You are here

Table of contents

Easing, suspending and phasing out

Introduction

‘Target authorities did not show any signs of flexibility while the sanctions were in place. They did when we started easing the sanctions’. After listening to these words, I raised my eyes from the piece of paper where I was noting them down, and looked at the official seated in front of me with an expression of surprise. Was this a suggestion that sanctions could actually effect a change in the conduct of a target not after their imposition, but once they were eased? I wondered. As a researcher collecting interview material for my study, it seemed unlikely to me that the scholarly community would have missed anything that was key to sanctions success. Still, I left the meeting with an uneasy sense that something might be wrong about the way social science has tended to analyse the phenomenon of sanctions so far. What if, instead of compelling behavioural change in third-country leaderships or the influential elites that support them, sanctions were useful in eliciting concessions in exchange for the easing of restrictive measures? If this was so, it meant that we were focusing on the wrong end of the sanctions exercise – imposition and escalation – rather than on what promised most progress towards compliance: de-escalation and winding down of the measures.

On closer inspection, there may be some truth in the idea that compliance can be promoted through sanctions easing, and most centrally, that this property of sanctions may have been underestimated so far - and consequently, underexploited in policymaking. After sanctions are wielded, we are accustomed to scenarios of tightening, but we rarely hear about the easing of sanctions. This circumstance may feed into allegations of sanctions’ ineffectiveness. The present Brief examines the idea that compliance can be promoted through sanctions easing or relief, or the promise thereof. In order to do so, it points first to some factors that make progress towards compliance unlikely in sanctions situations. Second, it identifies the type of sanctions that the EU applies – targeted sanctions – as particularly suitable for use in de-escalation tactics. Third, it identifies a method of gradual easing that the EU has already been employing to promote target compliance while facilitating the resumption of normal relations – however, in a field institutionally separate from security policy: EU development cooperation partnerships. It then outlines how the gradual easing of sanctions employed in the field of development cooperation can be transferred to the foreign policy realm.

While information on the events motivating sanctions imposition is readily available, little is known about how sanctions can be eased or rolled back.

