You are here

China's footprint in Latin America

Introduction

Latin America’s external relations have historically been shaped mainly by the region’s relationship with the United States and Europe. In contemporary times, China has been interested in the region since the Cold War period. Until the late 1990s, relations between Asia and Latin American and the Caribbean (LAC) were relatively limited, with the notable exception of Japan, which has established strong diplomatic, trade, economic and development ties with several countries in the region, particularly Brazil, Mexico and Peru. More recently, other Asian countries such as India and South Korea and some countries belonging to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) such as Vietnam have begun to develop closer relations with LAC. It is especially in the last two decades that Asian countries, and first and foremost China, have begun to play a more important role in the foreign relations of Latin American countries.

China’s political engagement with Latin America from the early 2000s until today has been based on its strategy of so-called ‘South-South’ or ‘mutually beneficial’ cooperation (1). The Third World narrative of ‘respect for sovereignty’ and ‘non-interference’ globally advocated by Beijing in its diplomacy converged with the economic and political interests of leaders of the ‘New Latin American Left’ (such as Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, Lula da Silva in Brazil, Evo Morales in Bolivia or Rafael Correa in Ecuador). Although these leaders were wary of jeopardising their privileged trade relations with the United States, they were drawn to the idea of a bilateral rapprochement with Beijing that could reduce their dependence on the American market (2).

This Brief will examine China’s footprint and influence in Latin America and the Caribbean in order to highlight recent developments and challenges ahead. The first section shows how China has taken full advantage of the lucrative trade and investment opportunities offered by Latin America to establish itself as a key economic player in the region. It also shows that the growing economic interdependence between China and a large number of LAC countries is asymmetric. In some cases, the development of economic, financial and technological ties greatly increases Beijing’s capacity to exert leverage over its partners. The second section shows how the growing economic dependence of LAC countries on China and the projection of its governance ‘model’ allow Beijing to gradually extend its political influence in the region by differentiating itself from other powers. The concluding section contrasts Beijing’s mode of engagement in LAC with that of other external players, and analyses to what extent China’s growing presence poses a challenge to the EU.

