You are here

African conflictivity

Introduction

Today’s world is characterised by deep interdependencies and a growing degree of connectivity, namely the ability to bring people, goods, systems and societies closer together, while fostering deeper economic relations and people-to-people ties. For Africa, this focus on connectivity is more important than ever, as it is a critical factor underpinning the continent’s aspirations. This is clearly laid out in the African Union’s Agenda 2063 (1), which has identified the need to speed up actions on African connectivity as key to supporting accelerated integration, growth, and development. In 2012, the African Union (AU), in partnership with the African Development Bank (AfDB) and the African Union Development Agency (AUDA-NEPAD), set out the Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA) (2), an ambitious agenda to connect and integrate the African continent (3). The development of transport infrastructure is particularly important for African countries to reap the benefits of the recently adopted African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). Furthermore, many global actors, such as the European Union (EU) with its Global Gateway, or China with its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), have attached increasing importance to connectivity in Africa, financing infrastructure projects and exploring business opportunities that could arise in this field.

At the same time, infrastructure connectivity is not just an asset used to promote African development and trade, but also an element that interacts with the surrounding socioeconomic, political and institutional environment. Far from being an abstract issue, infrastructure connectivity is a vector of transformation that can trigger socioeconomic and political changes in conjunction with other societal processes (4).This transformative power is extremely relevant in fragile and conflict-affected (FCA) areas on the African continent, as connectivity, in its interaction with underlying conflict and societal factors, has the potential to contribute to either advancing or hindering peacebuilding and stabilisation efforts. In this Brief, the term ‘conflictivity’ (5) is used to refer to the latter scenario, i.e., when connectivity becomes an accelerator of fragmentation and fragility, exacerbating grievances and fuelling conflict dynamics. It is extremely important to explore how conflicts and connectivity interact to make sure that the ‘connectivity momentum’ that Africa has experienced does not lead to this conflictivity scenario, but rather provides an opportunity to reduce violence and address persisting social and institutional fragilities. Assessing African connectivity through a conflict-sensitive lens is therefore key to the establishment of lasting peace and the achievement of the continent’s long-term development goals.

Against this backdrop, this Brief aims to unpack the linkage between connectivity and conflict dynamics in Africa. Rather than dealing with connectivity in a broad sense, the Brief focuses specifically on transport infrastructure connectivity, due to the importance that this particular type of connectivity has for the economic future of the African continent, its unfolding economic integration and its potential to enhance the governance of countries. First, the Brief analyses the role that transport infrastructure connectivity can play in building peace and reducing violence and fragility in Africa; second, it examines how infrastructure projects can pave the way towards the emergence of conflictivity situations; third, it analyses the vision that the EU proposes with regard to African connectivity; finally, it provides strategic-level considerations to assess the implications of connectivity from a conflict-sensitive perspective, thus augmenting the ability to avoid conflictivity, while realising economic and social benefits.

Connecting Africa to build peace

The growing focus on transport connectivity is a huge opportunity to build a new model of connectivity across Africa, capable of advancing trade, economic development and peace. Transport systems can contribute to the stabilisation and reconstruction of FCA areas in Africa through different channels. One key component is the use of physical assets as instruments for the central state to employ its ‘infrastructure power’, namely ‘the capacity to penetrate its territories, logistically implement political decisions’ (6), and establish a visible presence of the state, advancing social cohesion and enhancing the legitimacy of the central authority across the country. In other words, transportation networks in Africa can be seen as a proxy for state capacity (7). Furthermore, re-establishing movement along key transport links and corridors facilitates the deployment of security forces and access to state services such as administration and justice, thus enhancing the delivery of humanitarian support and mitigating the climate of economic hardship in which armed groups flourish (8).

Transportation networks in Africa can be seen as a proxy for state capacity.

