You are here

India's G20 presidency

Introduction

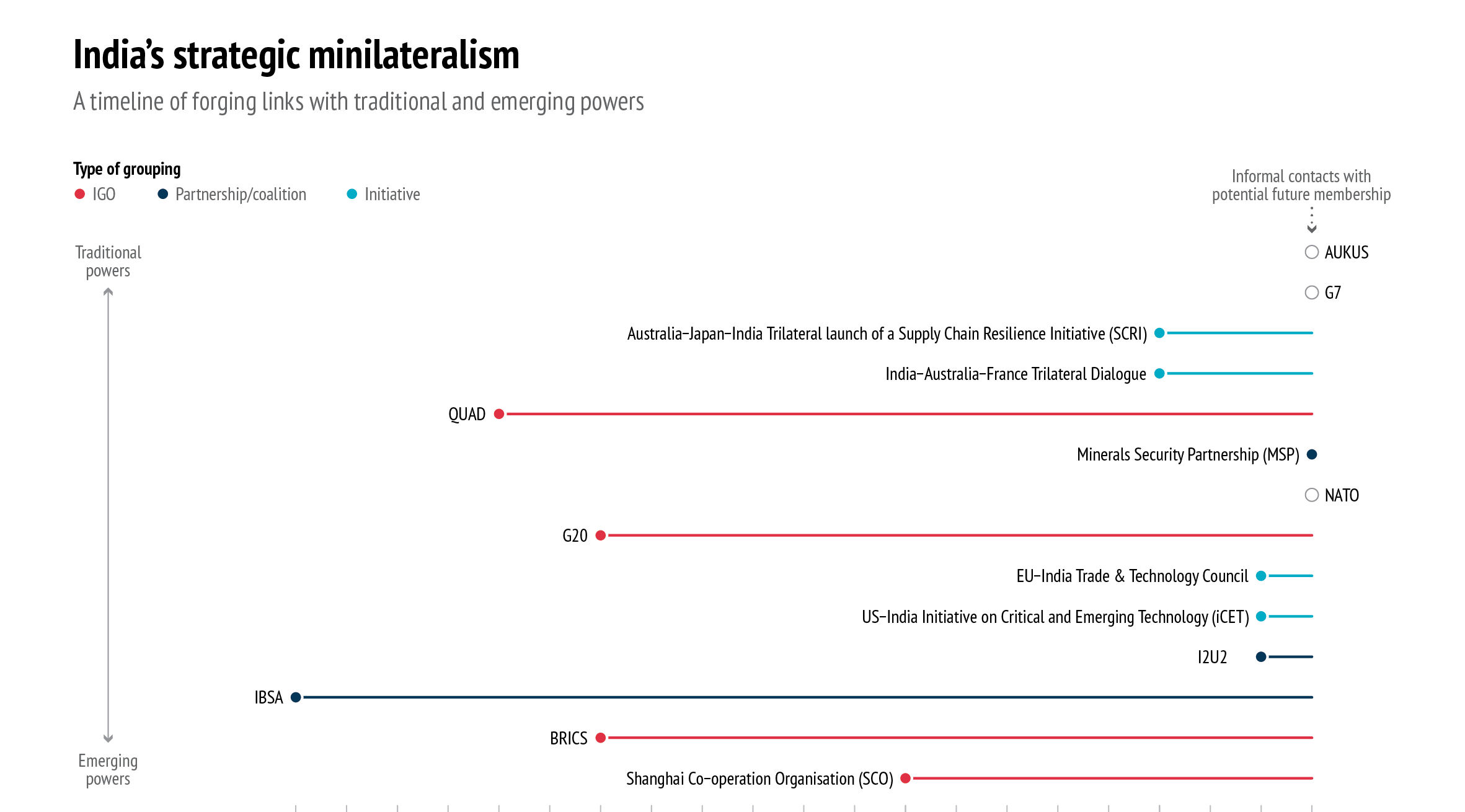

The importance of India’s assumption of the rotating presidency of the G20 was reflected in the one hundred monuments, including UNESCO World Heritage sites, that were lit up across the country for an entire week in December 2022 when the country took the helm (1). Placards bearing the portrait of Narendra Modi were displayed across New Delhi hailing the G20 as ‘a watershed moment’ where India could shoulder ‘big responsibility’ and make ‘bigger decisions’ at the ‘Global High Table’. New Delhi intends taking full advantage of the presidency to showcase its position as a multi-aligned emerging power and legitimate leader of the so-called Global South. Yet unofficial discussions with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) that took place on the margins of this year’s Raisina Dialogue and the AUKUS nations’ – (Australia, UK and US) – exploration of tech cooperation options with India earlier this year point to a broader minilateral agenda. While multilateralism is in crisis, minilateralism is on the rise (2).

This further reflects India’s own contrasting reality: some argue that it is bound to rise economically and as the most populous country in the world to become a leading power; others point to its lacklustre domestic development indicators and comparatively limited military capabilities as a major drawback to it becoming a global power. India needs to find its own place in the world as it seeks to raise its international profile. New Delhi has understood that a set of shared interests in a minilateral arrangement may allow for the co-existence of another set of divergent ones. The EU should follow suit and prioritise aligning along issue-based common interests in its minilateral relationship with India.

