You are here

EU-GCC relations

Introduction

The six member states of the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf (commonly known as the Gulf Cooperation Council, or the GCC) stand at a pivotal juncture amid shifting superpower dynamics. An ascending China and a resurgent Russia in the region coupled with a perceived US retreat from the Middle East add to this changing landscape, increasing the GCC’s need to hedge its bets.

Against this backdrop of uncertainty, the EU and the GCC have long recognised the need to elevate their partnership to a higher level. Their motivations are clear: regional security, energy cooperation, economic diversification, and meeting the aspirations of their young populations. However, despite these efforts, the EU-GCC partnership has yet to achieve its full potential. The reasons for this are manifold, rooted in institutional differences, conflicting interests and divergent values. The two sides lack a deep understanding of each other’s perspectives and ambitions, leading to largely misaligned goals and a disconnect in decision-making processes.

While a more productive partnership is attainable, it hinges on addressing these underlying issues and establishing a framework anchored on three elements: identity, mandate and process.

The wrong start

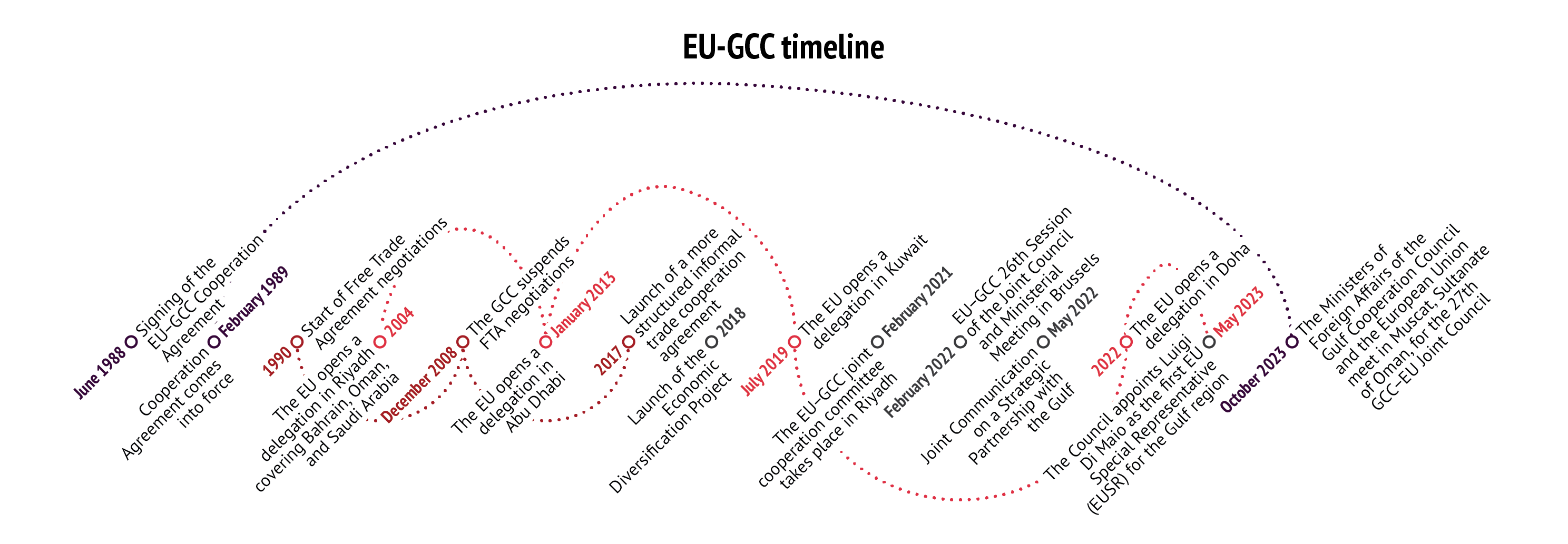

The first hurdle that the EU and GCC need to overcome is their different identities, especially their institutional frameworks. The GCC is an intergovernmental organisation, whereas the EU is a supranational body. Each GCC member state may act independently regarding strategic issues, such as foreign policy and governance. At the EU level, the supranational European Commission conducts international trade negotiations under the member states’ mandate. There is no such equivalent at the GCC level. The Free Trade Agreement (FTA) has not materialised after almost 34 years of negotiations, partly due to the institutional differences between the two blocs.

