You are here

Pakistan's polycrisis

Introduction

Pakistan is in the throes of a multifaceted crisis that could result in the collapse of the economy and of the country’s semi-democratic system. Over the course of its history the country has seen three periods of military rule, totalling 33 years. Since 2008, Pakistan has been ruled by a hybrid regime featuring an elected civilian government that informally (and, to some extent, unwillingly) shares power with the country’s army. The army’s role in politics has become more overt since 2018 as both coalition governments that have ruled since then came to power as a result of collaboration with the military against common political foes.

Given Pakistan’s large population, strategic location, and nuclear weapons arsenal, instability in the country may result in cascading negative and disruptive effects not just in South and Central Asia, but also beyond, including in Europe.

The aim of this Brief is to identify the chief drivers of instability in Pakistan today, their potential ramifications beyond the country’s borders, and to provide guidance for EU policymakers on steps that can be taken to help restore economic and political stability in the country. The first section of the Brief examines the simultaneous economic, political and security challenges that have been impacting the country over the past year — what some observers are calling a ‘polycrisis’ (1). The next section looks at the interplay between these three crises and assesses their impact on order, stability and social cohesion in Pakistan. The third section explores how Pakistan’s crises could impact the immediate region, including the stability of the Taliban regime, the behaviour of Islamist terrorist groups in Afghanistan, and the ceasefire along the Line of Control in Kashmir (2) The final section assesses the implications of a meltdown of government and society in Pakistan for the EU, addressing policy priorities such as democracy and human rights, economic stability and migration, competition with China, and climate. It concludes with policy recommendations for the EU as a whole and its Member States.

Unpacking Pakistan's polycrisis

Pakistan is currently facing numerous and mounting threats to order and stability. In particular, intersecting economic, political and security challenges undermine the political system’s authority, legitimacy and overall ability to function, with potential repercussions beyond Pakistan’s borders.

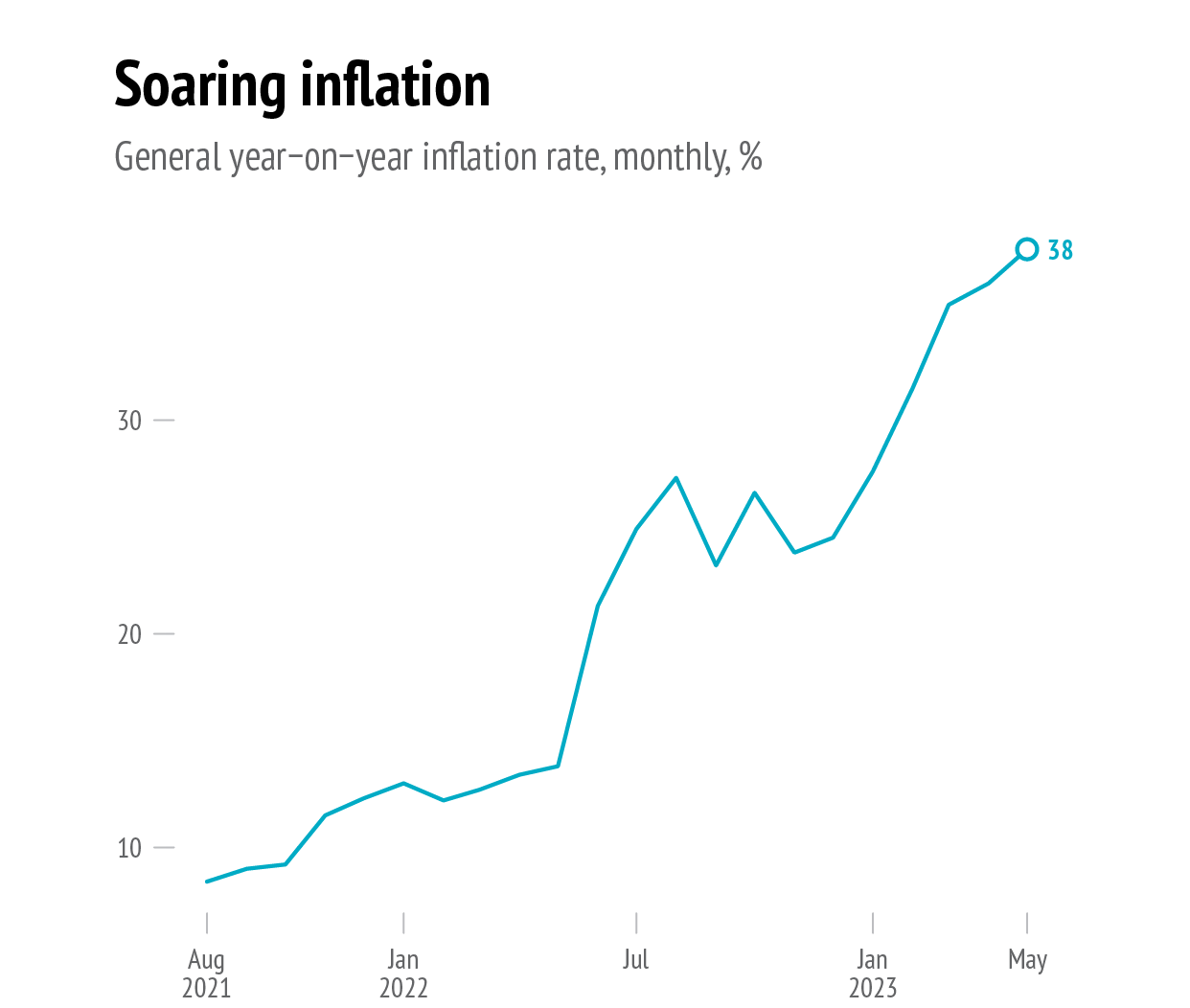

First and foremost, Pakistan’s economy is in deep distress. Since early 2022 Pakistan has had to contend with a balance of payments crisis and surging inflation, which has risen to almost 40 % (3). Pakistan’s macroeconomic woes date back even further to 2018 and are part of recurring boom-bust cycles, generated by unbalanced growth. The pattern is as follows: periods of growth in Pakistan are fuelled by domestic consumption and debt-driven public spending, but exports and foreign direct investment remain at modest levels. Then, to plug the fiscal and current account deficits, Pakistan seeks relief from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and must constrict the economy to achieve macroeconomic stability.

