You are here

Rebuilding trust

Introduction

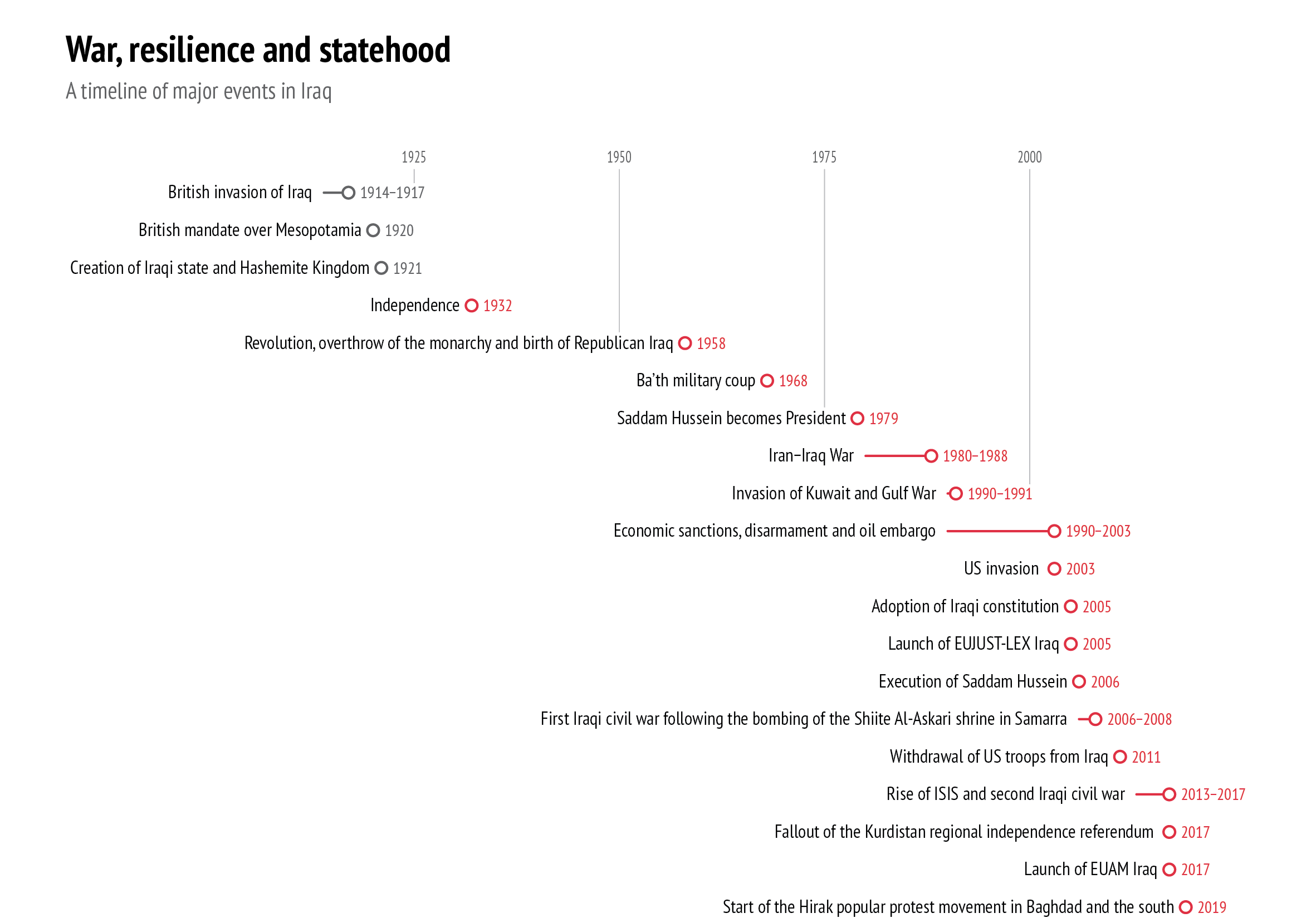

On 19 March 2023, one day before the 20th anniversary of the American invasion of Iraq, Josep Borrell, the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (HR/VP) of the European Union, presided over the third EU-Iraq Cooperation Council in Brussels. With his Iraqi counterpart, Minister of Foreign Affairs Fuad Hussein (1), he discussed developments in Iraq and the EU’s role in relation to regional affairs and security, governance, trade and energy. They both agreed on the need to step up development cooperation. Iraq’s admission as a member state of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) on 9 May enshrined this rapprochement between the two partners.