This Brief first seeks to understand India’s international and domestic motivations in pursuing such an active G20 presidency. It further looks at how the Indian regime is seeking to propagate its own civilisational worldviews while pursuing a transactional foreign policy. For the purpose of this analysis, it is important to look at the broader international context which includes a multilateral order in crisis, a growing preference for minilateral arrangements and the securitisation of economic interdependence. It then addresses the implications of India’s acquiescence with Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and its membership in minilateral groupings with strong Russian and/or Chinese leadership. Despite its efforts to keep Russia on side, New Delhi has been careful to build a strong relationship with its ‘like-minded’ partners, having managed to join strategic Western-led minilateral groupings, such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) and potentially the G7. The final section addresses the caveats and opportunities for EU-India minilateralism.

Understanding India's current 'minilateral agenda'.

Domestic and international motivations?

Modi’s regime regards the G20 presidency as an opportunity to highlight its achievements during the remainder of the prime minister’s tenure. The presidency has inevitably become entangled in domestic politics, against the background of nine rounds of local elections this year and a general election scheduled to take place by the end of the first quarter of 2024.

Over 200 meetings have been organised across the country on a wide range of issues, including on tourism in Jammu and Kashmir, in an attempt to project an image of normalcy following the revocation expanded to include trade, sustainable development, health, agriculture, energy, environment, climate change and anti-corruption. New Delhi has newly integrated disaster risk reduction, as well as the space economy and the Global S&T (Science and Technology) ecosystem (with a focus on the ‘One Health’ approach) as part of the G20 Sherpa Track (3).

The relationship between the current government´s domestic agenda and India´s G20 presidency soon became evident in light of the chosen logo, which juxtaposes planet Earth with the lotus, India’s national flower, as well as the emblem of the ruling Indian People’s Party (Bharatiya Janata Party - BJP). The new G20 logo evokes growth amid challenges, as well as living in harmony with the surrounding ecosystem. India´s G20 theme – ‘Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam’ or ‘One Earth, One Family, One Future’ – originates from the ancient Sanskrit text of the Maha Upanishad (4). As noted by Nirmala Sitharaman, India’s current Finance Minister, in the speech she delivered when presenting the Union Budget for 2023-24: ‘we are steering an ambitious, people-centric agenda to address global challenges, and to facilitate sustainable economic development’ (5).

Such framing aims to reflect India´s emphasis on its civilisational legacies and its wish to become a ‘norm-setter’, as opposed to just a ‘norm taker’ in a post-World War II international system. Certain analysts argue that India’s ultimate aspiration is to become a leading power – if not a great power – or, at least, a balancing power (6). India expects to achieve pole status by 2050 based on its predicted GDP (7). Aside from increasing its material capabilities – particularly in the economic and security realms – India seeks to bring its own perceptions, principles and pragmatism to the high table of international politics by adopting the role of ‘world guru’ seeking to bring about ‘global good’ (8). During the inauguration of the new Indian Parliament building in May 2023, Modi referred to the laws enacted in the new parliament house as the foundation for a ‘new India – a prosperous, strong and developed India’ (9).