Pakistan is now teetering on the brink of default.

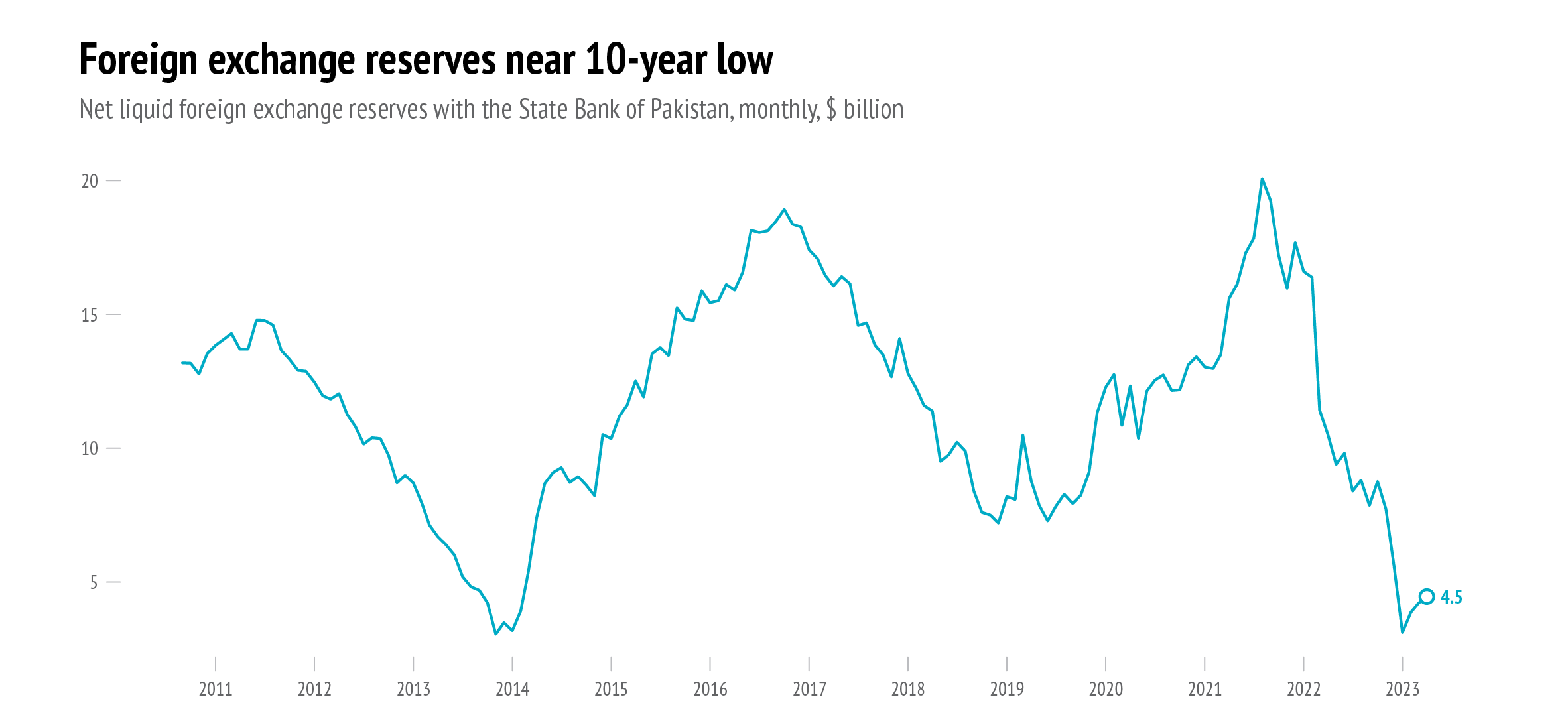

Pakistan is now teetering on the brink of default. Foreign exchange reserves have fallen to less than a month’s worth of imports (4), raising concerns about Islamabad’s ability to repay its external debt. Due to its depleted foreign currency reserves, Pakistan has imposed severe curbs on imports, which have hurt domestic manufacturers, including in the pharmaceutical and textile industries (5). The current economic crisis is the result of the aforementioned imbalances in the Pakistani economy, exacerbated by borrowing to finance infrastructure projects related to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), as well as by the Russia-Ukraine war and the decision by Islamabad to introduce fuel subsidies when global energy prices soared last year.

Data: Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, 2023

To avert default, Pakistan needs to revive its IMF Extended Fund Facility (EEF), which remains stuck at the ninth review and expires in June 2023. The country faces a chicken-or-egg situation: it needs the IMF programme to get back on track to attract inflows of foreign investment that would help reestablish macroeconomic stability. But it also needs guarantees of external financing from friendly states and other multilateral partners to complete the EEF’s ninth review.

By early summer, Pakistan’s default risk will climb to dangerous levels should it fail to complete the ninth review. A recent editorial in Pakistan’s leading English-language daily newspaper, Dawn, has warned that default is now ‘almost inevitable’ (6).

Pakistan’s struggles with its current IMF programme jeopardises its prospects of securing another urgently-needed EEF once the current one expires. A new IMF programme will likely require even tougher policy choices on the part of Islamabad, including the renegotiation of debt with partners like Beijing, its largest bilateral creditor (7). The largest share of Pakistan’s external debt is owed to multilateral institutions like the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the IMF and the World Bank (8).

Data: Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, 2023

The case of Zambia is illustrative of the uphill task Pakistan could face. After defaulting in 2020, Zambia — whose largest bilateral creditor is also Beijing — remains mired in contentious talks with international creditors, including China, over debt restructuring. Zambian President Hakainde Hichilema said in April 2023 that he feels his country ‘is more or less like a guinea pig now’, caught in the tussle between China and more traditional international creditors like the United States over how to restructure developing countries’ debt (9). Beijing is demanding that Lusaka’s multilateral lenders also take a haircut.