The era of European disunity, when Member States were split between opponents (mainly France and Germany) and supporters (Britain, Spain, Italy, and Poland among others) of the US-led invasion in Iraq, has long since been forgotten. Nevertheless, this rift delayed the establishment of full relations between the EU and Iraq. It was only in 2005 that the EU established a permanent delegation in Baghdad, followed ten years later by a Liaison Office in Erbil in 2015. In the following years, the bloc gradually regained relevance in Iraq, providing assistance in various areas, ranging from humanitarian aid to security sector reform (SSR), post-conflict stabilisation and economic recovery programmes, among others.

Today the EU is the largest provider of aid to Iraq, on top of the substantial contributions made by Member States. Nevertheless, perceptions in Iraq have been that the EU has no real policy towards the country. This state of affairs compounds the EU’s reputation in the region in general and Iraq in particular, as a ‘payer’ rather than a ‘player’ (2).

This Brief examines EU-Iraq relations, how they have evolved since 2003 and how they can be enhanced. The first section of the Brief explains the importance of Iraq to the EU, while the second critically examines the EU’s presence in Iraq since 2003. The third section provides policy recommendations, stressing the need for the EU to ‘update’ its perception of Iraq, and explores ways for the EU to pursue a more proactive and mutually beneficial partnership with the country.

Why Iraq matters

Iraqi political decision-makers view the EU as a significant economic partner but a weak political actor (3). They often lament the Union’s limited visibility in their country, as they consider that there are many sectors in which a stronger European presence is both essential and mutually advantageous. Even within the EU, some recognise that the EU could do more in Iraq. In the words of a former EU diplomat with experience in Iraq: ‘Brussels is not conscious of Iraq’s full potential’ (4).

In an age of energy insecurity, the EU will gain from helping Iraq to develop its oil and gas sector.

In contrast to the United States, the EU is perceived in Iraq as a ‘benevolent’ player with a well-intentioned agenda, unencumbered by problematic ‘historical baggage’ (5). This overall positive perception means that the EU is able to pursue a more active and multi-faceted diplomacy towards the country. The EU’s more prominent role in Iraq has been facilitated by a confluence of external and internal factors.

Firstly, the United States is ‘downsizing’ its level of political and military engagement in the Middle East and Iraq, in particular, to focus on the rivalry with China in the Indo-Pacific. This dynamic provides a new climate of opportunity for the EU to assume a front-row role in the country. Secondly, the Iraqi polity has undergone tremendous change since 2003 and is at a critical juncture, in quest of an increasing degree of geopolitical autonomy and external support to transition from a war society to a developing economy. The EU has a number of cards to play with its knowledge, expertise and aid.

Furthermore, Iraq is geographically much closer to Europe than to the United States. Any serious deterioration in its stability has immediate repercussions on European states, whether in terms of an influx of refugees and economic migrants or potential terrorist attacks on European soil as seen following the advent of the self-proclaimed Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in 2014.

