Political instability in one country will inevitably have a particularly strong spillover effect across its borders (1). The takeover of power by the Taliban in August 2021 and the re-establishment of their regime in Afghanistan represented a shock to regional and transnational security dynamics, with neighbouring countries fearing that activities of Islamist terrorist groups present in Afghanistan would spill over into their territory. The Taliban maintain close ties with Islamist terrorist groups, essentially acting as their protector. Some, such as the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), an Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) affiliate, include former Taliban among their membership. This is notwithstanding the declaration by Zabihullah Mujahid, the spokesman of the Taliban government, at their first press conference in Kabul, that the new regime was committed to ensuring security (2). While no high-profile attack has occurred in Europe since August 2021, the assumption that the Taliban has a purely local agenda that does not extend beyond the borders of Afghanistan fails to take into account the various regional and transnational networks that have been built since the 1980s.

With these considerations in mind, this Brief explores security risks for the EU emanating from Afghanistan by assessing the evolving Islamist terrorism threat since the Taliban regained control of the country in August 2021. In order to evaluate how the EU should respond, the first section outlines the current status of the different Islamist terrorist groups currently present in Afghanistan (3) and their regional connections. This section focuses on the relationship between the Afghan Taliban, al-Qaeda, ISKP, Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), and the East Turkistan Islamic Movement (ETIM). Due to this Brief’s limited scope, the regional arena in this context refers to Afghanistan and its neighbouring countries, namely Pakistan, China, Iran and the Central Asian Republics (CARs). The second section examines the transnational effects of the Taliban takeover by focusing on West Africa, which has become a safe haven for al-Qaeda and ISIS affiliates. Finally, the Brief provides a set of policy recommendations for the EU, specifically through a counterterrorism lens, based on the analysis of different Islamist terrorist groups operating both within and outside of Afghanistan’s borders.

The regional dimension

The principal challenge when assessing the growing Islamist terrorist threat emanating from Afghanistan is the ongoing relationship of the Taliban movement with a range of Islamist terrorist organisations. This relates both to questions of internal stability as well as emerging cross-border ramifications for neighbouring countries.

The continuing symbiotic relationship between the Taliban and al-Qaeda and its affiliates operating in Afghanistan is based on a strategic agreement between the leadership of both groups that dates back three decades. Interestingly, the strength of this relationship did not falter following the removal of the Taliban regime in 2001 as a direct result of both the al-Qaeda organised attacks on 9/11 and the US invasion of Afghanistan, and survived several leadership changes in both groups, as reflected in two UN Security Council resolutions from 2011 and 2015 (4). Two UN reports, from 2021 and 2022, document that following the re-establishment of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, and despite Taliban assurances in the Doha Accords signed in February 2020, al-Qaeda maintains a close alliance with the Taliban (5).

The Taliban regime has started to issue Afghan passports to members of terrorist organisations operating in the country.

More specifically, the UN report from 2022 points to the presence, both in Afghanistan and the wider region, of al-Qaeda’s core leadership, including its affiliated groups, such as al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) (6). The shared ideological platform based on political Islam that continues to link the two groups (to the extent that a rift between them seems highly unlikely) is reflected in al-Qaeda leaders’ pledges of allegiance to successive Taliban leaders. Furthermore, the US-led drone attack that killed al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri in Kabul at the end of July 2022 has again demonstrated this close connection. According to a January 2021 memorandum from the US Department of the Treasury, al-Qaeda had gained strength in Afghanistan in the year leading up to the Taliban takeover, while continuing to operate under the Taliban’s protection (7). There is truth in one analyst’s observation that ‘the Taliban takeover was an al-Qaeda victory, too’ (8).

In the context of foreign terrorist fighters (FTFs) travelling to Afghanistan, no significant - and visible - flows have been identified, yet. Between 8 000 and 10 000 FTFs currently operate in Afghanistan, with most having travelled from Pakistan, but also from the region of Central Asia, from the North Caucasus region of Russia and the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region of China (9). In addition, the majority of the FTFs (ranging from 3 000 to 4 000) in Afghanistan are affiliated with the Taliban, more specifically the TTP (10). Alarmingly, there have been official reports from neighbouring countries which suggest that the Taliban regime has started to issue Afghan passports to members of terrorist organisations operating in the country (11), which poses a significant security concern. The risk is that once FTFs leave the country with newly assumed identities and Afghan passports, issued using false identities, their identification by intelligence agencies will become significantly more challenging.

