02014D0145-20220721).

7. Council of the EU, ‘Council adopts full suspension of visa facilitation with Russia’, 9 September 2022 (https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/ press-releases/2022/09/09/council-adopts-full-suspension-of-visa- facilitation-with-russia/).

8. Council Decision 2022/1907/CFSP of 6 October 2022 amending Decision 2014/145/CFSP concerning restrictive measures in respect of actions undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:L:2022:259I:FULL&from=EN).

9. van Bergeijk, P., Economic Diplomacy and the Geography of International Trade, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, 2009.

10. Galtung, J., ‘On the effects of international economic sanctions, with examples from the case of Rhodesia’, World Politics, Vol. 19, No 3, 1967, pp.378-416.

11. Kirshner, J., ‘The microfoundations of economic sanctions’, Security Studies, Vol. 6, No 3, 1997, pp. 32-64.

12. Portela, C., ‘Sanctions, conflict and democratic backsliding’, Brief No 6, EUISS, June 2022 (https://www.iss.europa.eu/content/sanctions- conflict-and-democratic-backsliding).

13. Christie, E., ‘The design and impact of Western economic sanctions against Russia’, RUSI Journal, Vol. 161, No 3, 2016.

14. Council Decision 2014/145/CFSP of 17 March 2014 concerning restrictive measures in respect of actions undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine (https://eur-lex. europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32014D0145).

15. Council of the European Union, ‘Council conclusions on the European security situation’, 24 January 2022 (https://www.consilium.europa.eu/ media/53949/st05591-en22.pdf).

16. EU Council, ‘Declaration by the High Representative on behalf of the European Union on the decisions of the Russian Federation further undermining Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity’, 22 February 2022 (https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/ press-releases/2022/02/22/ukraine-declaration-by-the-high-representative-on-behalf-of-the-european-union-on-the-decisions- of-the-russian-federation-further-undermining-ukraine-s- sovereignty-and-territorial-integrity/).

17. Council Decision (CFSP) 2022/329 of 25 February 2022 amending Decision 2014/145/CFSP concerning restrictive measures in respect of actions undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty and independence of Ukraine (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32022D0329).

18. European Commission, ‘Statement by President von der Leyen on further measures to react to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine’, 26 February 2022 (https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ statement_22_1422).

19. European Commission, ‘Statement by President von der Leyen on the fourth package of restrictive measures against Russia’, 11 March 2022 (https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/es/ statement_22_1724).

20. Borrell, J., ‘Beyond sanctions: what future for Russia?’, Working Paper 6/22, Instituto Complutense de Estudios Internacionales, 2022 (https:// www.ucm.es/icei/file/wp0622-1?ver).

21. Elliott, KA., ‘Assessing UN sanctions after the Cold War: new and evolving standards of measurement’, International Journal, Vol. 65, No 1, 2010, pp. 85-97.

22. Doxey, M., ‘International Sanctions: A framework for analysis with special reference to the UN and Southern Africa’, International Organization Vol. 26, No 3, 1972, pp. 527-550.

23. Barber, J., ‘Economic sanctions as a policy instrument’, International Affairs, Vol. 55, No 3, 1979, pp. 367-384.

24. ‘Statement by President von der Leyen on further measures to react to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine’, op. cit. (emphasis added).

25. Ibid.

26. Ibid.

27. Portela, C., Pospieszna, P., Skrzypczyńska, J. and Walentek, D., ‘Consensus against all odds: Explaining the persistence of EU sanctions on Russia’, Journal of European Integration, Vol. 43, No 6, 2021, pp. 683–99.

28. Hufbauer, GC., Schott, JJ. and Elliot, KA., Economic Sanctions Reconsidered: History and current policy, IIE, Washington, D.C., 1980.

29. Central Bank of Russia, Monetary Policy Report, Vol. 39, No 3, 2022, p. 16 (https://www.cbr.ru/Collection/Collection/File/42215/2022_03_ddcp_e. pdf).