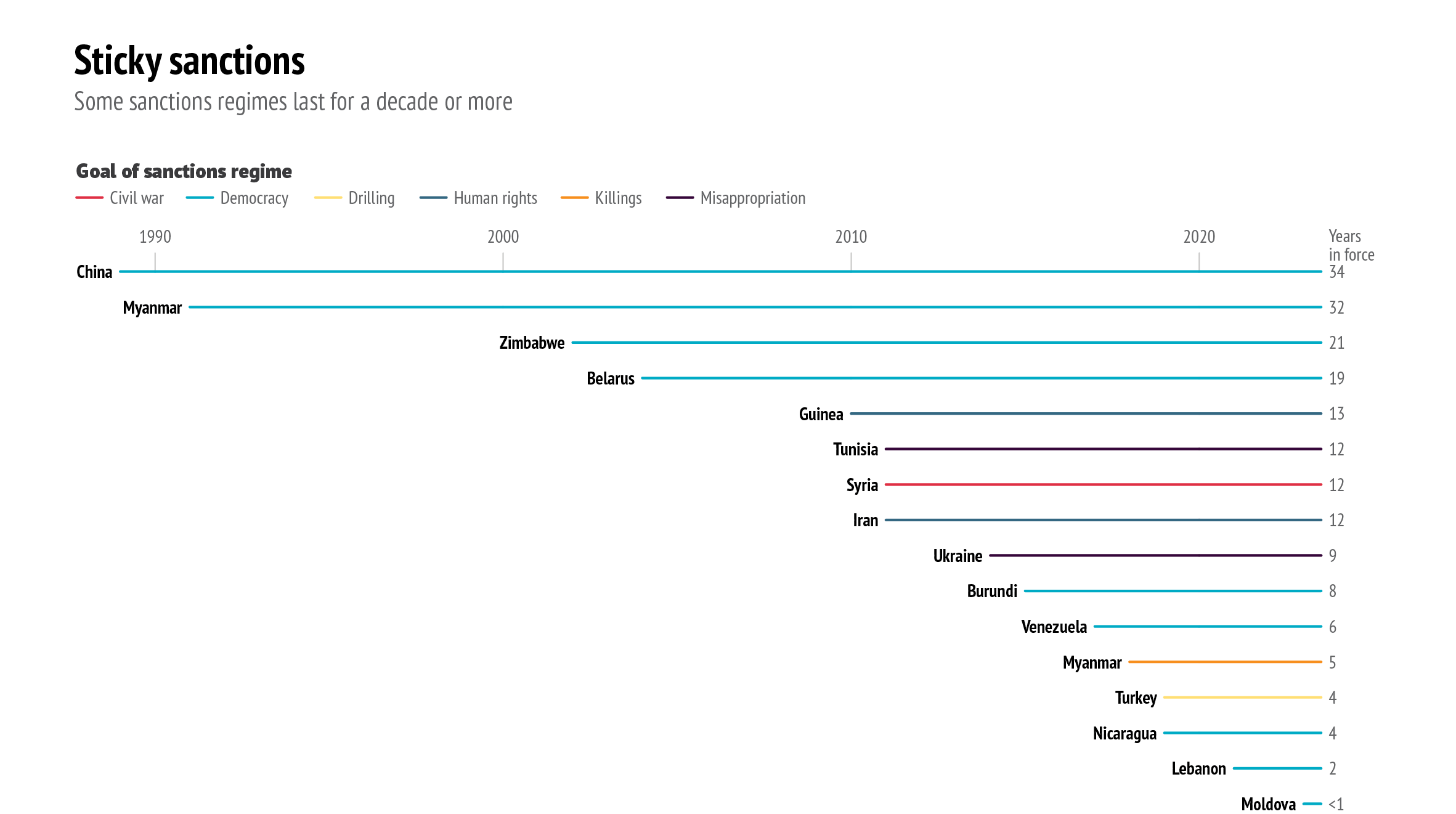

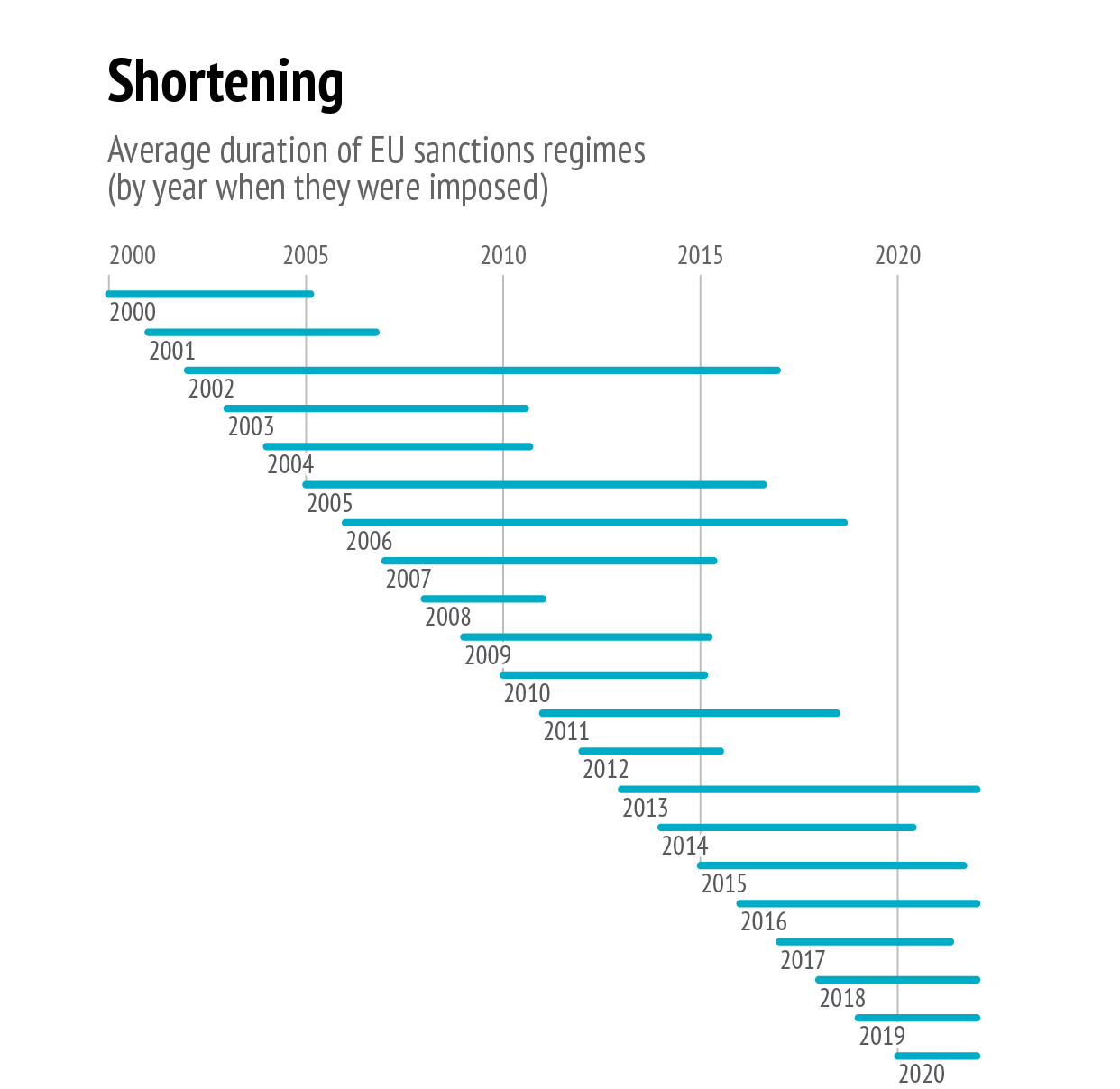

The Brief concludes with some recommendations on how the promise of sanctions easing could be realised. While sanctions relief would be inapplicable in exceptional contexts like the current sanctions operation against Russia over its invasion of Ukraine, which addresses a breach of international law with existential ramifications for the Union (1), it could help bring a number of sanctions regimes that address domestic situations in the target country to a successful conclusion, preventing a protracted and unproductive stalemate. After all, in addition to the sanctions against Russia and the UN-led sanctions regimes, the EU has about a dozen fully autonomous sanctions regimes in force against third countries, some of which have been in existence for one or two decades (2). Efforts to promote the successful resolution of stagnating sanctions regimes are particularly important at a time where global trends show that sanctions episodes tend to be less successful and extend for a longer duration than in the past (3).