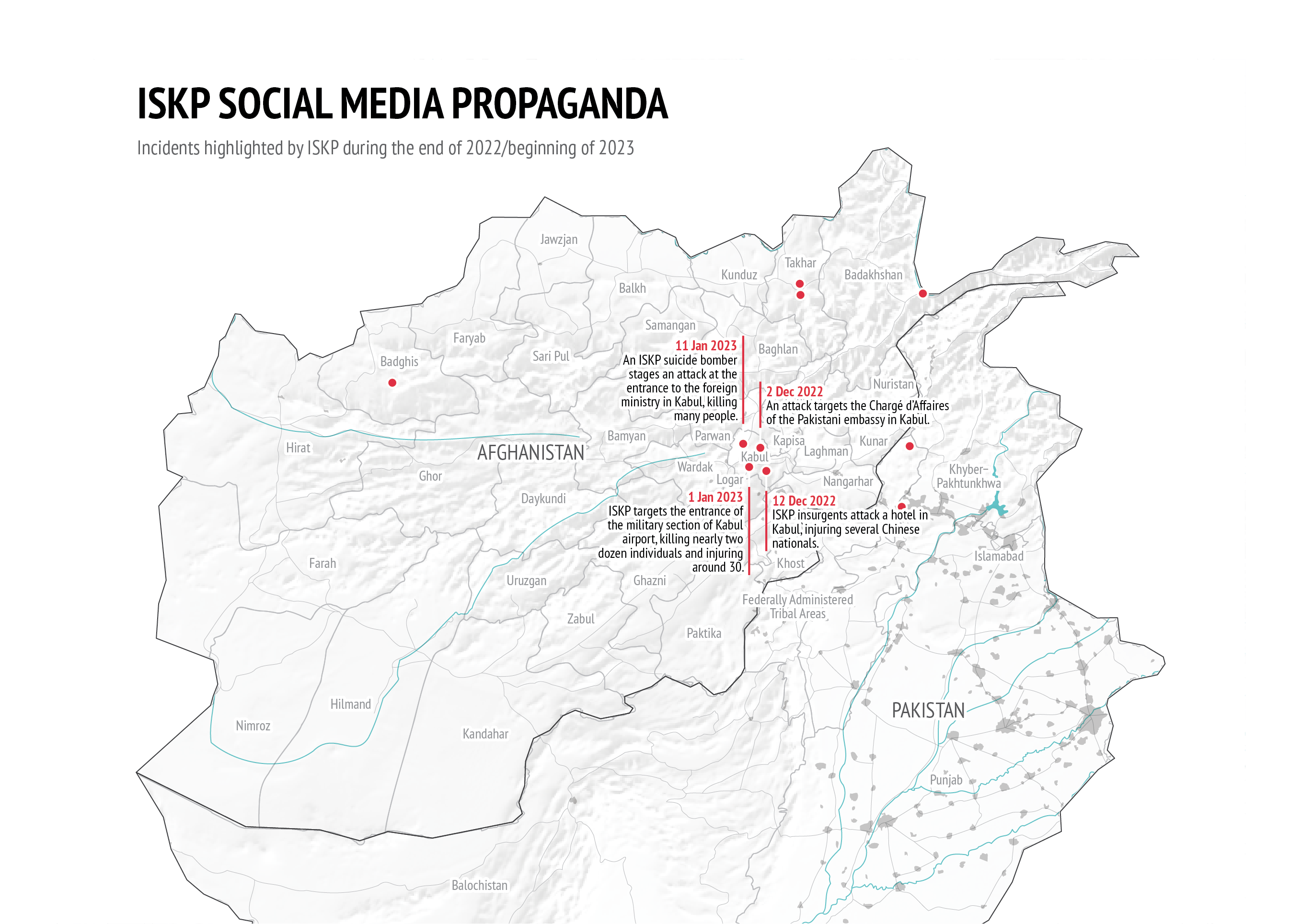

Although the Taliban are in control of all the territory of Afghanistan, internal security challenges remain. For example, the National Resistance Front (NRF), a growing resistance movement of former Taliban officials, local militia members and Afghan security forces, has been carrying out guerrilla attacks against the Taliban – and will continue to do so (12). In addition to factional infighting (13) among the Taliban, frequent attacks by the ISKP occur, including high-profile attacks, such as those targeting the foreign ministry, the military airport in Kabul, the Pakistani embassy and a hotel where Chinese business representatives were staying that occurred in 2022 and early 2023 (14). Throughout 2022, the ISKP was able to maintain a high operational tempo. On 4 January 2023, ISIS published an overview of all ISIS-claimed attacks within Afghanistan from the year 2022 in their propaganda news outlet, Amaq. The infographic alleges that the group had conducted 181 attacks overall, with a toll of 1 188 victims (15).

While it is difficult to verify these figures in detail, this presents a significant increase as compared to 2020 when the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) registered 11 ISKP-linked attacks (16). The overall number of ISKP-claimed attacks declined towards the end of 2022, but it is not uncommon for violence to decrease during the winter months in Afghanistan as adverse weather conditions restrict movement for terrorist operatives. Therefore, ISKP remains a significant security threat in Afghanistan, albeit currently it does not have the ability to destabilise the Taliban regime strategically.

Tehran seems concerned that the situation in Afghanistan could lead to a proliferation of Sunni extremist groups at its border.

Since it was established in 2015, ISKP has included within its ranks a significant number of former Taliban, including from the Haqqani Network (HN), as well as Pakistani fighters, primarily from the TTP. In addition, ISKP was able to include former members of the al-Qaeda affiliate Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), and individuals previously affiliated with core al-Qaeda. ISKP attacks against members of al-Qaeda and its affiliates in Afghanistan have not occurred since 2021. However, this may change due to increasingly virulent ISIS-inspired rhetoric in their propaganda against al-Qaeda (17). ISKP’s antipathy towards the Taliban and al-Qaeda is rooted in differing ideologies. ISKP subcribes to the Takfiri interpretation of Jihad, characteristic of the global ISIS network, and brands anyone outside their group, including the Taliban and al-Qaeda, as unbelievers. In an interview, an active member of ISKP explained why he is fighting against the Taliban regime: ‘They don’t implement Islam and Sharia [the Islamic law system] properly but work for infidels’ (18).

