You are here

Between a rock and a bullet: security provision and the protection of civilians in the Sahel

Introduction

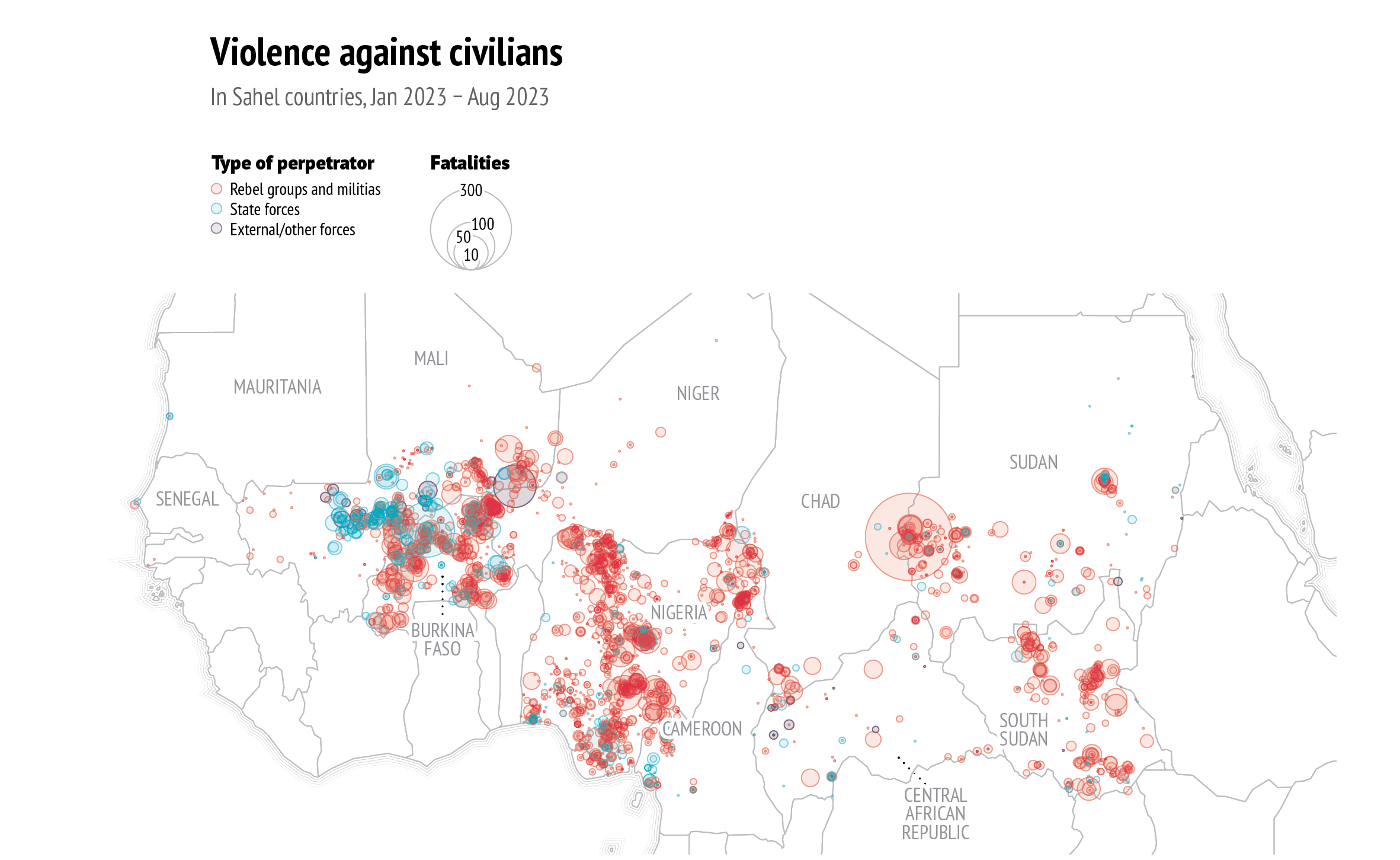

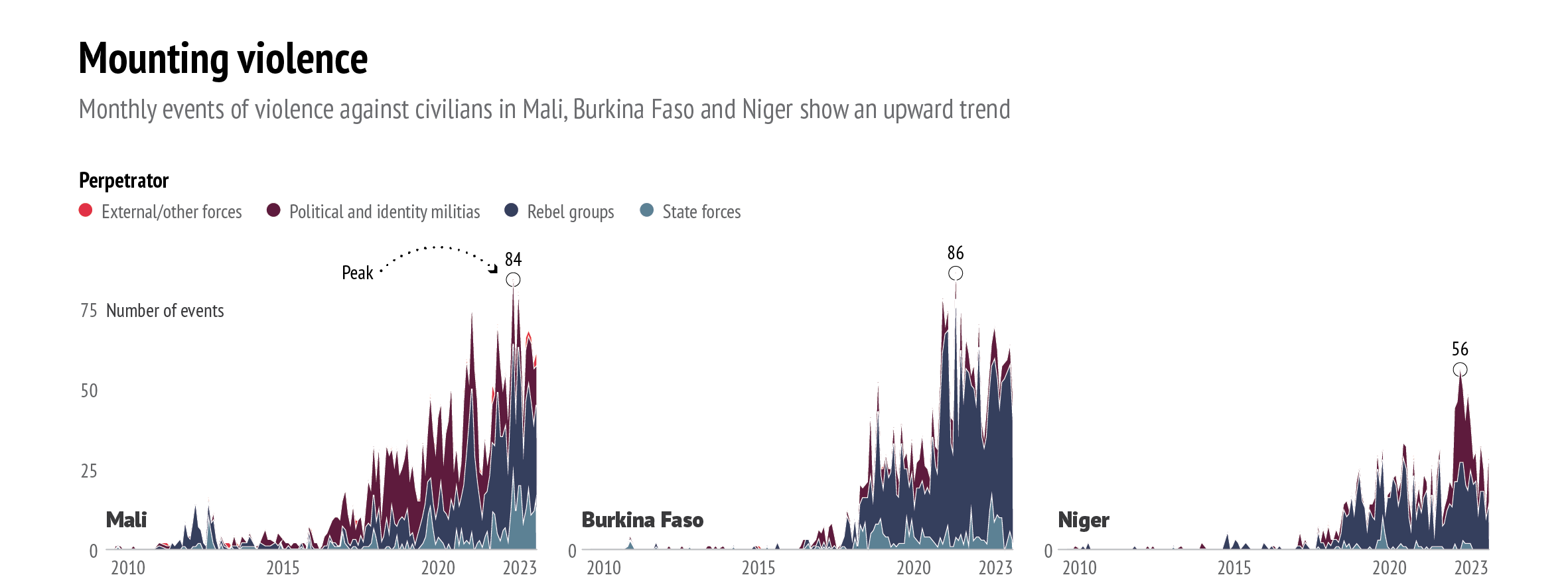

Since 2013, violence against civilians in the G5 Sahel countries – comprising Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger – has increased tenfold (1). With the departure of the French army and the ongoing withdrawal of the UN Peacekeeping Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), jihadist armed groups have once again extended their territorial control and encircled key cities. The 2015 Algiers Accord for Peace and Reconciliation in Mali that was signed by the Malian government and the coalitions of armed groups active in Northern Mali, the so-called signatory movements, is now in tatters. As Mali’s transitional authorities ramp up their military clampdown, and tensions mount in both Burkina Faso and Niger, it is once again the civilian populations who will pay the price of war (2).

In this Brief, we contend that – while far from straightforward – the effective protection of civilian populations could offer a critical step towards diminishing the competition between state, insurgent, and self-defence groups over the provision of security in Sahelian states (3). On these grounds, we argue that civilian protection could offer a route for the gradual re-legitimisation of state security forces in the region. To make this case, we identify principal perpetrators of violence against civilians before outlining three possible trajectories and their implications for security provision and civilian protection. Building on this analysis, we make the case that by eliminating a key source of competition between rival factions, a focus on the protection of civilians may help to break the escalating cycle of violence in the region.

Safety under siege

A key feature of the security crisis in the Sahel is that all belligerents perpetrate violence against civilian populations. Among these, non-state armed groups, including several of the signatories to the 2015 Algiers Accord, are responsible for serious human rights violations, including summary executions, torture and the unlawful recruitment and use of child soldiers. In 2022, Islamist armed groups aligned with the Islamic State Sahel Province (ISSP) – a Salafi-jihadist militant group that is the Sahelian affiliate of the Islamic State (IS) – attacked dozens of villages and massacred scores of civilians in Mali’s Ménaka and Gao regions. Since August 2023, Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), an offshoot of al-Qaeda in the Maghreb (AQIM), has put Timbuktu under siege, forcing more than 34 000 residents to flee the city (4).