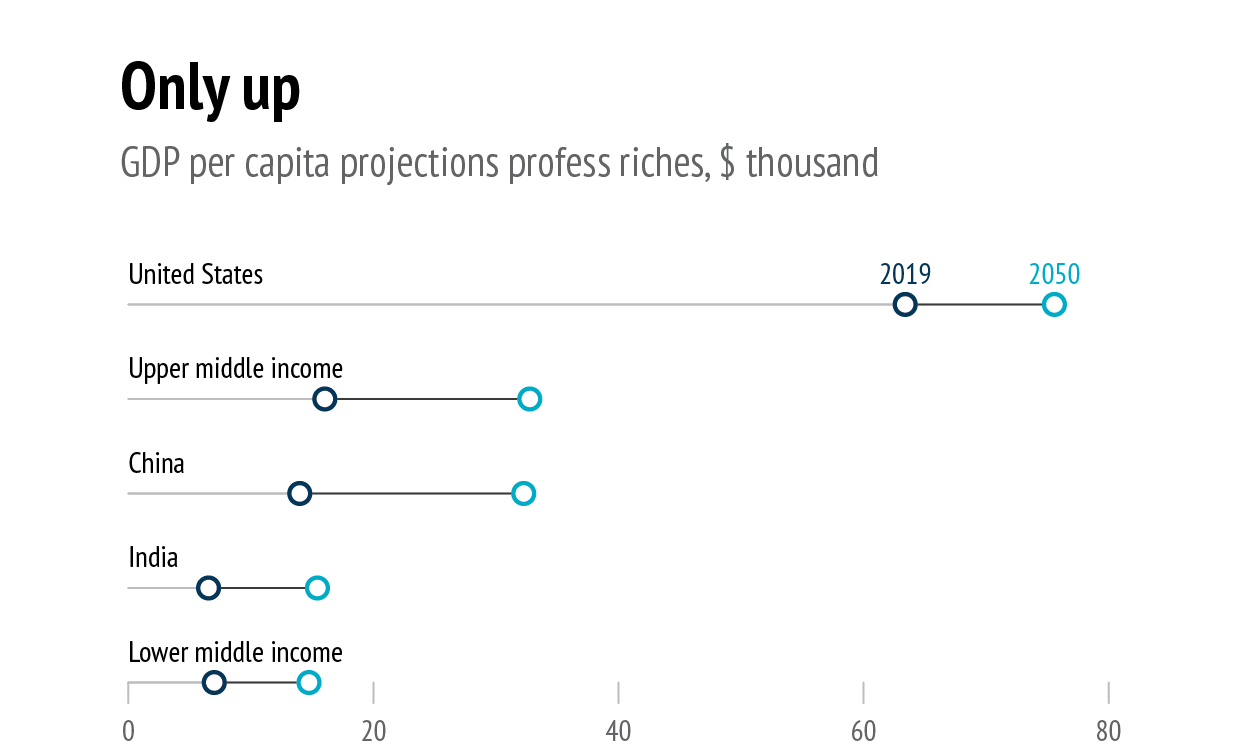

Notwithstanding India’s international aspirations, it is questionable whether it can continue to rise inexorably and have a role at the high table of international politics in view of its poor development indicators and high inequality rates (10). Poverty indicators are a controversial topic in India where the use of standardised indexes has come in for much criticism, amid allegations of Western bias. Certain analysts do not see any incoherence in India’s rural versus urban gap or in regional differences of development, and how this could adversely affect its unrealised potential. The topic is in this domain in recent years (11). Some question whether India will ever overcome its ‘disheartening periodicity’ (12) or what one analyst has labelled its ‘precocious development model’ (13). Nonetheless, India has sustained high levels of economic growth in recent years: 7 % of GDP per capita for 2022, with a predicted 5.9 % for 2023, to remain constant in the coming years (14). This could pave the way for it to become a leading power. Its predicted GDP per capita for 2050, however, lags way behind that of the United States and China (15).

Data: Center for Global Development, 2023

Modi’s regime has gone out of its way to portray an India with a unique mission in the world (16). It has further emphasised its desire to promote an international image of India as a vibrant and inclusive democracy that advocates for cooperation and moderate international competition. New Delhi stresses that it adheres to its own principles without seeking to impose its model on others, unlike ‘one particular geography’ – a euphemism for China in Delhi’s policy speak – or Western countries. Modi’s regime further links this claim to India’s ancient (Hindu) past, invoking the ‘democratic spirit integral to its civilisational ethos’ (17). India’s engagement with democracy promotion and its instrumentalisation of the liberal order is not new; its intent to present this as a counterbalance to China’s rise is, however (18).

While seeking to carve out a role as leader of the ’emerging world’, India still manages to pursue its charm offensive with the traditional powers as attested by its membership of QUAD or its cautious testing of the waters with NATO and AUKUS respectively. During the Voice of the Global South Summit organised in January 2023 New Delhi encouraged other developing countries to participate in addressing the crisis of food, fuel and fertilisers under the auspices of the G20. India has sought to make it a forum for a common agenda among developing and developed countries in key areas of convergence such as energy and food security, inflation, climate and recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic. There remain a number of contentious issues such as the reform of the Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs), clean energy transition and climate change adaptation funding together with debt relief policies for highly-indebted countries, as discussed in the recent G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors’ meeting (19). India’s sustainable development agenda continues to grow as demonstrated by its leading role in the International Solar Alliance and the Coalition for Disaster-Resilient Infrastructure.

What about the broader picture?

India’s ascension to the G20 presidency and chairmanship of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), in parallel to its invitation to this year’s G7 Summit, is illustrative of its adaptative nature. Such adaptability is useful in an increasingly fractured and divisive world order, which is conveniently portrayed in stark binary terms in today’s international policy discourse: a liberal, developed, democratic world – the ‘like-minded’ – versus an illiberal, emerging and autocratic world – the ‘non-like-minded’. India fits into neither category exactly. This division of the world into two blocs is not truly representative of reality but rather a useful normative construct that is instrumentalised to legitimise alignments based on geoeconomic and geopolitical interests. The leading powers want to belong to the democratic camp, albeit having differing conceptualisations of what this entails. The US-led Summit for Democracy or its Chinese equivalent, the International Forum on Democracy: Shared Human Values, held in parallel during 2021 and 2023, are proof of this. A similar approach is conveniently applied to different actors involved in the Russian War on Ukraine with the ‘like-minded’ supporting Ukraine against the pro-Russia ‘non-like-minded’.

New Delhi has been particularly vocal in its calls for reform of multilateral institutions

Against the backdrop of an increasingly fragmented globalised world, the United States and its allies have favoured decoupling from China, with a growing shift towards an EU-led ‘de-risking’ approach with a view to securing critical goods and building strategic interdependence. In this highly polarised environment, India’s dexterity in walking a tightrope across the ‘like-minded’ and ‘non-like-minded’ worlds, as its positioning vis-à-vis the Russian war in Ukraine has shown, suits its aspirations well. From a geo-strategic perspective, New Delhi understands that it now performs a unique counterbalancing role to an increasingly threatening China within the Indo-Pacific region. Despite the scepticism of certain onlookers, India likes to portray itself as ‘a country that is an open society and a democracy’, as noted by Rajeev Chandrasekhar, Indian Minister of State for Skill Development and Entrepreneurship and Electronics and Information Technology, following EU-India Trade and Technology Council (TTC) negotiations in Brussels during May 2023 (20).