Data: Counter Extremism Project, 2023; European Commission, GISCO, 2023

The UN Secretary-General reported in January 2022 that the number of ISKP recruits had doubled in less than a year, increasing from approximately 2 200 fighters to nearly 4 000 fighters with half of them being FTFs (19). Additionally, ISKP membership has reportedly been boosted by detained fighters, including senior leaders and commanders as well as media propagandists from various countries, who either were released or managed to escape during and after the Taliban’s takeover from both Bagram Air Base and Pul-e-Charkhi prison outside Kabul (20). The diverse membership of ISKP complicates Taliban operations against ISKP as increasing pressure on the group by the Taliban carries the risk of defections from within the Taliban. This, in turn, can spiral into intra-Taliban factionalism, which is becoming more apparent post-August 2021 (21).

ISKP has ambitions that are not limited to the territory of Afghanistan. This can be explained by the difference between the conception of a global caliphate to which ISKP subscribes compared to an emirate based on national boundaries that the Taliban aims to form (22). As previously outlined, not only did the group signal throughout 2022 with high-profile attacks against Pakistani and Chinese (and also Russian (23)) targets in Afghanistan that it will target governments that it perceives to be willing to cooperate with the Taliban, but the movement also increasingly claims responsibility for attacks within the wider region. For example, ISKP highlighted alleged rocket attacks against Uzbekistan and Tajikistan in April and May 2022 respectively (24).

Pakistan is traditionally a key stakeholder in Afghan affairs. The country’s continuing relationship with the Taliban throughout the past two decades was one of the key factors ensuring the Taliban’s survival as an insurgency and their eventual seizure of power in Afghanistan (25). Consequently, it has been suggested in some quarters that the Taliban takeover was also a considerable success for Pakistan. Through the Taliban, Pakistan is able to bolster its influence in Afghanistan as well as advance its long-term efforts to limit India’s influence in the country, although Pakistani officials have claimed that their leverage over the Taliban regime remains limited post-August 2021 (26).

However, for Pakistan, the Taliban’s tolerance of the TTP is highly problematic. The TTP is a conglomerate of violent insurgent groups that seek to overthrow the state of Pakistan. In 2014, some TTP fighters pledged allegiance to ISIS and subsequently defected, relocating to the eastern part of Afghanistan. Since 2020, the TTP has reunified with a few former splinter groups, possibly facilitated by al-Qaeda, and the group’s ranks have swelled as a result. A UN report from July 2022 details that the TTP is ‘now more cohesive, presenting a greater threat in the region’. While unlikely at this point, a strategic alliance between the TTP and ISKP remains a possibility. However, after the US-Taliban Doha accord, the Taliban made efforts to curtail the movement of TTP fighters in Afghanistan, as well as that of other Islamist terrorist groups present in the country. By so doing, the Taliban has sought to distance itself from the TTP’s fight against Pakistan. The TTP has significantly increased its attacks against Pakistani security forces since the Taliban’s return to power in 2021. In October 2021, then-Pakistani prime minister Imran Khan announced that his government was negotiating with parts of the TTP, in talks reportedly arranged by the HN (27).

Turning to China, the Taliban’s acceptance of the ETIM is a matter of concern for Beijing as the main objective of China’s counterterrorism strategy is to combat the potential unrest caused by ETIM. The terrorist group seeks an independent state (East Turkestan) and aims to cover an area including parts of Turkey, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region (XUAR). Beijing accuses ETIM of exerting influence in Xinjiang, and since over 11 million Uighurs live in that province, the group became subject to great scrutiny, with the authorities launching a crackdown and interning many Uighur Muslims in secretive indoctrination camps in the region. Experts perceive the risk of radicalisation or links to international terrorism among the Uighurs to be minor (28). Due to growing pressure from China, ETIM fighters have been forced to relocate from Pakistan to the northeast of Afghanistan. Their movement into Afghanistan was facilitated by the HN (29). A UN report from February 2022 indicates that the Taliban’s ‘efforts to control ETIM fighters inside of Afghanistan’ might ‘push them closer to Taliban rival ISKP, and further out of Taliban control’ (30).

Furthermore, since the Taliban have been welcoming Chinese investment in Afghanistan, the 13 December 2022 attack at the Kabul hotel has been portrayed as ISKP taking concrete action to challenge the government in China. China has, unsurprisingly, adopted a cautious and pragmatic position towards the Taliban in Afghanistan. The relationship between the two states has mostly been friendly in the past and Xi Jinping has stressed the importance of Afghanistan to regional security and stability. China’s engagement with the Taliban regime seems primarily focused on potential investments in and strategic control over Afghanistan’s natural resources, in particular high-value resources such as rare earths (31) and minerals as in the case of the Mes Aynak copper mine (32).

In addition, Afghanistan is geographically close to Central Asia, with the wider region sharing common languages, such as Uzbek, Tajik, Dari and Turkmen. Reportedly, ISKP has been focusing on broadening its networks in Central Asia and has expressed its ambitions to gain power in Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan (33). Some ISKP-linked cross-border attacks have occurred (34) and the CARs have expressed their concerns about terrorism publicly. The Uzbek government has shown commitment to maintaining a diplomatic relationship with Afghanistan and mediating between the Taliban government and the rest of the world (35). These efforts were, for example, demonstrated by Uzbekistan hosting its third global conference on Afghanistan, attended by representatives from over 30 countries, including the United States, in the summer of 2022 (36). Besides Uzbekistan, China and Russia have also held special regional conferences on Afghanistan (37). However, since the Taliban takeover, ISKP has been ramping up the outreach of its official branch media organ, al-Azaim, and adding translated propaganda in Tajik, Uzbek and other regional languages, thereby exploiting regional grievances. From September 2021 until 26 April 2022, around 150 audio files were released (38) and hundreds of individuals, either affiliated with the IMU or other extremist groups from Central Asia, have proceeded to pledge allegiance to ISIS (39). ISKP will likely seek to further engage with terrorists in Central Asia if the group continues to strengthen its position in the north of Afghanistan.