The FTA aimed to secure EU access to energy resources and improve EU access to GCC markets, while the GCC anticipated increased trade, better export access and an influx of European capital to boost economic diversification (1). The EU required the creation of a customs union that would have prevented trade diversion from GCC countries with higher customs rates to those with lower ones.

Bureaucratic inefficiencies and structural economic problems slowed progress. It took the GCC 11 years to create the GCC Customs Union, which was inaugurated in January 2003. In 2008, citing ‘the absence of any progress in the negotiations’ (2), the GCC unilaterally halted the negotiations while agreeing to continue consultations until reaching a common ground to resume negotiations. There were several reasons for this impasse, including the EU’s adoption of higher carbon taxes and export duties; GCC delays in setting up a customs union; and frictions over some of the agreement’s provisions, including the ‘human rights clause’ (3).

The EU-GCC relationship has recently come under renewed strain following the war on Gaza.

The FTA could have been groundbreaking, but is unlikely to be signed due to the GCC states’ growing foreign policy assertiveness and the ‘China factor’. China is the largest trading partner of the GCC states, accounting for over 15 % of their total trade. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s flagship infrastructure project, has played a major role in expanding economic ties between China and the Gulf, with investments in ports, railways and other infrastructure, while the GCC supplied 41% of China’s energy supplies in 2022.

Whatever works

The second impediment to an effective EU-GCC partnership is their dissimilar ‘values’. To surmount the hurdle of the FTA, the two partners have tried to diversify the scope of their relations. Consequently, they established Working Groups in the fields of industrial cooperation, energy and the environment, and in 1996 they added a ‘decentralised track’ aimed at promoting ties between non-governmental organisations and civil societies in the business, media and higher education sectors through co-financing (4).

The EU eventually shifted its approach in the early 2000s towards a more balanced strategy that combines decentralisation with state-to-state engagement. Any advancement in this area would have required active civil society involvement. But restrictions on civic institutions remain tighter in several GCC states than elsewhere in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) (5).

Lost in translation

The third impediment to constructive EU-GCC relations has been their conflicting priorities and interests. Security is a salient theme across the GCC, especially given the volatility of the Middle East region. The EU cannot independently and decisively act as a security guarantor for the GCC like the US. This limitation has been a significant barrier to stronger EU-GCC relations.

Nevertheless, the EU has expanded its Coordinated Maritime Presence (CMP) framework to include the north-western Indian Ocean, demonstrating its commitment to maritime security in the Gulf region. This has yielded some results on maritime security. On 30 January 2023, the Coordinated Maritime Presences in the North-West Indian Ocean (CMP NWIO) organised a symposium to promote this new EU concept and enhance maritime cooperation between the EU and Omani naval forces.

The two actors, however, cannot always reconcile their geopolitical and security interests and have recently been poles apart on some issues. Examples are numerous: none of the GCC states aligned with the EU’s stance regarding the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Furthermore, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates disagree with the imposition of sanctions against Russia and are actively working to strengthen their economic and financial ties with Russian entities.

Regarding Syria, the EU refuses any contact with Bashar al-Assad’s regime, while the Arab League welcomed al-Assad at its last summit in May 2023, bringing Syria back into the fold of the 22-member league after a 12-year suspension.

The EU-GCC relationship has recently come under renewed strain following the war on Gaza, particularly due to differing stances on a ceasefire and growing perceptions of Western double standards in the Arab world. While the West swiftly condemned and sanctioned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, it has been more muted in its response to Israel’s actions in Gaza. To underline the EU’s impartiality, HR/VP Josep Borrell embarked on a diplomatic tour of the Middle East, including the Gulf.