A trajectory of growing economic dependence on china

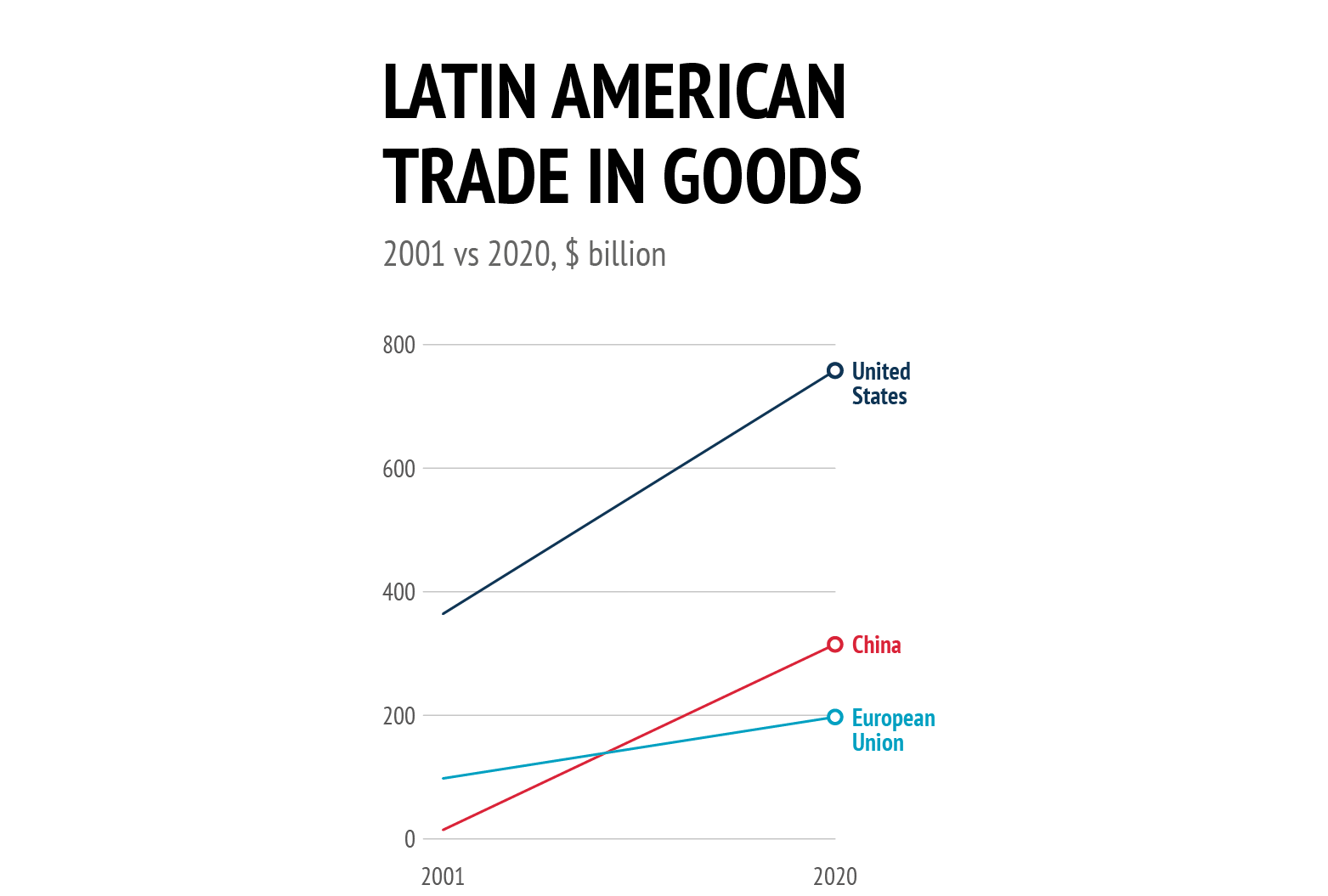

Over the past two decades, China has emerged as a key trading partner for Latin America. Compared to the United States and the EU, Latin America’s bilateral trade in goods with China grew dramatically in this period, from $14.6 billion in 2001 to $315 billion in 2020, a 21.5-fold increase since Beijing joined the World Trade Organization (WTO). During the same period (2001-2020), trade in goods between the United States and Latin America increased from $364.3 billion to $758.2 billion (a twofold increase) and trade in goods between the EU countries and Latin America increased from $98 billion to $197.4 billion (also a twofold increase).

This increase has allowed China to become the most important export market for South America and the second-largest trading partner (in goods) for Latin America as a whole, after the United States, far ahead of the EU. In 2020, given the sharp economic downturn in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, Latin America’s trade with China even reached record levels as a percentage of regional GDP, with imports estimated at 3.8 % of GDP and exports at 3.2 % of GDP(3). This growth looks likely to continue. If China’s trade with Latin America follows its current trajectory, it could double to $700 billion by 2035. China’s share of the region’s total trade could thus rise from less than 2 % in 2000 to 25 % in 2035, with significant variations between countries. On a regional scale, according to some scenarios, China could catch up with and even overtake the United States as Latin America’s largest trading partner (4).

Data: IMF, 2022

Despite this increase, trade between China and Latin America remains highly concentrated, both geographically and in terms of goods. A small number of commodities continue to dominate LAC countries’ exports to China. Between 2015 2019, almost 70 % of Latin American exports were composed of five commodities: soybeans and other oilseeds, crude oil, copper ores and concentrates, iron ores and concentrates, and refined copper. Overall, about 90 % of the flows for these main commodities came from four countries: Brazil, Chile, Peru and Venezuela (5). In the other direction, Beijing exports mainly manufactured goods, which are increasingly technology-intensive. The growing presence of Chinese companies in the information and communications technology (ICT) sector in LAC coupled with Beijing’s increasing emphasis since 2016 on the ‘Digital Silk Road’ in this region is a huge driver of these exports. Despite Beijing’s rhetoric about complementarity between trading partners, the structure of trade between China and Latin America is characterised by asymmetry, mirroring the pattern of China’s relations with countries with which it has forged economic ties in other parts of the world.

The intensification of trade with China could therefore increase the economic dependence of LAC countries in the years to come, raising fears of a repeat of the type of ‘centre-periphery’ dynamic that has characterised Latin America’s relationship with external powers in the past. In the early 2000s, increased trade with Beijing brought economic and social benefits to some of them, including in the form of poverty reduction. For instance, Brazil’s economy grew by 3.3 % and poverty levels decreased from 13.6 % in 2001 to 4.9 % in 2013 (6). After 2012, however, China’s economic slowdown and fluctuating commodity prices on the international market have had serious socio-economic repercussions for Latin America. At the same time, the increase in Chinese manufactured exports has also contributed to the process of deindustrialisation – known as reprimarisation – already underway since the 1980s and 1990s in Latin American economies, notably in Argentina and Brazil (7).

This phenomenon has economic, social, environmental and health consequences for the countries in the region. Latin America is characterised by strong socio-economic inequalities that the Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated (8). Furthermore, the increase in exports of agricultural and marine products in recent years has amplified certain existing environmental problems, such as deforestation, and has created additional ones (various forms of pollution, illegal fishing, etc).

Alternative but conditional funding

China is also expanding its financial footprint in Latin America. Since 2005, China’s two main policy banks – China Development Bank and China-Export Import Bank – have provided more than $141 billion in loan commitments to LAC countries and state-owned enterprises, more than the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) or the Latin American Development Bank (CAF) (9). They mainly concern four countries (Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador and Venezuela), which account for almost 93 % of the total (10). Most of these loans were spent on energy (69 %) and infrastructure (19 %) projects (11). In total, Latin America was the recipient of 24 % of the loans granted by Chinese official institutions worldwide between 2005 and the end of 2021, ranking in terms of geographical destination behind Asia (29 %) but ahead of Africa (23 %) (12).

Unlike the international financial institutions, Beijing does not attach governance and project feasibility standards to its loans.

Chinese sovereign loans differ from bilateral loans granted by more traditional international lenders in terms of their availability and size (13). For states such as Argentina, Ecuador or Venezuela, they have been an alternative when access to financing from international financial institutions (IFIs) has been made impossible for various reasons (corruption, weak economic fundamentals, project feasibility problems, over-indebtedness, etc). Unlike the IFIs, Beijing does not attach governance and project feasibility standards to its loans. China thus acts as a lender of last resort for countries that have lost the confidence of traditional international lenders.