In tangible terms, India seeks to become a leader in clean energy, food security and in the provision of digital public goods – government initiatives like India Stack and the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) are illustrative of this (21). However, India and the G7 countries do not necessarily see eye-to-eye on the need to regulate the digital economy: for New Delhi, Big Tech firms should adhere to digital rules set by state authorities, not the other way around (22). Not coincidentally, India has spearheaded an ambitious agenda to decouple technological innovation from that of Big Tech companies, with an additional emphasis on swadeshi or self-reliance in line with the principle of Atmanirbhar Bharat (23). This is demonstrated by Modi’s quest to accelerate economic development through initiatives such as ‘Make in India’, ‘Digital India’ or ‘Skill India’ in leading manufacturing and IT industries (24).

Implications of India's minilateral tightrope?

Modi’s regime is seeking to disseminate its worldviews by promulgating a narrative that invokes India’s ancient wisdom based on the principles of harmony and equality. This is done while pursuing an effective transactional approach. Some argue that Indian foreign policy is being driven more and more by immediate strategic and tactical interests rather than more abstract ‘preferences’ regarding the basic structure of the world order (25). This reflects New Delhi’s uncertainty about its place in the world. For others, India’s ‘strategic autonomy’ has been a constant variable for the country and allows it to navigate an increasingly unstable and unpredictable environment, with shifting balances of power and contending emerging poles in Asia, reflected first and foremost in the rivalry between China and India. This behaviour is not unique to New Delhi, with established powers in the region like Australia and Japan re-evaluating their defence posture and strategies (26). The United States currently also considers itself an Indo-Pacific power, as noted in the Biden administration’s Indo-Pacific Strategy unveiled in February 2022.

The key question for the future is the extent to which India can continue to tread this tightrope and stick to ‘strategic autonomy’. But what exactly does the mantra of ‘strategic autonomy’ mean? Strategic autonomy to India means that on the fundamental all those that it can work with, rather than take sides between powers. So long as India decides to engage as a partner, strategic autonomy is maintained (27). New Delhi has been adept at ‘free riding’ the current multilateral setup, making sure to advocate for a rule-based, democratic and equal world order as a responsible multilateral stakeholder and in solidarity with the developing world.

One of the most salient traits of its current multi-alignment strategy has been its capacity to adapt its ‘minilateral agenda’ vis-à-vis its issues – national security, world trade, climate change – New Delhi will cooperate and engage with ‘like-minded’ partners while skilfully acquiescing with Russia/China-led minilateral groupings, such as the SCO – at the core of the Asian heartland – or the BRICS. New Delhi has consolidated its presence in Western-led and strategic groupings in the Indo-Pacific, such as the QUAD, using its centrality in the Indian Ocean and intent to counterbalance Chinese influence in the region. The QUAD Statement from their Hiroshima meeting on 20 May 2023 reflects the way in which the grouping’s agenda and that of the Indian-led G20 are strongly interconnected. There is specific reference to debt sustainability, as well as digital public infrastructure and the Indo-Pacific’s need for resilient infrastructure. It further refers to New Delhi hosting the QUAD Green Hydrogen Partnership (28).

Despite its recent drift towards the United States, India has still managed to be perceived among the countries of the Global South as an assertive and defiant power, holding its ground as a symbol and torchbearer of decolonisation. New Delhi has become particularly vocal in its calls for reform of multilateral institutions and the need for ‘course correction’. During this year´s Voice of the Global South Summit, Indian External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar described the United Nations as a ‘frozen 1945-invented mechanism’ with ‘some powers … singularly focused on their own advantage, to the exclusion of the well-being of the international community’ (29). This critique of the existing multilateral order led by the traditional powers is not exclusive to India. It is common to an emerging world conglomerate, including both Russia and China, the latter two enjoying permanent membership of the UN Security Council (UNSC) nonetheless.

Despite its criticism of the existing multilateral system, India has been skilful at occupying the middle ground between the traditional/developed powers and the emerging powers that contest the current international order. Consequently it is perceived positively by Western powers, affording it potential security and geo-economic guarantees to counterbalance Chinese influence in the Indian Ocean: the outcome of Modi’s June 2023 trip to the United States, described below, is proof of this. In parallel, New Delhi remains strongly invested in fostering mutually beneficial multilateral cooperation with developing countries. China’s discourse is similar in this regard. There are growing tensions within the BRICS, with China seeking to expand its influence. The recent BRICS Summit in South Africa culminated with six new members being admitted into the grouping (30). Frictions have also flared up among the emerging G20 members as attested by China’s and Saudi Arabia’s refusal to attend the G20 Tourism Working Group Summit in Jammu and Kashmir. Indian policymakers’ greatest fear is not managing to deliver a joint communiqué following the upcoming G20 Leaders’ Summit in September 2023 due to internal disagreements on Ukraine. The confirmed absence of Putin and Xi at the Summit indicates a likely lack of consensus.

New Delhi’s reluctance to publicly criticise Russian actions is nothing new, as seen in 2014 with Russia’s annexation of the Crimean Peninsula and New Delhi’s abstention from a UN General Assembly (UNGA) vote condemning it (31). However, as the war drags on without an end in sight, India has been struggling to maintain its ‘non-aligned’ position both vis-à-vis its ‘like-minded’ partners and Russia. New Delhi continues to export Indian-refined Russian oil while providing humanitarian assistance to Ukraine, and advocating in favour of the need to respect territorial integrity and the sovereignty of nation-states (32). Modi’s remarks to Putin during the SCO Samarkand Summit in September 2022, noting how this was not the time for war, did not fall on deaf ears (33). While India and Russia share their strategic views on how the international system should be organised – with regard to spheres of influence and multipolarity – they differ on their approach to the international rules-based order (34).

