On 1 November 2022, leaders and officials from the Arab world met in the Algerian capital for the 31st edition of the Arab League summit, after a three-year hiatus due to the Covid-19 pandemic. At the meeting, branded as the ‘summit of reunion’, Arab leaders talked about the Palestinian cause, the instability of the region, food security and the future of joint Arab action.

For Arab leaders, discussing how to strengthen joint Arab action is challenging because each Arab country has its own agenda. There are internal dissensions within the League of Arab States (LAS) over several issues (including Libya, Yemen, Lebanon and Palestine) and over the reintegration of Syria into the League after its suspension in 2011. Furthermore, the League is divided between pro-Russian and pro-US/ Israeli sympathies, even if many state members claim to be neutral. Since the previous summit in Tunisia in 2019, several countries of the 22-member League, which has for decades represented a platform in support of the Palestinian cause, have taken steps to normalise relations with Israel. The first were the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Bahrain which concluded an agreement brokered by the United States in September 2020, known as the ‘Abraham Accords’. In August 2021, after years of informal ties, Morocco also agreed to normalise relations with Israel.

Between the states that have normalised relations with Israel and those that have so far declined to do so, there are sharp differences of opinion, as is the case between Morocco and Algeria, which remains an ardent supporter of the Palestinians. Before the summit, Algeria negotiated a reconciliation agreement between 14 Palestinian factions, including Hamas, Fatah, Islamic Jihad, and various others.

For Algiers, hosting the summit offered an opportunity to return to the regional arena after an absence of two decades. However, for the LAS, the summit did not accomplish anything significant.

The inability of the LAS to act or to solve regional problems and speak with one voice is due to several factors related to its member states (low human development and government effectiveness indices), regional characteristics (power distribution in the region) and above all, organisational aspects. The latter include the League’s unanimity-based decision-making procedure and the weakness of its institutional mechanisms. This Brief first provides an overview of the shortcomings of the LAS, before going on to analyse how Algeria leveraged the recent summit to its advantage. It concludes by indicating some ways in which the EU could engage more closely and constructively with the LAS.

An organisation designed to fail?

The Arab League was established in 1945 by Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia and Syria. The League was founded in response to concerns about post-war colonial partitions of territory and the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. The Charter established the League’s headquarters in Cairo, created a permanent General Secretariat and stipulated that sessions would be held every two years or at the request of two members in exceptional circumstances.