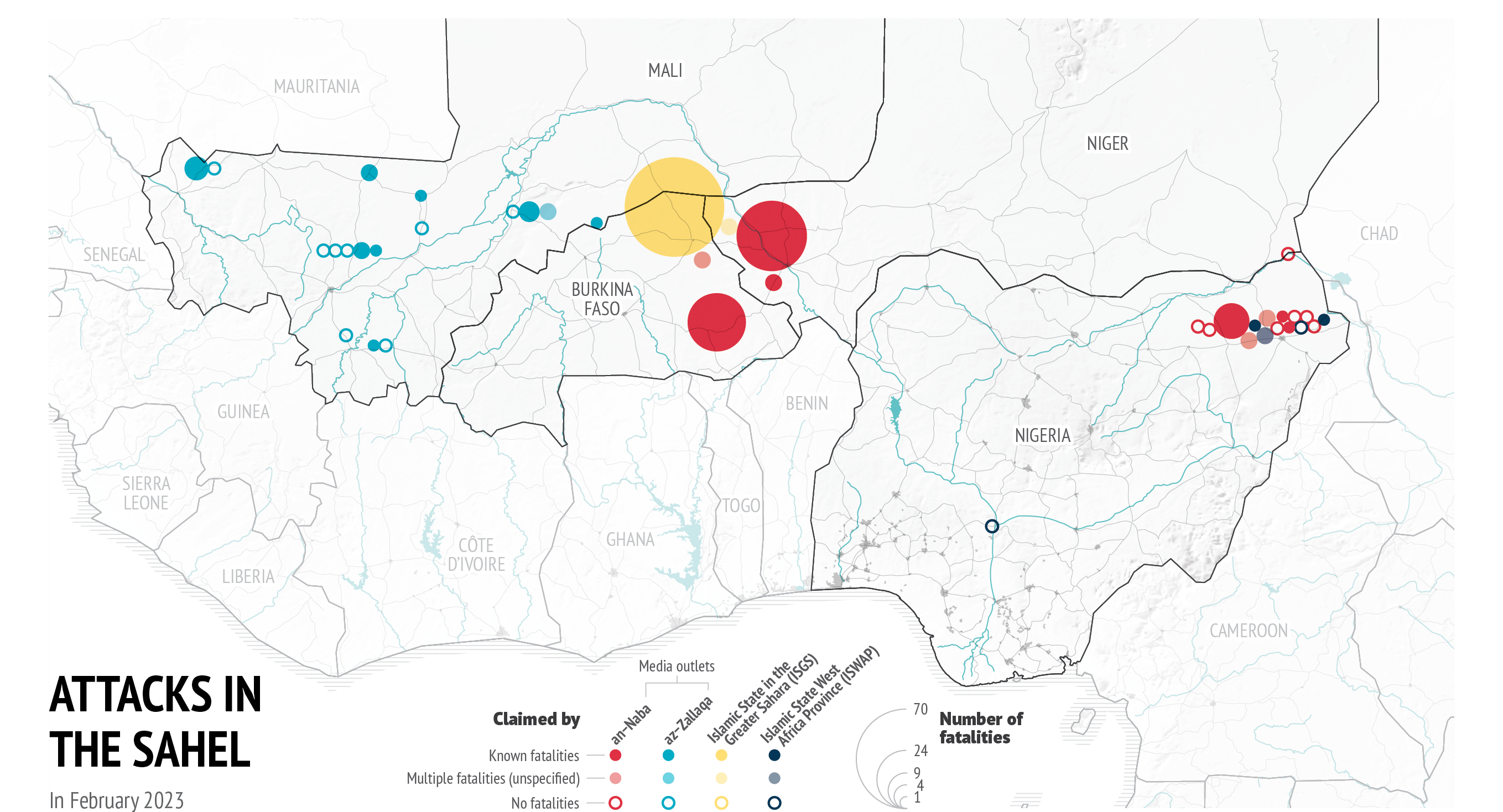

Data: Counter Extremism Project, 2023; European Commission, GISCO, 2023

Finally, Iran has opted for a flexible approach towards the Taliban regime since its takeover in 2021. It is defined by indispensable cooperation, non-confrontation and pragmatism. Most importantly, Shia Iran is wary of a Sunni extremist group holding the reins of power of a country with which it shares a border. Frequent visits of Taliban leaders to Tehran since the takeover in Afghanistan signal a deepening relationship between the two regimes (40). However, the Taliban takeover has intensified pre-existing tensions over drugs, water rights and refugees, endangering trade and creating new difficulties along the border (41). Tehran seems concerned that the situation in Afghanistan could lead to a proliferation of Sunni extremist groups at its border and is focused on avoiding such risks (42). The ISKP carried out an attack in 2022 on a Shiite shrine in Shiraz, located in the south of Iran (43). Overall, these attacks are aimed at delegitimising the Taliban as a government and security guarantor in the eyes of the international community while establishing ISKP as the dominant terrorist force in the region.

The transnational dimension

Afghanistan has changed drastically since 2001 and has not yet regained the status of a hotbed of terrorism that it once commanded. Yet the takeover by the Taliban in 2021 was interpreted positively in other safe havens around the globe which could be of interest to ISIS and al-Qaeda affiliated networks – including in Africa.

