You are here

A like-minded partner?

Introduction

In late April 2022, European Commission President von der Leyen embarked on an official visit to India in an endeavour to boost EU-India relations. The main focus of the visit was the resumption of negotiations for a free trade agreement (FTA) and exploring options for an India-Europe Trade and Technology Council, the EU’s only second such council with a foreign partner (the other being the United States). The following week, in early May 2022, Prime Minister Modi visited Germany, Denmark and France successively. In Berlin, he held inter-governmental consultations with new German chancellor Scholz; in Copenhagen, he attended the second India-Nordic Summit with the prime ministers of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden, and in Paris, he met with newly re-elected President Macron. This flurry of diplomatic activity reflected the growing density of India’s relations with the EU collectively and with various European states.

These high-level interactions took place in a context of heightened tensions between Europe and Russia over the war in Ukraine. Interestingly, despite their growing ties, India and its European partners are far from being aligned on this crucial issue. By contrast with the EU and most European states, India has refused to condemn Russia’s ‘special military operation’ and carefully avoided naming Russia as an aggressor. It also abstained from voting on the resolutions brought by Western countries against Russia in UN bodies, including the one on 7 April 2022, which suspended Russia from the UN Human Rights Council. India has not joined its European partners in sanctioning Moscow either. Its approach has been to emphasise dialogue and diplomacy to address the conflict in Ukraine.

Following its refusal to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, India attracted even more diplomatic attention. Leaders from Australia, Japan, the United Kingdom, the United States and the EU interacted with New Delhi in the hope of influencing its diplomatic position, to no avail. Analysts have amply described the considerations driving India’s cautious position, including its dependence on Russian military equipment, energy needs, fear of a Sino-Russian rapprochement, as well as its policy of strategic autonomy and historical stance of non-interference in domestic affairs and in defence of state sovereignty. These reasons are no doubt valid. Yet, India’s refusal to condemn Russia’s violation of international law questions the assumptions underlying the EU’s engagement with this country.

Much of the EU’s engagement with India has been based on the notion that it shares common values with this country as well as the common goal to uphold a rules-based international order (1). The idea of shared values has featured prominently in the EU-India narrative, even more since the two sides reinvigorated their strategic partnership in the early 2020s. Significantly, the joint statement issued at the 2021 EU-India summit starts with the following assertion: ‘The meeting today highlighted our shared interests, principles and values of democracy, freedom, rule of law and respect for human rights, which underpin our Strategic Partnership’ (2).

But do the EU and India really share the same democratic values today? To answer this question, this Brief examines the deep domestic transformations induced by the rise to power of Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) since 2014.

India's democratic backsliding

The Hindu nationalist agenda

Modi and the BJP are the political incarnations of Hindu nationalism, an ideology that regards India as the holy land of the Hindus and promotes the unity and supremacy of the Hindu nation, often at the expense of the Muslim and Christian minorities of the country. The mother organisation of the Hindu nationalist movement is not the BJP, but the RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or National Volunteer Organisation), a cultural association, which serves as its ideological ballast and claims to have 5 to 6 million active members. With its paramilitary ethos, the RSS aims at regenerating the Hindu community to make it more disciplined and stronger as a nation. It is considered hardline because of its involvement in communal violence (it was banned in 1948 after one of its former members assassinated Mahatma Gandhi, then in 1975 during the Emergency and, finally in 1992 following an assault on and destruction of a mosque in Ayodhya). Modi himself rose through the ranks of the RSS before entering politics. In fact, 41 out of the 66 ministers of his first government (2014-1019) had an RSS background, as well as 38 out of the 53 ministers of his second government (since 2019) (3).

Modi’s second government has been especially focused on pushing the Hindu nationalist agenda. In August 2019, it scrapped Article 370 of the Constitution, which guaranteed the autonomy of Jammu and Kashmir (J-K) as well as a limited degree of devolution of political power. This was a long-held goal of the Hindu nationalist ideologues, for whom the special constitutional status of J-K, India’s single Muslim-majority state, embodied the supposedly exorbitant privileges given to the Muslim minority by India’s secular state. In the two months that followed the revocation of art. 370, a total of 177 political leaders were detained in Kashmir (4). A near-complete internet blackout was imposed on the newly formed Union Territory of J-K for nine months (5).

The idea of shared values has featured prominently in the EU-India narrative.

The Modi government has also achieved the long-held goal of building a temple dedicated to Ram (one of the most worshipped gods of the Hindu pantheon) in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh (UP). The issue of the Ram temple has been the flagship theme of Hindu nationalism for decades. In the late 1980s, the BJP became a powerful electoral force in North India by organising a mass campaign (with the help of the RSS) to destroy a mosque in Ayodhya that was supposedly built on a temple dedicated to Ram.

Following the destruction of the mosque by Hindu extremists in late 1992, the issue was stalled in legal battles for three decades, but the Hindu nationalist movement maintained its campaign to build the Ram temple. In late 2019, the Supreme Court eventually delivered a verdict favourable to the temple’s construction. Significantly, in August 2020, Prime Minister Modi performed a ritual for the laying of the temple’s foundation stone, thus signalling his personal association with this major victory of Hindu nationalism.