However, Chinese contracts contain special confidentiality clauses and ensure repayment priority over other creditors. According to a recent study of 100 Chinese loan contracts (14), many loans have inbuilt collateral mechanisms, such as Chinese-controlled revenue accounts. In this scheme, profits from the sale of commodities by a debtor are deposited in an account controlled by Beijing. They serve as collateral for the loan. This is the case for example of the $1 billion oil-backed loan granted in 2010 by the China Development Bank to Ecuador. More problematically, this loan contract also contains policy change clauses that allow China to cancel a loan if the debtor country undertakes policy changes ‘unfavourable to “any PRC entity” in the borrowing country’. These clauses constrain Ecuador’s ability to adopt domestic policies that could negatively impact Chinese interests. They put pressure on the country to maintain positive bilateral relations with China, as a default on the loan could trigger a series of punitive measures, such as cross-defaults on other Chinese loans to the country or mandatory prepayment of the defaulting loan. In addition, several of the China Development Bank’s contracts with Argentina also include so-called ‘No Paris Club’ clauses that exclude Chinese debt from the Paris Club’s collective restructuring efforts, thereby ensuring that Beijing is prioritised over other bilateral creditors and allowing it to benefit from multilateral debt relief efforts (15).

As a result, China’s bilateral loans to Latin American countries create significant leverage for Beijing. Even in the absence of asset seizures to offset debt, sustained debt pressure shapes these countries’ long-term policies towards Beijing. In Ecuador and Venezuela, this leverage manifests itself in China’s sustained access to discounted oil for in-kind repayments through resource-backed loans. Although Chinese resource-backed loans have at times provided below-market rate financing, falling world oil prices have forced both countries to dedicate greater volumes of oil production to repaying Chinese loans (16). Faced with its own growing public debt, Ecuador even had to negotiate an International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailout of $4.2 billion in 2019 and another IMF loan of $6.5 billion in 2020 (17). In August 2020, the Venezuelan government negotiated an agreement with Chinese banks to extend payment on some $19 billion in loans, which are to be repaid by oil shipments (18). China and Venezuela have not confirmed since then whether the grace repayment period is still in effect (19). Some voices in the region have denounced these Chinese loans as ‘debt trap diplomacy’ (20).

China’s role as a provider of foreign direct investment

China’s presence in the specific area of FDI is often overstated by observers. In Latin America, between 2000 and 2020 Chinese companies invested around $160 billion in about 480 transactions, mainly through mergers and acquisitions and, to a lesser extent, greenfield projects, and other non-financial direct investments. However, these transactions represent only 5.74 % of the total FDI received by the region for the period 2000-2020. Beijing’s weight in Latin America’s FDI remains small compared to that of the EU and the United States, which together account for around 70-80 % of the FDI received by the region between 2010 and 2020 (21).

That said, Chinese FDI has nonetheless grown significantly since the mid-2000s. In terms of geographical destination, the main recipient countries have changed over time: Brazil and Argentina for the period 2010-2014, then Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru since 2017. In terms of sectors, between 2000 and 2020 Chinese FDI was concentrated mainly in energy (36.7 %), metals, minerals and mining (35.7 %), auto parts and automobiles (4.1 %), electronics (2.4 %), telecoms (2.4 %) and transport (2.2 %) (22). However, a gradual process of diversification began in 2010. Chinese companies have become more interested in electricity, the construction of transport infrastructure (especially ports such as the Paranaguá Container Terminal in Brazil, one of the largest container terminals in South America, acquired in 2018 by China Merchants Port Holdings (23)) and, to a lesser extent, in manufacturing, the financial sector, but also ICT (24).