Since taking over the G20 chair in December 2022, New Delhi has sought to use the G20 forum to pressure Russia to stop the war, as well as to counterbalance China (35). The caveat lies in the fact that while New Delhi sees Moscow as a useful pole to counterbalance China’s leverage, Russia sees India and China as counterweights to US hegemony (36). The growing proximity between Beijing and Moscow is a source of concern for New Delhi while some accuse India of becoming too close to the United States. The growing strategic closeness of Russia and China has been explicitly formulated in the Joint Statement issued by the two countries as a ‘friendship between the two States [that] has no limits, [where] there are…no “forbidden” areas of cooperation’ (37). This remains a core concern for New Delhi.

In its interactions with the traditional powers, India has set interests, namely, to keep the global commons – outer space, cyberspace and maritime security – free of any single power’s dominance, as well as open and secure. As part of this vision, New Delhi has been actively pursuing new defence partnerships with a spillover into critical and emerging technologies. The rapprochement with Washington is noteworthy considering that US-India relations have historically fluctuated. In the past few years, India has signed a series of foundational defence arrangements with the United States, which has had strong implications for Indian access to encrypted communication and defence information exchange (38).

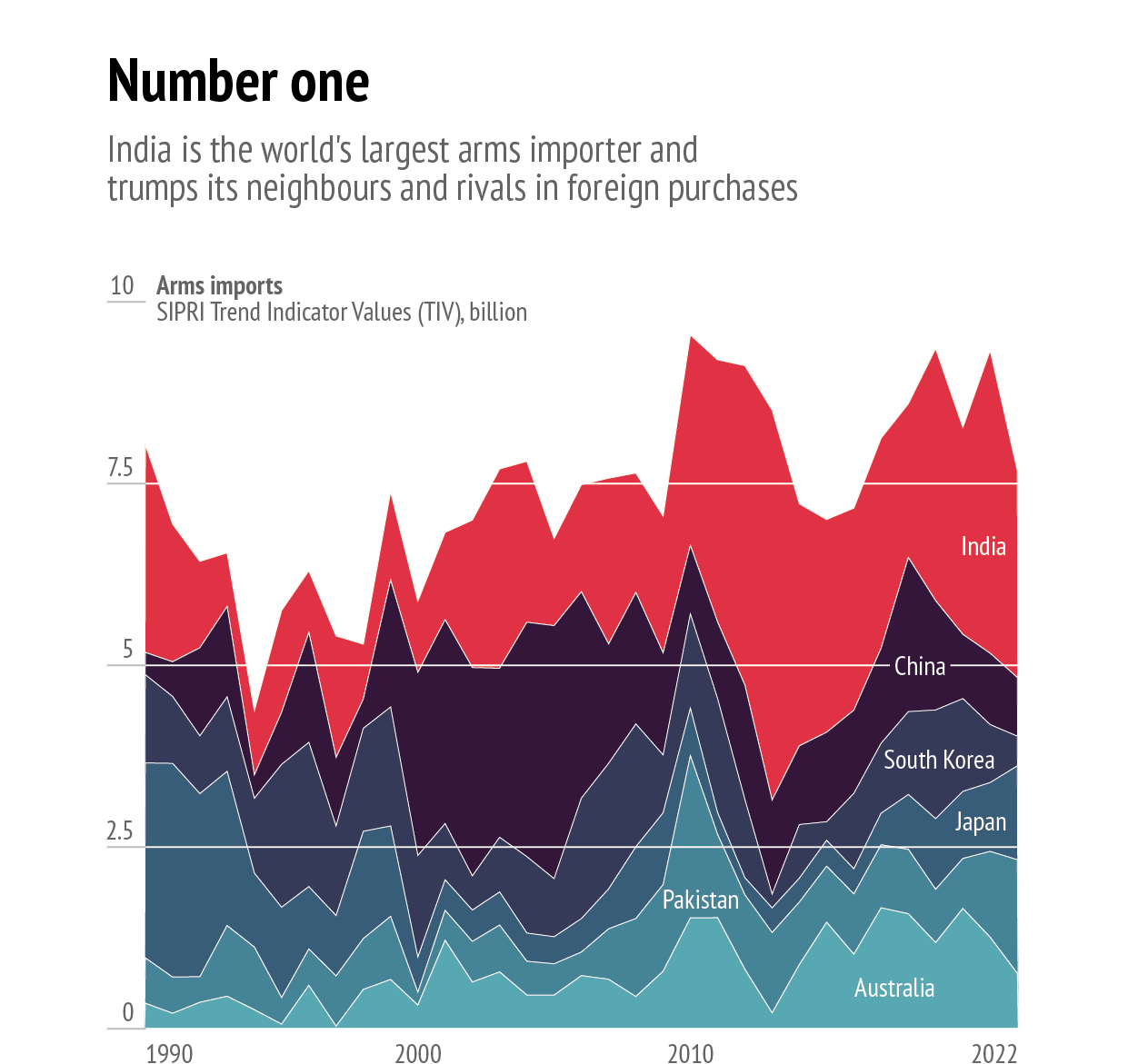

The two countries have become ‘trusted technology partners’ as part of the US-India Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technologies (iCET), officially launched earlier this year. This has opened the door to bilateral strengthening of quantum communications, defence opportunities, building a semiconductor ecosystem in India and exploring commercial space opportunities (39). Modi’s official visit to Washington in June 2023 aimed to deepen the US-India Comprehensive Global and Strategic Partnership (40). Washington is keen to reduce India’s dependence on Russia’s defence industry, and make sure to have New Delhi on its side in case of a Taiwan crisis spiralling out of control (41). Modi, for his part, would like to transform India from being the world’s largest weapons importer to an arms producer (42), thus acquiescing to India-US co-production of advanced defence systems and collaborative research (43). The Japanese-Indian partnership is also growing, as evidenced by New Delhi’s recent presence in Hiroshima and the Japanese prime minister’s official announcement of its new Indo-Pacific strategy in Delhi. Both countries, together with Australia, best represent the leading ‘like-minded’ partners in Asia.