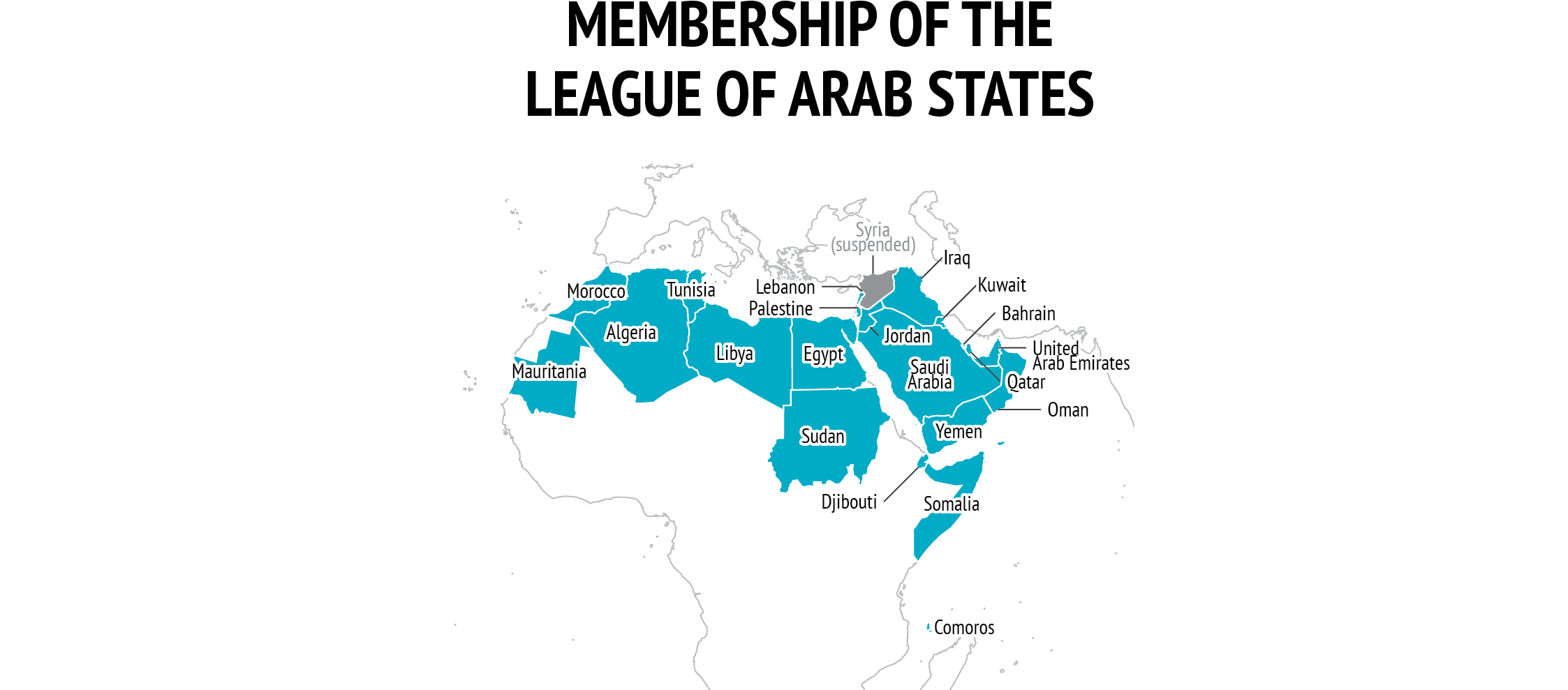

The LAS, composed of 22 Arab countries, is the only institutional framework that spans the entire MENA region. In comparison, the Gulf Council of Cooperation (GCC), the Arab Maghreb Union (UMA), and the Arab Cooperation Council (ACC) are sub-regional forums. As a result, the LAS appears as a natural regional interlocutor. However, due largely to organisational deficits and shortcomings the League has frequently proved unable to tackle regional problems decisively and act in unison.

Data: European Commission, GISCO, 2022

The LAS has a mandate to mediate disputes (Art. 5) and aggression (Art. 6) (1). While article 5 of the Charter prohibits the use of force between members and allows the Council to take arbitration and mediation decisions in regional disputes with a majority vote, article 6 adds that in the event of ‘aggression’, the Council ‘shall by unanimous decision determine the measures’ deemed necessary to respond to such acts. Because the text does not provide a clear definition of ‘aggression’, all regional disputes and conflicts since the League’s inception have, with a few minor exceptions, been portrayed by member states and approached by the League as ‘aggressions’, with each following resolution being subject to a lengthy and complex consensus-building process. Between 1946 and 1977, the Arab League’s average weighted success rate lagged behind that of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), with the League’s success rate registering 12 % against 19 % for the OAU. Both scores however, were higher than the 9 % achieved by the UN (2).

The Charter stipulates that the Arab League was also established to ensure ‘respect for the independence and sovereignty’ of Arab states. This emphasis on national sovereignty restricts its capacity for collective action. The League also lacks a mechanism to enforce members’ compliance with its resolutions. The Charter states that decisions reached by a majority ‘shall bind only those that accept them.’ In other words, only members who voted in favour of decisions can impose them. This implies that each state possesses a quasi-veto authority (3). Therefore, when operations are undertaken under the auspices of the League, they are mostly carried out by a small group of states. Due to member states’ competing interests, casting a majority vote is an extremely difficult task, and for this reason, the LAS’s implementation record has been rather poor. By the 1980s, the LAS had passed more than 4 000 resolutions, of which 80 % were never implemented (4).

Due to its overemphasis on sovereignty, inherent structural weaknesses, and issues with decision-making and enforcement processes, the LAS has been both unable and reluctant to intervene in internal conflicts, even when these have escalated into sub-regional conflicts with the involvement of neighbouring states. There has been a consistent tendency towards non-intervention in the LAS due to internal vetoes as the majority of Arab League members invoke the uti possidetis principle and the inviolability of their borders (5). The League’s track record in resolving civil wars is also disappointing as it has only served as a mediator in 5 of the 22 major civil conflicts in the MENA since 1945 (6).

The League has frequently internalised its role and status as a secondary player when significant power and political interests are at stake. The wars in Libya, Syria and Yemen are all cases that demonstrate how the League has little to no influence when it comes to conflict resolution in the region. In Libya, the LAS showed some tenacity in its diplomatic initiatives and questioned the viability of adopting new measures like creating a regional peacekeeping force. The League’s state members agreed to suspend Libya in February 2011 and established a no-fly zone, yet the LAS failed to find a solution of its own to the Libyan case which continues to pose a threat to security in the region. Also, its members’ so-called ‘unity’ did not last for long, as divisions appeared between those who support the Government of National Accord (GNA) and those who support General Khalifa Haftar’s forces. LAS member states continue to show disunity over the Libyan issue. Recently, on 7 November 2022, Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry left the 158th ordinary session of the Arab League over its chairing by Libyan foreign minister Najla al-Mangoush, as Cairo does not support the Tripoli-based GNA (7).