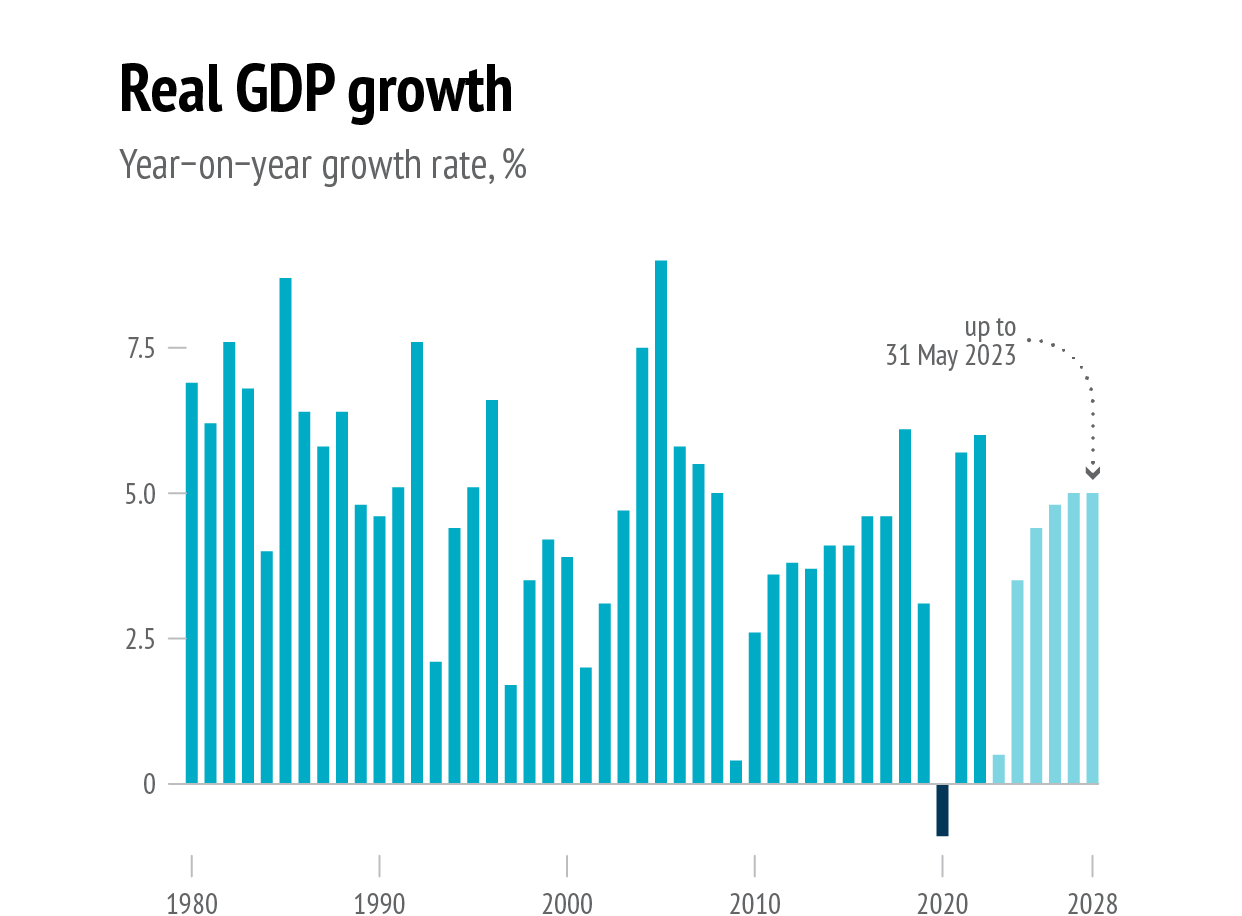

With or without an IMF bailout, in the short term, Pakistan could be locked in a stagflationary cycle. The economy is forecast to grow at a rate of under 1 % in the current fiscal year (10). Inflation reached a six-decade-high in April 2023 (11). As core inflation is proving to be stubborn, some economists also warn of potential hyperinflation (12).