Caveats and opportunities for EU-India minilateralism

We live in an environment where liberal principles of economic interdependence are increasingly being curtailed for national security reasons. Guaranteeing secure and resilient supply chains, access to critical and emerging technologies as well as basic energy supplies have become widespread national concerns. A common concern for both the EU and India is having to position themselves vis-à-vis an increasingly antagonistic US-China relationship. The threats arising from this situation could be managed under minilateral arrangements, assuming there is a shared perception of the threat and of how to deal with it. While there have been recurrent attempts at conveniently packaging both the EU and India as ‘like-minded’ partners, reality proves otherwise.

Data: SIPRI, 2023

The EU remains a strong normative defender of liberal values – both politically and economically – and of the existing rules-based and post-World War II multilateral order. This has not prevented it from donning the mantle of geopolitical leadership in response to current shifts in the global balance of power and the emergence of China and Russian as alternative powers in today’s world order. President von der Leyen’s Commission has reacted with unprecedent joint European defence procurement and protectionist mechanisms to the weaponisation of trade, technology security and the first inter-state war on European soil since World War II. The EU’s recent launch of its Economic Security Strategy epitomises this more robust posture (44). The current conjuncture and challenges to the world order are likely to push the EU towards an increasingly pragmatic approach.

Indian Foreign Affairs Minister Jaishankar’s insistence on shifting gears towards a ‘just in case’ (vs. ‘just in time’) attitude towards international economic cooperation and globalisation speaks to a similar concern regarding economic interdependence. There is additional resistance on the part of Indian officials towards what are being described as anachronistic Bretton Woods institutions and an obsolete UNSC structure, as the halving of India’s Union Budget allocation to the UN for 2023-24 shows (45). This mistrust in leading international institutions has resulted in New Delhi preferring minilateral arrangements with a regional and/or sectoral focus, mostly on maritime security, connectivity and infrastructure arrangements.

The recently created India, Israel, United Arab Emirates and US (I2U2) arrangement is an exception since it combines extra-regional countries with a multi-sectoral approach. India is further geared towards bringing together emerging countries under various arrangements, be it the BRICS, India-Brazil-South Africa (IBSA) or the SCO. But this provides only limited scope for an innovative minilateral space between the EU and India. There is, however, room for manoeuvre in arrangements such as the G20, ideally poised to act as a bridge between the developed and developing world in a more efficient and legitimised forum.

There are also issue area-based minilateral arrangements, such as those focused on climate change, global health, debt sustainability or cybersecurity that could provide much-needed common ground. New Delhi was left out of the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP) with the United States and ten other partners, including the EU, to begin with; Modi’s recent visit to Washington changed that (46). India possesses the world’s fifth-largest reserve of rare earth minerals but lacks sufficient exploration and manufacturing capability; it has started by identifying a list of critical raw minerals based on the EU’s methodology (47). The EU too has come up with its own roadmap this year towards securing a sustainable supply of critical raw materials (48). This is an issue area with scope for collaboration considering the centrality of critical raw materials for key strategic sectors including clean energy, the digital industry, transport, aerospace and defence. Countering China’s dominance in supply chains related to renewables, in particular solar energy and battery storage, is a clear shared interest between the EU and India (49).

There is wide scope for future minilateral cooperation on issues related to maritime security, such as the existing loose trilateral security arrangement between the US, Japan and India as demonstrated by the biannual Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise and annual Malabar exercise – resulting in joint naval, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief exercises (50). Another example is the Australia-Japan-India trilateral launch of a Supply Chain Resilience Initiative (SCRI) that dates as far back as October 2020. Following the AUKUS hiatus, the India-Australia-France trilateral partnership has revived its quest to counterbalance Chinese economic and military expansion in the South China Sea, as well as across the Southern Pacific (51).

The provision of digital public infrastructure in the health and agricultural sectors is high on New Delhi’s agenda, as noted during multiple G20 summits. Global health issues and food security are strong EU concerns too. The I2U2 provides an interesting blueprint of a minilateral arrangement that the EU could aim to replicate vis-à-vis India. It is a platform that brings together a set of countries with shared objectives, not necessarily geographically contiguous or burdened with legally-binding obligations, and potentially divergent interests beyond the areas in which they are cooperating (52). The I2U2 aims to implement economic cooperation projects driven by private industry with the role of government limited to assisting and facilitating implementation. This is also an EU Global Gateway goal, against the backdrop of an existing EU-India Connectivity Partnership launched in May 2021.