Ethnic militias across the region, usually formed to safeguard against self-defence groups set up by other communities, have proliferated. In central Mali, the Dan Na Ambassagou militia, a Dogon community self-defence group, has been targeting Fulani communities for several years and was allegedly responsible for the massacres at Koulogon and Ogossagou in January and March 2019 (5). In Burkina Faso, the government-sponsored Volunteers for the Defence of the Country (VDP), a vigilante group that was formally created under a 2020 law, has reportedly been involved in repeated episodes of violence against civilians. The most recent such episode was the massacre of 150 people in Karma village in April 2023 (6).

Data: ACLED, 2023; European Commission, GISCO, 2023

Under the cover of counter-insurgency operations, state security forces across the Sahel have engaged in human rights violations that may amount to war crimes. According to a 2022 UN report, 35 % of human rights violations in Mali were committed by state security forces (7). Unfortunately, this is a pervasive pattern in the context of African guerrilla warfare where rebels are prone to hiding among civilian communities, the state security forces are often ethnically biased, and nation-building processes remain incomplete. In this context, indiscriminate, state-sponsored violence is a key push factor towards radicalisation, as an increasing number of civilians join jihadist groups in their quest for the most basic levels of security (8).

In addition, Kremlin-backed paramilitaries known as the Wagner Group, who have been deployed in Mali since 2021, have committed widespread rapes and killings of civilians. On 27 March 2022, Malian armed forces, aided by Wagner Group fighters, executed several hundred civilians in Moura village (9). As this harrowing event reveals, the Wagner Group’s violent abuse of civilians has not only been tolerated but systematically solicited and covered up by the Malian authorities (10).

Additionally, the lack of legal accountability has increasingly become the norm since the military takeover of governing institutions in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger. This has been aggravated by the decision of the authorities in Mali and Burkina Faso to opt for a full-scale war against the jihadi armed groups. While the EU’s approach to the Sahel conflict is based on the security-development nexus, the region’s current military rulers have increasingly assumed an aggressive anti-human rights posture while relying on the largely indiscriminate use of force.

Trust for stability

There is a broad consensus that tackling an asymmetric security crisis like the one in the Sahel requires the full buy-in of the local population. The complete lack of trust between the civilian communities and states of the Sahel has not only fostered recruitment into the ranks of jihadist groups but also fuelled an intense competition between state and non-state actors over the provision of security.

As the counter-insurgency operations stigmatise mainly the Tuareg and Fulani communities, some of the Tuareg rebels who signed the Algiers Accord are now back on the warpath in northern Mali (11). A significant portion of jihadist fighters are of Fulani origin (12), a reflection of the fact that the state security forces and ethnic militias have been targeting this community since the start of the conflict (13).

Data: ACLED, 2023

In this context, a specific focus on protecting civilians could help re-establish trust between the civilian population and the state, thus diminishing the potency of security provision as a driving force of competition between the rival factions. While far from simple, the successful protection of civilians may thus be a critical step in the stalled effort to break the escalating cycle of violence in the region. This would also critically reduce the recruitment appeal of armed groups and constitute a fundamental step towards the re-legitimisation of state security forces.

Three (security) futures

Given the current conflict landscape in the Sahel, we identify three possible future security trajectories over the next five years.

Scenario 1: State security forces prevail. In this first scenario, the military strategy of the Sahelian authorities leads to a progressive defeat of the region’s non-state armed groups. The respective state security forces regain control over most of each country’s territory, ending the counter-insurgency campaigns and the state-sponsored violence against civilians carried out under the guise of securitisation policies. While security conditions would improve in this scenario, revenge attacks and unofficial discriminatory policies against the Fulani and the Tuareg communities could rekindle competition over the provision of security.

Scenario 2: Non-state armed groups prevail. In this second scenario, non-state armed groups extend their territorial control, defeat state security forces, and create a ‘grey zone of control’ across large swathes of Mali and Burkina Faso. Vast parts of these two countries become ‘governed’ by the non-state armed groups. In response to these developments, state security forces, and their affiliated ethnic militias, dramatically increase their indiscriminate attacks against communities suspected of supporting non-state and jihadist groups. Ethnic-based violence becomes widespread, escalates, and spirals into an all-out civil war.

Scenario 3: The status quo remains unchanged. In this third scenario, neither state security forces nor the growing number of non-state armed groups manage to gain the upper hand in the ongoing conflict. The principal conflict parties remain unable to exert decisive territorial control or defeat their military and political opponents. In this projected security scenario, civilian communities remain the primary casualties of the belligerents and their competition over legitimacy, territorial and political control over the next five years.