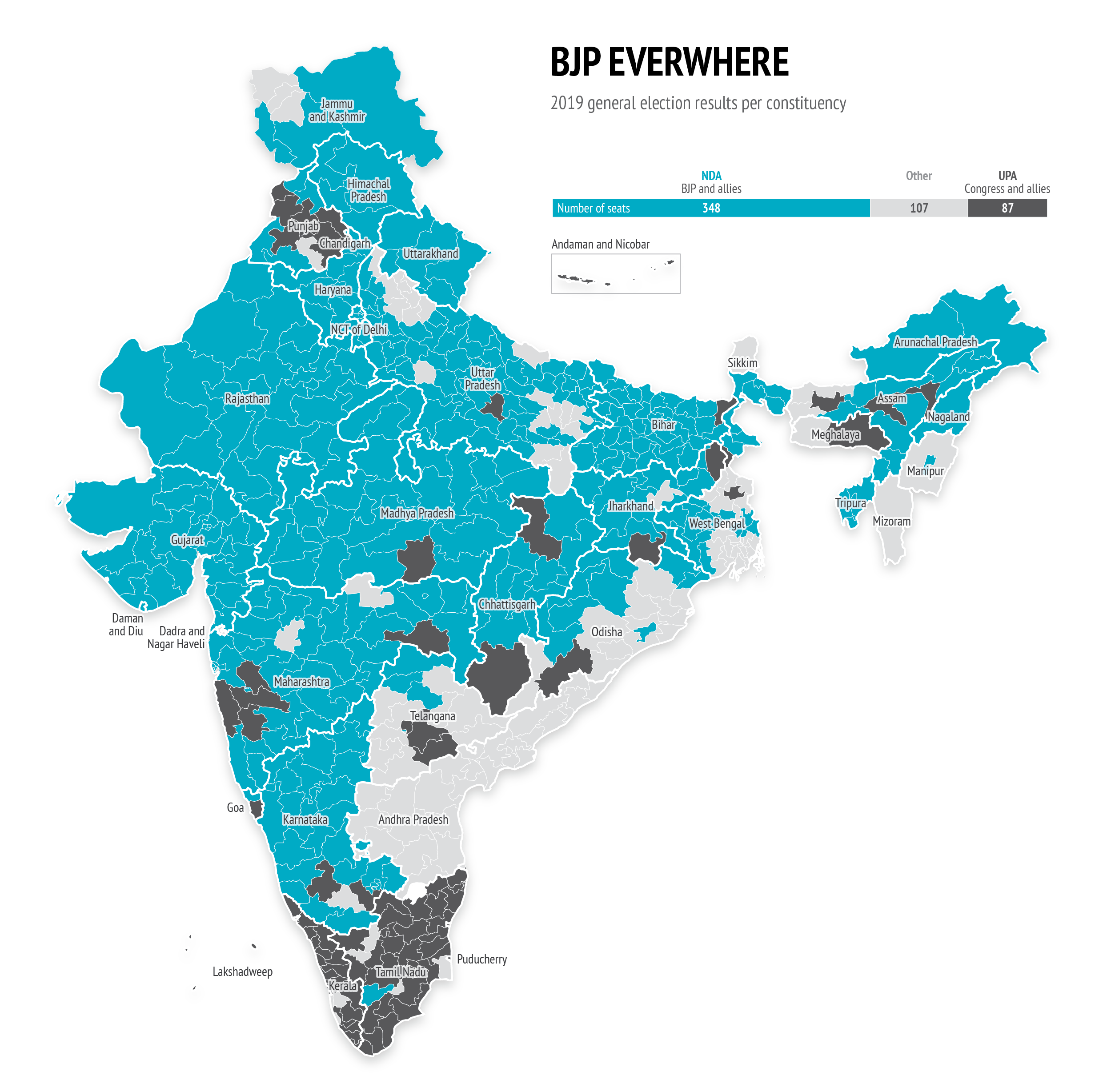

Data: Reuters, 2019; GADM, 2022

Another victory was the passage in Parliament of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA) in December 2019. This law, which allows all undocumented migrants from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan, except for Muslims, to apply for Indian citizenship, introduces a religious criterion to the definition of Indian citizenship for the first time. It also makes the Muslims in India a special category in law, potentially paving the way to legally transforming them into citizens with lesser rights, especially in terms of access to justice. Because of its discriminatory nature, the CAA ignited massive opposition, first initiated by students in the university campuses of Uttar Pradesh and Delhi, and then followed by nationwide protests, with the predominant, but not exclusive, participation of Indian Muslims, including many women.

Anti-minority violence

Violence against Muslims, scheduled castes and other minorities is not a new phenomenon in India. But the frequency of such violence, as well as its social and political acceptability, have significantly increased since 2014. Muslims (and the lowest Hindu castes to a lesser extent) have been exposed to recurring attacks in the name of alleged crimes such as ‘love jihad’ and cow slaughter (6). The perpetrators are well-known entities like the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), a mass organisation led by right-wing religious chiefs and its paramilitary youth wing, the Bajrang Dal, both of which embody the most extreme expression of the Hindu nationalist movement, as well as vigilante groups, which have mushroomed since the mid-2010s (7).