Conclusion

India’s current normative positioning and domestic conjuncture have had a strong impact on its desire to capitalise on a hyped-up G20 role. Beyond this arrangement, New Delhi’s quest for minilateralism on a regional and issue-based level reflects its international aspirations and transactional approach to the current world order. India has been skilful at navigating the tricky ‘tightrope’ between the ‘like-minded’ and ‘non-like-minded’ thus far, as its stance towards the Russian War in Ukraine shows. There are no guarantees of how long it can remain geo-strategically unscathed, however. New Delhi must maintain consistency in its foreign policy approach in an uncertain and shifting world order. The EU, for its part, should consider adopting a more pragmatic approach in its minilateral relationship with India, making sure to emphasise its alignment along issue-based common interests over a values-based discourse.

References

1. Chatterjee Miller, M. and Harris C., ‘Modi’s marketing muscle’, Foreign Policy, 20 April 2023 (https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/04/20/india-modi- g20-presidency-pr-marketing-elections/?utm_source=PostUp&utm_ medium=email&utm_campaign=South%20Asia%20Brief%20OC&utm_ term=84432&tpcc=South%20Asia%20Brief%20OC).

2. According to one commentator, ‘minilateralism is characterized by bringing to the table the smallest number of countries needed to have the largest possible impact on solving a particular problem’. See Naim, M., ‘Minilateralism’, Foreign Policy, 21 June 2009, pp. 135-6 (https:// foreignpolicy.com/2009/06/21/minilateralism/).

3. G20 India, ‘Sherpa Track’, 2023 (https://www.g20.org/en/workstreams/ sherpa-track/).

4. G20 India, ‘Logo and Theme’, 2023 (https://www.g20.org/en/g20- india-2023/logo-theme/).

5. Speech by Nirmala Sitharaman, Indian Minister of Finance, when presenting the Union Budget 2023-24, 1 February 2023 (https://www. indiabudget.gov.in/doc/budget_speech.pdf).

6. Ashley J. Tellis explains the difference between ‘great’ and ‘leading’ powers from a realist perspective in that the former are genuine poles in international politics, while the latter are, at best, ‘system shapers’. See Tellis, A., ‘Introduction - Grasping Greatness: Making India a leading power’, in Tellis et al. (eds.), Grasping Greatness: Making India a leading power, India Viking, New Delhi, 2022, p. 13.

7. Ibid, p.17.

8. See Hall, I., Modi and the Reinvention of Indian Foreign Policy, Bristol University Press, Bristol, 2019, p. 39.

9. PM Modi’s speech at inauguration of New Parliament House (English Version), 28 May 2023 (https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=Zrt2POplGGw).

10. According to a recent World Bank report, poverty in India has declined over the last decade (2012-22) but not as much as was thought initially, based on projections by the National Accounts System (NAS) due to a lack of official data since 2011. Inequality remains a challenge with India ranking among the lowest in the Asia Pacific with a GINI index of 35.7 in 2017 (latest available data), according to the World Bank. See Sinha Roy, S. and Van der Weide, R. ‘Poverty in India has declined over the last decade but not as much as previously thought (English)’, World Bank, 2022 (https://documents.worldbank.org/en/ publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099249204052228866/ idu0333e60f901267045600be83093783b77e67a) and Ghosh, N. and Sarkar, D., ‘Beyond poverty alleviation: Envisioning inclusive growth in the BRICS countries’, Observer Research Foundation (ORF), p.16 (https://www.orfonline.org/research/beyond-poverty-alleviation/).

11. ‘India ranks 132 on the Human Development Index as global development stalls’, UNDP, 8 September 2022 (https://www.undp.org/ india/press-releases/india-ranks-132-human-development-index- global-development-stalls).

12. Tellis provides comparative data from different sources on predicted GDP per capita data by 2050. Grasping Greatness: Making India a leading power, op. cit., p. 24.

13. Arvind Subramaniam highlights India’s unique economic development model that specialises in comparative advantages that are usually the preserve of rich countries, i.e. services, exporting skills via outward FDI, and its success at sustaining democracy despite being a lower-middle income country and substantial social cleavages (in terms of religion, region and skills level). See Subramaniam, A., ‘The precocious Indian development model and its future’, Centre for Global Development (CGD), 14 May 2014 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Iu35lAStz0w).

14. ‘Real GDP Growth, Country Indicators India’, IMF Datamapper (https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDP_RPCH@WEO/ IND?zoom=IND&highlight=IND).

15. Grasping Greatness: Making India a leading power, p. 24, op. cit.

16. The BJP Manifesto 2014 refers to India as Vishwaguru (Teacher of the World) and the need to spread its ancient wisdom and heritage. BJP, Election Manifesto 2014, p. 40 (https://library.bjp.org/jspui/bitstream/123456789/252/1/bjp_lection_manifesto_english_2014.pdf).

17. ‘National statement by Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the Summit for Democracy’, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, 10 December 2021 (https://www.mea.gov.in/Speeches-Statements. htm?dtl/34637/National_Statement_by_Prime_Minister_Narendra_ Modi_at_the_Summit_for_Democracy).

18. Sullivan de Estrada, K., ‘What is a vishwaguru? Indian civilizational pedadogy as a transformative global imperative’, International Affairs, Vol. 99, No 2, 2023, pp. 433-455.

19. G20, ‘Third meeting of G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors (FMCBG) under the Indian G20 Presidency 17-18 July 2023, Gandhinagar, Gujrat’ (https://www.g20.org/pt/media-resources/press- releases/july-2023/fmcbg-gujrat/).