30. Connolly, R., Russia’s Response to Sanctions, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2018.

31. Shagina, M., ‘How disastrous would disconnection from SWIFT be for Russia?’, Carnegie Moscow Center, 28 May 2021 (https:// carnegiemoscow.org/commentary/84634).

32. ‘The Central Bank of Russia shifts its reserves away from the dollar’, The Economist, 17 January 2019.

33. Russian senator Andrey Klishas said in May 2022 that import substitution had ‘completely failed’ and produced nothing but ‘bravura reports’ (https://www.rbc.ru/politics/19/05/2022/6285f0c79a7947c127b ab983).

34. Sonnenfeld, J., Tian, S., Sokolowski, F., Wyrebkowski, M. and Kasprowicz, M., ‘Business retreats and sanctions are crippling the Russian economy’, 2022 (https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers. cfm?abstract_id=4167193).

35. According to Eurostat, EU exports to Russia fell from €7.4 billion in February 2022 to €2.9 billion in April 2022.

36. ‘Split reality’, The Economist, 27 August 2022, pp.55-57.

37. Gioe, D. and Styles, W., ‘Vladimir Putin’s Russian World turned upside down’, Armed Forces & Society, pp. 1-14.

38. Central Bank of Russia, ‘Estimate of Key Aggregates of the Balance of Payments of the Russian Federation’, 2022.

39. Simola, H., ‘Trade sanctions and Russian production’, BOFIT Policy Brief, No 4, 2022 (https://helda.helsinki.fi/bof/bitstream/ handle/123456789/18406/bpb2204.pdf?sequence=1).

40. Kluge, J., ‘Mounting pressure on Russia’s government budget’, SWP Research Paper 2019/RP 02, SWP, 2019.

41. Data from the Russian Ministry of Finance (minfin.gov.ru).

42. Kommersant, ‘Rossiya tratit ogromnyye sredstva na podderzhku ekonomiki’, 27 May 2022 (https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/5378720).

43. Data from the budget draft law for 2023 (https://sozd.duma.gov.ru/ bill/201614-8).

44. Data from the Russian Ministry of Finance (minfin.gov.ru) and the Central Bank of Russia (cbr.ru).

45. Tax increases are highly unpopular and have caused political backlash in the past, while printing money would increase inflationary risks.

46. Among them Mikhail Fridman, Oleg Deripaska and the Lukoil Board of Directors.

47. New York Times, ‘Russian tycoon criticized Putin’s war. Retribution was swift’, 1 May 2022 (https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/01/world/europe/ oligarch-putin-oleg-tinkov.html).

48. Farida Rustamova, ‘“They’re carefully enunciating the word clusterf*ck”- How Russian officials and members of parliament really feel about Putin’s decision to send troops to Ukraine’, Faridaily, 6 March 2022 (https://faridaily.substack.com/p/theyre-carefully-enunciating-the).

49. Adjusted for inflation and seasonal effects: from 108 % to 94.4 % of the 2019 level (https://dcenter.hse.ru/macromonitor).

50. Statement by President Putin, (http://kremlin.ru/events/president/ news/69336).

51. Yakovlev, A. ‘Fighting the pandemic and fighting sanctions: Can the Russian economy now benefit from its experience with anti-crisis measures?’, Russia Analytical Digest 285, 2022, pp. 5-6.

52. Frye, T., ‘Economic Sanctions and Public Opinion: Survey Experiments From Russia’, Comparative Economic Studies, Vol. 52 No 7, 2019, pp. 967-994.

53. Kluge, J., ‘Kremlin launches risky pension reform: plan to raise retirement age undermines confidence in Russian leadership’, SWP Comment 2018/C 28, SWP, 2018 (https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/ publication/kremlin-launches-risky-pension-reform).

54. Data from Russian pollster FOM show an unprecedented shift from ‘calm’ to ‘worrying’ mood (https://media.fom.ru/fom-bd/d38no2022. pdf). The pollster Levada also registered a significant decline in approval for President Putin after the announcement of mobilisation (https:// www.levada.ru/indikatory/).

55. ‘Beyond sanctions: what future for Russia?’, op. cit.