These anti-minority attacks have been encouraged by a permissive context, where the perpetrators enjoy near impunity. More often than not, the police are paralysed when anti-minority violence erupts; in some cases, it has been found to protect the aggressors rather than the victims. For some vigilante activists, committing anti-Muslim violence can in some instances be seen as a springboard to a political career. This is illustrated by the stellar trajectory of Yogi Adityanath, a firebrand Hindu cleric who led a violent militia ‘for the protection of the Hindus’ in Uttar Pradesh (UP), had several cases of anti-Muslim violence against him and became a member of Parliament in 1998 at the age of 26 (8). In 2017, when the BJP won the state Assembly election in UP, India’s most populous state, he was selected by Modi to be the Chief Minister.

Since he has led the UP government, Adityanath has become the ‘rising star’ of Hindu nationalism and has even been considered a potential successor to Modi. As a result, Adityanath has inspired other BJP Chiefs Ministers, who have seen his model of governance as the best way to remain in the race for taking over from Modi in the future. An example of this phenomenon of competitive extremism can be found in Shivraj Singh Chauhan and Basavaraj S. Bommai, respectively Chief Ministers of the Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka governments (9). Both have emulated Adityanath and promoted anti-minority policies in their state. More generally, BJP-ruled states have been prone to introducing anti-minorities laws. Since 2017, seven BJP-ruled states – Jharkhand, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, UP and Madhya Pradesh, Haryana and Karnataka – have passed anti-conversion laws (that criminalise conversion to Islam or Christianity, especially in the context of interfaith marriage).

Prime Minister Modi’s reluctance to condemn the violence committed by Hindu extremist groups is interpreted as a free pass by them. At the same time, rival political parties at the state and central levels have been hesitant in speaking up for minorities, including Muslims. Two parties on the centre-left of the political spectrum, the Indian Congress Party and Aam Aadmi Party (AAP or Common Man’s Party), for instance, have been tempted to try and win away sections of the pro-Hindu vote from the BJP by emphasising their own cultural Hindu identity (10).

Restricting civic freedoms

Under BJP rule, free speech has come under growing pressure. Independent media houses and journalists critical of the government have been exposed to legal intimidation. In 2021, Dainik Bhaskar, India’s largest-circulated newspaper, was subjected to a tax raid, after its in-depth coverage of the government’s mismanagement of the Covid-19 pandemic (11). That same year, The Caravan magazine was targeted by multiple investigations by state police forces after covering the farmers’ protests against the agricultural reform implemented by the Modi government. The magazine’s Twitter account was also suspended, at the request of the government (12). In Jammu and Kashmir (J-K) and Uttar Pradesh (UP), the situation has become particularly difficult for journalists. In J-K, at least 35 journalists were subjected to ‘police interrogation, raids, threats, physical assault, restrictions on freedom of movement, or fabricated criminal cases for their reporting’ between the abrogation of article 370 of the Constitution (August 2019) and early 2022 (13). In UP, 66 journalists have been charged with criminal cases by the state authorities, and another 48 have been ill-treated since Adityanath was appointed Chief Minister (2017) (14).

The Modi government has also resorted to repressive tools such as the Sedition Law, which dates back to the colonial era, and the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA), which is a counter-terrorism law (15). UAPA and sedition cases respectively registered a 33 % and 165 % rise between 2016 and 2019 (16). Cases have generally surged in the context of major protest movements against the BJP government at the centre and in the states, such as those against the Citizen Amendment Act or the farmers’ protests of late 2020. In this regard, the United Nations Special Rapporteurs noted in March 2021: ‘we are particularly concerned by indications that a rising number of peaceful protests, opposition politicians, students, journalists, authors and academics, among others have been charged under these laws [i.e. sedition law and anti-terrorism legislation], due the ambiguity and broadness of their provisions (…)’ (17).

Moreover, the Modi government amended the UAPA in 2019 to expand the qualification of terrorism to individuals (and not just to organisations as was originally the case). Regarding this amendment, the UN special rapporteurs noted in a communication in 2020 that it is not compliant with the set international standards of counter-terrorism legislation and contravenes several articles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights. The rapporteurs also underlined that ‘as enacted, the amendment raises serious concerns regarding the designation of individuals as “terrorists” in the context of ongoing discrimination directed at religious minorities, human rights defenders and political dissidents, against whom the law has been used’ (18).

In addition to being threatened by draconian laws, peaceful protesters against the Citizen Amendment Act have been exposed to violence (19). In northeast Delhi, protesters who had occupied a road since December 2019 clashed with a Hindu mob on 23 February 2020. The clash led to three days of communal violence in the capital city. Investigation by independent media such as The Caravan showed that the RSS, BJP and Bajrang Dal prepared the ground for an outbreak of violence by stirring up hatred against anti-CAA protesters (20). The riots left 53 people dead, 40 of whom were Muslims. Justice S. Muralidhar from the Delhi High Court (HC) blamed the police for its inaction during the riots. He was immediately transferred to the Punjab and Haryana HC (21).