The perils of ambiguity

Although sanctions started to acquire visibility in European foreign policy only recently, the EU has Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) since the early 1990s (4). Moreover, the beginning of this sanctions practice pre-dates the institutionalisation of the CFSP as the framework for the adoption of sanctions measures. The way in which sanctions regimes come into being, in the CFSP context and more generally, is well known: speeches, press releases, news stories and official legislation present plentiful information regarding the circumstances surrounding the imposition of sanctions. They detail the incidents that gave rise to the sanctions, the international norms that were violated and, thanks to the routine use of blacklists, the identity of those individuals identified as responsible. However, while information on the events motivating sanctions imposition is readily available, little is known about how sanctions can be eased or rolled back. Sanctions-enactment documents contain standard formulations indicating that sanctions ‘will be kept under constant review’, or that they ‘may be renewed or amended as appropriate’, while stipulating an been resorting to these tools in the framework of its expiry date after which a decision on renewal must be taken. Yet, details of the sort of action required for the sanctions to be eased or lifted are often missing.

NB: This graph displays all EU country sanctions regimes currently in force. It excludes horizontal sanctions regimes, sanctions imposed over the invasion and destabilisation of Ukraine and UN-mandated sanctions regimes.

Data: EU Sanctions Map, 2023

On first inspection, the absence of stipulations permitting the easing of the measures offers maximum flexibility to senders – not having tied its hands, the sender remains free to choose when to relax sanctions. The sender thus retains the liberty to consider itself satisfied with any amount of progress towards compliance. From this viewpoint, keeping sanctions documents free from stipulations on lifting may be conducive to an accommodation with the target since neither party is bound to the completion of any specific action. However, the ambiguity associated with the absence of conditions for lifting can work in the opposite direction: it may lead the target to believe that the sender will make use of its flexibility to deny any progress it may accomplish towards complying with sender goals and leave sanctions in place. Indeed, targets often spread the idea that senders will continue to impose sanctions irrespective of the behaviour of their leadership, presenting the measures as part of a policy that seeks to undermine the country’s prosperity and reputation, rather than as a response to a specific norm violation.

While such discourse can be understood as mere rhetoric geared towards discrediting the sender and rallying the population around the leadership, the possibility that this belief is sincere cannot be discarded. Such belief may be strengthened by the antagonistic dynamics that unfold between sender and target in the course of the sanctions episode, and that often represent the culmination of a long-standing deterioration in bilateral relations. This is particularly likely given that the communication on what specific actions are expected from the target in order for the sanctions to be eased generally occurs behind closed doors. This makes it impossible to observe in which terms expectations are communicated, or whether such communication takes place at all.

Targeted sanctions as an adjustable tool

The tools that the EU traditionally applies as part of its sanctions policy are particularly apt for easing. Due to their targeted nature, they may be easily ratcheted up or relaxed (5). The same is not true for comprehensive embargoes or ‘maximum pressure’ campaigns that entail the deployment of sanctions with the aim of asphyxiating the target’s economy – these are either in force or fully lifted. Targeted sanctions, by contrast, may be graduated. Because they can be applied on different territories, affect a varying number of individuals and entities, and cover certain areas of trade in full or partially, they can be scaled down to reward progress by the target. Nevertheless, in order to maintain an incentive for further cooperation, a reduced version of the sanctions package can be left in force until further progress is achieved. In both EU and UN practice, examples abound of how targeted sanctions can be lifted partially and selectively due to their elastic nature.

Data: Global Sanctions Database, 2023

Arms embargoes, often imposed initially on all parties to a conflict, can be lifted on parties that are effectively implementing a peace agreement, or those who have completed security sector reform. Diplomatic sanctions can be adjusted by allowing embassies to increase their staff, while consulates can be allowed to reopen (6). However, the option of easing sanctions making use of gradual and selective liftings does not per se offer a method for incentivising progress towards compliance with sender goals. There is still a need to design an approach that connects sanctions relief to progress towards compliance with the goals of sanctions. While such an approach is currently missing in the CFSP, a separate realm of EU external relations offers a promising blueprint.

Aid suspension as a sanction

The interruption or limitation of development cooperation between a donor entity and a recipient country – routinely referred to as Official Development Aid (ODA) - is a traditional sanctions tool. Aid sanctions entail the total or partial suspension of assistance offered to a recipient in pursuance of non-economic objectives such as human rights and democracy (7). Aid cut-offs meet the definitional criteria for sanctions: they consist in the deliberate interruption or reduction of a benefit that would otherwise be granted, in response to an illegal or politically undesirable act and in pursuance of a coercive intent, often to persuade recipients to implement political reforms (8). In contrast to classical economic sanctions, aid cut-offs do not restrict trade or finance, but the flow of foreign aid. The practice of aid cuts flourished in the aftermath of the Cold War. As almost all Western donor agencies formally conditioned aid on governance requirements, this period saw aid being cut off with increasing frequency when such requirements were not honoured, leading to a profusion of sanctions over the past few decades.