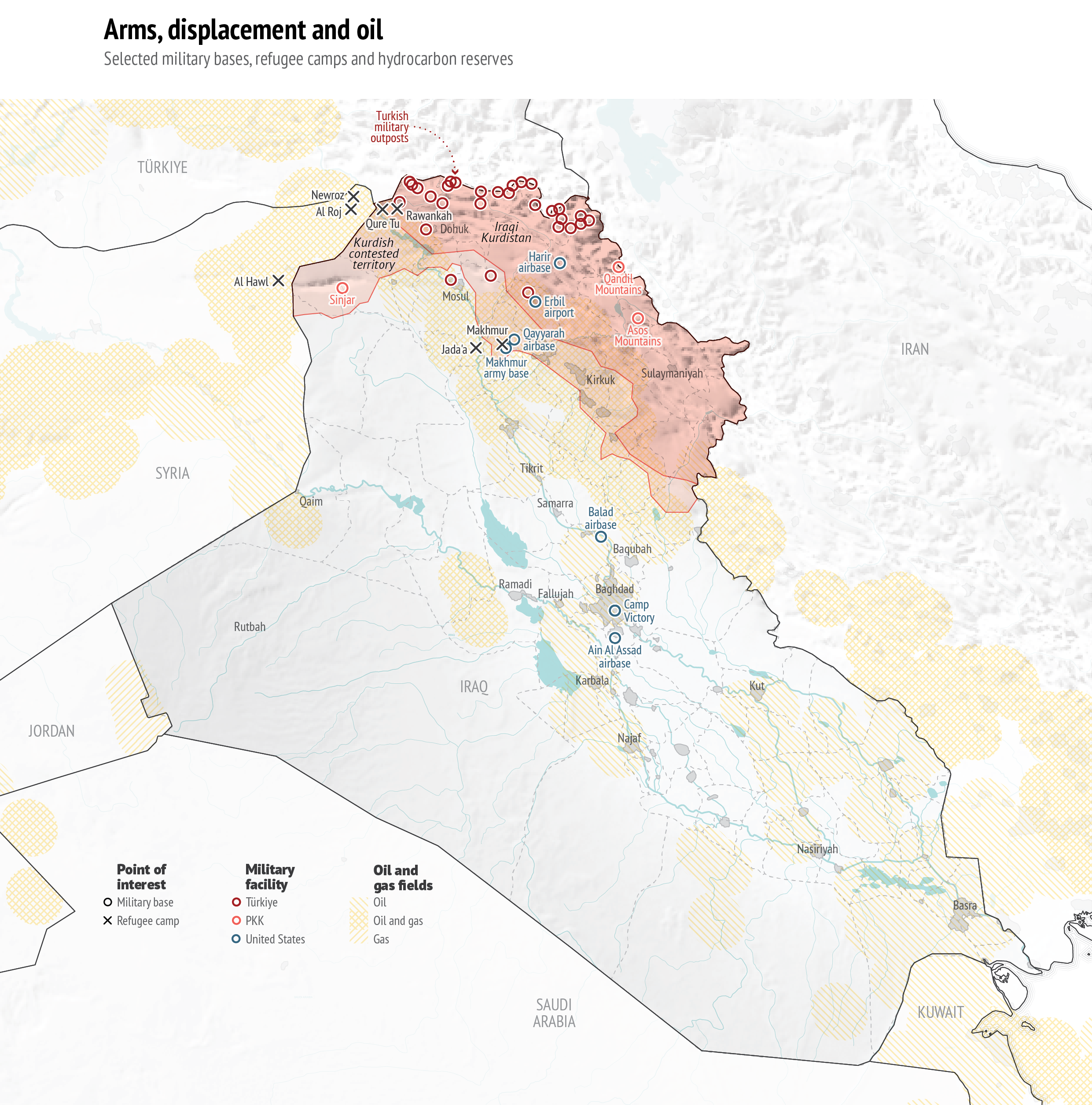

In addition, Iraq lies at the heart of the Middle East not only due to its unique geographical position, bordering several other countries, including the three regional giants, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Türkiye, as well as Syria, Jordan, and Kuwait, but also by virtue of the size of its population, and its historical and cultural importance. As such, what happens in Iraq shapes the regional balance of power and alliances and entails consequences for wider stability. For instance, internal tensions or fissures in Iraq, such as ethno-sectarian strife, have the potential to spill over into other countries in the region. For over more than two decades, Iraq has also been a key battleground in the fight against terrorism and extremist groups like al-Qaeda and ISIS.

Data: ISWN, Middle East Conflict Map, 2023; PRIO, PETRODATA v1.2; RUDAW, 2023; SWP, 2023; European Commission, GISCO, 2023; Natural Earth, 2023

Moreover, Iraq plays a vital role in global energy supplies. It is the second-largest crude oil producer in the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) after Saudi Arabia and has the world’s fifth-largest proven crude oil reserves (145 billion barrels), accounting for 17 % of proven Middle Eastern reserves and 8 % of worldwide reserves (6). Although India and China absorb almost 60 % of Iraq’s total oil exports, Europe is the third destination with 12 % (7). In an age of energy insecurity, the EU will gain from helping Iraq to develop its oil and gas sector. Iraqi oil is becoming increasingly important for the energy security of several European nations (Greece, Italy and Spain) and major oil companies, such as the Italian ENI and French Total Energies which have a substantial stake in the development and upgrading of Iraq’s hydrocarbon industry.

Last but not least, Iraq’s economy has been growing despite years of turmoil and is likely to continue to do so in the years ahead. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), between 2023 and 2028, Iraq’s GDP is projected to increase by 22 % (8). This, combined with rising household income, has created the conditions for a burgeoning consumer market of no less than 43 million people. Indeed, Iraq’s imports have increased from USD 47 billion in 2011 to USD 72 billion in 2019, a figure likely to continue to increase over the next few years, given Iraq’s high rate of demographic growth. The EU could tap into this growing market to expand and diversify its economic and trade relations with Iraq. For now, the EU is Iraq’s fourth trade partner – representing 12 % of Iraq’s total imports in 2020 – lagging behind India, China and Türkiye. In 2020, Iraq accounted for just 0.3 % of the EU’s total trade in goods with the world (9).

The EU's cautious first steps

In December 2005, the EU established a modest presence in Baghdad and early on positioned itself as a major donor to support Iraq’s recovery and reconstruction at a series of international conferences. Shortly after the 2003 invasion, the EU initiated an International Donors’ Conference on Reconstruction in Madrid and repeated this initiative in 2005 (10). In February 2018, in the aftermath of the victory over ISIS, the EU served as co-chair of the Kuwait Summit on Iraqi Reconstruction and pledged a funding commitment of €400 million to help national reconciliation and reconstruction (11). More recently, in December 2022, HR/VP Borrell attended a similar conference to reaffirm European support for Iraq. Altogether, the EU has donated over €1 billion since 2014.