Nonetheless, it is worth mentioning that since its inception the League has frequently intervened in minor conflicts and was successful in promoting at least a partial settlement in 40 % (8 out of 20) of the recorded boundary wars and political crises in the region. From 1945 to 2008, the LAS made attempts to mediate 19 out of 56 regional conflicts. However, the few achievements of the LAS have not turned it into an active and influential regional actor. It is seen by some as a ‘forum of collective legitimisation’ for leaders who remain oblivious to the realities of their citizens’ lives (8).

A summit leveraged for political effect

Algeria is pursuing more assertive diplomacy as it feels less vulnerable on the domestic front and stronger on international events is part of this new strategy to boost Algeria’s influence in the Mediterranean region. Prior to the LAS summit in June 2022, Algeria had also hosted the 19th edition of the Mediterranean Games for the first time in 47 years, with a sumptuous opening ceremony, welcoming 3 000 athletes from 26 countries of the Mediterranean region (9). The LAS summit was the culmination of its diplomatic charm offensive.

With rumours circulating about the summit being postponed for a second time and some Arab leaders not attending, Algiers made huge efforts to promote the LAS summit. Ahead of the summit, the regime sent one of its most experienced and skilled diplomats, a former ambassador and a great connoisseur of the African continent, Minister of Foreign Affairs Ramtane Lamamra, to personally hand invitations to several Arab leaders (10). Eventually, with the exception of Syria, all Arab states, and United Nations (UN) Secretary-General António Guterres, attended. Two-thirds of Arab leaders attended, while five countries sent lower-level delegations (11).

Lamamra chaired multiple bilateral meetings during the summit with his counterparts from various countries. The minister emphasised that these meetings were ‘very fruitful and constructive’, adding that the dialogues took place in a ‘fraternal and positive’ atmosphere (12). In addition, the Algerian press gave an enthusiastic account of the summit and unanimously quoted the president, Abdelmajid Tebboune, expressing Algeria’s pride and honour in hosting the event.

The LAS summit has provided an opportunity for Algeria to re-establish itself in the regional arena. During the two last mandates of former president Abdelaziz Bouteflika, the country’s diplomacy stagnated. Furthermore, during the previous LAS Summit in 2019, the Algerian regime was struggling with internal problems due to the rise of the mass protest movement, the Hirak, which took the regime off guard. Since then, Bouteflika was ousted, Tebboune was elected and the regime took advantage of the Covid-19 confinement measures to stifle the Hirak (13).

On the international level, the conflict in Ukraine presents Algeria, like many other gas suppliers in the region, with various lucrative energy-related opportunities. A long-time energy exporter to Europe, Algeria has been courted by a number of European countries, such as France, Spain, Portugal, Slovenia and Italy, to increase its gas supplies. This helps the government generate more revenue and to break Algeria’s isolation from the West while keeping channels open to Russia, China and Iran, thus preserving the country’s neutral status and allowing it to carefully avoid being drawn into any single orbit of influence.

Now, the country is readjusting its foreign policy and stepping up its diplomatic efforts within the Arab world and Africa. The summit provided the country with a platform to assert its renewed international confidence and activism. More recently, Algeria submitted an official application to join the BRICS economic bloc of emerging markets, which currently comprises Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. Also, in September, it launched a bid for a non-permanent seat at the United Nations Security Council for the term 2024-2025.

Conclusion

The LAS has lost credibility in recent decades due to the weakness of its institutional mechanisms,and its failure to translate the lofty statements of its leaders into action. The inability to take a united stance on the Palestinian issue, when several Arab leaders decided to normalise relations with Israel, is probably its most profound failure, especially given that an overwhelming majority of 88 % of Arab citizens disapprove of their governments’ recognition of Israel, and only 6 % accept a formal diplomatic recognition (14). Also, the LAS’s credibility is stretched because while it insists on sovereignty and non-aggression, it turns a blind eye to many Arab countries intervening in the domestic affairs of other neighbours, often fuelling more conflicts and confrontations such as in Yemen, Syria, Libya and Iraq.

While the LAS has benefited from its institutional relationship with the EU since 2015, it is perhaps time for it to engage more closely with a partner that has evolved from being simply an instrument for economic cooperation into a coherent political actor and a guardian of peace and security.