As one of the main global donors, the EU suspended aid 24 times on political grounds from 1990 to 2009 (9), mirroring a dramatic increase in the global use of economic sanctions (10). The rules governing development assistance provided by the EU to recipient countries located in the African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) area are enshrined in the ACP-EU Partnership Agreement, which has been renewed regularly since its inception (11). Most suspensions have taken place under the iteration of the agreement signed at Cotonou, Benin, which remained in force for two decades (12). The agreement foresaw the respect for human rights, democratic principles and the rule of law as essential elements. According to its Article 96, if the Council of the EU or the recipient country considered that the other party failed to respect any of these principles, it was authorised to invite the party in question to hold consultations on ‘measures to be taken to remedy the situation’ (13). Once the invitation was issued, consultations had to be held within a period of 30 days.

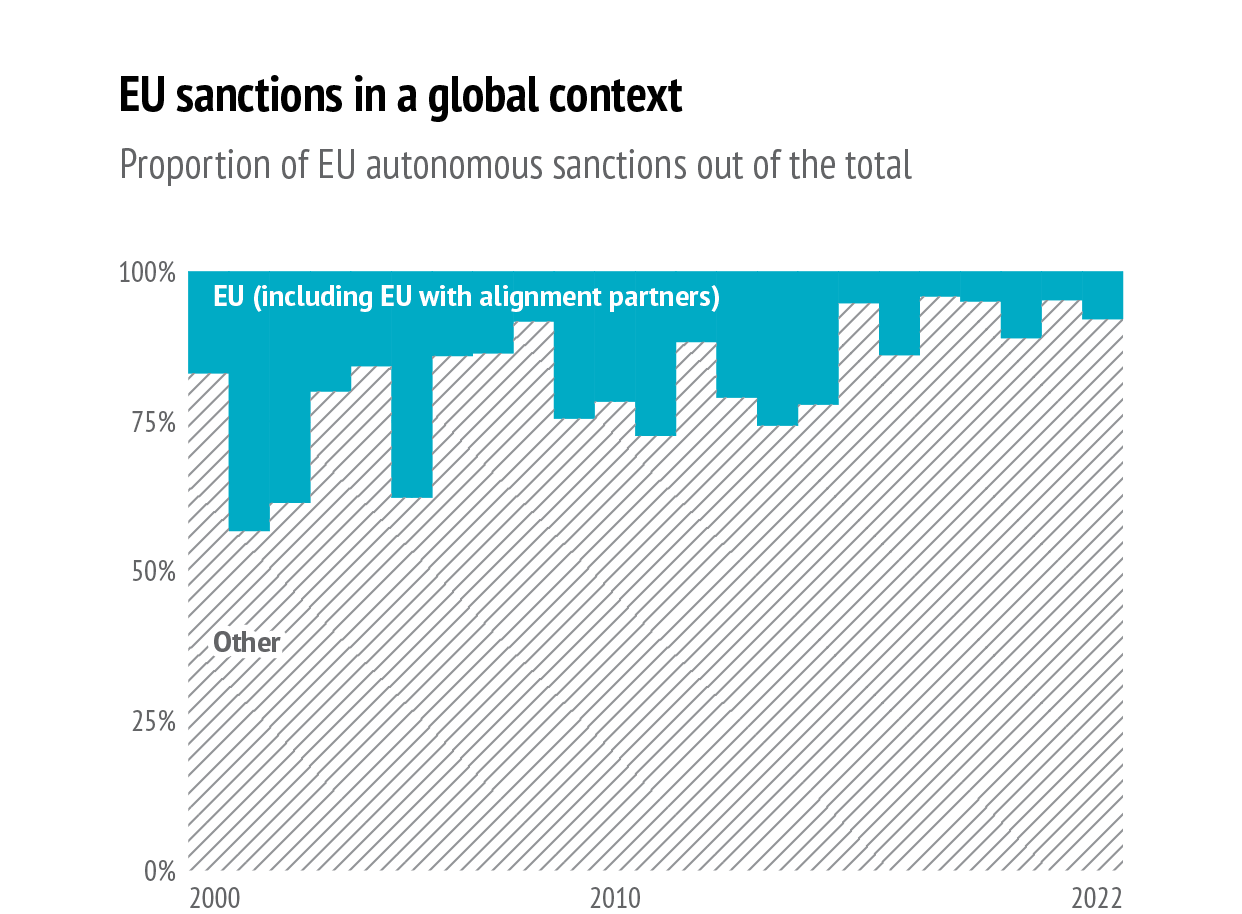

Data: Global Sanctions Database, 2023

In the course of the consultations, both parties strove to negotiate a roadmap with the steps to be taken by both parties in order to reach a solution to the crisis acceptable to both. If a roadmap could be agreed, it was reflected in a decision adopted by the Council of the EU. In the event that consultations failed to lead to a solution acceptable to both parties, measures might be taken that could include the suspension of the agreement and of its benefits, notably the provision of development assistance. While the article granted a great deal of latitude in the selection of measures to be adopted, it stipulated a number of conditions that these had to fulfil: measures should be taken in accordance with international law, and be proportional to the violation. Measures which least disrupt the application of the agreement should be prioritised, with suspension identified as a measure of last resort (14). Furthermore, except for cases of special urgency, consultations under art.96 should be preceded by intensified political dialogue. Art. 96 explicitly stipulated that any measures taken shall be revoked as soon as the reasons for taking them ceased to prevail (15). The Council of the EU reports having invoked art. 96 fifteen times, whereby some countries like Fiji or Guinea-Bissau were invited to consultations on several occasions (16).

Solving the resumption dilemma

Although the suspension practice under art. 96 of the Cotonou Agreement has attracted considerably less attention than sanctions under the CFSP, it is considered more effective in inducing political reform in the targets than standard foreign policy sanctions (17). This has been attributed to factors which range from the stark economic asymmetry between the EU as a donor and ACP countries as recipients to the highly institutionalised nature of the consultation procedure (18). For our purposes, the main question is how the resumption of aid was affected in those cases in which the suspended recipient moved towards compliance. Cases of suspended beneficiaries present the same dilemmas for senders evidenced by countries under foreign policy sanctions: if sanctions are lifted once the target has started to take some steps towards compliance, the incentive to further progress is removed. But if sanctions are left intact until the objectives have been fully attained, targets may be discouraged because they are not reaping the benefits of compliance along the way. It may also reinforce the belief, reportedly shared by some targets, that sanctions will not be lifted even after full compliance has been achieved.