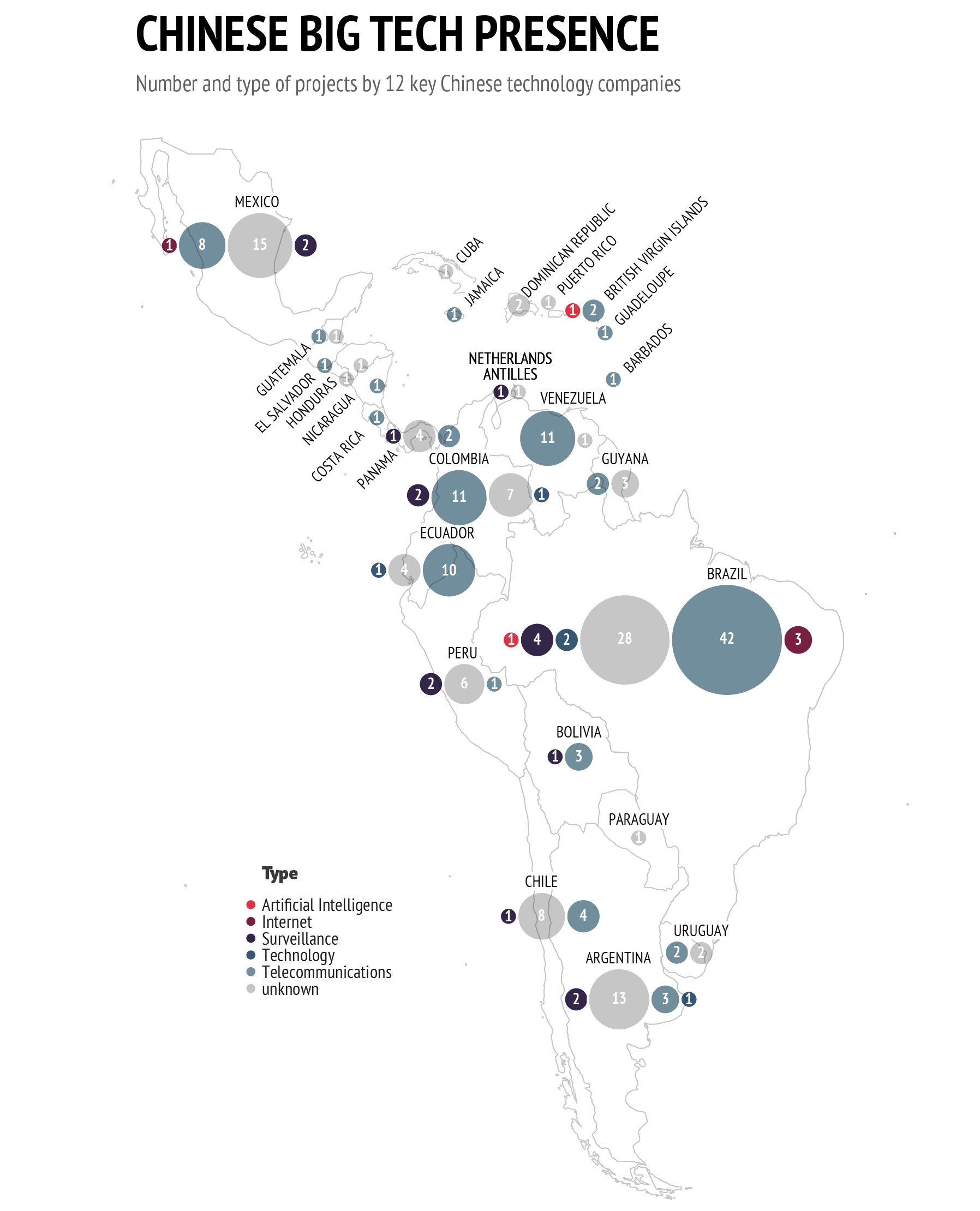

According to figures from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s International Cyber Policy Centre, 12 of China’s largest technology companies – including Huawei, China Telecom and ZTE – have undertaken new operations in 15 Latin American countries since 2015, with investments in data centres, telecoms networks and secure city projects (25). Although they accounted for only 6 % of the total amount of FDI announced during this period, the growing presence of Chinese companies in the ICT sector in Latin America, coupled with Beijing’s increasing emphasis since 2016 on the ‘Digital Silk Road’ in the region, has fuelled concern in Washington (26).

China's expanding political influence

China’s economic penetration has been leveraged and accompanied by greater political engagement with Latin America. A roadmap (China’s Policy Paper on Latin America and the Caribbean) published in 2008 (27) and updated in 2016 (28) has defined China’s Latin American policy priorities. Beijing relies on strengthening political dialogue to promote its interests at the regional level and on deploying extensive public diplomacy to reassure its partners at the bilateral level.

On the multilateral front, China has pursued a long-term strategy through increased participation in regional organisations. It has sought to engage in political dialogues, such as with the Rio Group in 1990, Mercosur in 1997, the Andean Community (CAN) in 2000 and the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) in 2005. It has also sought to be associated with regional political institutions, such as the Latin American Parliament, the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) and the Organization of American States (OAS), in which it has held permanent observer status since 2004. China is also positioned in other multilateral institutions to which it provides financial and/or political support, or which it has sometimes helped to set up. It has also participated in the establishment of new multilateral forums, such as the East Asia-Latin America Cooperation Forum (EALAC), of which it has been a member since its creation in 1999, the China-Caribbean Economic and Trade Cooperation Forum (CCETCF), initiated in 2005, and above all the Cooperation Forum between China and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC). Beijing adopted a ‘comprehensive cooperation partnership’ with CELAC members in 2014. This partnership launched the triennial China-CELAC summits aimed at defining (2015) and then updating (2018 and 2021) roadmaps for cooperation in various fields (political, economic, security, etc.), which indicate Chinese priorities in the region. The Forum also provides an opportunity to reach out to countries with which China has no diplomatic ties, such as some Central American states that would later break with Taiwan in favour of Beijing (Panama, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Nicaragua).

Data: ASPI, Mapping China's tech giants, 2022; European Commission, GISCO, 2022

Political dialogue has also been promoted within the framework of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which was extended to Latin America in 2017. At the first Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in Beijing in May 2017, attended by the presidents of Argentina and Chile, Xi Jinping described Latin America as a ‘natural extension of the Maritime Silk Road’. At the China-CELAC summit in January 2018, Beijing officially invited the 33 CELAC member countries to join its initiative in an agreement to deepen economic and political cooperation. Some 20 LAC countries have since signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with China under the BRI.