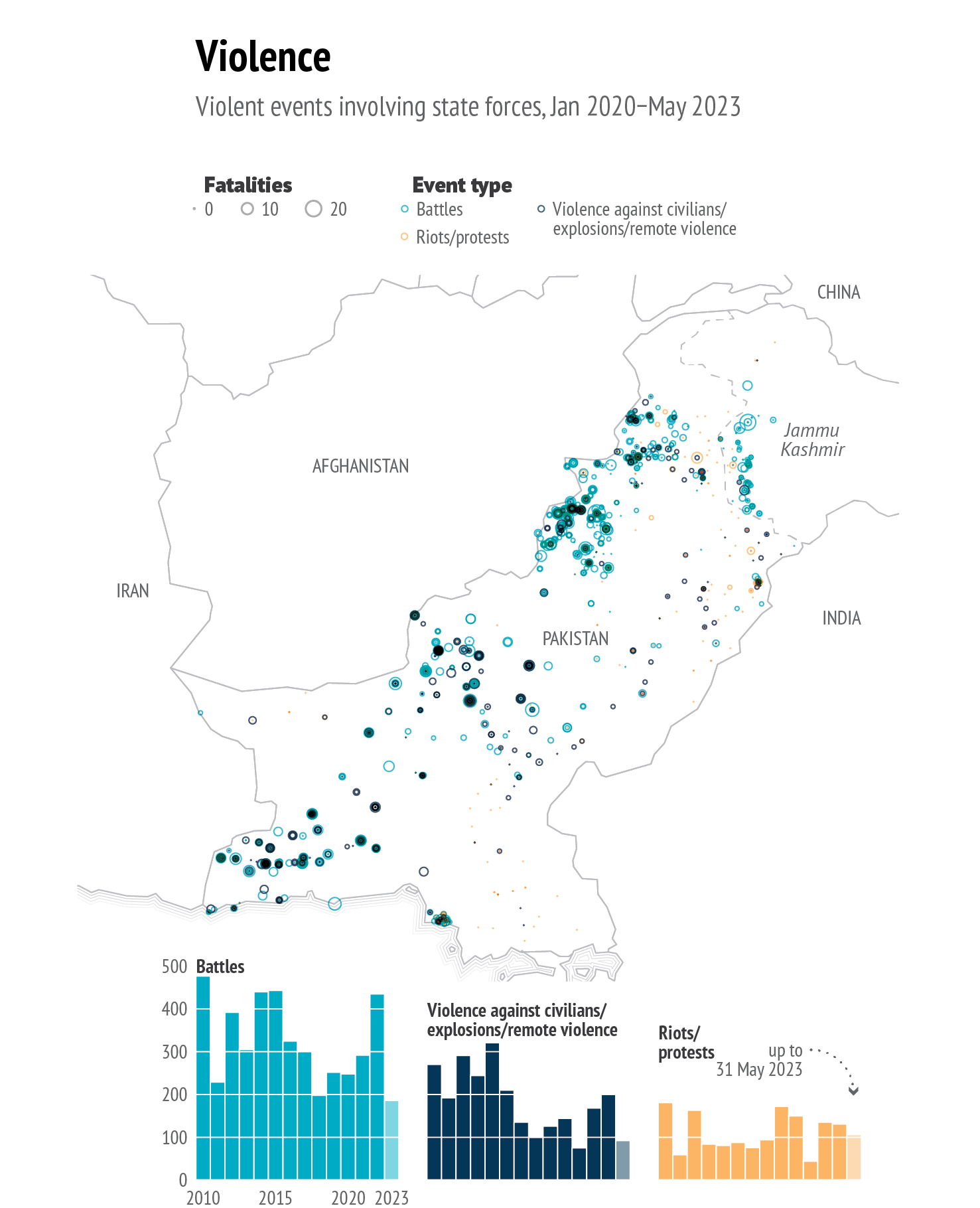

The second challenge to the socio-political cohesion of the Pakistani state is a renewed campaign of ethnic separatist and jihadist terrorism (13). The Tehreek-e Taliban Pakistan (TTP) terror network has reconsolidated in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan. It is regenerating and expanding its networks within Pakistan, including in Balochistan. The TTP and ethnic separatist terrorists are waging attacks against security forces at levels unseen in years. Last year was the deadliest for Pakistani security forces in a decade with 282 fatalities due to attacks by militant groups (14).

These attacks are claiming the lives of not just rank-and-file soldiers, but also army officers and top personnel of the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) (15). Ethnic separatists in Balochistan and Sindh have also been able to carry out a wave of strategically important attacks against Chinese nationals and institutions in Pakistan, in a bid to deter construction and investment related to the CPEC.

Compounding Pakistan’s economic and security challenges is the political crisis that has its origins in the removal of Imran Khan from the premiership through a vote of no confidence in April 2022. Political support for Khan has only grown since he was ousted from power (16). Aware of this groundswell of popular support, the former prime minister has been pushing for general elections to be held earlier than the deadline this autumn, but the unpopular coalition government and army leadership are resisting such pressure (17).

Data: IMF, 2023

Should Pakistan’s National Assembly complete its full term on 13 August 2023, general elections must take place within 60 days, or by 12 October. If the National Assembly is dissolved any time before that, elections must take place within 90 days of its dissolution (18). As a result, the latest possible date for general elections, barring a declaration of emergency, would be 10 November 2023.

Last year was the deadliest for Pakistani security forces in a decade due to attacks by militant groups.

As public support for the ruling coalition and Army erodes, the authorities have resorted to heavy-handed tactics in an attempt to neutralise Khan, who blames top civilian and military officials for a failed assassination attempt on him in November 2022 (19). In the wake of violence targeting military installations on 9 May 2023 following Imran Khan’s arrest after he had travelled to attend a court hearing in the capital (20), the army is now working to dismantle Khan’s Pakistan Movement for Justice (Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf-PTI) party, forcing defections among the party’s senior ranks (21). Khan has enjoyed support from prominent retired army officers as well as low/mid-level serving officers (22). However, the current army chief, General Asim Munir, has taken severe measures to crack down on the ex-cricketer’s supporters within the army and among family members of current and retired officers (23).

In the current tense climate there remain risks that Pakistan’s rulers could seek the deferral of elections well after October 2023. This would mark the first time since 2013 that general elections were not held within the constitutionally-mandated period.

Intra-elite discord also extends to the Supreme Court. The government-backed Election Commission of Pakistan violated a Supreme Court ruling in March 2023 that ordered the holding of elections in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab provinces within or near to the constitutionally-mandated 90-day period after the dissolution of their assemblies (24).

Given the government’s refusal to hold provincial elections, the exasperated Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Pakistan said that the article of the constitution outlining the election schedule has been effectively put in ‘cold storage’ (25).

The parliament has also defied the Supreme Court by refusing to release election funds to the Election Commission (26). The Supreme Court itself is divided into two factions, one led by the Chief Justice Umar Ata Bandial, said to be aligned with Khan, and the other led by Justice Qazi Faez Isa, regarded as being aligned with the current government (27).

In the assessment of one veteran Pakistani political analyst: ‘We are now witnessing a complete breakdown of the system as the ongoing power struggle threatens to bring down the entire structure’ (28).

What's at stake?

The polycrisis represents the most significant challenge to the Pakistani political system since the 1971 civil war, which resulted in the secession of the country’s eastern wing.

The potential combined effect of the current three-headed crisis is that Pakistan could descend into a new spiral of chronic instability and state failure, marked by a paralysed, factionalised elite, leaderless protests, and even mass violence. Yet outright state collapse is highly unlikely given the tremendous coercive power and cohesion of Pakistan’s armed and police forces. Even more fragile states, such as Afghanistan, Syria and Yemen, have survived as de jure entities in recent years despite decades of armed conflict.