To resolve this dilemma, a method for resumption of assistance was developed in the context of the crisis that erupted in Côte d’Ivoire in late 2000. The presidential and legislative elections, held in late 2000, were characterised by restrictions preventing the opposition from participating freely, as well as by the eruption of violence, resulting in grave human rights violations against civilians (19). Moreover, the electoral crisis unfolded after the current authorities, who had acceded to power following a military coup staged in December 1999, had committed to a timetable for elections and to guaranteeing the separation of consultations launched in February 2001, the Ivorian authorities promised to conduct a full and transparent investigation into the atrocities perpetrated during the military regime, and to open up the political system. Yet, despite satisfactory local elections, the political system had not yet been fully opened up, nor was a judicial investigation into the atrocities launched. In order to ensure that the authorities followed up on their commitments, and in view of the mixed record of compliance by the Ivorian authorities, following the closure of consultations in July 2001, the EU decided to adopt what was labelled the ‘gradual and conditional approach’.

The Council of the EU’s ‘gradual and conditional approach’ is reflected in the letter addressed to the Ivorian President following the conclusion of consultations. Having noted that significant measures had already been taken, although some were still to be implemented, the Council outlined the following process for resumption of assistance and the implementation of new projects:

- Initial disbursements would focus on social issues, the private sector and support to institutions;

- Once new and substantial progress had been made towards fulfilling undertakings, over and above that already achieved, aid would be rolled out progressively;

- Following a further review of the situation establishing that the undertakings had been fulfilled, full cooperation would be resumed (20).

In view of satisfactory progress by the Ivorian government, cooperation was fully resumed six months later (21). The introduction of the ‘gradual and conditional’ approach to aid resumption constituted a major step in facilitating responsiveness to partial implementation of EU demands, creating a blueprint that could be used in crises elsewhere. Through the consultation procedure, targets are offered several institutional ‘antechambers’ before suspension takes place. The emphasis on dialogue and the legal requirement of calling consultations with the ACP country in question – often attended at the highest level - prior to deciding on suspension offers an avenue conducive to negotiation. Once both parties have agreed on a timetable in the consultation phase, the Commission regularly monitors progress according to pre-established benchmarks. Steps by the recipient leadership in the implementation of commitments are rewarded with the progressive resumption of aid.

Merits of a 'gradual and conditional approach'

The benefits of the ‘gradual and conditional approach’ are manifold, and offer useful lessons for the design of sanctions relief initiatives geared towards injecting some dynamism in the dire situations of political stalemate which often result from protracted sanctions episodes. These merits can be identified as three interrelated aspects: firstly, this approach allows the target leadership – and most importantly, its constituency – to reap the economic and political benefits of assistance while sanctions are being rolled back. This is particularly useful for leaderships who need to convince domestic elites about the chosen policy course towards meeting sender demands.

Concurrently, of central importance is that the ‘gradual and conditional approach’ reassures the leadership of the possibility of full resumption of normal relations. A widespread idea among targets is that sanctions do not respond to a concrete objective, but that they follow broader geopolitical motivations unrelated to target behaviour. If the target leadership believes that sanctions will persist until the underlying motives are satisfied, it has little incentive to comply (22). Targeted leaderships often claim that sanctions are about containment, motivated by the desire to halt the target country’s progress (23), or argue that if they complied with sender demands, the goalposts would only shift. Illustratively, former Iranian President Ahmadinejad is reported to have stated: ‘If we give up the nuclear programme, they will ask for human rights. If we give up on human rights, they will ask for animal rights’ (24).