On the bilateral level, the strengthening of political ties has been observed through an increase in high-level diplomatic visits, particularly since Xi Jinping took office in 2013. The Chinese president has visited LAC four times, compared to only one visit by former US president Donald Trump. China has pushed to relabel its bilateral relations with Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, Venezuela and Uruguay ‘strategic partnerships’ of various types (29). China has also managed to strengthen its diplomatic presence in the region, establishing official relations with countries that previously recognised Taiwan, thus reducing Taipei’s diplomatic space. China managed to convince these countries through high-level but discreet diplomatic activism and with promises of short-term investment in strategic sectors to boost their economic development (30).

The links between Latin America and East Asia look set to grow stronger in the coming decades as the global economy shifts from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

China has also sought to conclude free trade agreements (FTAs) with its Latin American partners that have adopted and maintained a policy of trade and financial liberalisation along the lines of the neo-liberal Washington consensus: Chile (2005), Peru (2009) and Costa Rica (2010). These three countries have formally committed to recognising China’s market economy status and in exchange they benefit from more advantageous tariff conditions in terms of access to the Chinese market than those granted by the general most favoured nation regime. Beijing has also expressed interest in negotiating free trade agreements with Ecuador and Uruguay. Negotiations are also underway with Colombia and Panama. These states, which all have free trade agreements with the EU and the United States, are part of various regional groupings such as the Pacific Alliance (Chile, Peru and Colombia), the Andean Community (Peru, Ecuador and Colombia), Mercosur (Uruguay) and the Central American Integration System (Costa Rica and Panama).

The growing importance of China, and more broadly East Asia, as a destination for Latin American exports since the 2000s has led to a reorientation of the diplomacy of many LAC countries towards the Pacific. This has been seen with the creation in 2018 of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP or TPP11). The links between Latin America and East Asia look set to grow stronger in the coming decades as the global economy shifts from the Atlantic to the Pacific, a trend which is expected to continue into the 21st century.

Beijing’s charm offensive

China has no military capabilities in the region, despite regular high-level exchanges with military officials (notably in the framework of the ‘China-Latin America High-level Defense Forum’ launched in 2012) and arms sales to several LAC countries (notably Venezuela) (31). Its interventions in Latin America have so far been much more discreet than those of the United States. China has adopted a strategy of engaging in significant public diplomacy in Latin America, proclaiming its solidarity and community of interest with developing countries vis-à-vis the more developed countries, and placing their relations under the aegis of ‘South-South’ cooperation (implying an ‘egalitarian’ relationship between ‘partners’ as opposed to hierarchical relations with the countries of the ‘North’), and invoking the five principles of peaceful coexistence (32) enunciated by Zhou Enlai in the 1950s. Beijing promotes a vision of the international order dubbed the ‘coexistence model’ (33), which is based on the principles of sovereignty and non-interference in internal affairs, with the corollary of ‘neutrality’ with regard to the political systems of other states. Through this model of governance, China is also putting forward a new vision and interpretation of democracy. In a White Paper entitled ‘China: Democracy that works’ published in December 2021, Beijing refers to a new ‘model of democracy’ of which China’s policy would be the best expression and which could serve as an example to other countries (34). All these principles are interpreted in a strict and conservative manner compared to the more fluctuating Western interpretations, and they are echoed by authoritarian states in the region because of the numerous external interferences that Latin America has experienced in the past.

Beyond this narrative, China has multiplied the soft power tools used to extend its influence in the region. The growing number of Confucius Institutes and classes established in LAC countries is the most visible manifestation of this. Currently, there are 45 Confucius Institutes in some 23 countries in the region (35). These institutes are an important lever of influence in the Caribbean countries, especially since the Beyond this narrative, China has multiplied the soft power tools used to extend its influence in the region. The growing number of Confucius Institutes and classes established in LAC countries is the most visible manifestation of this. Currently, there are 45 Confucius Institutes in some 23 countries in the region (35). These institutes are an important lever of influence in the Caribbean countries, especially since the United States does not have an official diplomatic presence there. While China has an embassy in every Caribbean country with which it has diplomatic relations, the United States has an embassy in Barbados that serves as a diplomatic representation for the six other Caribbean countries. Beijing is also developing cultural (36) and educational cooperation, by providing scholarships, ‘training places’ and ‘talent programmes’ for Latin Americans to study or learn job skills in China. The China-CELAC Academic Forum is also an opportunity for Latin American academics to travel to China on an extended trip usually funded by the Chinese government. Beijing is also trying to project its influence through the dissemination of Chinese media aimed at a Spanish-speaking audience (37) and through more informal channels via a relatively old diaspora settled in the region. After Asia, the Americas are home to the largest number of overseas Chinese (38).

As elsewhere in the world, through the multiple channels and organisations that make up its ‘United Front System’, Beijing seeks to increase and amplify its influence in the region. It is developing networks among local elites by inviting political party leaders, officials, or parliamentarians from LAC countries to China. Between 2002 and 2017, representatives of the Chinese Communist Party’s International Liaison Department held nearly 300 meetings with 74 different political parties in 26 of the 33 LAC countries (39). China also promotes the establishment of parliamentary groups or friendship associations. For example, in Panama, there is an Association of Friendship with China (Asociación Panameña de Amistad con China -APACHI) with over 350 members, including prominent public figures, businessmen, intellectuals and academics.