West Africa and the wider Sahel region have seen a significant increase in the activities of both al-Qaeda and ISIS-affiliated Islamist groups. Last year, ISKP’s November edition (44). This coincided with the official end of the French military Operation Barkhane in the Sahel at the beginning of November 2022, which left behind a security vacuum. Given this, the piece could be an indication that ISIS is planning an expansion into regions in which the al-Qaeda affiliate in Mali, Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal Muslimeen (JNIM) (45), currently is the dominant terrorist group. As of now, the main centre of gravity for ISIS in the region is the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), which is an offshoot of the Nigerian al-Qaeda affiliate Boko Haram and operates in the Lake Chad region. In Nigeria, ISWAP has since May 2021 succeeded in eliminating the then key leader of Boko Haram, Abubakar Shekau, and, in turn, managed to recruit a lot of his former followers, thereby aiming for the leadership role in the regional struggle (46). Furthermore, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), operating in Mali, remains the smaller ISIS affiliate in the region and operates as a subgroup of ISWAP (47). Almost half of the attacks carried out in the Sahel in February 2023 were claimed by ISWAP (48). Overall, it seems likely that a similar post-August 2021 ‘victory narrative’ (49) for the ISIS-affiliated networks will prevail widely across Africa and it is to be expected that the impact of ISIS-affiliated networks will increase in the near future.

It is worth noting that the withdrawal of the international forces and a reduction of engagement by the EU (50), as well as the takeover of power by the Taliban, are seen as victories for al-Qaeda by the group’s global sympathisers(51). This greater operational flexibility for al-Qaeda affiliates in West Africa has allowed both al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and the al-Qaeda coalition JNIM (52) to recruit more non-Arabs. This has led to a transcendence of the insurgents’ own national – and ethnic – boundaries by building powerful alliances with other Islamist terrorist groups from sub-Saharan Africa (53). This is in line with al-Qaeda’s strategy of building a network structure across multiple regions on a global scale. The group has not given up on its ambitions to carry out attacks in the West, which is evident in an article from its web magazine One Ummah released on 26 December 2022, highlighting the situation in Somalia where the local al-Qaeda affiliate, al-Shabaab, is becoming increasingly aggressive (54). Comparing the situation with the withdrawal of international forces from Afghanistan, the magazine ominously declared that ‘the war is not over (55).’ This underlines the growing global threat emanating from al-Qaeda and its regional-based affiliates.

Policy recommendations for the EU

The EU does not recognise the Taliban regime as the legitimate government in Afghanistan and since its takeover of power in August 2021 EU institutions have increased their efforts to mobilise existing instruments that address potential terrorist risks to EU internal security.

In September 2021, the EU Council endorsed the counterterrorism action plan on Afghanistan (56), which should serve as a roadmap for the maintenance of appropriate terrorism risk mitigation measures. More recently, an EU Council resolution from March 2023 has added to the EU’s ongoing roadmap (57). As outlined in the 2021 action plan, maintaining appropriate capacities for counterterrorism analysis within EU Member States is of particular importance. Rather than focusing on how best to maintain such capacities within each of the EU Member States, pooling of resources at the EU level, in particular when it comes to language capacities, should be contemplated to ease the resource pressure on each Member State.

Terrorist spillover effects towards the CARs are of particular concern, given the history of terrorist violence in this region. Therefore, increased EU counterterrorism engagement in Central Asia should be contemplated. This includes regular visits of the EU Counter-Terrorism Coordinator to enable an exchange of relevant information and analysis, as well as EU cooperation with the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) and Gulf countries. Additionally, strengthening the EU’s capacity to deal with current and future security threats emanating on the ground. This could most effectively be arranged by strengthening EU representation in Kabul by increasing the number of EU Counter-Terrorism Experts working at the mission, rather than by re-establishing EU Member States’ missions in the country. Having a single European presence in the capital would also reduce the increased security requirements due to the Taliban regime’s inability (or unwillingness) to secure diplomatic representations.

Furthermore, existing information exchange mechanisms with the UN, in particular with UNAMA, should be strengthened. As UN missions continue to operate in most parts of the country, this would further increase situational awareness. Given the heightened risk of aid diversion for terrorist purposes by the Taliban and large-scale money laundering operations in the country, regular exchange of information with UNAMA’s risk management unit, which is responsible for coordinating risk mitigation mechanisms among international donors, should be established (58). EU Member States should ensure that UNAMA and in particular its risk management unit is appropriately mandated and resourced.

As of September 2016, the EU can apply sanctions autonomously against ISIS/Da’esh and al-Qaeda and persons and entities that are associated with or support them. This instrument could be used to ensure that all current and emerging terrorist leaders and groups in Afghanistan are targeted by EU restrictive measures. Furthermore, the EU could encourage and support the submission of listing proposals by EU Member States of relevant individuals and entities in Afghanistan to the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 1267 (1999) 1989 (2011) and 2253 (2015) concerning ISIS/Da’esh, al-Qaeda and associated individuals, groups, undertakings and entities as well as the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1988 (2011) (focusing on the Taliban).

This should also involve the channelling of new information concerning already sanctioned individuals and entities to ensure the continued effectiveness of these global sanctions measures. To enable the more effective identification of the movement of individuals from and to Afghanistan, the pooling and exchange of already available information on individuals who have travelled or are liable to travel to Afghanistan would be an effective measure. This could be achieved via a special project at Europol and modelled along the already existing FTF project at INTERPOL.

Finally, the Taliban, al-Qaeda and its affiliates in Afghanistan as well as ISKP, use internet-based services, such as social media platforms and messenger services to propagate, communicate Terrorist Content Online Regulation (April 2021), the EU has significantly increased its ability to interact with internet service providers, including on terrorism-related content. Therefore, existing channels of communication with these internet service providers should be strengthened and their active participation in combating the misuse of their services should be increased.