Although this attitude can sometimes be understood as mere rhetorical posturing aimed at rallying the population against adversarial, external powers, certain episodes support the perception that lifting is not always forthcoming after compliance by the target. A number of African states complained that UN sanctions on Libya remained in place after Tripoli had complied with UN Security Council (UNSC) demands on the extradition of the Lockerbie bombing suspects (25). Some members of the UNSC announced that they would veto any weakening of the 1990 sanctions against Iraq as long as President Hussein remained in power, even though the measures had been imposed to compel Iraqi withdrawal from Kuwait and to destroy its weapons of mass destruction (26). Thus, the identification of milestones with measurable indicators, and their public announcement, helps calm anxieties about the lack of sender responsiveness, enhancing the credibility of the promised relief. In addition, it provides the leader with a better case to withstand the incredulity of those sceptical of the goodwill of the sender – sometimes even within the leadership’s own ranks (27).

The EU has traditionally exhibited a propensity to lift sanctions in the face of limited compliance.

The irony about the ‘gradual and conditional’ approach’s ability to disperse the uncertainty surrounding sanctions relief is that the EU has traditionally exhibited a propensity to lift sanctions in the face of limited compliance rather than to leave them in place despite full achievement of the goals (28). For target populations accustomed to the rigidities of sanctions decision-making at the UNSC, or to the severity of the ‘maximum pressure’ campaigns that characterised the US approach in recent years (29), the reassurance provided by a ‘gradual and conditional’ approach is bound to be important.

Transferring the 'gradual and conditional approach' to the CFSP

The sophisticated procedures involved in the decision-making, monitoring and implementation of the ‘gradual and conditional approach’ detailed above, with its facilitating role in the resumption of normal relations, contrasts with their absence from the CFSP framework. The imposition of sanctions under the CFSP does not foresee any antechamber for communication with the target prior to the enactment of the measures. No formal opportunity exists for the agreement of indicators or yardsticks that can be put to task to monitor compliance. Moreover, the goals of sanctions regimes are rarely spelled out. Instead, imposing documents tend to emphasise the actions and norm violations that motivated the imposition of sanctions. This provides very limited information to the target regarding which actions are expected by the stipulations on conditions for lifting or delisting, nor do they guarantee that lifting will follow compliance.

This situation of uncertainty is exacerbated by the introduction of themed or ‘horizontal’ sanctions regimes, such as those addressing the use of chemical weapons or human rights abuses. These sanctions regimes do not admit lifting, but they admit delisting. Because these sanctions regimes are unconnected to political crises in specific territories, a higher degree of uncertainty surrounds the availability of an option for delisting. It is unknown whether the perpetrators of the actions that motivated their listing can take any steps to promote their removal from the list (30). While a coup d’état can be rectified by holding new elections, and an armed conflict can be terminated with a peace agreement, it is difficult to imagine how severe human rights abuses or a chemical attack can be reversed by the perpetrators. This suggests an alternative interpretation, namely, that listings in horizontal sanctions regimes are non-reversible, and that they do not seek to induce any sender, or what needs to be done to promote the lifting of the measures. While it can be presumed that the objectives of sanctions consist in reversing the acts performed, imposing documents neither include any behavioural change in the designees. By contrast, they expect other types of actors to take action: leaderships may be expected to dismiss or sideline designees, or judicial authorities may be expected to indict them. Alternatively, the objective of the lists may be to protect the European population from potential future actions by designees, especially in the case of the anti-terrorism list.

The key challenge is to match milestones with sanctions relief.

Be that as it may, in those cases where compliance towards a pre-established goal is desired, how can the ‘gradual and conditional approach’ be put to task? The application of this notion requires the establishment of a plan for the gradual easing of sanctions in which individual milestones towards compliance reached by the target are reciprocated with the lifting, or substantial easing, of specific sanctions measures. Such a plan ought to be the equivalent to art.96’s ‘roadmap’. The key challenge for the drafters of the plan is to match milestones and sanctions relief in such a way that the target feels the benefits while remaining incentivised to progress towards compliance. As posited by sanctions scholars, policymakers need to determine in advance how much they are willing to relax sanctions in exchange for specific concessions from the target: ‘while too many concessions at the outset can remove the incentive for targets to modify their future behaviour, failing to relax sufficiently can prevent further progress’ (31). For its part, the sender must be reassured that, in the event of reversals, sanctions can be easily reinstated. In the case of a composite entity like the EU, this can be accomplished by suspending rather than lifting the sanctions. In addition, the plan should foresee a mechanism that allows for the reinstatement of the suspended measure in the event of backsliding. A final consideration is that, in order to maximise their chances of success, plans for sanctions relief should ideally involve a dialogue with target authorities, even if this falls short of a full negotiation.