The US administration’s lack of interest in Latin America is reflected in its modest pledge in 2021 to spend $4 billion on development projects.

This public diplomacy is bearing fruit in a number of countries where Beijing scores more favourably than Washington, such as Argentina, Chile, Mexico, Peru and Venezuela. A survey conducted in April 2019 by the Chilean polling company CADEM showed that 77 % of Chileans have a positive image of China compared to 61 % for the United States (40). The same is true in Mexico, according to a 2018 Latinobarómetro poll, with 57 % of respondents compared to 43 % for the United States. In Argentina, 51 % perceive China positively compared to 45 % for the United States. In Peru, Beijing also won the public opinion race with 59 % against 56 % for Washington. In Venezuela, China is also in the lead (63 % vs. 62 %) according to the same survey (41). And this support could continue to grow. In the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, China was also active in LAC through its ‘vaccine diplomacy’ and its various supplies of medical equipment and facilities (42). It should be noted, however, that Washington’s donations to countries in the region were much larger than China’s often very limited ones, which did not prevent Beijing from going to great lengths to publicise its aid to various countries. The Chinese media skilfully staged its deliveries, without it being clear whether they were ‘donations’ or sales.

Latin America as an arena of strategic competition

Both the United States and the EU now see China as a strategic global competitor. The Biden administration has asserted that the United States will confront China whenever its behaviour threatens US interests and values (43). The EU, meanwhile, has a more nuanced position towards China, simultaneously portrayed as a ‘negotiating partner’ in some areas and an ‘economic competitor’ in others. It has also labelled Beijing as a ‘systemic rival in promoting alternative governance models’ (2019) and launched the Global Gateway Initiative (2021) that could be considered as an alternative to Beijing’s ‘New Silk Roads’, particularly in the digital field in Latin America (44). In June 2021, G7 leaders agreed to launch a global infrastructure initiative, ‘Build Back Better World’ (B3W), to advance infrastructure development in low- and middle-income countries. Latin America will be part of this initiative, which was renamed the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) and launched in June 2022 (45).

China’s rise in Latin America has raised concerns in Washington, but it has not yet fundamentally changed US foreign policy towards the region. The Biden administration has adopted a more conciliatory diplomatic rhetoric towards LAC countries than its predecessor at the beginning of its term. By announcing the launch of a new economic proposal called the ‘Economic Prosperity Partnership of the Americas’ (APEP) to deepen economic ties in the hemisphere, Biden used the ninth Summit of the Americas in June 2022 to reassert US leadership in Latin America after years of neglect. However, its priorities are above all the management of the Covid-19 pandemic, the recovery of the US economy, the relationship with Russia (severely strained by the war in Ukraine), the pursuit of policies to contain Chinese expansion on a global scale and the rapprochement with its traditional Asian and European allies, with Latin America being relegated to second place. The US administration’s lack of interest in the region is reflected in President Biden’s modest pledge in 2021 to spend $4 billion on development projects in Latin America (46). This sum is almost insignificant when compared to the nearly $4 000 billion announced for the US economic stimulus and infrastructure modernisation plans (47) or to the amounts that China is promising in the region through the BRI in particular – estimates for the BRI as a whole have ranged from $1 000 to $8 000 billion. Unlike the United States, China has limited military projection capabilities at the global level and projects an image of sharp power in Latin America.

Conclusion

For a long time, Latin America was the backyard of the United States, but Europe also shares important historical, cultural and commercial ties with this region, with which it established a ‘bi-regional strategic partnership’ in 1999, strengthened in 2005, renewed in 2009 and deepened in 2015. Between the 1980s and the 2000s, Europe’s model of regional integration was seen as the best alternative to reduce the dependence of South American states on the US market. From the early 2000s onwards, however, several factors contributed to the EU’s loss of attractiveness in the region. Today, Latin America is also a playground for China (48).

According to a 2022 survey, Latin Americans’ perceptions of the United States, the EU and China seem to vary according to the type of leadership these three actors project in the region: military-strategic leadership (primacy of the United States), economic-technological leadership (preponderance of China), and normative and values-based leadership (pre-eminence of the European Union) (49). The United States and the EU remain, overall, privileged partners for Latin America, but China is also projecting its model of economic development in the region, including its distinctive model of governance, with varying degrees of success. Unlike the EU, China does not present itself as a normative power seeking to influence the political agendas and economic and trade regulations of LAC countries. It projects the image of a pragmatic power capable of responding to the immediate needs of Latin American states and elites.

By promoting its model of governance and economic development, China competes with the norms, standards and good practices advocated by the EU – including in terms of democratic governance, respect for the rule of law, transparency, inclusiveness, free competition, corporate responsibility (due diligence), respect for the environment, etc. This is not to mention the direct and indirect support that Beijing provides to authoritarian regimes in Latin America. This support contributes to an erosion of democracy and human rights in these states, but also more generally in a region where a growing number of citizens seem to be increasingly indifferent to the political regime that governs their country. These issues pose significant challenges for the EU.