Pakistan’s future is more likely to share characteristics with contemporary Iraq, Lebanon and Sri Lanka. The predatory and corrupt ethno-sectarian system of power-sharing that prevails in Iraq and Lebanon has an analogue in Pakistan’s coalition politics (29). Recent political stalemates in these countries also mirror Pakistan’s politico-constitutional crisis. And Pakistan faces the real risk of sovereign default on external loans this year, much as Sri Lanka did last year. Over the next three years, Pakistan will need to repay nearly USD 80 billion in external debt (30).

Unlike recent periods of tumult in Pakistan, two safety valves no longer function as they once did. Firstly, international financial institutions and Pakistan’s chief foreign allies are reluctant to disburse further funds to Pakistan unless stricter conditions are attached. Pakistan’s previous boom-bust cycles have been cushioned by the largesse of Gulf Arab states, China and the United States — countries that viewed it as geostrategically important. Now Pakistan, like Egypt, faces a hard landing as its benefactors demand front-loaded reforms, including increased collection of domestic tax revenue, as mentioned by Saudi Minister of Finance Mohammed Bin Abdullah Al-Jadaan in January (31).

An economic meltdown in Pakistan could severely deplete the coffers of the Taliban regime.

Secondly, the reputation of the army — at times perceived by the public as a non-partisan force that could intervene and establish order — is now tarnished, as it is seen as politically aligned with an unpopular government against a popular opposition party. A fifth of Pakistanis surveyed in late March and early April see the army as ‘primarily responsible’ for Pakistan’s ongoing crisis (32). The army has taken a commanding role in the political crisis; in doing so, it has established a degree of order, but one that may prove fleeting should economic and security conditions deteriorate further.

In seeking to degrade or eliminate the PTI, the army has created a political void in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where the party is popular and a jihadist insurgency has flared up. Repression of the PTI requires continued heavy coercion that could strain the resources of the army and intelligence agencies — a state of affairs of which the TTP would be quick to take advantage.

In the coming months, should Pakistan default, the country could see the same type of leaderless mass protests and outpouring of anger against the elite witnessed in Sri Lanka last year. Thousands of PTI workers and supporters have been detained (33). Further unrest would put the prison system and security services under significant strain.

The economic and social impact of default would be extraordinary: a sharp recession, hyperinflation, massive job losses, and a severe shortage of essential items — including imported food, fuel and medicine. In such dire circumstances Pakistan would experience widespread industrial shutdowns and massive disruption to the country’s electric power supply, and long queues for food and fuel.

Impact on regional stability

Ordinary Pakistanis would bear the brunt of a full-blown economic and political crisis. The impact could to neighbouring Afghanistan, given the economic and security interdependence between the two states.

The Taliban regime is reliant on imports and inflows from Pakistan, including smuggled dollars (34) and taxes on coal exports, for its fiscal stability (35). Customs revenue provided 58 % of the Taliban’s total financial resources in the first 10 months of the 2022-23 fiscal year, according to an assessment by the World Bank. (36). An economic meltdown in Pakistan could severely deplete the coffers of the Taliban regime, depriving it of funds to pay for its military forces, and raising the risk that disaffected fighters could defect to other forces, including the Islamic State-Khorasan (ISIS-K). Deteriorating economic conditions in Pakistan could also result in more forceful calls for the expulsion or extend beyond Pakistan’s borders, particularly repatriation of Afghan nationals by political parties, such as the Muttahida Qaumi Movement – Pakistan (MQM-P), exacerbating the humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan.

China is considerably exposed to the polycrisis unfolding in Pakistan.

Yet, somewhat paradoxically, the Taliban’s reliance on informal and illicit financial and trade networks may actually endow it with the resilience to weather economic tumult in Pakistan. Turmoil in Pakistan could deepen the economic integration of the two ‘sick men’ of South Asia, with an increase in illicit activities like the smuggling of narcotics and other goods.

Deteriorating economic and security conditions in Pakistan may also bolster transnational terrorist networks, including the TTP, al-Qaeda, or ISIS-K, particularly if the Pakistani army’s political activities limit the resources it can devote to counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations and the Taliban faces internal challenges from its rank and file.

In contrast to Afghanistan, India is largely insulated from potential upheaval in Pakistan, given the hard border regime between the two countries. It could actually stand to benefit from turmoil in Pakistan that consumes the country’s leadership but does not spill over into India or Indian-controlled territory. As for the Kashmiri insurgency, policies of economic coercion, such as the greylisting of Pakistan by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), have proven effective in curbing the Pakistan Army’s support for militants in Indian-controlled Kashmir (37). The present Pakistani civilian and military leadership appear committed to adhering to the ceasefire along the Line of Control in the disputed region of Kashmir and engaging New Delhi, as the recent participation of Foreign Minister Bilawal Bhutto Zardari at the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) meeting in Goa indicates. This was the first visit to India by a senior Pakistani official in 12 years.

For its part, China is considerably exposed to the polycrisis unfolding in Pakistan. Ethnic separatist terrorist groups in Pakistan have acquired the power to derail future China-Pakistan economic relations due to their ability to strike Chinese targets, including language teachers, construction workers and engineers. A 2021 terror attack targeted a hotel hosting the Chinese ambassador (38). These attacks necessitate the deployment of Pakistani security personnel to guard Chinese nationals, raising the cost of Chinese electric power and infrastructure projects undertaken as part of the CPEC. Pakistan’s failure to prevent attacks on Chinese nationals has angered Beijing (39) and may deter future aid and investment, especially in more dangerous areas like Gwadar. Pakistan’s economic misgovernance is, however, a bigger source of strain in Sino-Pakistani relations.