This facilitates some level of commitment by the target, and affords an opportunity to accommodate its concerns to some degree. From that vantage point, target involvement can have a ‘confidence-building’ dimension. One of the best examples of phased suspension of sanctions to date is enshrined in the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) – an agreement that took a remarkable amount of time and effort to negotiate, and that has been hailed as ‘the most comprehensive arms control agreement that exists’ (32). While its implementation proved problematic, it was not a flawed design that derailed the process. By contrast, an attempt at sanctions relief, notably entailing the temporary suspension of bans, offered one-sidedly by the EU to Belarus in 2009, failed to bring about the desired improvement (33).

Lessons from Cotonou

The application of gradual sanctions relief is actually more apt for the CFSP realm than for the EU-ACP context, given that the CFSP employs targeted sanctions. The Cotonou framework only imposed one type of measure, namely, the suspension of development assistance, which could be wielded against state authorities (34). By contrast, the CFSP sanctions toolbox is more diverse, and admits various combinations of measures to provide sanctions relief: selective delisting can be applied when individuals or entities have been designated. Although apparently symbolic, the selective listing and delisting of politicians has proved influential in supporting mediation processes (35). Sectoral restrictions can be adjusted, suspended or terminated. Moreover, targeted sanctions can be suspended for some, but not all, parties to a conflict, or in respect of specific territories. Unlike aid sanctions, they can be applied to or suspended from state authorities and non-state actors alike. The task ahead is to make creative use of the many combinations available, tailoring them to the specificities of the target situation.

To some extent, phased suspensions are already standard practice in EU sanctions regimes. The phasing-out of sanctions regimes like that against Uzbekistan in 2007 or Myanmar in 2013 required two to three years to be completed. In addition, some sanctions regimes are never fully lifted: the lifting of the sanctions on Myanmar never included the arms embargo, which remained in place until a new sanctions regime was enacted in 2018. The same was true for the Belarus sanctions regime, which persisted in a minimal form from its suspension in 2016 until it was revived following the electoral violence of summer 2023. The EU's arms embargo on China is the only enduring measure from a package of sanctions imposed in response to the Tiananmen crackdown in 1989, most of which vanished quickly. Currently, a moribund sanctions regime on Zimbabwe persists with just one entity listed, Zimbabwe Defence Industries (Pvt) Ltd, merely accompanied by an arms embargo (36). Similarly, in the Burundi sanctions regime only one designee, the national Intelligence officer Mathias-Joseph Niyonzima, remains on the list (37). From this perspective, once the sanctions have been considerably relaxed, they may stall for some time at the penultimate stage. This underlines, once again, how sanctions may help mitigate crises, but are ultimately unable to resolve underlying problems that cause recurrent instability in the targets.

Conclusion

This Brief has highlighted an aspect traditionally overlooked in the debates about sanctions’ effectiveness: the potential deployment of sanctions relief as an incentive to elicit compliance towards sanctions goals. Noting that the CFSP currently lacks any provisions for mitigation or lifting, it identifies several obstacles that stand in the way of realising the untapped benefits of sanctions relief: a traditional mindset that focuses on the coercive impact of sanctions, rather than the potential of relaxation, and the indeterminacy of sanctions goals that characterises the CFSP. It identifies a blueprint for sanctions relief: the resumption of development assistance to suspended beneficiaries in the context of the ACP-EU Partnership Agreement, in whose framework a ‘gradual and conditional approach’ has evolved. This approach can be usefully transferred to the CFSP framework, where it offers considerable potential thanks to the flexibility of targeted measures.

References

1. Meissner, K. and Graziani, C., ‘The transformation and design of EU restrictive measures against Russia’, Journal of European Integration, Vol. 45, No 3, 2023, pp. 377-394.

2. See EU sanctions map at: https://sanctionsmap.eu/#/main.

3. Felbermayr, G., Kirilakha, A., Syropoulos, C., Yalcin, E. and Yotov, Y., ‘The global sanctions data base’, European Economic Review, No 129, 2020 (http://www.globalsanctionsdatabase.com/).

4. Portela, C., ‘Sanctions, conflict and democratic backsliding: A user’s manual’, Brief No 6, EUISS, May 2022.

5. Biersteker, T., Eckert, S. and Tourinho, M., Targeted Sanctions: Theceffectiveness of UN action, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2016.

6. Hudakova, Z., Biersteker, T. and Moret, E., Sanctions Relaxation and Conflict Resolution: Lessons from past sanctions regimes, The Carter Centre, Atlanta, 2021.

7. Swedlund, H., ‘Can foreign aid donors credibly threaten to suspend aid? Evidence from a cross-national survey of donor officials’, Review of International Political Economy, Vol. 24, No 3, 2017, pp. 454-496.

8. Pellet, A. and Miron, A., ‘Sanctions’, in Wolfrum, R. (ed.), Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, 2013, vol. IX. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 1-15.

9. Zimelis, A., ‘Conditionality and the EU-ACP Partnership: A misguided approach to development?’, Australian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 46, No 3, 2011, pp. 389-406.