The Modi government has instrumentalised the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA) to control NGOs and non-profit organisations. The FCRA was adopted in 2010 under the Congress-led government of Manmohan Singh, to prohibit the receipt of foreign funds ‘for any activities prejudicial to the public interest’. In 2020, the Modi government amended the FCRA to further tighten the conditions under which NGOs can receive and use foreign donations. As many as 16 754 NGOs have been stopped from accessing foreign funding since 2014, according to the Ministry of Home Affairs (22). In 2020, Amnesty International suspended its operations in India, as its accounts were frozen by the government for allegedly circumventing the FCRA. Oxfam India also lost its FCRA registration, on the grounds that it hurt public interest.

The Modi government and external criticism

India's low rankings on democracy indices

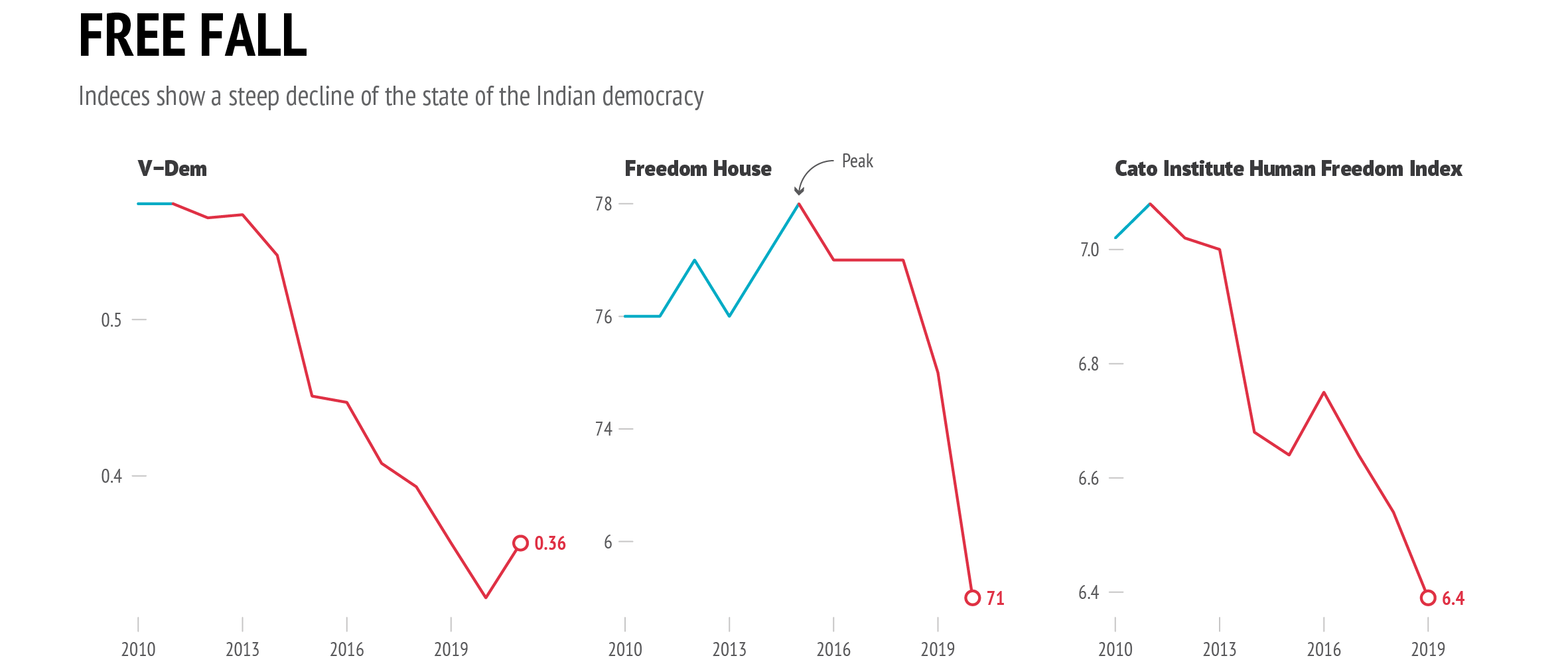

India’s democratic backsliding has been measured by various international watchdogs. While these assessments do have caveats and can be criticised (23), their relevance lies in the fact that they all point to a clear decline in democracy since Modi and the BJP assumed power in 2014 (see the graph on page 3).

For instance, V-Dem Institute, an independent research institute based in Sweden, downgraded India from the category of an electoral democracy to that of an electoral autocracy in 2019 and slotted India among the Top 10 ‘autocratising’ nations in 2022 (24). Similarly, in 2021, US government-funded NGO Freedom House downgraded India from ‘free’ to ‘partly free’ for cracking down on ‘expressions of dissent by the media, academics, civil society groups, and protesters’ (25). India’s rankings and/or scorings also plummeted in The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index and the Cato Institute’s Human Freedom Index. In December 2020, the Cato Institute gave India a score of 6.43, which was lower than the index’s average human freedom rating of 6.93. With respect to press freedom specifically, Reporters Without Borders ranked India 142nd out of 180 countries in its Press Freedom Index in 2020 and 2021, and further downgraded it to 150th in 2022.