Regional economic integration as a driving force for peace could be the first step for the LAS, and the EU offers the first and most successful example of this function. MENA has one of the lowest levels of regional economic integration in the world and lags behind other middle and high-income regional blocs (15). In 2019, while trade between GCC countries stood at 11%, trade between the countries of the Maghreb was just 2.8%, compared to 57.4 % with the rest of the world, making the MENA the least economically integrated region in the world (16). Increased economic growth, expanded markets and economies of scale in production are all advantages of regional integration. Last October, the World Bank offered the Arab Ministerial Council for Electricity (AMCE), operating under the umbrella of the LAS, technical assistance for the creation of the Pan-Arab Electricity Market (PAEM), recognising the importance of increasing the cross-border electricity trade from the current level of 2 % to 40 % by 2035.

The EU could consider supporting initiatives like these. For this purpose, it could work closely with the LAS on institutional cooperation. The 2014 Athens Declaration created a roadmap for cooperation at the institutional level. An advanced dialogue with the LAS is needed and more technical assistance in concrete projects. The EU’s new Global Gateway connectivity strategy, which aims to mobilise up to €300 billion in infrastructure investments between 2021 and 2027, represents a positive step in this direction.

References

*The author would like to thank Caspar Hobhouse, EUISS trainee, for his research assistance.

1. Arab League, ‘Charter of Arab League’ (https://bit.ly/3Ev8ERE).

2. Zacher, M., International Conflicts and Collective Security, 1946-77: The United Nations, Organisation of American States, Organisation of African Unity, and Arab League, Praeger, New York & London, 1979.

3. Mencütek, Z, Ş., ‘The “rebirth” of a dead organisation?: Questioning the role of the Arab League in the “Arab uprisings” process’, Perceptions’, Vol. XIX, No 2, Summer 2014, p.91.

4. Barnett, M and Solingen, E., ‘Designed to fail or failure of design? The sources and institutional effects of the Arab League’, in Johnson, A.I. and Acharya, A. (eds.), Crafting Cooperation: Regional institutions in comparative perspective, Cambridge University Press, New York, 2007, p.213.

5. Pinfari, M., ‘Nothing but failure? The Arab League and the Gulf Cooperation Council as mediators in Middle Eastern conflicts’, Working Paper no. 45, Regional and Global Axes of Conflict, March 2009, p. 11.

6. Ibid. p.10.

7. El Khazen, I. and Kouachi, I., ‘Egypt withdraws from Arab League meeting amid Libya presidency row’, Anadolu, 6 September 2022 (https://www.aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/egypt-withdraws-from-arab- league-meeting-amid-libya-presidency-row/2678364).

8. ‘Designed to fail or failure of design? The sources and institutional effects of the Arab League’, op.cit., p.197.

9. Mezahi, M., ‘Is the success of the Med games a new chapter for Algeria?’, The New Arab, 13 July 2022 (https://www.newarab.com/opinion/success- med-games-new-chapter-algeria).

10. Alilat, F., ‘Can Ramtane Lamamra bring back Algeria’s golden age of diplomacy?’, The African Report, 31 August 2021 (https://www. theafricareport.com/123109/can-ramtane-lamamra-bring-back- algerias-golden-age-of-diplomacy/).

11. Al Jazeera (in Arabic), ‘The Algeria Summit: Palestine, resolving differences and strengthening security and stability are issues that dominate the words of Arab leaders’, 2 November 2022 (https://bit. ly/3ErFoet).

12. Algérie Presse Service (in Arabic), ‘The Algiers Declaration resulting from the Arab summit’, 2 November 2022 (https://www.aps.dz/ar/ algerie/134070-2022-11-02-14-43-54).

13. Ghanem, D., ‘The disease of repression’, Carnegie Middle East Center, 8 April 2020 (https://carnegie-mec.org/diwan/81499).

14. Arab Center Washington D.C., ‘The 2019-2020 Arab Opinion Index: Main Results in Brief’, 6 November 2020 (https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/ the-2019-2020-arab-opinion-index-main-results-in-brief/#section9).

15. Malpass, D., ‘Regional integration in the Middle East and North Africa: A call to action’, World Bank Blogs, Voices – Perspectives on Development, 29 October 2021 (https://blogs.worldbank.org/voices/regional- integration-middle-east-and-north-africa-call-action).

16. Abouzzohour, Y., ‘BDC snapshots: Intra-regional economic integration would boost Maghreb economies’, Brookings, 4 March 2021 (https:// www.brookings.edu/opinions/bdc-snapshots-intra-regional-economic- integration-would-boost-maghreb-economies/).