Transport connectivity projects can also defuse fragility dynamics by creating employment opportunities and improving the economic and business environment. This mechanism comes into play mainly when connectivity projects are specifically designed to involve local communities, especially women, and spread benefits across local populations (9). Employment generation increases the opportunity cost of resorting to violence while providing a way out of poverty for vulnerable people, thus contributing to reducing the risk of radicalisation. For instance, a survey conducted in Liberia revealed that those who obtained employment through road construction projects were better able to take care of themselves and their families (10). At the same time, employment creation could be particularly useful to create enduring conditions for political and social reconciliation, by targeting young men and groups with a higher predisposition towards violence (11). In this regard, the integration of such projects into disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) programmes offers a promising way forward, as it would provide former fighters with an incentive for maintaining peace, while preventing young people from resorting to violence, as for instance happened in the Central African Republic (12) or the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) (13).

Data: AfDB, Africa Infrastructure Development Index, 2022

Another channel through which infrastructure projects contribute to peacebuilding and development efforts is by connecting populations in conflict-prone areas. Enhancing rural transportation networks and services to open up remote areas and increase access to urban centres and markets is instrumental in promoting social cohesion and economic inclusion of vulnerable populations, while fostering community ownership. Connectivity thus has the potential to overcome the high level of spatial segregation and fragmentation inherited from European colonisers, whose biased model of transport connectivity was usually limited to the connections necessary for the export of minerals or agricultural products, contributing to the African continent’s conflict proclivity (14). Indeed, despite recent efforts, the transport network in Africa remains poor on average. When it comes to the ratio of paved roads to total roads, sub-Saharan Africa is the weakest-performing region (15). The most concerning element is that in many countries road density has effectively declined over the last few years, as shown in the graph opposite.

The link between transport infrastructure building and peacebuilding is clearly laid out, for instance, in the National Recovery and Peacebuilding Plan 2017-21 of the Central African Republic (16). The strategy emphasises the need to improve road infrastructures across the country, especially in rural areas, as a tool to reduce the widening gap between the elite and the rest of the population and reach neglected communities, whose isolation has fuelled armed confrontation and violence in the country. Another interesting example is the DRC, ranked the sixth most fragile country in the 2022 Fragile States Index (17). The country’s critical situation is compounded by poor connectivity, which has increased geographic isolation, exacerbating social and economic inequalities across and within provinces and laying the foundations for the proliferation of armed groups. As recognised by the World Bank (18), an important element on which peacebuilding and stability strategies could capitalise would consist in improving road connectivity in the DRC, to integrate border populations, support cross-border trade activities, improve access to services and overcome exclusionary dynamics.

The focus on African transport connectivity is expected to increase as a result of the growing economic and trade integration underpinned by the AfCFTA (19). This trade-driven attention to connectivity projects has the potential to generate positive externalities. Stronger economic, social and infrastructure connections would have the added advantage of reducing the risk of cross-border conflicts by increasing the economic interdependence of the member countries, which would raise the costs of conflict (20). In conflict-prone situations, access to markets is necessary to restore economic growth and generate the preconditions for peace and reconstruction, which explains why the rehabilitation of damaged transport infrastructure has emerged as a priority among donors and governments (21).

The Great Lakes provides an interesting example of a region where small-scale cross-border trade is strongly associated with a reduction in conflict and gender-related violence: indeed, many of those who participate in cross-border trade in the Great Lakes are women and young people (22), thus making it more likely that the benefits are directly invested in the household, thereby further reducing vulnerability to shocks and the risk of youth radicalisation.

The dark side of the story: African conflictivity

Yet all that glitters is not gold. If poorly implemented, connectivity may not only fail to foster stabilisation and reduce violence but may even turn out to be a driver of grievances and exclusion, amplifying conflicts and tensions and laying the foundations for the onset of new patterns of fragility. This corresponds to what might be termed a ‘conflictivity scenario’, i.e. a situation whereby transport connectivity can fuel conflict and fragility dynamics, rather than becoming a stabilising factor. While infrastructure projects are not per se the cause of conflict escalation, under this conflictivity scenario, connectivity contributes to the widening of existing faultlines, creating or deepening cleavages across the geographical, functional and social spaces, and exacerbating the burden of colonial legacies. So, what are the factors contributing to this conflictivity scenario? Conflictivity may arise when the delivery of physical assets in FCA areas is done in an institutional void, without a broader stabilisation strategy or without being adequately coordinated with local authorities and populations. In addition to these endogenous characteristics, the rise of conflictivity needs to be assessed in combination with two trends which can accelerate its emergence, namely multipolar competition and urbanisation.