The Modi government has responded to these plummeting indices with a combination of denial and denigration. It has depicted these assessments as distorted and biased. Foreign affairs minister Jaishankar, who has been at the forefront of the rebuttal, suggested they reflected a Western sense of superiority, if not neocolonialism (26). Similarly, in response to RSF’s low ranking of India in 2020, the Modi government set up the ‘Index Monitoring Cell’ (IMC), a committee of 11 government employees and 4 journalists, mandated to find ways to improve India’s ranking on the freedom of press index. In late 2020, the IMC submitted a draft report, with a set of recommendations. But rather than addressing the issue of the government’s attacks on press freedom, the draft concluded that India’s poor ranking resulted from ‘Western bias’ (27).

Data: V−Dem Institute, V−Dem, 2022; Freedom House, Freedom in the World, 2022; Cato Institute, Human Freedom Index, 2022

The Modi government has also sought to influence some Western-based democracy watchdogs. In 2021, it reached out to the Economist Intelligence Unit to seek clarification on its classification of India as a ‘flawed democracy’ and reportedly offered to provide its own data for the EIU’s Democracy Index ratings (28). All this shows that the BJP-led government reduces the meaning of democracy to the holding of regular elections – which generally remain free and fair – at the expense of other dimensions, such as the protection of civic freedoms. These differing perspectives on the nature of democracy could become a matter of contention between India and its Western partners.

India's reaction to the concerns of its partners

India may still be considered a democracy in many respects (with free and fair elections, numerous active opposition parties, instances of effective mass protest movements against government policies as illustrated by the farmers’ protests). Nevertheless, a degree of democratic backsliding is observable and has alarmed different states and multilateral organisations, and some of them have openly expressed their concerns. More often than not, the Indian government has retorted with denial or contempt. This is not entirely new. India has traditionally been very sensitive to foreign comments on its domestic affairs. But its superciliousness has reached new levels since 2014, as if the Modi government’s intolerance of criticism at the domestic level had somewhat spilled over into its reactions at the international level. In 2020 and 2021 for instance, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet repeatedly conveyed her concerns about India’s overuse of repressive laws such as the FCRA (29). The Modi government merely responded that such remarks were ‘unwarranted’.

India’s reactions to criticism from Muslim countries and organisations have been harsher. Angry words were exchanged with Bangladesh, Malaysia, Turkey and Indonesia when they criticised India’s treatment of its Muslim minority. Delhi also had a diplomatic spat with Iran (30). Similarly, when the Organization of Islamic Countries (OIC) condemned the Delhi riots of February 2020, the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) spokesperson Raveesh Kumar dismissed the statements of this organisation as ‘factually inaccurate’, ‘selective’ and ‘misleading’ (31). On 14 February 2022, the OIC again requested India to guarantee the safety of its Muslim community (32). In return, the MEA accused the OIC of acting out of anti-India prejudice and of having been ‘hijacked by vested interests [read Pakistan] to further their nefarious propaganda against India’ (33).

The latent malaise of many Muslim countries regarding India’s treatment of its Muslim minority transformed into an open crisis in June 2022 after two spokespersons of the BJP made controversial remarks about Prophet Muhammad. At least 20 Islamic countries and organisations, including close partners from the Gulf such as Kuwait, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, strongly protested against the derogatory comments. Faced with such a backlash, the BJP eventually removed its two officials.

India’s democratic backsliding may entail a reputational cost.

The Modi government has equally resented criticism from its Western partners. It denounced as ‘factually inaccurate’ and ‘misleading’ the concerns expressed by leading figures in the United States – including in the House Foreign Affairs Committee, the US Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) and Democrat presidential candidate Bernie Sanders – about the violence in Delhi of February 2020. MEA spokesperson Raveesh Kumar also commented that such concerns ‘appear[ed] to be aimed at politicizing the issue’ (34). When the European Parliament moved to file six draft resolutions on the revocation of the autonomy of J-K and the CAA, in January 2020, Indian Vice President Venkaiah Naidu remarked that such initiatives were based on ‘inadequate knowledge’ and ‘insufficient understanding’, in addition to being ‘totally uncalled for and unwarranted’ (35).

A challenging but courted strategic partner

India’s democratic backsliding may entail a reputational cost, with many ‘Western’-based news outlets reporting on the corrosion of its civic freedoms and religious pluralism. For a well-informed and progressive international audience, Prime Minister Modi’s ambition to project India as a ‘Vishwa guru’ (mentor to the world) may sound at odds with the reality of his domestic governance (36).

Notwithstanding a few short-lived diplomatic spats, India’s illiberal turn has so far had a limited diplomatic and strategic cost. Indeed, many states, including Western countries and liberal democracies, have continued to woo India as a valuable and ‘like-minded’ partner. For instance, the Biden administration has sought to enhance relations with India, despite having pledged to strengthen democracy at home and abroad. In so doing, it has ignored the recommendations of USCIRF, an independent and bipartisan federal government entity, which has suggested that the US State Department designate India as a ‘Country of Particular Concern’ since 2020. The United States’ closest allies, such as Australia and the United Kingdom, have taken the same approach. And the EU and its Member States have been no exception to this trend. The EU has reinforced its relations with India in recent years under the Connectivity Partnership signed in May 2021 as well as its ‘Indo-Pacific strategy’.