20. ‘Indian Ministerial Delegation: Press Remarks following India- EU TTC Meeting’, Ministry of External Affairs, India, 16 May 2023 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XcEJx0J7QUE).

21. India Stack defines itself as ‘the moniker for a set of open APIs and digital public goods that aim to unlock the economic primitives of identity, data, and payments at population scale. This vision can be applied to any developed or emerging country’: see India Stack website (https://indiastack.org/).

22. Koga, K. and Nachiappan, K., ‘Forging a G7-G20 nexus: Cooperation between Japan and India’, 9 Dash Line, 15 May 2023 (https:// www.9dashline.com/article/forging-a-g7-g20-nexus-cooperation- between-japan-and-india).

23. Prime Minister Modi’s Atmanirbhar Bharat policy launched during the pandemic emphasises economic self-sufficiency based on privatising unprofitable state-owned enterprises and supporting domestic companies across sectors like agriculture, health, manufacturing and defence. See . Government of India, ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ (https:// aatmanirbharbharat.mygov.in/).

24. ‘India-Japan Joint Statement during the visit of Prime Minister to Japan’, Prime Minister’s Office, India, 11 November 2016 (https://pib.gov.in/ newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=153534).

25. Council for Strategic and Defense Research (CSDR), DIPTEL #22 newsletter, 3rd week of April 2023.

26. Menon, S., India and Asian Geopolitics: The past, present, Penguin Random House India, Haryana, India, 2021.

27. Ibid, p. 360.

28. The White House, ‘QUAD Leaders’ Joint Statement’, Hiroshima, 20 May 2023 (https://www.pm.gov.au/media/quad-leaders-joint-statement).

29. Bhattacherjee, K., ‘General Assembly divided over UN reforms, says Csaba Korosi’, The Hindu, 30 January 2023 (https://www.thehindu.com/ news/national/general-assembly-divided-over-un-reforms-says- csaba-korosi/article66451621.ece).

30. Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have been admitted as new members. See ‘XV BRICS Summit Johannesburg II Declaration’, 23 August 2023 (https://brics2023.gov.za/wp-content/ uploads/2023/08/Jhb-II-Declaration-24-August-2023-1.pdf).

31. Basrur, R. and Dave, B., ‘India, Russia and the Ukraine crisis’, IDSS Paper No 11/2022, RSIS, 2 March 2022 (https://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/ uploads/2022/03/IP22011.pdf).

32. CSDR, DIPTEL #22, op. cit.

33. Mamatkulov, M., ‘India’s Modi assails Putin over Ukraine war’, Reuters, 16 September 2022 (https://www.reuters.com/world/china/putin-xi- speak-summit-uzbekistan-2022-09-16/).

34. Lalwani, S. et al., ‘The influence of arms: Explaining the durability of India–Russia alignment’, Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, Air University Press, 15 January 2021.

35. CSDR, DIPTEL #23, 4th week of April 2023.

36. ‘The influence of arms: Explaining the durability of India–Russia alignment’, op. cit.

37. The Kremlin, ‘Joint Statement of the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China on the International Relations Entering a New Era and the Global Sustainable Development’, 4 February 2022 (http://www. en.kremlin.ru/supplement/5770).

38. For details on the three security arrangements signed between the US and India, see US Department of State, ‘US Security Cooperation with India’, 20 January 2021 (https://www.state.gov/u-s-security- cooperation-with-india/).

39. Chaudhuri, R., ‘What is the United States-India Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technologies (iCET)?’, Carnegie India, 27 February 2023 (https://carnegieindia.org/2023/02/27/what-is-united-states-india- initiative-on-critical-and-emerging-technologies-icet-pub-89136).

40. The White House, ‘Joint Statement from the United States and India’, 22 June 2023 (https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements- releases/2023/06/22/joint-statement-from-the-united-states-and- india/).

41. CSDR, DIPTEL #30, 3rd week of June 2023 and CSDR, DIPTEL #33, 1st week of July 2023.

42. ‘Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2022’, SIPRI Fact Sheet (https:// www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2023-03/2303_at_fact_sheet_2022_ v2.pdf).

43. The White House, ‘Joint Statement from the United States and India’, op cit.

44. European Commission, ‘An EU approach to enhance economic security’, 20 June 2023 (https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ IP_23_3358).

45. Ministry of Finance, India, ‘Expenditure Profile 2023-24’, February 2023 (https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/doc/eb/stat21.pdf).

46. The White House, ‘Joint Statement from the United States and India’, op cit.

47. Indian Ministry of Mines, ‘Critical Minerals for India’, June 2023 (https:// mines.gov.in/admin/storage/app/uploads/649d4212cceb01688027666. pdf).

48. European Commission, ‘Critical raw materials: ensuring secure and sustainable supply chains for EU’s green and digital future’, 16 March 2023 (https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ ip_23_1661).

49. Ibid.

50. ‘US Security Cooperation with India’, op. cit.

51. Kapur, Commodore L., ‘Reviving India-France-Australia trilateral cooperation in the Indian Ocean’, DPG Policy Brief, Delhi Policy Group, 18 July 2022 (https://www.delhipolicygroup.org/publication/policy-briefs/ reviving-india-france-australia-trilateral-cooperation-in-the-indian- ocean.html).

52. Suri, N., ‘I2U2 and the Case for Minilaterals’, in Suri, N. and Taneja, K. (eds.) I2U2: Pathways for a New Minilateral, ORF, New Delhi, 2023, pp. 9-12.