Access to state services in Africa reduces the risk of conflict, at the same time as groups’ internal connectedness increases this potential.

Building roads is not just a tool for states to access local populations but can equally be a means through which armed groups gain the infrastructure for mobilisation. Focusing on opportunities for rebellion among African ethnic groups and building on road network data, it has been shown (23) that access to state services in Africa reduces the risk of conflict, at the same time as groups’ internal connectedness increases this potential. This strictly depends on the strength of the ‘infrastructure power’ that African are properly supervised and managed, new infrastructure projects can become a source of funds for insurgents and militias. Armed checkpoints along key trade routes represent core financing activity for many armed groups in Africa. In North and South Kivu in the DRC, for instance, between 2016 and 2019, more than 800 roadblocks were identified, about one every 10 miles, with people most often charged for passing through roadblocks, in addition to being charged for accessing natural resources or markets (24).

At the same time, conflictivity is not just about intrastate conflicts, but also includes the risk that road projects become embedded in cross-border interstate conflict dynamics, contributing to the internationalisation of instability hotspots. A case in point is the massive road project launched by Uganda at the end of 2021 (25) to open trade routes to three cities in eastern DRC. This project was launched amid growing tensions between Rwanda and Uganda, which accuse each other of backing militias operating in eastern DRC. In particular, the situation escalated after the decision by the DRC to allow Uganda to deploy troops to fight rebels based in eastern DRC. In this context, the road project is seen by Rwanda as a provocative and unfriendly act, as it includes plans for the construction of roads near the Rwandan border, jeopardising Kigali’s interests in the area. In particular, the memorandum of understanding (MoU) on road construction is allegedly part of the military agreement which allowed Uganda to deploy troops in the DRC (26), highlighting the close connection between infrastructure objectives and political and military goals.

Data: European Commission, 2022

Without overarching infrastructure strategies, transport projects can increase the chance of the transport system becoming a conduit for intensified predation and a channel for the spread of illegal economic activities. When police, customs, enforcement agencies and other key stakeholders are not equipped with adequate technical tools and financial resources, those connectivity projects meant to promote legitimate economic growth might risk leading to the opposite, states can employ. Moreover, unless infrastructures by facilitating illicit markets and exports. Weak governance and unchecked cross-country rivalries risk derailing infrastructure projects which could otherwise have the potential to generate significant benefits, as has been happening with the Ugandan road-building plan in the DRC. Another example is South Africa, a country with a huge potential for economic integration due to its key position in terms of maritime trade, where the high rate of violent crime against freight trucks and vans poses a major risk to road freight transport (27). Furthermore, without strong institutions, it is difficult to ensure proper supervision and monitoring of the projects, identify lessons learned from project-related activities, assess the impact on local populations and create enduring and shared benefits.

Moreover, the choice of involving either local or central stakeholders, and to what extent, is likely to affect the way transport connectivity impacts on FCA areas. Indeed, transport projects can have a much more positive effect on conflict dynamics when they are community-driven, that is, when local communities are involved in identifying their own specific needs and devising appropriate solutions. Investing in large-scale transport projects in fragile contexts carries the risk of not addressing deep-rooted grievances and bypassing or perpetuating the inequalities which are at the core of the conflict (28). For instance, it has been shown that mega-infrastructure projects across East Africa have a high potential to significantly aggravate existing fragilities through different channels, including the risk that uncontrolled inward migration generates significant animosity and foments strong political opposition within project-affected communities (29). While acknowledging that large-scale projects are crucial to upholding trade and economic development in Africa, it is important to launch pilot projects to explore concrete ways to apply conflict-sensitive and community-driven approaches to connectivity initiatives, bearing in mind that each context has its own specificities which require tailored responses.