One reason explaining this large degree of tolerance from its Western partners is that India is seen in a larger context of democratic decline the world over, where even long-established democracies such as the United States, the United Kingdom and France have experienced a phenomenon of democracy fatigue. Additionally, India is mostly seen against a background of growing anxiety about China. When compared to China, India is not only perceived as a desirable partner but also as a potential bulwark and indispensable stakeholder to help stabilise the global order. In this respect, Washington’s and Europe’s anxiety about China has so far played to India’s advantage. And the Modi government has fully exploited this situation to push its Hindu nationalist agenda at home and maintain India’s historical non-alignment policy, characterised as ‘multi-alignment’ or ‘strategic autonomy’.

The same logic has applied to India’s pragmatic pursuit of its interests abroad and its refusal to take sides in the confrontation between the EU and Russia over Ukraine. India has substantially increased its import of discounted crude oil from Russia and, in so doing, it has ignored the disquiet expressed by its Western partners (37). And yet, despite their frustration with India’s uncooperativeness, the EU and the United States, and its Indo-Pacific allies, such as Japan and Australia, have conceded that New Delhi has particular constraints pertaining to its energy and food security, which account for its close ties to Russia.

Recommendations: How to engage India?

The EU has so far maintained its engagement policy with India despite their divergences over Russia. India is simply too important to be neglected or, worse, alienated, and the EU has to continue engaging this rising power. In a context where China challenges the liberal rules-based order, the EU needs major partners such as India by its side. Its objective should be to further align India’s strategic and economic interests with its own and to encourage India to be a leading pillar of a rules-based order. At the same time, the EU has to acknowledge India’s unique approach to international affairs as well as its massive development needs, including for fuels, fertilisers and technology.

The EU has many tools – including the newly formed Trade and Technology Council and FTA negotiations – to try and bridge the gap with India on important international and development issues. Moreover, the EU and some states such as France, Germany and Italy could take the opportunity of India’s first-ever presidency of the G20 (starting in December 2022) to strengthen coordination with New Delhi on such crucial issues as the clean energy transition and climate financing, as well as digital public infrastructure and tech-enabled development. As host of the G20 Summit in September 2023, India will want this major event to be a success and the EU should bring its full support to demonstrate the relevance of the G20 in an increasingly polarised world. It could join forces with India in an effort to strengthen multilateral institutions (including to reform the governance of multilateral financial institutions). It could also encourage India to play a potential mediating role with Russia to reduce the risks of military escalation over the Ukraine war.

While being ambitious and flexible in engaging India, the EU should remain clear-eyed about its democratic backsliding. This is the thorniest issue in the partnership as India is particularly sensitive to foreign criticism of its domestic politics and its democratic backsliding is unlikely to be reversed over the short-term (38). However, the EU should strive to remind the BJP-led government that democracy requires not only to hold free and fair elections but also to protect civic freedoms, pluralism and minorities. In so doing, the EU should further engage with – and give visibility to – dissenting voices, advocacy groups and NGOs that defend the secular and liberal institutions of India.

References

1. The concept of a ‘rules-based international order’ does not have a clear-cut, consensual meaning. At the very least, it can be defined as an international system in which states commit to abide by a common set of rules, norms and laws, with the UN at its centre. As articulated by the EU or the US, the concept has encompassed a more ambitious agenda of promoting democracy, respect for human rights, free and open, as well as fair, trade, basic principles of international law, and the rule of law. For the EU approach, see: European Commission, High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council on strengthening the EU’s contribution to rules-based multilateralism, JOIN (2021) 3 final, 17 February 2021 (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ en_strategy_on_strengthening_the_eus_contribution_to_rules- based_multilateralism.pdf).

2. Joint Statement: EU-India leaders’ meeting, 8 May 2021 (https://www. consilium.europa.eu/media/49523/eu-india-leaders-meeting-joint- statement-080521.pdf).

3. Pandey, N. and Arnimesh, S., ‘RSS in Modi govt in numbers — 3 of 4 ministers are rooted in the Sangh’, The Print, 27 January 2020 (https:// theprint.in/politics/rss-in-modi-govt-in-numbers-3-of-4-ministers- are-rooted-in-the-sangh/353942/).

4. Bhardwaj, A., ‘Only one from BJP among 177 politicians arrested in Kashmir after Article 370 move’ , The Print, 26 November, 2019 (https:// theprint.in/india/only-one-from-bjp-among-177-politicians-arrested- in-kashmir-after-article-370-move/326491/).

5. As per the decision taken in August 2019, the former J-K state was divided into the Union Territories of Ladakh and (truncated) J-K, ruled by the Centre.

6. ‘Love Jihad’ refers to the fantastical notion that Muslims try to increase their share of the population by seducing and converting Hindu women.

7. Vigilante groups are formed by ordinary citizens who take it upon

8. Sharma, S., ‘They paid a price for Adityanath’s hate speech – and now have fallen silent’, Scroll, 29 April 2017 (https://scroll.in/article/835416/ they-paid-a-price-for-adityanaths-hate-speech-and-now-have- fallen-silent).