Data: ACLED, 2023; European Commission, GISCO, 2023

Immediate security risks to China from rising instability in Pakistan are low given the tight control over the overland border route and the large police state apparatus in Xinjiang. The primary challenge for Beijing right now is diplomatic: as Pakistan’s largest bilateral creditor (40), it is being pressed to renegotiate Pakistani debt, much as in the case of Sri Lanka. Beijing is worried about a precedent being established. In the longer term, however, should conditions in Pakistan and Afghanistan deteriorate, China faces the dangers of two fragile states along its western frontier.

An economic meltdown and socio-political upheaval in a country of 220 million people would also have global ramifications. Pakistan already experienced a significant jump in regular emigration in 2022 (41). First-time asylum applications lodged in the EU by Pakistani citizens rose sharply in 2022 compared to 2021 (42). Pakistani nationals made up the sixth-largest nationality of asylum-seekers in the EU in 2022 (43). More and more desperate, young Pakistanis in search of a better future, unable to obtain visas for entry to Western countries, will be forced to choose the path of irregular migration, undertaking perilous journeys to reach Europe. With a whole generation of young people deprived of legitimate opportunities for gainful employment, human trafficking, the smuggling of narcotics and other illicit goods, as well as cybercrime, will likely rise in Pakistan.

Policy recommendations for the EU

For EU Member States, the main impact of the turmoil in Pakistan may be a rise in irregular migration.The EU is Pakistan’s second-largest trading partner and the destination for over a quarter of its exports (46). Pakistani exports to the EU have grown by 65 % since GSP+ status was granted to the country in 2013. (47)

The expansion of exports is key for Pakistan to exit its balance of payments crisis. As a result, the non-renewal or suspension of GSP+ due to worsening human rights and good governance conditions in Pakistan may cause unintended harm. The EU should identify a range of more targeted responses to a military takeover, a potential high-profile assassination perpetrated by Pakistani state actors, or egregious human rights abuses. A more effective response, for example, could be the imposition of sanctions on individuals under the European Magnitsky Act of 2020 (48).

Supporting democratic continuity in Pakistan not only reflects the EU’s liberal values, but is also critical for Pakistan’s political stability. The EU should both privately and in discreet public utterances affirm the need for all actors in Pakistan to uphold the constitution and human rights. It should also encourage a negotiated resolution to the political crisis within the bounds of the Pakistani constitution.

The EU has a potential role to play in Pakistan’s economic transformation beyond the present crisis, including in green energy and technology. Through its Global Gateway strategy, the EU should consider supporting green hydrogen projects in the Balochistan and Sindh provinces. Replacing imported fossil fuels with domestic renewable fuel sources in the industrial and heavy transportation sectors would also help Pakistan conserve its foreign exchange reserves (49). The European Investment Bank (EIB) can also consider working with startup funds that are active in Pakistan, helping accelerate the growth of the country’s technology industry, building on the ‘Accelerate Prosperity in Asia’ project (50) which is jointly funded by the Aga Khan Foundation and the EU.

The EU, through signature initiatives, can assert its strategic autonomy and provide an alternative to Pakistan and other countries in the Global South that currently feel compelled to choose between the two protagonists in the climate of US-China rivalry.

Conclusion

The polycrisis in Pakistan represents a significant threat to the stability of a pivotal state at the crossroads of South and Central Asia, bordering China, India and Iran, with potential ripple effects and repercussions in Europe. Without a broad-based political consensus, Pakistan is unlikely to be able to overcome these multiple crises.

While the Pakistan army’s campaign to sideline Imran Khan appears to be succeeding so far (51), it is severely undermining fundamental rights (52), judicial independence, press freedoms (53) and Pakistani democracy itself in the process. Given the popularity gap between Khan and his rival politicians (54), excluding Khan is unlikely to yield stability, at least without sustaining a system of fearsome coercion. The military‘s arm of repression in the ongoing crackdown on dissent is beginning to extend beyond the network of the PTI and its supporters (55), and may eventually trigger a backlash against the army from non-PTI activists and politicians.

On the economic front, the outlook is similarly gloomy. As the window of opportunity for Pakistan to revive its IMF bailout programme closes, the potential for an even deeper and more painful economic crisis grows. There are some reports that the government in Islamabad may dedicate its efforts instead towards negotiating a new EFF with the IMF later this summer, enabling it to first pass a budget in June that is friendly to voters (56). But that will do little in the coming weeks to arrest the decline in Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves. By kicking the can down the road, Pakistan’s rulers will only exacerbate the deepening crisis as they must secure an IMF agreement to avert default prior to transferring power to a caretaker government to oversee elections in the autumn. The odds are against them and the risk of a declaration of emergency is real.

It is neither desirable nor possible for outside powers, including the EU, to become enmeshed in Pakistan’s factional disputes at such a volatile time. Ultimately, these are Pakistani problems that require Pakistani solutions.

However, the EU and other Western economies have the policy tools that can help dissuade Pakistan’s leaders from an escalation that would take the crisis beyond the point of no return and result in full-scale military rule. The EU also has instruments, such as the Global Gateway, that support sectors that would foster green and sustainable growth and overall macroeconomic stability in Pakistan.

References

1. Lodhi, M. ‘Year of polycrisis’, Dawn, 2 January 2023 (https://www.dawn. com/news/1729501/year-of-polycrisis/). The World Economic Forum popularised the use of the term ‘polycrisis’ in its Global Risks Report 2023. It defines ‘polycrisis’ as ‘a cluster of related global risks with compounding effects, such that the overall impact exceeds the sum of each part’. This report uses the term specifically in Pakistan’s domestic context. See: World Economic Forum, ‘We’re on the brink of a polycrisis — how worried should we be?’ 13 January 2023 (https://www.weforum. org/agenda/2023/01/polycrisis-global-risks-report-cost-of-living/).

2. The latest annual report of the Indian Home Ministry states that what it calls ‘terrorist infilitration’ attempts across the Line of Control and Working Boundary in Jammu and Kashmir fell to a five-year low in 2021. See: Manral, M., ‘J&K reported 73 infiltration bids in 2021, lowest in 5 years’, The Indian Express, 8 November 2022 (https://indianexpress.com/ article/india/jk-reported-73-infiltration-bids-in-2021-lowest-in-5- years-8255320/).