Simultaneously, the EU has put an emphasis on civilian crisis management, especially reforming and strengthening institutions. At the request of the first post-invasion Iraqi government, it launched the European Union Integrated Rule of Law Mission in Iraq (EUJUST LEX-Iraq) which lasted until 2013. This mission aimed at improving Iraq’s criminal justice system through the training of the upper echelons of Iraq’s judiciary, police and prison services. Due to the upsurge in violence in those years, the training took place only in Brussels. At least 7 000 Iraqi officials benefited from the training, but the overall impact was questioned. Executing a rule-of-law mission from abroad against the backdrop of a politicised judiciary and largely corrupt and brutal law enforcement agencies was an exercise of limited scope and value and was considered by many as a ‘waste of resources’ (12). In the case of Iraq, in-situ support would have been better, coupled with help to fight or at least curb corruption.

In 2017, at the request of Baghdad, the European Council launched the EU Advisory Mission in Iraq (EUAM Iraq), a civilian CSDP mission (13). Extended until 2022, EUAM Iraq advised officials from the Office of the National Security and the Ministry of Interior on security sector reform. Again, the effectiveness of this mission has been questioned since several Iraqi security officials in the programme belonged to the multiple armed militias which had infiltrated the state. Additionally, the security threats resulting from sectarian policies and subsequent discrimination against the Sunni population, particularly under the rule of former prime minister Nouri al-Maliki (2006-2014), were not properly addressed.

State capacity-building efforts also included electoral assistance (notably in the context of the March 2010 legislative elections) (14) and, in 2012, the signing of a Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA) establishing a legal framework for enhancing ties and cooperation in various areas such as political issues, counterterrorism, trade, human rights, health, education and the environment.

Although the EU did not play a prominent military role in the fight against ISIS, it nonetheless participated as a non-military partner in the US-led Global Coalition Against Terrorism. Together with Syria, Iraq was incorporated in the same European strategy to defeat ISIS on all fronts, which consisted of providing support and training to the Iraqi Counter-Terrorism Forces and federal police forces as well as Iraqi Peshmergas and Syrian Kurdish paramilitary and intelligence forces.

At the same time, the EU also stepped up its humanitarian aid. The European Commission’s Humanitarian Office (ECHO) was established in Erbil in 2014 and implemented an Iraq-wide humanitarian aid programme over the next two years that provided assistance to 3.2 million internally displaced Iraqis. Through projects funded by the Instrument Contributing to Peace and Stability (IcSP), the EU has also engaged in several reconstruction and rehabilitation activities since 2015, including national reconciliation and stabilisation efforts (provision of security and basic services, rehabilitation of infrastructure), removal of explosive hazards in areas liberated from ISIS occupation, counterterrorism training, border control and protection of cultural heritage (15).

Some projects were successful such as the Funding Facility for Stabilisation (FFS) established by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) with EU funds. The EU’s contribution to the FFS was marginal: out of the €1.5 billion spent, the United States donated €434 million, Germany alone €382 million while the EU’s contribution was limited to €70 million. Therefore the success of the FFS does not owe much to the EU (16). Other initiatives, such as ‘Supporting Iraq National Reconciliation’ (2015– 2017), a campaign focused on the (re-)integration of Sunni ‘opposition’ elements into national politics, accomplished little according to several local political figures (17).

Since 2018, cognisant of the deficiencies of its approach in Iraq, the EU has sought to adjust its interventions in the country, balancing immediate humanitarian assistance needs with longer-term goals for development and peace. For instance, the EU has commissioned international mediation groups to develop and manage projects fostering the resolution of grievances between local communities and the central government, especially in the liberated governorates (Nineveh, Salah ad-Din, and Anbar) west and northwest of Baghdad. Tackling the poisonous legacy of ISIS and the chaos and multiple conflicts spawned by its rule was viewed as a priority. This is especially important given the low priority given to such endeavours by the Iraqi ruling elites. The effort seems to have created the groundwork for communication between minorities (Yazidi, Christians, etc.) and the majority Muslim population, especially in Nineveh.

Taking a step back to move forward

As seen above, EU involvement in Iraq since 2005 has oscillated between state-building, humanitarian aid and stabilisation operations. Yet, the EU remains politically and economically invisible or marginal in Iraq. This stems from the fact the EU has largely been content to delegate tasks to international partners, mainly the UN mission in Iraq (UNAMI) and other UN agencies (UNDP, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees - UNHCR, and the International Organization for Migration - IOM). UNAMI has been taking the lead in monitoring and providing assistance for governance issues. For its part, NATO has been the major institution coordinating military and security cooperation. Last but not least, individual EU Member States act separately and often in competition with one another. Some Member States prioritise realpolitik (i.e., economic interests and security cooperation) to advance the political and economic role they aim to play in the region, while others pursue a more subtle foreign policy, emphasising cultural and technological collaboration (18).