References

1. China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ‘China’s stand on South-South cooperation’, Beijing, 18 August 2003 (https://www.mfa.gov.cn/ce/ceun// eng/gyzg/wjzc/t24884.htm).

2. Wintgens, S., ‘Chine-Amérique latine et Caraïbes : un défi normatif pour l’Union européenne?’, Politique européenne, No. 60, 2018, pp. 142-143.

3. Ray, R., Albright, Z.C. and Wand, K., ‘China-Latin America Economic Bulletin – 2021 Edition’, Global Development Policy Center, 22 February 2021, p. 1.

4. Zhang, P. and Prazeres, T., ‘China’s trade with Latin America is bound to keep growing. Here’s why that matters’, World Economic Forum, 17 June 2021; Prazeres, T., Bohl, D. and Zhang, P., China LAC Trade: Four scenarios in 2035, Atlantic Council, Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center, Washington, April 2021, p. 12.

5. ‘China-Latin America Economic Bulletin – 2021 Edition’, op. cit., p. 9.

6. Moreno, L.A., ‘Latin America’s Lost Decades: The toll of inequality in the age of Covid-19’, Foreign Affairs, January/February 2021.

7. Cooney, P., ‘Reprimarization: Implications for the environment and development in Latin America – The cases of Argentina and Brazil’, Review of Radical Political Economics, Vol. 48, No 4, 2016, pp. 553-561.

8. Carreras, M., Vera, S. and Visconti, G., ‘A tale of two pandemics: Economic inequality and support for containment measures in Peru’, Journal of Politics in Latin America, Vol. 13, No 3, 2021, pp. 358-375.

9. Myers, M. and Ray, R., ‘China in Latin America: Major impacts and avenues for constructive engagement – A U.S. Perspective’, China Research Center, China Currents, Vol. 19, No 1, 2020.

10. Details by country in Gallagher, K. and Myers, M., ‘China-Latin America finance database’, Inter-American Dialogue, Washington, 2021 (https:// www.thedialogue.org/map_list/).

11. Quoted in ‘China’s Engagement with Latin America and the Caribbean’, Congressional Research Service, In Focus, 4 May 2022 (https://sgp.fas.org/ crs/row/IF10982.pdf).

12. Quoted in Louis, B. and Sary, Z., ‘Le positionnement de la Chine parmi les bailleurs en Afrique subsaharienne’, Ministère de l’Économie, des Finances et de la Relance, Trésor-Eco, No 292, November 2021, p. 2.

13. However, these advantages often overshadow higher interest rates than those proposed by IFIs (although they may be lower than commercial rates), shorter terms and reduced payment deferrals. According to AidData, a typical loan from China has an interest rate of 4.2 % and a repayment period of less than 10 years. By comparison, a typical loan from an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) lender, such as Germany, France or Japan, has an interest rate of 1.1 % and a repayment period of 28 years. AidData, ‘AidData’s new dataset of 13,427 Chinese development projects worth $843 billion reveals major increase in “hidden debt” and Belt and Road Initiative implementation problems’, 29 September 2021.

14. Gelpern, A. et al, ‘How China lends: A rare look into 100 debt contracts with foreign governments’, Center for Global Development, AidData at William & Mary, Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Peterson Institute for International Economics, 31 March 2021.

15. Ibid, pp. 6-7, p. 28 and pp. 34-39.

16. Mihalyi, D., Adam, A. and Hwang, J., ‘Resource-backed loans: pitfalls and potential’, Natural Resource Governance Institute, February 2020.

17. IMF, ‘IMF Executive Board approves US$4.2 billion extended fund facility for Ecuador’, 11 March 2019; IMF, ‘IMF Executive Board approves 27-month US$6.5 billion extended fund facility for Ecuador’, 30 September 2020.

18. Armas, M. and Pons, C., ‘Exclusive: Venezuela wins grace period on China oil-for-loan deals, sources say’, Reuters, 12 August 2020.

19. mAizhu, C. and Parraga, M., ‘Exclusive – Chinese defence firm has taken over lifting Venezuelan oil for debt offset – sources’, Reuters, 26 August 2022 (https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/chinese- defense-firm-has-taken-over-lifting-venezuelan-oil-debt-offset- sources-2022-08-26/).

20. This is the case of some scientists such as Alfredo Michelena, a Venezuelan sociologist from the Universidad Católica Andrés Bello. Michelena, A., ‘Venezuela y la tóxica deuda china’, Analitica, 24 February 2021.

21. Dussel-Peters, E., ‘Monitor of Chinese OFDI in Latin America and the Caribbean 2021’, Red ALC-China, 31 March 2021, pp. 5-6 and p. 34 (https://www.redalc-china.org/monitor/images/pdfs/menuprincipal/ DusselPeters_MonitorOFDI_2021_Eng.pdf)

22. Ibid, pp. 7-8.

23. Kwok, D. and Parra-Bernal, G., ‘China Merchants buys control of Brazil’s most profitable port’, Reuters, 4 September 2017.

24. ECLAC, Foreign Direct Investment in Latin America and the Caribbean 2021, United Nations, Santiago, 2021, pp. 94-107.