3. Shahid, A., ‘Food pushes Pakistan inflation to record 36.4% in April’, Reuters, 2 May 2023 (https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/pakistan- inflation-hits-record-364-april-highest-region-2023-05-02/).

4. State Bank of Pakistan, ‘Liquid foreign exchange reserves’, 4 May 2023 (https://www.sbp.org.pk/ecodata/forex.pdf).

5. Hanif, U., ‘Textiles on verge of collapse’, The Express Tribune, 15 March 2023 (https://tribune.com.pk/story/2406092/textiles-on-verge-of- collapse).

6. ‘Money Talks’, Dawn, 19 May 2023 (https://www.dawn.com/ news/1754320/money-talks).

7. Alam, K., ‘Debt restructuring will be “very difficult”: ex-SBP chief’, Dawn, 5 April 2023 (https://www.dawn.com/news/1746005/debt- restructuring-will-be-very-difficult-ex-sbp-chief)

8. Rana, S., ‘Pakistan’s existential economic crisis’, United States Institute of Peace, 6 April 2023 (https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/04/ pakistans-existential-economic-crisis).

9. Steinhauser, G., ‘Debt standoff between China and U.S. hurts poor countries, Zambia’s President warns’, Wall Street Journal, 10 April 2023 (https://www.wsj.com/articles/debt-standoff-between-china-and-u-s- hurts-poor-countries-zambias-president-warns-3f34f762).

10. Haider, K., ‘Pakistan’s inflation outpaces Sri Lanka as Asia’s fastest’, Bloomberg, 2 May 2023 (https://www.bloomberg.com/news/ articles/2023-05-02/pakistan-s-inflation-hits-record-with-no-sign- yet-of-imf-funds).

11. Pasha, H., ‘The IMF projections’, Business Recorder, 18 April 2023 (https:// www.brecorder.com/news/40237719/the-imf-projections).

12. ‘Pasha warns of stagflation this year’, Business Recorder, 18 January 2023 (https://www.brecorder.com/news/40220851).

13. Ethnic separatist militant groups in the southern Balochistan and Sindh provinces include the Baloch Raji Aajoi Sangar, Balochistan Liberation Army, Balochistan Liberation Front, Balochistan Republican Army, Sindhudesh Liberation Army, Sindhudesh People’s Army, and the Sindudesh Revolutionary Army.

14. ‘2022 ends with deadliest month for security forces after decade: report’, Dawn, 1 January 2023 (https://www.dawn.com/news/1729229/2022- ends-with-deadliest-month-for-security-forces-after-decade-report).

15. ‘ISI Brigadier Mustafa Kamal Barki laid to rest with full military honours’, Samaa, 22 March 2023 (https://www.samaaenglish.tv/ news/40029808).

16. Rafiq, A., ‘Survey: Ex-PM Imran Khan Is Pakistan’s most popular politician’, Globely News, 6 March 2023 (https://globelynews.com/ south-asia/imran-khan-popularity-graph-2023/).

17. ‘Maryam Nawaz says elections to be held in October’, ARY News, 1 May 2023 (https://arynews.tv/maryam-nawaz-says-elections-to-be-held- in-october/).

18. National Assembly of Pakistan, ‘The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan’ (https://na.gov.pk/uploads/documents/1333523681_951.pdf).

19. Sharma, S., ‘Imran Khan blames new Pakistan PM for assassination attempt as his angry supporters protest’, The Independent, 4 November 2022 (https://www.independent.co.uk/asia/south-asia/imran-khan- shot-blames-men-assassination-attempt-b2217431.html).

20. ‘Imran Khan: Deadly violence in Pakistan as ex-PM charged with corruption’, BBC News, 11 May 2023 (https://www.bbc.com/news/world- asia-65541215).

21. Hussain, A., ‘Why have dozens of leaders quit Imran Khan’s party in Pakistan?’, Al Jazeera, 24 May 2023 (https://www.aljazeera.com/ news/2023/5/24/why-have-dozens-of-leaders-quit-imran-khans- party-in-pakistan).

22. Hadid, D., ‘In Pakistan, political and economic problems have many fearful of history repeating’, NPR, 25 April 2023 (https://www.npr. org/2023/04/25/1172007302/in-pakistan-political-and-economic- problems-have-many-fearful-of-history-repeati).

23. Faraz, A., ‘Corps Commander House attack: Police take Khadija Shah into custody’, The News, 23 May 2023 (https://www.thenews.com.pk/ latest/1073244-corps-commander-house-attack-police-take-khadija- shah-into-custody).

24. Sadozai, I., ‘ECP postpones Punjab elections to October 8’, Dawn, 22 March 2023 (https://www.dawn.com/news/1743591/ecp-postpones- punjab-elections-till-october-8).

25. ‘Article 224 can’t be held in abeyance: SC’, The Express Tribune, 25 May 2023 (https://tribune.com.pk/story/2418553/for-how-long-can- constitutional-provisions-be-held-in-abeyance-asks-sc).

26. Sherani, T., ‘As SC deadline looms, NA rejects motion seeking supplementary sum of Rs21bn for polls in Punjab’, Dawn, 17 April 2023 (https://www.dawn.com/news/1748139).

27. Malik, H., ‘No breakthrough in internal SC dispute’, The Express Tribune, 4 April 2023 (https://tribune.com.pk/story/2409718/no-breakthrough-in- internal-sc-dispute).

28. Hussain, Z., ‘Talks to nowhere’, Dawn, 3 May 2023 (https://www.dawn. com/news/1750606).

29. The term ‘consociationalism’ is sometimes used to denote this type of consensus-based powersharing arrangement in deeply divided, plural societies.

30. Rana, S., ‘Pakistan’s existential economic crisis’, U.S. Institute of Peace, 6 April 2023 (https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/04/pakistans- existential-economic-crisis).