It is important to ensure that equidistance is reestablished between Baghdad and Erbil.

In Iraq, the EU needs to start with a realistic assessment of past and ongoing political dynamics. The nomination of Nouri al-Maliki as prime minister in 2006, which failed to raise any alarm signals in Brussels, is a case in point. Moreover, the EU continued to train Iraqi legal experts under EUJUST-LEX even while the Iraqi state apparatus was being heavily politicised and infiltrated by clientelist networks and armed militias. Notwithstanding the trend towards more repression targeting civil society activists and organisations, the EU did not attach any conditions to its cooperation, even when the massive popular protests that broke out in the country in 2019 resulted in the killing and injury of hundreds of protesters (19).

For EU-Iraq relations to move forward, the EU needs to recalibrate its vision of Iraq, reassess the country’s needs and change the focus of its priorities to help the country more effectively. In particular, it is important to ensure that equidistance is reestablished between Baghdad and Erbil.

'Seeing Iraq for what it is'

The EU needs to revise its perception of Iraq and develop a strategy based on a realistic approach to the country – ‘seeing Iraq for what it is and not for what it would like it to be’ (20). In particular, it is imperative to ensure that the EU develops a strategy based on the reality of the situation prevailing in Iraq today rather than on a utopian vision of what it should ideally be. The historical sequence opened by the 2003 war is over. Iraq’s political system is relatively stabilised. While its main actors have moved away from sectarian politics and rivalries where most influential politicians and ministers command or belong to armed militias and are strongly committed to upholding the status quo, its opponents have neither the will nor the capacity to engage in a violent confrontation. Although not fully eradicated, terrorism is on the decline, in no small part because Iraqis are weary of bloodshed and violence.

On the political level, Iraq is neither an outright authoritarian regime nor a liberal democracy, but its citizens enjoy more freedom than some of their counterparts in other Arab states. They live in a semi-pluralistic society but under a watchful and repressive regime.

Iraq is not a theocracy, but the highest Shiite authority Ayatollah Al-Sistani is rarely criticised publicly, and society remains very conservative, attached to traditional religious and cultural beliefs. The 2020 controversy over the EU’s diplomatic missions in Baghdad raising the LGBTQ+ flag to mark International Day Against Homophobia is a case in point. Iraqi politicians and religious authorities unanimously condemned the EU mission for offending the country’s ‘values and social norms’ (21). A large majority of Iraqis believe that EU countries are Islamophobic and that they promote an LGBTQ+ agenda. The assault on the Swedish embassy in Baghdad at the end of June, after a man burned a copy of the Quran outside a mosque in Stockholm, is another example. Gathered in front of the Swedish embassy, several hundred Iraqis burnt the LGBTQ+ flag in retaliation for the burning of the Quran (22).

Since 2006, Islamist political actors have dominated successive Iraqi governments, but none have sought to break the consensus (tawaffuq)-based political system and its corollary, the allocation of power and resources according to ethnic and sectarian quotas. Nor have they sought to impose an Islamist regime. Iraqi society is undergoing a silent process of secularisation amid a growing rejection of sectarian discourse and practices. Western governments’ characterisation of the country’s political landscape in terms of secular versus religious political actors has little relevance in today’s Iraq. Leading Shiite Islamist actors, including Qais al-Khazali, leader of the Asaeb Ahl Al-Haqq (AAH) militia and a close ally of Tehran, stated recently that entities such as the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) or the Lebanese Hezbollah cannot be replicated in an ethnically and religiously diverse country such as Iraq (23).

Irrespective of their composition and degree of closeness to Tehran, Iraqi governments remain willing to cooperate with Western countries, including the United States, which maintains military bases and instructors in the country. As a prominent Shia islamist political leader known for his good relations with Western countries and the Gulf noted in an interview: ‘no Iraqi political formation, not even Sunni, is hostile to Iranians with whom we form a family. The whole question is whether Iran is our father, our big brother or if we are just cousins? Iraqi Shiism will take many years to formulate an identity distinct from Iran but it will end up doing so’ (24).