Conclusion

In August 2021, the Taliban informed the world that ‘we do not want to have any problem with the international community (59).’ Yet, their takeover has altered regional dynamics and now poses a tangible threat to the region, while impacting the Taliban’s own external relationships with bordering countries. As this Brief has made clear, a focus on the increasing security risks that the resurgence of the Taliban entails for neighbouring states, particularly with regard to the proliferation of militant Islamist groups in the CARS, is imperative. These risks are posed not only by the Taliban itself but also by additional Islamist terrorist groups such as ISKP, TTP and ETIM, some of which operate with the Taliban’s acquiescence. This underlines the complexity and multi-layered nature of the security threat emanating from Afghanistan. The observations made in this Brief call for a targeted security response that includes the pooling of EU resources and enhanced cooperation across Member States, rather than leaving it to each Member State to deal with the threat on a national level. Furthermore, it is highly recommended that the EU work in tandem with EUROPOL when it comes to the use of the internet and digital means for the identification and tracking-down of FTFs.

References

* The Counter Extremism Project (CEP) is an international, non- profitmaking and non-partisan international policy organisation formed to combat the growing threat from extremist ideologies (https://www.counterextremism.com/).

1. See Grechyna, D., ‘Political instability: The neighbor vs. the partner effect’, Munich Personal RePEc Archive, June 2017 (https://mpra.ub.uni- muenchen.de/79952/1/mpra_paper_79952.pdf).

2. Al Jazeera, ‘Transcript of Taliban’s first news conference in Kabul’,17 August 2021 (https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/8/17/transcript-of- talibans-first-press-conference-in-kabul).

3. For a detailed description of each terrorist group mentioned in this Brief, see CEP’s research databases available at: https://www. counterextremism.com.

4. See: United Nations Security Council, ‘Resolution 1989, S/RES/1989 (2011)’, 17 June 2011 (https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/s/res/1989-%282011%29); United Nations Security Council, ‘Resolution 2253, S/RES/2253 (2015)’, 17 December 2015 (https://www.un.org/ securitycouncil/s/res/2253-%282015%29).

5. Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team, ‘Twelfth report, S/2021/486’, 1 June 2021 (https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/2053487/ S_2021_486_E.pdf); Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team, ‘Thirteenth report, S/2022/419’, 26 May 2022, para. 39 (https://www. ecoi.net/en/file/local/2073803/N2233377.pdf).

6. Ibid.

7. US Department of the Treasury, ‘Memorandum for Department of Defense Lead Inspector General,’ 4 January 2021 (https://oig.treasury. gov/sites/oig/files/2021-01/OIG-CA-21-012.pdf).

8. Steinberg, G., ‘Taliban regime: Effects on global terrorist organizations’, in The Taliban’s Takeover in Afghanistan – Effects on global terrorism, Counter Extremism Project and Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, December 2022, p.70 (https://www.counterextremism.com/sites/default/files/2023-01/ KAS-CEP%20Report_The%20Taliban%27s%20Takeover%20in%20 Afghanistan_Dec%202022.pdf).

9. Mehra, T. and Wentworth, M., ‘The rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan: Regional responses and security threats’, International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, 27 August 2021 (https://www.icct.nl/publication/ rise-taliban-afghanistan-regional-responses-and-security-threats).

10. Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team, ‘Thirteenth report,S/2022/419’, 15 July 2022, para. 74.

11. Afghanistan International, ‘Taliban issues 3000 passports to terrorists, says Tajik interior minister’, 19 October 2019 (https://www.afintl.com/ en/202210196971).

12. See: Bergen, P., ‘Opinion: Does the anti-Taliban resistance stand a chance?’, CNN, 30 August 2022 (https://edition.cnn.com/2022/08/30/ opinions/nazary-anti-taliban-resistance-afghanistan-bergen/index. html); Afghanistan International, ‘NRF announces guerrilla operations against Taliban in Afghanistan,’ 29 March 2023 (https://www.afintl. com/en/202303296531); Press Institute for the Study of War, ‘Taliban struggles to contain Afghan National Resistance Front’, 7 September 2022 (https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/taliban- struggles-contain-afghan-national-resistance-front).

13. One example is the armed clashes between two Taliban factions in July 2022. See: Glinksi, S., ‘Taliban wage war over coal in Northern Afghanistan’, Foreign Policy, 5 July 2022 (https://foreignpolicy. com/2022/07/05/taliban-afghanistan-coal-mining-resources- economy/).

14. Badgamia, N., ‘At least 10 killed, several injured in blast outside Kabul’s military airport: Reports’, WIO News, 1 January 2023 (https://www. wionews.com/middle-east/blast-outside-kabuls-military-airport- several-killed-multiple-injured-reports-548450); Gul, A., ‘Chinasays Kabul hotel attack Injured 5 Chinese nationals’, Voa, 13 December 2022 (https://www.voanews.com/a/isis-k-claims-attack-on-kabul- hotel-housing-chinese-nationals/6873906.html); Reuters, ‘Islamic State claims responsibility for attack on Pakistani embassy in Kabul,’ 4 December 2022 (https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/ islamic-state-claims-responsibility-attack-pakistani-embassy- kabul-2022-12-04/).

15. Schindler, H. and Fisher-Birch, J., ‘Afghanistan Terrorism Report December 2022 to January 2023’, Counter Extremism Project, 27 January 2023 (https://www.counterextremism.com/blog/afghanistan-terrorism- report-december-2022-january-2023).