31. Rafiq, A., ‘“Too big to fail” no longer works for Egypt and Pakistan’, Globely News, 5 February 2023 (https://globelynews.com/middle-east/ egypt-pakistan-saudi-arabia-gcc-imf/).

32. Pattan Development Organisation, ‘Pattan opinion poll on Punjab and KPK elections’, April 2023 (http://pattan.org/v2/wp-content/ uploads/2023/04/Current-survey-April-2023-analysis-final-2.pdf).

33. ‘Imran Khan claims plan afoot to ban PTI amid crackdown on May 9 rioters’, Geo News, 21 May 2023 (https://www.geo.tv/latest/488613- imran-khan-claims-plan-afoot-to-ban-pti-amid-crackdown-on-may- 9-rioters).

34. Najafzada, E. and Dilawar, I., ‘Dollars smuggled from Pakistan provide lifeline for the Taliban’, Bloomberg, 7 February 2023 (https://www. tbsnews.net/bloomberg-special/dollars-smuggled-pakistan-provide- lifeline-taliban-581246).

35. AFP, ‘Afghanistan coffers swell as Taliban taxman collects’, 9 March 2023 (https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20230309-afghanistan- coffers-swell-as-taliban-taxman-collects).

36. World Bank, ‘Afghanistan Economic Monitor’, 24 February 2023 (https:// documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099051823102061044/pdf/ P17861105b651f0580a3750a0eda1073b18.pdf).

37. Press Trust of India, ‘Terror attacks declined after Pak’s inclusion in FATF grey list, Indian official tells UNSC panel’, Times of India, 28 October 2023 (https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/india/terror-attacks- declined-after-paks-inclusion-in-fatf-grey-list-indian-official-tells- unsc-panel/articleshow/95151070.cms).

38. Ni, V., ‘China condemns bombing of Pakistan hotel hosting ambassador’, The Guardian, 22 April 2021 (https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/ apr/21/four-killed-in-bomb-explosion-at-pakistan-hotel-hosting- chinese-ambassador).

39. After a 2022 attack on Chinese nationals in Karachi, the Chinese state-run Global Times warned that there would be harsh consequences for those targeting Chinese nationals. See: ‘Any forces that target Chinese nationals in attacks will be stricken hardest: Global Times editorial’, Global Times, 27 April 2022 (https://www.globaltimes.cn/ page/202204/1260441.shtml).

40. Hawkins, A., ‘Pakistan’s fresh £580m loan from China intensifies debt burden fears’, The Guardian, 23 February 2023 (https://www.theguardian. com/world/2023/feb/23/pakistan-loan-china-intensifies-debt-burden- fears).

41. Ahmed, W., ‘Country’s brain drain situation accelerated in 2022’,The Express Tribune, 12 December 2022 (https://tribune.com.pk/ story/2390704/countrys-brain-drain-situation-accelerated-in-2022).

42. Eurostat, ‘Annual asylum statistics’, 15 March 2023 (https://ec.europa. eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Annual_asylum_ statistics).

43. Ibid.

44. European Union, ‘2019 EU–Pakistan Strategic Engagement Plan (SEP)’ (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/eu-pakistan_strategic_ engagement_plan.pdf).

45. Delegation of the European Union to Pakistan, ‘European Union GSP+ mission arrives to assess progress in implementation of international conventions’, 22 June 2022 (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/delegations/ pakistan/european-union-gsp-mission-arrives-assess-progress- implementation_en?s=175).

46. European Commission, ‘Pakistan – EU trade relations with Pakistan. Facts, figures and latest developments’, (https://policy.trade.ec.europa. eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/ pakistan_en).

47. ‘European Union is largest importer of Pakistani exports, more than the US and China combined, says EU Envoy’, Pakistan Today, 19 February 2022 (https://www.pakistantoday.com.pk/2022/02/19/european-union- is-largest-importer-of-pakistani-exports-more-than-the-us-and- china-combined-says-eu-envoy/).

48. The European Magnitsky Act establishes an EU-wide sanctions regime targeting individuals and organisations ‘responsible for serious human rights violations’ including arbitrary arrests and killings, as well as torture. See: European Parliament, ‘A European Magnitsky Act’ (https:// www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/theme-a-stronger-europe- in-the-world/file-a-european-magnitsky-act).

49. The EU Global Gateway has identified flagship projects for 2023 in Bangladesh and Nepal linked to green recovery and green technology. See: European Union, ‘EU-Asia and the Pacific flagship projects for 2023’, March 2023 (https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/ system/files/2023-05/Asia-Pac-flagship-projects-for-2023-v10.pdf).

50. The European Union is among the funders of the Accelerate Prosperity programme. See: Accelerate Prosperity, ‘Donors and Partners’ (https:// accelerateprosperity.org/partners).

51. ‘Deserters continue to dig holes in PTI ship, believes Imran’, Dunya News, 30 May 2023 (https://dunyanews.tv/en/Pakistan/727926-PTI- deserters-lobbying-for-further-breakup,-claims-Imran-Khan).

52. Human Rights Watch, ‘Pakistan: Don’t try civilians in military courts’, 31 May 2023 (https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/05/31/pakistan-dont-try- civilians-military-courts).

53. Reporters Without Borders, ‘Where is the Pakistani TV anchor who has been missing for 12 days?’, 23 May 2023 (https://rsf.org/en/where- pakistani-tv-anchor-who-has-been-missing-12-days).

54. Bari, S., ‘Too large to manage — even by rigging’, The Express Tribune, 10 May 2023 (https://tribune.com.pk/story/2415878/too-large-to-manage- even-by-rigging).

55. ‘Activist Jibran Nasir ‘abducted’ in Karachi, says wife’, The Express Tribune, 2 June 2023 (https://tribune.com.pk/story/2419777/activist- jibran-nasir-abducted-in-karachi-says-wife).

56. Nazar, Y., ‘Govt decides to abandon IMF program, negotiate new one later’, Aaj News, 1 June 2023 (https://www.aajenglish.tv/ news/30323200).