While the Islamic Republic of Iran is very influential and maintains an active presence in Iraq, notably through multiple proxies, and religious and economic networks, it is also increasingly contested due to a rise in Iraqi nationalist sentiment and a stronger desire for state sovereignty and territorial integrity. Besides, despite verbal escalation and armed skirmishes on Iraqi soil, the United States and Iran have demonstrated their shared commitment to preventing Iraq’s destabilisation. As such, Iraq should not be punished for being Iran’s neighbour. Europe should not limit its bilateral exchanges with Iraq for fear of indirectly favouring Iranian interests (given Tehran’s efforts to circumvent international sanctions and pursue its nuclear ambitions).

Reassessing aid effectiveness

First, Iraq is an oil-rich country which currently does not need humanitarian aid. The primary humanitarian concern should be detention camps such as the al-Hol camp in north-eastern Syria and the Jad’a camp south of Mosul where Iraqis suspected of belonging to ISIS are held. Unrepatriated Iraqi nationals detained in Syria or those confined in the Jad’a rehabilitation camp potentially represent an ongoing security threat. Iraqis comprise more than half of al-Hol camp’s population in Rojava’s Hasaka governorate (25). The majority of the camp’s over 50 000 inhabitants are the spouses and children of ISIS combatants. In the past year, Iraq has repatriated over 700 families from al-Hol, with the majority undergoing rehabilitation in Iraq. Yet, at the current pace of return, it will take years to empty the camp. It is widely believed that the appalling living conditions of the detainees and their strong ties to the residual ISIS cells on the run entail the risk of producing a new wave of radicalisation (26).

Second, the EU’s focus on internally displaced persons (IDPs) needs to be reassessed. Figures provided by international aid agencies still put the number of IDPs at more than one million people six years after ISIS was defeated while Iraqi officials from the Ministry of Migration and Displacement admit that the majority of them have settled in urban areas for purely economic reasons (27). The EU needs to acknowledge that ‘residual’ displacement is no longer related to military operations, but rather related to regional disparities across the territory and imbalances in the distribution of public services (health, education, infrastructure, etc.) and as a consequence lack of economic opportunities. Besides, the IDP issue is connected on the one hand to the conflict between the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and Baghdad, notably the disputed internal boundaries that are claimed by both parties and, on the other hand, to external conflicts such as Türkiye’s war against the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) in Sinjar. Hence, resolving the IDP issue will require engagement in political mediation efforts.

Third, the focus on the security sector needs to be reconsidered. Statistics are ambiguous and imprecise but if we take into consideration the complex and hybrid architecture of the Iraqi security apparatuses between the militias (380 000), the Pershmarga (200 000) and the regular army (300 000), their number approximately equates to no less than 800,000 (28). By regional standards, the Iraqi counter-terrorism forces (ICT) are among the best trained and most seasoned, and there is limited need for the EU to help in this regard. In addition, calling for the dismantling of the Hashd Shaabi (Popular Mobilisation Forces or PMF), predominantly Shiite and including Iran-backed groups, is neither realistic nor desirable as it entails the risk of political destabilisation leading to a cycle of intra-Shiite violence. Not to mention the considerable ideological and economic weight that these hybrid forces (half-regular, half-irregular and funded by the state) carry. The PMF provide tens of thousands of jobs to young people who would otherwise run the risk of being absorbed by a mafia economy, drug trafficking or crime. Therefore, SSR cannot move forward without a comprehensive overhaul of the Iraqi political system, a prospect that seems unlikely to materialise in the short term (29).

Furthermore, the EU could prioritise aid to tackle the structural weaknesses of the Iraqi economy. The poor quality of political and economic governance in the country has pushed young Iraqis, including Kurds, into unemployment and migration. With the second-highest fertility rate in the MENA region (30), a private sector that is either corrupt or non-existent, and a rentier economy, there is a need for deep structural reform. Employment in the public sector has become part of the social contract between the government and society, and the government has expanded the bureaucracy at the expense of economic diversification and private sector support. There are eight million Iraqis who receive salaries, pensions or other social benefits from the state (31). Given Iraq’s rapid population growth, this short-sighted and inefficient economic model is untenable and endangers the country’s future prosperity.

Instead of aid, Iraq needs a strategic vision for development. Iraq has been cut off from the rest of the world for decades, and while the progress made since 2003 is to be acknowledged, the country lags behind its neighbours in various domains such as innovative technologies, banking, insurance, legislation, cybersecurity, infrastructure and energy supply, resource management, education and cultural exchanges.

Data: OPCW, 2017

Finally, there is a field where the EU has a lot to offer in the light of Iraq’s growing environmental vulnerability. The country has been ranked the fifth-most exposed country to climate change, with elevated temperatures, declining rainfall, increasing droughts and water scarcity, frequent sand and dust storms, and flooding. Furthermore, anarchic urbanisation and ageing water infrastructures, especially irrigation systems, are increasing the demand for additional water supplies. In Iraq, climate migration is already a reality. Water scarcity and pollution, as well as high salinity, are causing a continuous rural exodus as people move to urban centres in search of work (32). The EU could promote a long-term ‘green’ diplomacy approach focusing on mitigating the adverse consequences of climate change and developing clean energy. One concrete first step could be involving Iraq in the EU-GCC Clean Energy Technology Network (CENII), established in 2010 and launched in 2015 (33). This would foster an energy partnership and be beneficial for both parties.