16. United Nations Secretary General, ‘The situation in Afghanistan and its implications for international peace and security. Report of the Secretary-General’, A/75/634–S/2020/1182, 9 December 2020, p.5 (https://unama.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/sg_report_on_ afghanistan_december_2020.pdf).

17. ‘Afghanistan Terrorism Report December 2022 to January 2023’, op.cit.

18. Marty, F. J., ‘Is the Taliban’s campaign against the Islamic State working?’, The Diplomat, 10 February 2022 (https://thediplomat. com/2022/02/is-the-talibans-campaign- against-the-islamic-state- working).

19. United Nations Secretary General, ‘Fourteenth report of the Secretary- General on the threat posed by ISIL (Da’esh) to international peace and security and the range of United Nations efforts in support of Member States in countering the threat’, S/2022/63, January 2022, para. 33 (https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27- 4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/S_2022_63_E.pdf).

20. Safi, K., ‘Daesh In Afghanistan’, in The Taliban’s Takeover in Afghanistan – Effects on global terrorism, op.cit., p.46.

21. See: Watkins, A., Taliban Fragmentation: Fact, fiction and future, United States Institute of Peace, March 2020 (https://www.usip.org/sites/ default/files/2020-03/pw_160-taliban_fragmentation_fact_fiction_ and_future-pw.pdf); White, J. W., ‘Nonstate threats in the Taliban’s Afghanistan,’ Brookings, 1 February 2022 (https://www.brookings.edu/ blog/order-from-chaos/2022/02/01/nonstate-threats-in-the-talibans- afghanistan/).

22. Jadoon, A., Mines, A. and Sayed, A., ‘The evolving Taliban-ISK rivalry’, The Lowy Institute, 7 September 2021 (https://www.lowyinstitute.org/ the-interpreter/evolving-taliban-isk-rivalry).

23. The Soufan Center, ‘IntelBrief: Islamic State Khorasan remains a stubborn threat in Afghanistan’, 29 March 2023 (https://thesoufancenter. org/intelbrief-2023-march-29/); Yawar, M.Y., ‘Two Russian embassy staff dead, four others killed in suicide bomb blast in Kabul’, Reuters,5 September 2022 (https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/ afghan-police-report-suicide-bomb-blast-near-russian-embassy- kabul-2022-09-05/).

24. Radio Free Europe, ‘Uzbekistan rejects claim by Islamic State affiliate In Afghanistan over rocket assault’, 19 April 2022 (https://www.rferl. org/a/uzbekistan-islamic-state-afghanistan--rocket-assault/31810956. html); Radio Free Europe, ‘Taliban investigating report that Islamic State fired rockets into Tajikistan’, 8 May 2022 (https://gandhara.rferl.org/a/ afghanistan-islamic-state-tajikistan-rockets/31839638.html).

25. Congressional Research Services, ‘Taliban Government in Afghanistan: Background and Issues for Congress’, 2 November 2021, p.23 (https:// crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46955).

26. Kapur, R., Madadi, S. and Mulroy, M., ‘Pakistan-Afghan Taliban relations face mounting challenges’, Middle East Institute, 21 February 2023 (https://www.mei.edu/publications/pakistan-afghan-taliban- relations-face-mounting-challenges).

27. Masood, S., ‘Pakistan in talks With Taliban militants, even as attacks ramp up’, New York Times, 4 October 2021 (https://www.nytimes. com/2021/10/02/world/asia/pakistan-taliban-talks.html); Rehman, Z., ‘Islamabad deeply alarmed by rise in Pakistan Taliban terrorism’, Nikkei Asia, 28 September 2021 (https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International- relations/Afghanistan-turmoil/Islamabad-deeply-alarmed-by-rise-in- Pakistan-Taliban-terrorism).

28. Ahmed, A. S., ‘China is using U.S. “War on Terror” rhetoric to justify detaining 1 million people’, HuffPost, 3 December 2018 (https://www. huffpost.com/entry/china-is-justifying-its-biggest-human-rights- crisis-in-decades-with-made-in-the-usa-war-on-terror-rhetoric_n_5 bae375be4b0b4d308d2639c).

29. Nabil, R., ‘The Taliban takeover of Afghanistan: The Haqqani network and al-Qaeda’ in The Taliban’s Takeover in Afghanistan – Effects on Global Terrorism, op.cit., p.35.

30. Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team, ‘Twenty-ninth report, S/2022/83’, 3 February 2022 (https://digitallibrary.un.org/ record/3957081?ln=en).

31. Blumenthal, L., Purdy, C. and Bassetti, V., ‘Chinese investment in Afghanistan’s lithium sector: A long shot in the short term’, Brookings, 3 August 2022 (https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2022/08/03/ chinese-investment-in-afghanistans-lithium-sector-a-long-shot-in- the-short-term/); Pantucci, R., ‘Inheriting the storm: Beijing’s difficult new relationship with Kabul’, The Diplomat, 1 December 2022 (https:// thediplomat.com/2022/11/inheriting-the-storm-beijings-difficult-new- relationship-with-kabul/).

32. Kullab, S., ‘China eyes investment in Afghanistan’s Mes Aynak mines,’ The Diplomat, 28 March 2022 (https://thediplomat.com/2022/03/china- eyes-investment-in-afghanistans-mes-aynak-mines/).

33. Webber, L. and Valle, R., ‘Islamic State in Afghanistan seeks to recruit Uzbeks, Tajiks, Kyrgyz’, Eurasianet, 17 March 2022 (https://eurasianet. org/perspectives-islamic-state-in-afghanistan-seeks-to-recruit- uzbeks-tajiks-kyrgyz).