The underlying dynamics that might lead to the emergence of a conflictivity scenario risk being amplified by the new geopolitical centrality that the African continent has gained on the international stage. A growing number of global powers have intensified their engagement with African countries, creating new patterns of multipolar competition, among which connectivity plays a key role. Competing external actors – such as China, India, Japan or the United Arab Emirates – have been looking at infrastructure connectivity as a tool to project or enhance their influence on the continent and balance the rise of rival countries, largely preferring large-scale infrastructure to community-driven projects. This is confirmed by the importance attached to port infrastructure development, especially in Eastern Africa, as it provides access to main maritime routes and chokepoints (30). A case in point is the BRI launched by China, which is inherently a geopolitical tool, masterminded by Beijing to advance its strategic interests. While investments in megaprojects could be an opportunity to boost intra-African and international trade, this model of connectivity risks exacerbating grievances and resulting in the exclusion of local populations from shared benefits, which are indeed among the core factors triggering the number of protests and tensions that have flared up in response to large-scale Chinese-financed projects, fuelled by the perception that China’s economic influence is harmful to national interests (31).

Lastly, the rise of the conflictivity scenario risks being accelerated by the unmanaged unfolding urbanisation process, which is radically shaping African economies and societies (32). Africa’s rapid urbanisation is coupled with low levels of investment in infrastructure, which prevent African cities from delivering agglomeration economies and reaping urban productivity benefits (33). If the growing population in African cities is not matched with appropriate transport infrastructures to address the needs of urban and peri-urban communities, urbanisation could become another element contributing to the materialisation of conflictivity situations. In other words, due to the lack of urban planning and low levels of investment in infrastructure, African cities are not only the physical arena where political mobilisation takes place, but have become themselves a driver of grievances, which produces and reproduces contestation patterns over low job opportunities and lack of access to urban services, among other things (34). This highlights the importance of investigating the link between African connectivity and fragility through the lens of urban governance.

African connectivity: What vision for the EU?

It is thus clear that spatial variations triggered by higher or lower transport connectivity can affect conflict dynamics in Africa, paving the way either for a scenario where fragility is addressed and conflict risks mitigated, or for a scenario where conflictivity prevails. In both cases, given its transformative power, the conceptualisation of conflictivity needs to be fully integrated into the strategic approach shaping policy towards Africa. When it comes to the EU, a seesaw approach has been adopted towards connectivity in Africa, moving from a ‘securitarian’ perspective aimed at hindering human mobility-centred connectivity, to a ‘geopolitical’ paradigm under which connectivity has been seen strictly in relation to the opportunity to partner with African countries to develop transport infrastructures.

In the absence of a holistic approach to connectivity, the conflictivity scenario will unavoidably prevail

If we go back to the last 4-5 years of the past decade, when the political and strategic debate was dominated by migration and related security/humanitarian concerns (35), connectivity in Africa was largely conceived by Europeans as synonymous with human mobility. This resulted in an increased effort to constrain connectivity, in an attempt to curb migrant flows and prevent the spread of terrorism. This approach has led to the conceptualisation of African borders as solid, fixed dividing lines, which need to be preserved through rigid border management policies and ad hoc military missions. A case in point is the Sahelian region, where the EU approach has been largely characterised by a migration-driven emphasis on hardened border control, not properly balanced by support to local populations, who depend on migration for their livelihoods (36).