9. Pandey, A.K., ‘Welcome to the Bulldozer Republic’, Newsclick, 21 April 2022 (https://www.newsclick.in/Welcome-to-the-Bulldozer-Republic).

10. The AAP was created in late 2012 as a follow-up to a massive anti- corruption movement. It runs the government of Delhi and Punjab.

11. Shih, G. and Masih, N., ‘Top Indian newspaper raided by tax authorities after months of critical coverage’, The Washington Post, 22 July 2021 (https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/india-modi- press-raid/2021/07/22/facbc01a-eabd-11eb-84a2-d93bc0b50294_story. html).

12. ‘Indian police arrest, investigate journalists covering farmers’ protests’, Committee to Protect Journalists, 1 February 2021 (https://cpj. org/2021/02/indian-police-arrest-investigate-journalists-covering- farmers-protests/); Kaushik, M. and Penkar, A., ‘Reporting is not a crime. So why has India’s government charged our magazine?’, Open Democracy, 5 February 2021 (https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/ reporting-not-crime-so-why-has-indias-government-charged-our- magazine/).

13. Reporters Without Borders, ‘India: Media freedom under threat’, 3 May 2022 (https://rsf.org/en/india-media-freedom-under-threat); Human Rights Watch, ‘India: Kashmiri journalist held under abusive laws’, 8 February 2022 (https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/02/08/india-kashmiri- journalist-held-under-abusive-laws).

14. Mehta, A., ‘Journalists In UP face a flood of criminal cases from Yogi Adityanath’s govt’, Article 14, 8 March 2022 (https://article-14.com/ post/journalists-in-up-face-a-flood-of-criminal-cases-from-yogi- adityanath-s-govt-6226b5db6bb7b ); Reporters Without Borders, ‘India: Media freedom under threat’, op.cit.

15. Sedition is defined in the Indian Penal Code as any speech or writing, or form of visible representation, which brings the government either into contempt or hatred or may excite disaffection towards the government or attempts to do so.

16. Purohit, K., ‘Our new database reveals rise in sedition cases in the Modi era’, Article 14, 2 February 2021 (https://www.article-14.com/post/our-new-database-reveals-rise-in-sedition-cases-in-the-modi-era); Lakhdhir, L. and Bajoria, J. ‘Sedition law: Why India should break from Britain’s abusive legacy’, Human Rights Watch, 18 July 2022 (https:// www.hrw.org/news/2022/07/18/sedition-law-why-india-should-break- britains-abusive-legacy); Verghese, L., ‘NCRB 2019 data shows 165% jump in sedition cases, 33% jump in UAPA cases under Modi govt’, The Print, 12 October 2020 (https://theprint.in/opinion/ncrb-2019-data- shows-165-jump-in-sedition-cases-33-jump-in-uapa-cases-under- modi-govt/521861/).

17. OHCHR, Communication report of special procedures India JAL IND 2/2021, 9 March 2021 (https://spcommreports.ohchr.org/TMResultsBase/DownLoa dPublicCommunicationFile?gId=26053).

18. OHCHR, Communications report of special procedures India JOL IND 7/2020, 6 May 2020 (https://spcommreports.ohchr.org/TMResultsBase/DownLoadP ublicCommunicationFile?gId=25219).

19. ‘India: Citizenship Act protesters tortured in detention - new testimony’, Amnesty International UK, 16 January 2020 (https://www.amnesty.org. uk/press-releases/india-citizenship-act-protesters-tortured-detention- new-testimony).

20. Singh, P. and John, A., ‘Crime and prejudice: The BJP and Delhi police’s hand in the Delhi violence’, The Caravan Magazine, 1 September 2020 (https://caravanmagazine.in/politics/the-bjp-and-delhi-police-hand-in-the-delhi-violence); ‘India: end bias in prosecuting Delhi violence’, Human Rights Watch, 15 June 2020 (https://www.hrw. org/news/2020/06/15/india-end-bias-prosecuting-delhi-violence); Gettleman, J., Raj, S. and Yasir, S., ‘The roots of the Delhi riots: A fiery speech and an ultimatum’, The New York Times, 26 February 2020 (https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/26/world/asia/delhi-riots-kapil- mishra.html); OHCHR, Communications report of special procedure India JAL IND 15/2020, 9 October 2020: (https://spcommreports.ohchr.org/ TMResultsBase/DownLoadPublicCommunicationFile?gId=25603).

21. ‘HC Judge who pulled up Delhi police over riots shunted out by Modi govt’, The Wire, 27 February 2020 (https://thewire.in/law/modi- government-wastes-no-time-moving-justice-muralidhar-out-of- delhi-high-court).

22. Chander, M., ‘An arbitrary crackdown on foreign donations cripples NGOs at a time when India needs them most’, Article14, 27 January 2022 (https://article-14.com/post/an-arbitrary-crackdown-on-foreign- donations-cripples-ngos-at-a-time-when-india-needs-them-most- 61f20bac480a9).