34. Schindler, H. and Fisher-Birch, J., ‘Afghanistan Terrorism Report July 2022’, Counter Extremism Project, 15 August 2022 (https://www. counterextremism.com/blog/afghanistan-terrorism-report-july-2022).

35. Umarov, A. and Murtazashvili, J. B., ‘What are the implications of Uzbekistan’s rapprochement with the Taliban?’, The Diplomat, 8 August 2022 (https://thediplomat.com/2022/08/what-are-the-implications-of- uzbekistans-rapprochement-with-the-taliban/).

36. Ibid.

37. Associated Press, ‘China strongly backs Afghanistan at regional conference’, The Diplomat, 31 March 2022 (https://thediplomat. com/2022/03/china-strongly-backs-afghanistan-at-regional- conference/); Gul, A., ‘Russia to host multilateral talks on Afghanistan November 16’, VOA, 10 November 2022 (https://www. voanews.com/a/russia-to-host-multilateral-talks-on-afghanistan- november-16/6828126.html).

38. Webber, L, and Valle, R., ‘Islamic State in Afghanistan looks to recruit regional Tajiks, inflict violence against Tajikistan’, The Diplomat, 29 April 2022 (https://thediplomat.com/2022/04/islamic-state-in-afghani- stan- looks-to-recruit-regional-tajiks-inflict-vi- olence-against-tajikistan/).

39. Wright, R., ‘U.S. retaliation for the Kabul bombing won’t stop ISIS or end terrorism,’ The New Yorker, 27 August 2021 (https://www.newyorker.com/ news/daily-comment/us-retaliation-for-the-kabul-bombing-wont- stop-isis-or-end-terrorism).

40. See for example: Iran International, ‘Taliban FM describes Iran visit as positive, reportedly meets opposition,’ 1 September 2022 (https://www. iranintl.com/en/202201098366).

41. Farr, G., ‘Iran and Afghanistan: Growing tensions after the return of the Taliban,’ E International Relations, 23 August 2022 (https://www.e-ir. info/2022/08/23/iran-and-afghanistan-growing-tensions-after-the- return-of-the-taliban/).

42. Farid Tookhy, A., ‘Iran’s response to the Taliban’s comeback in Afghanistan,’ United States Institute of Peace, August 2022 (https:// www.usip.org/sites/default/files/Afghanistan-Peace-Process_Irans- Response-Talibans-Comeback-Afghanistan.pdf).

43. Hafezi, P., ‘Islamic State claims Iran shrine attack, Iran vows response,’ Reuters, 27 October 2022 (https://www.reuters.com/world/middle- east/riot-police-deploy-iranian-cities-people-gather-aminis- memorial-2022-10-26/).

44. Schindler, H. and Fisher-Birch, J., ‘Afghanistan Terrorism Report November 2022’, Counter Extremism Project, 20 December 2022 (https:// www.counterextremism.com/blog/afghanistan-terrorism-report- november-2022).

45. The group has in recent years expanded its operations to neighbouring countries such as Burkina Faso, Niger, and Senegal.

46. Anyadike, O., ‘Quit while you are ahead: Why Boko Haram fighters are surrendering,’ The New Humanitarian, August 12, 2021 (https:// www.thenewhumanitarian.org/analysis/2021/8/12/why-boko-haram- fighters-are-surrendering); International Crisis Group, ‘After Shekau: Confronting jihadists in Nigeria’s North East,’ 29 March 2022 (https:// www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/nigeria/after-shekau- confronting-jihadists-nigerias-north-east).

47. Thomson, J., ‘Examining extremism: Islamic State in the Greater Sahara’, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 22 July 2021 (https://www.csis.org/blogs/examining-extremism/examining- extremism-islamic-state-greater-sahara).

48. Ostaeyen, P., ‘CEP-KAS: Sahel Monitoring February 2023’, Counter Extremism Project, 8 March 2023 (https://www.counterextremism.com/ blog/cep-kas-sahel-monitoring-february-2023).

49. See: Pantucci, R., and Basit, A., ‘Post-Taliban takeover: How the global jihadist terror threat may evolve’, Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses, Vol. 13, No 4, 2021, p.5.

50. For example, through the suspension of training missions in Mali (EUTM). See: Euractiv, ‘EU leaves military training in Mali suspended, stops short of ending mission’, 18 May 2022 (https://www.euractiv.com/ section/africa/news/eu-leaves-military-training-in-mali-suspended- stops-short-of-ending-mission/).

51. ‘Taliban regime: Effects on global terrorist organizations’, op.cit., p.69.

52. It is worth noting that AQIM is a member of JNIM.

53. ‘Taliban regime: Effects on global terrorist organizations’, op.cit., pp.73- 75.

54. ‘Afghanistan Terrorism Report December 2022 to January 2023’, op.cit.

55. Ibid.

56. European Council, ‘Timeline: the EU’s response to terrorism’ (https:// www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/fight-against-terrorism/history- fight-against-terrorism).

57. EU Council, ‘Council conclusions on Afghanistan,’ 20 March 2023 (https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-7264-2023-INIT/ en/pdf).

58. Schindler, H., ‘The Taliban regime: Regional and international financial risks’, in The Taliban’s Takeover in Afghanistan – Effects on global terrorism, op.cit., pp. 51-59.

59. Al Jazeera, ‘Transcript of Taliban’s first news conference in Kabul,’17 August 2021.