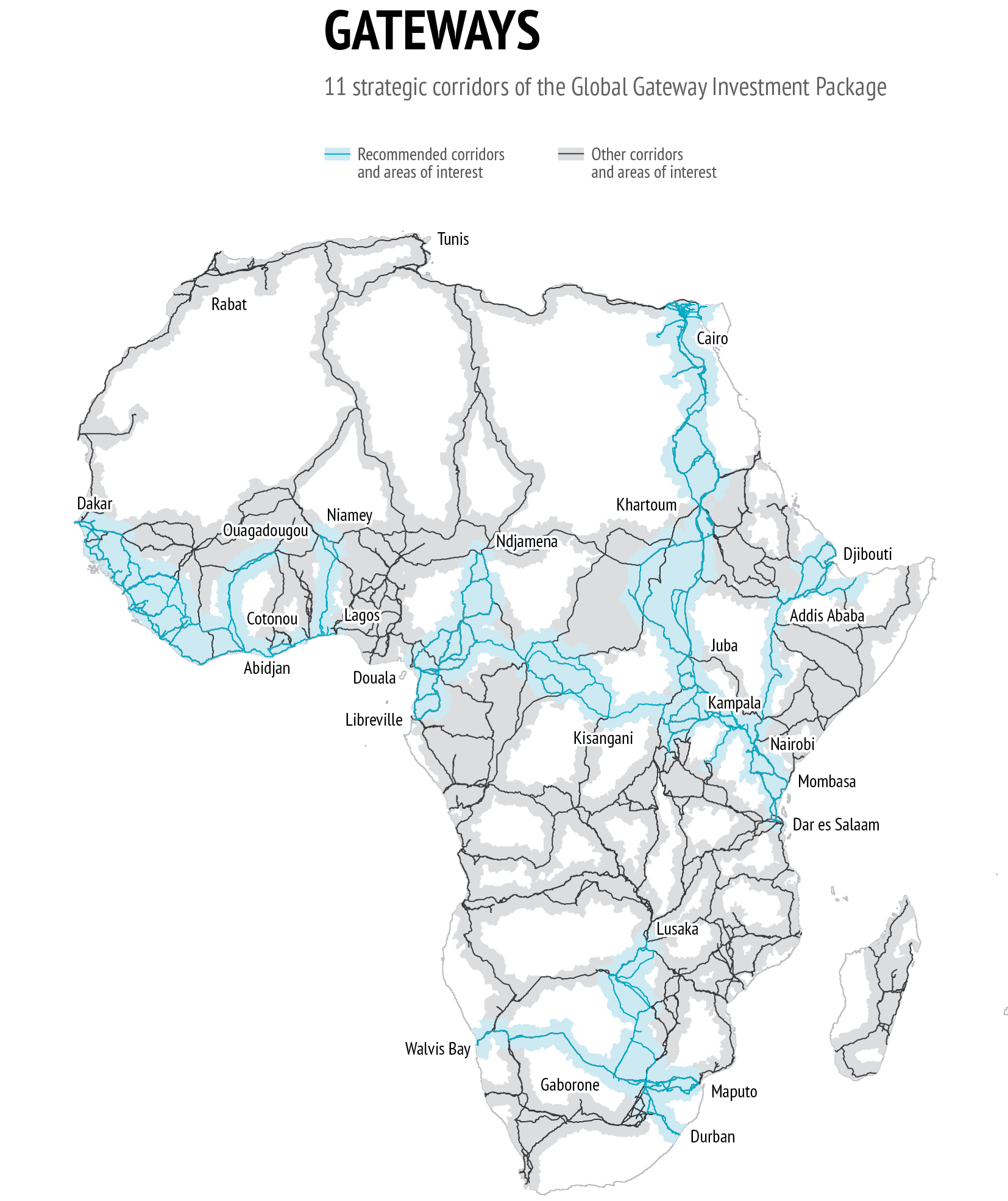

The EU has progressively nuanced this securitarian approach and started looking at African connectivity through fresh lenses, as the new narrative describing Africa as a ‘land of opportunities’ has emerged in the international community (37). This emerging vision is linked to the opportunities arising from the AfCFTA and the need to enhance strategic partnership to support bilateral trade and investment, especially given the growing multipolar competition. In this regard, providing support to African countries to improve connectivity and transport infrastructure development is a key pillar of the renewed EU strategic posture laid out in the 2020 joint communication ‘Towards a comprehensive strategy with Africa’ (38). In light of this approach, as part of the €150 billion Global Gateway Africa–Europe investment package, the EU intends to support the African continent by financing quality connectivity infrastructure through multi-country Team Europe initiatives. It is within the context of this aim that 11 strategic corridors have been identified as key in order to facilitate intra-African and Africa–Europe trade, improve connectivity between both continents, develop value chains in Africa and support territorial development, embracing both rural and urban contexts (39).

The African connectivity model envisioned under the Global Gateway also has a geopolitical dimension, with a major focus on large-scale projects, to rival global players and re-establish the EU’s standing. The first and most direct target of this approach is China, which, as illustrated above, has been able to promote an interest-oriented connectivity model. While it is legitimate for the EU and other global powers to use connectivity to advance their geopolitical agenda, this needs to be balanced out by other key considerations: as argued above, if connectivity is pursued just as a geopolitical tool without factoring in its impact on conflict dynamics, societies and institutions, it risks becoming a driver of grievances and an accelerator of geographic and socioeconomic fragmentation. In the absence of a holistic approach to connectivity, the conflictivity scenario will unavoidably prevail, jeopardising stabilisation efforts on the continent.