25. Ibid, p. 113.

26. Malena, J., ‘The extension of the Digital Silk Road to Latin America: Advantages and potential risks’, Council on Foreign Relations/Brazilian Center for International Relations, 19 January 2021.

27. Xinhua, ‘Full text: China’s Policy paper on Latin America and the Caribbean’, 6 November 2008 (https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/ china/2008-11/06/content_7179488.htm).

28. PRC State Council, ‘Full text of China’s Policy Paper on Latin America and the Caribbean’, 24 November 2016 (http://english.gov.cn/archive/ white_paper/2016/11/24/content_281475499069158.htm).

29. Myers, M. and Barrios, R., ‘How China ranks Its partners in LAC’, Asia & Latin America, Inter-American Dialogue, 3 February 2021.

30. Kellner, T. and Wintgens, S. (eds.), China-Latin America and the Caribbean: Assessment and outlook, Routledge, New York & London, 2021.

31. According to the SIPRI database, between 2013 and 2020, the value of US arms exports to LAC countries was about 4 times higher than that of China. Venezuela was Beijing’s main partner for arms sales in the continent in this period. Notable transactions include the sale of 18 K-8 trainer jets in 2010, 121 VN-4 armoured vehicles in 2012, and some C-802 anti-ship missiles in 2017. (See https://armstrade.sipri.org/armstrade/ html/export_values.php).

32. The five principles of peaceful coexistence are mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual non-aggression, non- interference in each other’s internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence. Liu, N., ‘Chinese White Paper seeks to redefine Democracy’, VOA, 24 December 2021 (https://www.voanews.com/a/ chinese-white-paper-seeks-to-redefine-democracy-/6369108.html).

33. Odgaard, L., China and Coexistence: Beijing’s National Security Strategy for the Twenty-First Century, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, 2012.

34. The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, ‘China: Democracy that works’, Xinhua, 4 December 2021 (http://www. news.cn/english/2021-12/04/c_1310351231.htm).

35. See ‘Confucius Institutes around the world – 2021’, Dig Mandarin, 2021 (https://www.digmandarin.com/confucius-institutes-around-the- world.html.

36. For instance, 2016 was the ‘Year of Cultural Exchanges between China and Latin America and the Caribbean’ (See https://www.chinadaily.com. cn/culture/2016-03/15/content_23880944.htm).

37. See Barrios, R., ‘China’s state media in Latin America: profile and prospects’, Asia Research Institute Blog, The University of Nottingham, 28 May 2018.

38. Chinese communities in LAC are estimated to number over 1.8 million, with the largest communities in Peru (about 5 % of the population, or one million people). Other countries with large Chinese communities include Brazil, Panama, Argentina and Venezuela. Poston, D.L. and Wong, J.H., ‘The Chinese diaspora: The current distribution of the overseas Chinese population’, Chinese Journal of Sociology, Vol. 2, No 3, 2016.

39. Written testimony for the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, ‘Hearing on China in Latin America and the Caribbean’, 20 May 2021, p. 5 (https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/2021-05/ Ryan_Berg_Testimony.pdf).

40. CADEM Research and Estrategia, Encuesta Plaza Pública, April 2019, p. 27 (https://plazapublica.cl/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Track-PP-275- Abril-S3-VF.pdf).

41. Latinobarómetro, ‘Calificación de la relación entre el país y China/los Estados Unidos’, Analysis Online, 2018. (See https://www.latinobarometro. org/latOnline.jsp).

42. See details of donations of masks, vaccines and other medical equipment by country in the interactive database of ‘Aid from China and the U.S. to Latin America amid the Covid-19 crisis’, Wilson Center, Latin America Program, 12 January 2021.

43. The White House, ‘Interim National Security Strategic Guidance: Renewing America’s Advantages’, March 2021, p. 20 (https://www. whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/NSC-1v2.pdf).

44. European Commission, ‘EU-China - A Strategic Vision’, Joint Communication to the European Parliament, the European Council and the Council, 12 March 2019, p. 1 (https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/ files/communication-eu-china-a-strategic-outlook_fr.pdf); ‘The Global Gateway’, Joint Communication to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, the Committee of the Regions and the European Investment Bank, Brussels, 1 December 2021 (https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/joint_communication_ global_gateway.pdf).

45. ‘Our Shared Agenda for Global Action to Build Back Better’, Carbis Bay G7 Summit Communiqué, Cornwall, 13 June 2021; ‘G7 summit: Leaders detail $600bn plan to rival China’s Belt and Road initiative’, BBC News, 27 June 2022.

46. Camilleri, M.J., ‘Biden’s Latin American opportunity’, Foreign Affairs, 28 December 2020.

47. ‘Biden’s $4 trillion economic plan, in one chart’, The New York Times, 28 April 2021.

48. ‘Chine-Amérique latine et Caraïbes : un défi normatif pour l’Union européenne?’, op. cit., pp. 134-173.

49. Latinobarómetro, Nueva Sociedad & Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, ‘Latin America - European Union: views, agendas and expectations’, April 2022 (https://nuso.org/articulo/como-AL-ve-a-europa/).