23. For a criticism of the assessments of Indian democracy by the EIU, V-DEM, and Freedom House, see: Babones, S., ‘Indian democracy at75: Who are the barbarians at the gate?’, The Quadrant, 5 August 2022 (https://quadrant.org.au/opinion/qed/2022/08/indian-democracy-at-75- who-are-the-barbarians-at-the-gate/).

24. Alizada, N. et al., Autocratization Turns Viral – Democracy Report 2021, V-Dem Institute, University of Gothenburg, 2021; Boese, V. et al.,Autocratization Changing Nature? Democracy Report 2022, V-Dem Institute, University of Gothenburg, 2022.

25. Freedom House, Freedom in the World 2022 (https://freedomhouse.org/ country/india/freedom-world/2022).

26. Roy, S., ‘Jaishankar on global democracy downgrade: “Custodians can’t stomach we don’t want their approval’” The Indian Express, 15 March 2021 (https://indianexpress.com/article/india/global-democarcy-downgrade- custodians-cant-stomach-we-dont-want-their-approval-7228422/).

27. Shantha, S., ‘Official panel sees “Western bias” in India’s poor ranking on World Press Freedom Index’, The Wire, 14 March 2021 (https://thewire. in/media/official-panel-western-bias-india-poor-ranking-world-press-freedom-index).

28. Dutta, A., ‘EIU declined India’s offer to use govt data for Democracy Index’, Hindustan Times, 31 August 2021 (https://www.hindustantimes. com/india-news/eiu-declined-india-s-offer-to-use-govt-data-for- democracy-index-101630368712964.html).

29. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), ‘Bachelet dismayed at restrictions on human rights, NGOs and arrests of activists in India’, Press releases, 20 October 2020 (https://www.ohchr.org/en/ press-releases/2020/10/bachelet-dismayed-restrictions-human-rights- ngos-and-arrests-activists-india?LangID=E&NewsID=26398). See also the paragraphs on India in the following statements: OHCHR, ‘Bachelet updates Human Rights Council on recent human rights issues in more than 50 countries’, Statements, 26 February 2021 (https://www.ohchr. org/en/2021/02/bachelet-updates-human-rights-council-recent- human-rights-issues-more-50-countries?LangID=E&NewsID=26806); OHCHR, ‘Environmental crisis: High Commissioner calls for leadership by Human Rights Council member states’, Statements, 13 September 2021 (https://www.ohchr.org/en/2021/09/environmental-crisis-high- commissioner-calls-leadership-human-rights-council-member- states); OHCHR, ‘Global Update: Bachelet urges inclusion to combat “sharply escalating misery and fear”’, Speeches, 7 March 2022 (https:// www.ohchr.org/en/speeches/2022/03/global-update-bachelet-urges- inclusion-combat-sharply-escalating-misery-and-fear).

30. The Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif tweeted on the Delhi violence, saying, ‘Iran condemns the wave of organized violence against Indian Muslims. (…) We urge Indian authorities to ensure the well-being of ALL Indians & not let senseless thuggery prevail (…)’. In response, the Indian MEA summoned the Iranian Ambassador in Delhi and lodged‘a strong protest (…) against the unwarranted remarks made by the Iranian Foreign Minister’, 2 March 2020 (https://twitter.com/jzarif/ status/1234519783435067392).

31. ‘Delhi Riots: OIC statement highlighting violence against Muslims “misleading”, says MEA’, The Wire, 27 February 2020 (https://thewire.in/ communalism/oic-delhi-muslims-mea).

32. OIC, ‘OIC expresses deep concerns over continued attacks on Muslims in India’, 14 March 2022 (https://www.oic-oci.org/topic/?t_id=30849&t_ ref=19650&lan=en)

33. ‘“Communal mindset”: India skewers OIC over statement on Muslims in India’, The Hindustan Times, 15 February 2022 (https://www. hindustantimes.com/india-news/communal-mindset-india-skewers- oic-over-statement-on-muslims-in-india-101644940905895.html).

34. Bhattacherjee, K., ‘Stop irresponsible comments on Delhi violence, India tells U.S. critics’, The Hindu, 27 February 2020 (https://www.thehindu. com/news/national/stop-irresponsible-comments-on-delhi-violence- india-tells-us-critics/article30929884.ece).

35. ‘No scope for outside interference in India’s internal matters: Venkaiah Naidu’, The Hindu, 27 January 2020 (https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/ india/no-scope-for-outside-interference-in-indias-internal-matters- venkaiah-naidu/articleshow/73670386.cms).

36. ‘India on way to become ‘Vishwa Guru’ under PM Narendra Modi: Amit Shah’, The Indian Express, 19 August 2017 (https://indianexpress.com/ article/india/india-on-way-to-become-vishwa-guru-under-modi- amit-shah-4804375/).

37. Ahmed, A., ‘India says it is importing Russian oil to manage inflation’, Reuters, 8 September 2022 (https://www.reuters.com/business/ energy/india-finmin-says-importing-russian-oil-part-inflation- management-2022-09-08/).

38. With the general election of 2024 and the centenary anniversary of the RSS foundation (in 2025) looming on the horizon, the Hindu nationalist movement is not likely to ease up on its campaign against minorities and dissenting voices.