The Global Gateway seeks to overcome the flaws which might stem from poorly conceptualised connectivity by adopting a quantitative methodology to assess the strategic corridors to be implemented. The 11 corridors have been identified analysing potential trade-offs across four scenarios, focusing on 32 indicators related to economic welfare, equity, social inclusion, impact on the environment and impact on vulnerable groups (40). One of these scenarios, the ‘human development, and peace and security’ scenario, highlights that these corridors can function efficiently and effectively only in a context of peace and security, representing key conditions for sustainable development. This methodology represents an innovative approach which can be replicated, and it would be important to further scale up this conflict-sensitive approach in the assessment of connectivity projects, recognising connectivity as a constitutive element of conflict dynamics and at the same time leveraging its potential to address fragility. This could result in stronger cooperation with other institutions, such as the World Bank, the United Nations or the AfDB, and with local organisations and communities, to find concrete entry points for joint-financed infrastructure projects.

The way forward: Designing a connected and peaceful Africa

Overall, it is crucial to recognise that connectivity can have both beneficial and detrimental impacts on African conflicts and should therefore be implemented with caution. A clear articulation of connectivity projects in accordance with stabilisation priorities and objectives needs to be fully explored when it comes to supporting decision-makers. Against this backdrop, some strategic considerations can be elaborated to create the conditions for connectivity to successfully contribute to reducing violence and fragility in Africa and prevent the conflictivity scenario from arising.

Connectivity is not just black and white. The dichotomised representation of connectivity as either ‘good’ or ‘bad’ does not help fully harness the potential and mitigate the risks of connectivity in Africa, as it fails to grasp the multiple, diverse and complex links between transport systems and the surrounding socioeconomic environment, especially in FCA areas. It is therefore crucial to avoid fixed paradigms and frame connectivity projects within the region- and/or country-specific context. In the case of the Sahel, for instance, connectivity underpinning the mobility of people and goods, which is an inherent characteristic of the region, should be part of the solution rather than being addressed only as a challenge.

Connectivity is more than just geopolitics. Looking at African connectivity only through the lens of geopolitical competition could be counterproductive, leading to a preference for large-scale projects and producing negative results in terms of exacerbated violence in FCA areas. While large-scale projects revolving around strategic corridors are crucial for trade integration and economic development, a more comprehensive and multifaceted approach would be needed. It would be beneficial to pilot cross-country transport projects to explore concrete ways to apply community-driven and conflict-sensitive approaches to large-scale infrastructures, for instance along key corridors or in landlocked states to facilitate access to the main ports. This would produce a more direct positive impact on local populations, fostering community-building and improving collective ownership of the infrastructures.

Connectivity is also about conflict and peace. Conflict dynamics need to be considered early in the process of transport project design, where the impact of connectivity on conflict and fragility, both positive and negative, can be analysed and operationalised in detail across all the phases of the project. It is therefore imperative to adopt a conflict-sensitive approach by putting together transport infrastructure development, policy, and conflict-management experts. Although undertaking a project in a context of insecurity and conflict can be extremely challenging, the risks of ‘doing nothing’ are higher because the current instability and insecurity are likely to intensify further without connectivity and development. In this regard, it is important to introduce flexibility in the design of projects to make them adaptable to the risky and volatile environment where they operate.

Connectivity needs people. The effects on peace of transport assets can emerge only in interaction with what people actually use such assets for. Therefore, in order to make connectivity a catalyst of stability capable of delivering long-lasting results, it is crucial to adopt a bottom-up approach, address the needs of vulnerable groups and bring together all key actors that have a stake in making and keeping infrastructures safe, including local communities and authorities. Furthermore, it is essential to design connectivity projects to create employment opportunities for local populations, especially women and demobilised soldiers, making sure that the benefits of infrastructures are spread across groups in an inclusive way.