Acting as an honest broker between Baghdad and Erbil

The EU needs a comprehensive political framework and strategy aimed at enabling real rather than just cosmetic reforms in both Baghdad and Erbil. For that purpose, the EU should try to rebalance its relations with the Arab and Kurd communities in Iraq. A weak, unstable and non-democratic Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) is in no-one’s interest. Unlike Baghdad, the KRG has powerful lobbies in Brussels and several European capitals. Moreover, Iraq’s successive foreign affairs ministers have all been Kurds.

The EU could help also in constitutional reform, and settling disputes (i.e., over oil and gas exports, or contested internal boundaries) between Baghdad and the KRG. Iraqi Kurdistan also has the potential to turn into a regional battleground given Turkish and Iranian cross-border military operations against their respective Kurdish opposition groups, which have sought refuge across northern Iraq (the PKK in Mount Sinjar and Qandil; Iranian Kurds in and around Sulaymaniyah).

Conclusion

Clearly, the EU needs to find a compromise between its normative postures and fostering pragmatic imperatives of economic development and political stability in Iraq.

While Iraq is struggling with various issues, the country possesses a number of assets, as previously mentioned (i.e., significant human capital, an active and diverse civil society, well-trained security forces, abundant natural resources and a unique geostrategic location). The EU could capitalise on and tap into these assets to help the country develop and prosper. However, this can be done only if the EU’s institutions, starting with the European External Action Service (EEAS), readjust their vision of the country and come to terms with the reality of Iraq as it is today. Only then will the EU be able to identify the important areas where it can make a difference, instead of tackling overwhelming and multi-layered difficulties that cannot be solved. A reassessment of Iraq’s needs and a focus on how the EU can make the best use of the tools at its disposal to help Iraq achieve a better future are mandatory to move the EU-Iraq relationship to the next level.

References

* The authors would like to thank Caspar Hobhouse, EUISS MENA trainee, for his research assistance.

1. European Council of the European Union (Newsroom), ‘EU-Iraq Cooperation Council - March 2023’, 19 March 2023 (https://newsroom. consilium.europa.eu/events/20230319-eu-iraq-cooperation-council- march-2023).

2. Former Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon originally coined this expression, and it was subsequently used by a number of scholars and analysts. See: bin Talal, E.H., ‘From payer to player in the Middle East’, Project Syndicate, October 2007 (https://www.project-syndicate.org/ commentary/from-payer-to-player-in-the-middle-east).

3. Fawcett, L., ‘The Iraq War 20 years on: towards a new regional architecture’, International Affairs, Vol. 99, No 2, March 2023 (https://doi. org/10.1093/ia/iiad002); see also: Wirya, K., Ala’Aldeen, D. and Palani, K., ‘Perceptions of EU crisis response in Iraq’, MERI and EUNPACK, 2017 (http://www.meri-k.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/NUPI-Report.pdf).

4. Interview conducted in Baghdad by Loulouwa Al Rachid in 2021.

5. These perceptions are based on several fieldwork visits and interviews with local citizens and politicians conducted by one of the authors (Loulouwa Al Rachid) across Iraq since October 2022.

6. Energy Information Administration (EIA), ‘Iraq – 2021 primary energy data in quadrillion Btu’, 2021 (https://www.eia.gov/international/ overview/country/irq).

7. OEC, ‘Crude petroleum in Iraq’ (https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral- product/crude-petroleum/reporter/irq#:~:text=In%202021%2C%20 Iraq%20exported%20%2472B%20in%20Crude%20Petroleum.,Arab%20 Emirates%20(%249.94k).

8. Statista, ‘Iraq: Gross domestic product (GDP) in current prices from 2008 to 2028’ (https://www.statista.com/statistics/326979/gross-domestic- product-gdp-in-iraq/).

9. European Commission, ‘Iraq: EU trade relations with Iraq – Facts, figures and latest developments’ (https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade- relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/iraq_en).

10. Reliefweb, ‘Conclusion of Madrid Conference on Iraq’, 23-24 October 2003 (https://reliefweb.int/report/iraq/conclusion-madrid-conference- iraq-23-24-oct-2003).

11. ‘Kuwait summit: $30 billion to rebuild Iraq’, Deutsche Welle, 14 February 2018 (https://www.dw.com/en/kuwait-summit-promises-30-billion- in-iraq-reconstruction-aid/a-42586658).