The situation is further complicated by rising Chinese influence in the GCC’s geopolitical sphere, most evident in the Beijing-brokered Iran-Saudi Agreement of March 2023, as well as Beijing’s stance on the Gaza war. Chinese President Xi Jinping has criticised Israel’s ‘collective punishment’ and continuously called for a ceasefire.

Undoubtedly, the aforementioned geopolitical divergences will continue to pose substantial challenges to advancing the EU’s strategic alliance with the Gulf.

The way forward

Despite recent EU-GCC efforts to strengthen ties, their success is uncertain due to identity, mandate and process gaps. A productive relationship hinges on addressing these three key elements.

Identity

Mutual understanding requires both sides to invest in learning about each other’s institutional frameworks and internal dynamics at the state and societal levels. This ongoing effort is crucial for effective cooperation. Amidst the complexities surrounding the formation of a collective EU or pan-Gulf vision and the evolving self-images of individual member states, it is crucial to acknowledge the dynamic self-perception within both European and Gulf states. The rapid pace of change often goes unnoticed or disregarded in policy circles, leading to misinterpretations and ineffective approaches (6).

In recent years, the EU has wisely increased the number of delegations in GCC member states (7). That should be followed up with efforts to engage more closely with local civil society. Conducting regular surveys and engaging with citizens through thematically-focused discussion groups will raise awareness of citizens’ views, thus leading to sound, evidence-based policymaking.

Both regions exhibit different worldviews at the state and societal levels. Capturing the full range of views is unrealistic and unnecessary. However, policy discussions and resultant decisions must accommodate variations between European and Gulf states and the shifting currents of public opinion in the two regions.

Mandate

The numerous meetings between the two parties have resulted in ambitious yet somewhat impractical to-do lists. The various memoranda are an overreach – the scrupulous attempt to cover every item of concern imaginable to both sides is exhausting and counterproductive. It may score quick wins, reinforcing the alignment of the two sides on the political issues under examination. But the main constituents, the people, will not feel their impact.

The vast scope of existing projects, as exemplified by the October 2023 Statement with its 13 diverse themes, reflects this overambitious approach (8). While comprehensiveness is admirable, focus and deliverability should take precedence. Given the renewed momentum in EU-GCC relations, it is prudent to adopt a measured, incremental approach. Concentrating on two or three projects, rather than dispersing efforts across multiple initiatives, will foster a deeper understanding and boost confidence in the mutual benefits accruing from the relationship.

The EU and GCC must identify areas of collaboration that reconcile state and societal interests while considering their respective engagements with other powers. While the EU has a strong presence in security and trade, it should not seek to compete in these areas traditionally dominated by the US or China. Instead, identifying a niche sector for prioritised collaboration would be more advantageous. Climate change, clean energy and green transition should be a primary focus area (9). The EU has the technology and know-how, while the GCC has made the public commitment and the investments necessary to manage the energy transition and the delicate shift away from fossil fuels (10).

A second promising project is underway: maritime security. Steps already taken through the CMP will complement other Gulf partnerships with the US. It will also offer the GCC a flavour of the EU’s approach, capitalising on its long tradition in the field.

Finally, people-to-people exchanges are best fostered by amplifying access. Accelerating Schengen visa waivers for GCC citizens and encouraging cultural exchanges in education is a good start. The Erasmus+ and Erasmus Mundus Joint Masters programmes are valuable yet limited in scope (11). A more marketable educational initiative is necessary: one that earmarks funds for GCC participation and eases programme entry requirements.

Process

Neither understanding one another better nor focusing on a few key projects will yield sustainable results without an agile and well-defined process guiding the EU-GCC relationship. Both entities, and especially the EU, are elaborate bureaucratic organisations. For momentum to continue unimpeded, officials should resort to exemptions to bypass the processes in place, even if only for a transitional period until the relationship delivers concrete and measurable outcomes. The two figures central to the proposed process have recently taken up their appointments: the first EU Special Representative to the GCC, Luigi Di Maio, and the GCC ambassador to the EU, Abdulaal Al-Qenaei. Both will work in close collaboration after receiving the go-ahead to act on behalf of the two entities.