Connectivity alone does not work. Infrastructure investments may be of little relevance, or even counterproductive if they are not part of a broader multidimensional stabilisation strategy focusing on the underlying causes of conflict and fragility. Therefore, enhanced connectivity needs to be integrated into a broader stabilisation strategy, including institutional strengthening and capacity-building activities focused on the planning, implementing, and leveraging of infrastructure projects.

In conclusion, connectivity can be part of the solution for Africa to go beyond the barriers created by geography and history, fostering cross-border relations and helping countries address the grievances which fuel fragility and radicalisation. Nevertheless, connectivity is not per se a catalyst for peace and a mitigator of risks in FCA areas. Instead, its impact largely depends on the external socioeconomic and institutional context. Accounting for the connectivity– conflict nexus is key to propose a fresh model of transport connectivity capable of supporting African countries in this ‘connectivity momentum’ and thus avoid the emergence of the conflictivity scenario.

References

1. African Union, ‘Agenda 2063. The Africa we want’, September 2015 (https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/36204-doc-agenda2063_ popular_version_en.pdf)

2. African Union and African Development Bank, ‘PIDA-PAP 2 Financing Strategy’, Final Report, April 2021 (https://www.au-pida.org/download/ pida-pap2-financing-strategy/).

3. Transport connectivity is one of the four pillars of PIDA. The others are: water, energy and ICT. PIDA is currently under the second phase of implementation, with the final list of projects adopted in 2021 with a 2030 vision.

4. Schouten, P. and Bachmann, J., ‘Roads to peace? The future of infrastructure in fragile and conflict-affected states’, Danish Institute for International Studies and United Nations Office for Project Services, 2017.

5. The term ‘conflictivity’ is the outcome of a fruitful discussion that the author had with Dr Giovanni Faleg of the EUISS. The author would like to thank him for his feedback and support.

6. Mann, M., ‘The autonomous power of the state: Its origins, mechanisms and results’, European Journal of Sociology, Vol. 25, No 2, 1984, pp. 185–213.

7. Müller-Crepon, C., Hunziker, P. and Cederman, L. E., ‘Roads to rule, roads to rebel: Relational state capacity and conflict in Africa’, Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 65, 2021, pp. 563–590.

8. Bachmann, J. and Schouten, P., ‘Concrete approaches to peace: Infrastructure as peacebuilding’, International Affairs, Vol. 94, No 2, 2018, pp 381–398.

9. Ibid.

10. Rebosio, M. and Wam, P., Violent Conflict and the Road Sector: Points of interaction, World Bank, Washington, 2011.

11. Collier, P., ‘Post-conflict recovery: How should strategies be distinctive?’,Journal of African Economies, Vol. 18, 2009, pp. i99–i131.

12. MINUSCA, ‘Activities – Disarmament demobilization reintegration’ (https://minusca.unmissions.org/en/DDR_En).

13. United Kingdom Department for International Development, Supporting infrastructure development in fragile and conflict-affected states: Learning from experience, 2012 (https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57ebe67de5274a0eba000011/FCAS_infrastructure_final_report_0.pdf).

14. Potts, J. C., Cleaver-Bartholomew, A. and Hughes, I., ‘Comparing the roots of conflict in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa’, Inquiries Journal, Vol. 8, No 4, 2016.

15. Calderón, C., Cantú, C. and Chuhan-Pole, P., ‘Infrastructure development in sub-Saharan Africa’, Policy Research Working Paper, No 8425, World Bank, 2018 (https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/ handle/10986/29770/Infrastructure-development-in-Sub-Saharan- Africa-a-scorecard.pdf?sequence=5).

16. World Bank, Central African Republic: National recovery and peacebuilding plan 2017–21, World Bank Group, 2017, (https:// documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/817461516999933538/central-african-republic-national- recovery-and-peacebuilding-plan-2017-21).

17. See: https://fragilestatesindex.org/country-data/.

18. World Bank, FY22-26 country partnership framework for the Democratic Republic of Congo, World Bank Group, January 2022 (https://documents1. worldbank.org/curated/en/214221646062568502/pdf/Congo-Democratic- Republic-of-Country-Partnership-Framework-for-the-Period-FY22-26. pdf).

19. United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, The African Continental Free Trade Area and demand for transport infrastructure and services, 2022 (https://repository.uneca.org/handle/10855/47596).