12. Several people in the political establishment but also in the civil society sector used this expression when talking about the EU.

13. European Union Advisory Mission in Iraq: https://www.euam-iraq.eu/ en/about

14. See van Veen, E., Di Pietrantonio, A., Pellise, N., Ezzeddine, P. N, ‘CRU Report’, Clingendael, February 2021 (https://www.clingendael.org/sites/ default/files/2021-02/eu-relevance-in-the-syrian-and-iraqi-civil-wars. pdf).

15. European External Action Service (EEAS), ‘The European Union continues to support explosive hazard management in liberated areas of Iraq’, 19 December 2018 (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/node/55715_en).

16. This project concentrated on rehabilitating public facilities (particularly schools and hospitals), electricity networks and infrastructure, and creating livelihood opportunities through cash-for-work programmes.

17. Interviews with local politicians conducted by one of the authors in summer 2022.

18. It should be mentioned that Germany falls within this category. The country is seen favourably, and former German chancellor Angela Merkel was very popular in Iraq. She became known as al-khaleh Merkel (Auntie Merkel), and several songs about her have become online sensations. (See: https://shorturl.at/JRXZ8 or https://shorturl.at/oDEVX). Merkel gained popularity for her open-door policy towards migrants, especially Syrians. As a result, Berlin became known as the European capital of Arab culture and a favoured venue for the diaspora and communities of the Middle East. Additionally, a German court used the concept of universal jurisdiction to hand down the first sentence on the crime of genocide perpetrated against the Yazidis in November 2021.

19. Human Rights Watch, ‘Iraq state appears complicit’, 16 December 2019 (https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/12/16/iraq-state-appears-complicit- massacre-protesters).

20. An Iraqi political leader explained this in an interview with Loulouwa Al Rachid in Baghdad in 2022.

21. ‘EU mission slammed for displaying LGBTQ flag in Iraq’, Al Bawaba, 18 May 2020 (https://www.albawaba.com/editors-choice/eu-mission- slammed-displaying-lgbtq-flag-iraq-1357542).

22. ‘Iraq protesters breach Sweden’s embassy over Qur’an burning’, The Guardian, 29 June 2023 (https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/ jun/29/iraq-protesters-breach-swedens-embassy-over-quran-burning).

23. MCD, ‘Interview with Qais Khazali [in Arabic]’, 7 April 2023 (www.mc-doualiya.com/-قيس-الخزعلي-قدر-العراق-أن-يكون-دولة-ونحن-مقتنعون-بالعمل-20230407برامج/مقابلة/من-داخل-الدولة-وتقوية-مؤسساتها).

24. Interview in Baghdad, October 2022.

25. Rudaw, ‘Iraq to repatriate over 150 people from al-Hol camp’, 29 December 2022 (https://shorturl.at/TU456).

26. Rudaw, ‘Iraq praises rehabilitation of nationals from al-Hol camp’, 4 May 2023 (https://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/iraq/04052023).

27. Interviews with Iraqi officials, Baghdad, March-June 2023.

28. Aziz, S. and van Veen, E., ‘A state with four armies: How to deal with the case of Iraq’, War on the Rocks, 11 November 2019 (https://warontherocks.com/2019/11/a-state-with-four-armies-how-to-deal-with-the-case-of-iraq/).

29. Al-Sheikh Hussein, S., ‘Iraq’s security sector: Twenty years of dashed hopes’, Chatham House, March 2023 (https://www.chathamhouse. org/2023/03/iraq-20-years-insider-reflections-war-and-its- aftermath/iraqs-security-sector-twenty-years?utm_source=twitter. com&utm_medium=organic-social&utm_campaign=menap&utm_ content=iraq-20).

30. Statista, ‘Female fertility rate across MENA by country, 2019’, February 2022 (https://www.statista.com/statistics/945008/mena-rate-of- female-fertility-by-country/).

31. Arab News, ‘World’s fastest population growth demands new economic order in Iraq’ 28 June 2021 (https://www.arabnews.com/node/1884591/ business-economy).

32. United Nations Iraq, ‘Migration, environment, and climate change in Iraq’, 11 August 2022 (https://iraq.un.org/en/194355-migration- environment-and-climate-change-iraq). See also, DTM, ‘Drivers of climate-induced displacement in Iraq: Climate vulnerability assessment key findings’, April 2023 (https://iraqdtm.iom.int/files/ Climate/202353458739_DTM_Climate_key_findings_en_v11.pdf).

33. EU GCC Clean Energy Technology Network, ‘Fostering Clean Energy Partnerships’ (https://www.eugcc-cleanergy.net/sites/default/files/ network_new_brochure_-_one_pager_v2.pdf).