10. Borzyskowski, I. and Portela, C., ‘Sanctions cooperation and regional organisations’, in Aris, S., Snetkov, A. and Wenger, A. (eds.), Inter- organisational relations in international security: Cooperation and competition, 2018, Routledge, pp. 240-61.

11. See European Council, ‘Post-Cotonou Agreement’ (https://www. consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/cotonou-agreement/).

12. The Cotonou Agreement has been replaced by the Post-Cotonou Agreement, whose signature and provisional application was greenlighted by the Council in July 2023.

13. Partnership agreement between the members of the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States of the one part, and the European Community and its Member States, of the other part, signed in Cotonou on 23 June 2000, OJ L 317, 15 December 2000, p. 3–353, art. 96 (https://eur-lex. europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:22000A1215(01)&from=EN).

14. Ibid, art. 96.

15. Ibid.

16. See European Council, ‘Post-Cotonou Agreement’, op.cit.

17. Hazelzet, H., ‘Suspension of development cooperation: An instrument to promote human rights and democracy?’, European Centre for Development Policy Management, Discussion Paper 64B, Maastricht, 2005.

18. Portela, C., European Union Sanctions and Foreign Policy: When and why do they work?, Routledge, Abingdon, 2010.

19. Laakso, L., Kivimäki, T. and Seppänen, M., Evaluation of coordination and coherence in the application of Article 96 of the Cotonou Partnership Agreement, Aksant, Amsterdam, 2007.

20. Council of the EU, Letter concluding consultations with Côte d’Ivoire under Art. 96 of the ACP-EU Partnership Agreement (2001/510/EC), 25 June 2001.

21. Following the intensification of fighting in the north of the country, and in view of the threat of civil war, the crisis was handled by the UN Security Council, which imposed a mandatory sanctions regime via Resolutions 1572 (2004) and 1643 (2005).

22. Jones, L. and Portela, C., ‘Evaluating the success of international sanctions: A new research agenda’, Afers Internacionals, No. 125, pp. 39- 60.

23. Kluge, J., ‘Taking stock of US sanctions on Russia’, Foreign Policy Research Institute, Philadelphia, 14 January 2019 (https://www.fpri.org/ article/2019/01/taking-stock-of-u-s-sanctions-on-russia/).

24. Quoted in ‘Interview with Political Islam expert Vali Nasr: Removing Saddam strengthened Iran’, Al Jazeera, 5 September 2006.

25. Organisation of African Unity, ‘A Crise entre a Grande Jamahiriya Árabe Líbia Popular Socialista e os Estados Unidos da América e o Reino Unido’ [‘The crisis between the Great Socialist People’s Libyan Arab Jamahiriya and the United States of America and the United Kingdom’], AHG/Dec. 127 (XXXIV), 1998 (https://archives.au.int/bitstream/ handle/123456789/1337/AHG%20Dec%20127%20XXXIV_P%20.pdf).

26. Chesterman, S. and Pouligny, B., ‘Are sanctions meant to work? The politics of creating and implementing sanctions through the United Nations’, Global Governance, Vol. 9, No 4, 2003, pp. 503-18, p. 509.

27. Portela, C. and Van Laer, T., ‘The design and impact of individual sanctions: Evidence from elites in Côte d’Ivoire and Zimbabwe’, Politics and Governance, Vol. 10, No 1, 2022, pp. 26–35.

28. European Union Sanctions and Foreign Policy, op.cit.

29. Elliott, K., ‘US approaches to multilateral sanctions: Co-operation and coercion intertwined’, in Charron, A. and Portela, C. (eds.), Multilateral Sanctions Revisited: Lessons learned from Margaret Doxey, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal, 2022, pp.34-50.

30. Portela, C., ‘Horizontal sanctions regimes: Targeted sanctions reconfigured?’, in Beaucillon, C. (ed.), Research Handbook on Unilateral and Extraterritorial Sanctions, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, 2021, pp.441-457.

31. Sanctions Relaxation and Conflict Resolution, op.cit., p.37.

32. Gärtner, H., ‘The fate of the JCPOA’, in Gärtner, H. and Shahmoradi, M. (eds.), Iran in the International System, Routledge, Abingdon, 2019.

33. Portela, C., ‘Belarus and the European Union: Sanctions and partnership?’, Comparative European Politics, Vol. 9, No 4, 2011, pp. 486–505.

34. Portela, C., ‘Are EU sanctions “targeted”?’, Cambridge Review of International Affairs, Vol. 29, No 3, 2016, pp. 912-29.

35. Portela, C. and Romanet-Perroux, J.L., ‘Mediation and sanctions in Libya: Synergy or obstruction?’, Global Governance, Vol. 28, No 2, 2022.

36. Council Decision (CFSP) 2022/227 of 17 February 2022 amending Decision 2011/101/CFSP concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Zimbabwe, OJ L 38, 18.2.2022, p. 5–7 (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal- content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32022D0227).

37. Council Decision (CFSP) 2022/2051 of 24 October 2022 amending Decision (CFSP) 2015/1763 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Burundi, OJ L 275, 25.10.2022, p. 72–73 (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/ legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32022D2051).