20. Martin, P., Mayer, T. and Thoenig, M., ‘Civil wars and international trade’, Journal of the European Economic Association, Vol. 6, 2022, pp. 541– 50, 2022.

21. Rubaba, A., Barra, A. F., Berg, C. N., Damania, R., Nash, J. D. and Russ, J., ‘Infrastructure in conflict-prone and fragile environments: Evidence from the Democratic Republic of Congo’, Policy Research Working Paper, No 7273, World Bank, 2015.

22. World Bank, Great Lakes trade facilitation and integration project (P174814), Project Information Document, 2020.

23. ‘Roads to rule, roads to rebel: Relational state capacity and conflict in Africa’, op. cit.

24. Schouten, P., Roadblock Politics – The origins of violence in Central Africa, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2022.

25. Reuters, ‘Uganda launches road-building in Congo to boost trade’, 5 December 2021 (https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/uganda- launches-road-building-congo-boost-trade-2021-12-05/).

26. Africa Center for Strategic Studies, ‘Rwanda and the DRC at risk of war as new M23 rebellion emerges: An explainer’, 2022.

27. Mlepo, A. T., ‘Attacks on road-freight transporters: A threat to trade participation for landlocked countries in Southern Africa’, Journal of Transportation Security, Vol. 15, 2022, pp. 23–40.

28. ‘Roads to peace? The future of infrastructure in fragile and conflict- affected states’, op. cit.

29. Unruh, J., Pritchard, M., Savage, E., Wade, C., Nair, P., Adenwala, A., Lee, L., Malloy, M., Taner, I. and Frilander, M., ‘Linkages between large-scale infrastructure development and conflict dynamics in East Africa’, Journal of Infrastructure Development, Vol. 11, Nos 1–2, 2019, pp. 1–13.

30. Faleg, G. and Palleschi, C., ‘African strategies: European and global approaches towards sub-Saharan Africa’, Chaillot Paper No 158, EUISS, June 2020 (https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/ CP_158.pdf).

31. Iacoella, F., Martorano, B., Metzger, L. and Sanfilippo, M., ‘Chinese official finance and political participation in Africa’, European Economic Review, Vol. 136, 2021.

32. There are expected to be 824 million urban dwellers in 2030 and 1.5 billion in 2050, in comparison to 548 million in 2018. See: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, World Urbanization Prospects – The 2018 revision, 2019 (https://population.un.org/wup/ Publications/Files/WUP2018-Report.pdf).

33. Lall, S. V., Henderson, J. V. and Venables, A. J., Africa’s Cities – Opening doors to the world, World Bank, 2017 (https://openknowledge.worldbank. org/handle/10986/25896).

34. Palleschi, C. and Sempijja, N., ‘Cities’ in Faleg, G. (ed.), ‘African Spaces’, Chaillot Paper No 173, EUISS, March 2022 (https://www.iss.europa.eu/ sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/CP_173_0.pdf).

35. Hughes, K., ‘EU-Africa relations: Strategies for a renewed partnership’, Friends of Europe, May 2017 (https://www.friendsofeurope.org/insights/ eu-africa-relations-strategies-for-a-renewed-partnership-what-next- for-relations-between-europe-and-africa/).

36. Raineri, L. and Bâ, Y., ‘Hybrid governance and mobility in the Sahel: Stabilisation practices put to the test’, in Venturi, B. (ed.), Governance and Security in the Sahel: Tackling mobility, demography and climate change, Istituto Affari Internazionali and Foundation for European Progressive Studies, Brussels–Rome, 2019.

37. ‘African strategies: European and global approaches towards sub- Saharan Africa’, op. cit.

38. High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Joint communication to the European Parliament and the Council – Towards a comprehensive strategy with Africa, JOIN(2020) 4 (https:// eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020JC0004 &from=EN).

39. Baranzelli, C., Kučas, A., Kavalov, B., Maistrali, A., Kompil, M., Oliete Josa, S., Parolin, M. and Lavalle C, European Commission, Directorate-General for International Partnerships, Joint Research Centre, Identification, characterisation and ranking of strategic corridors inAfrica – CUSA project: Phase 1, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2022.

40. Ibid.