A joint team, led by the newly-appointed EU and GCC representatives, would bolster the partnership and foster mutual understanding. A core group and a live dashboard would monitor key performance indicators for proposed initiatives. Outreach and media engagement would raise awareness, engagement and accountability. This process reset aligns with the EU’s decentralised approach and enhances understanding of both sides’ priorities.

The EU-GCC relationship has much potential. Setting it on the right track requires urgent attention to questions of identity, mandate, and process.

References

1. Ghafar, A.A. and Colombo, S., ‘EU-GCC relations: The path towards a new relationship’, Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, Policy Report No. 2, March 2020 (https://www.kas.de/documents/286298/8668222/200401+Policy+Report+No+2+GCC-EU+Path+towards+a+New+Relationship.pdf/25e95278-7689-2ec2-0b14-e27197b49969?version=1.1&t=1585898593194).

2. GCC official website, ‘Regional Cooperation and Economic Relations with other Countries and Groupings’ (https://www.gcc-sg.org/en-us/CooperationAndAchievements/Achievements/RegionalCooperationandEconomicRelationswithotherCountriesandGroupings/Pages/main.aspx).

3. European Parliament, ‘Human rights in EU trade agreements: The human rights clause and its application’, Briefing, July 2019. (https:// shorturl.at/bemwK).

4. Kostadinova, V., ‘What is the status of the EU-GCC relationship?’, GRC Gulf Papers, 2013, pp.6-7 (https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/167338/EU- GCC_9227.pdf .pdf).

5. Gulf House, Political Participation Index in the GCC countries, 2023 (https://gulfhouse.org/gccppi-en/).

6. Jones, C., ‘European Identity and Crisis’, ES Think Tank, 14 February 2023 (https://esthinktank.com/2023/02/14/european-identity-and-crisis/); Karolak, M., ‘Gulf countries: The struggle for a common identity in a divided GCC’, ISPI, 13 May 2019 (https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/gulf-countries-struggle-common-identity-divided-gcc-23091).

7. EEAS, ‘Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and the EU’, 3 August 2021.

8. Council of the EU, ‘Co-Chairs’ Statement of the 27th GCC-EU Joint Council and Ministerial Meeting,’ Press Release, 10 October 2023 (https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/10/10/co-chairs-statement-of-the-27th-gcc-eu-joint-council-and-ministerial-meeting/).

9. This is in line with the EU GCC Clean Energy Network II (CENII) project launched in 2015. Yet there could be more streamlining and support for the initiative: EU-GCC Clean Energy Technology Network, ‘Working Areas’ (https://www.eugcc-cleanergy.net/workinggroups). One encouraging recent example is Saudi-Greek energy collaboration targeted at long-term ‘cheaper green energy’. See: ‘Greece, Saudi Arabia to look at linking their power grids’, Reuters, 27 September 2023 (https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/greece-saudi-arabia-look-linking-their-power-grids-2023-09-27/).

10. Delegation of the European Union to the United Arab Emirates, ‘European Union and GCC experts come together to discuss energy efficiency in the building sector as a key driver for net-decarbonisation’, 25 October 2022 (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/delegations/united-arab-emirates/ european-union-and-gcc-experts-come-together-discuss-energy- efficiency-building-sector-key-driver_en?s=210). Szalai, M.,‘Can green transition help EU build better relations with the Gulf?’, The Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, 2 December 2021 (https://agsiw.org/can- green-transition-help-eu-build-better-relations-with-the-gulf/).

11. European Commission, ‘Eligible Countries’, Erasmus+ EU programme for education, training, youth and sport (https://erasmus-plus.ec.europa.eu/ programme-guide/part-a/eligible-countries).