Policy considerations

For the EU, its Member States, and its African and other international partners, the room for manoeuvre is clearly narrow. The present military rulers in Mali, Burkina Faso (and possibly soon Niger) have turned to Russia for support while severing ties with France, the EU and the UN. With the EU’s suspension of most of its assistance to Mali, Burkina Faso, and more recently Niger, the G5-Sahel is now little more than an empty shell. EU sanctions continue to target Malia’s military rulers, a policy that is likely to be extended to Niger’s emergent junta. In this strategic environment, we identify three policy priorities.

Highlight the strategic benefits of civilian protection. In its public diplomacy, the EU together with African partners should take every opportunity to recall that the protection of civilians is an obligation under international humanitarian law and an essential part of the strategic response to the conflict. The EU together with its African and international partners should stress that re-establishing trust between communities and state security forces is key to the de-escalation of the conflict. The successful protection of civilians could reduce the recruitment by armed groups among local communities and improve the relationship between state security forces and communities, thus ending the competition over security provision.

Calibrate strategic communication. Marshalling broader support for the protection of civilians agenda will depend on the ability of the EU and its African and international partners to convey their recognition of the political independence and agency of states in the Sahel region. This will require that the EU, its Member States, and African partners clearly signal their willingness to devise novel avenues of engagement around civilian protection with Sahelian authorities in the altered geopolitical context of the region.

Identify likeminded counterparts. The EU should map out the NGOs (both local and international) that can contribute to the protection of civilians in the present high-risk security environment. It should support local human rights defenders and facilitate their access to the international justice system. The EU should advocate for community-led peacebuilding and constructive engagement between communities and the belligerents. In this regard, it should draw the lessons from the various local mediation initiatives undertaken over the past ten years (14). It should also immediately call on all parties to facilitate humanitarian access.

References

1. ACLED, ‘State Atrocities in the Sahel: The impetus for counterinsurgency results is fuelling government attacks on civilians’, 20 May 2020 (https://acleddata.com/2020/05/20/state-atrocities-in-the-sahel-the- impetus-for-counter-insurgency-results-is-fueling-government- attacks-on-civilians/).

2. Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect, ‘Central Sahel (Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger): Populations at risk’, 31 August 2023, (https:// www.globalr2p.org/countries/mali/).

3. We understand the protection of civilians as the responsibility to protect civilian populations from threats to their physical integrity which, under international law, lies primarily with the state. See: United Nations Department of Peace Operations, ‘The protection of civilians in United Nations peacekeeping’, 2023 (https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/ files/2023_protection_of_civilians_policy.pdf).

4. ‘Historic Timbuktu endures weeks-long jihadist blockade’, Financial Times, 20 September 2023 (https://www.ft.com/content/07a73c2d-6170- 469d-a5c4-4ba384db9efb).

5. ‘Mali : Dan Na Ambassagou, les massacres et la main de l’État’, Jeune Afrique, 14 December 2022 (https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1400667/ politique/mali-dan-na-ambassagou-les-massacres-et-la-main-de- letat/).

6. UN News, ‘Burkina Faso: UN rights office calls for probe into latest deadly attack on civilians’, 25 April 2023 (https://news.un.org/fr/ story/2023/04/1134517).

7. France 24, ‘Mali questions “credibility” of UN rights report claiming steep rise in civilian killings’, 24 March 2023 (https://www.france24. com/en/africa/20230324-mali-questions-credibility-of-un-rights- report-claiming-steep-rise-in-civilian-killings).

8. United Nations Development Programme, ‘Journey to Extremism in Africa: Pathways to recruitment and disengagement’, 2023 (https:// journey-to-extremism.undp.org/content/v2/downloads/UNDP- JourneyToExtremism-report-2023-english.pdf).

9. Human Rights Watch, ‘Mali: New atrocities by Malian army, apparent Wagner fighters’, 24 July 2023 (https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/07/24/ mali-new-atrocities-malian-army-apparent-wagner-fighters).

10. ‘Wagner, abus de l’armée : la junte au Mali réfute en bloc les accusations’, Le Figaro, 25 November 2022 (https://www.lefigaro.fr/ flash-actu/wagner-abus-de-l-armee-la-junte-au-mali-refute-en- bloc-les-accusations-20221125).

11. ‘Au Mali, les ex-rebelles du Nord appellent les Touareg à « contribuer à l’effort de guerre » contre la junte’, Le Monde, 12 September 2023 (https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2023/09/12/au-mali-les-ex- rebelles-du-nord-appellent-les-touareg-a-contribuer-a-l-effort-de- guerre-contre-la-junte_6188939_3212.html).

12. Ghaly Cissé, M., ‘Understanding Fulani perspectives on the Sahel crisis’, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 22 April 2020 (https://africacenter. org/spotlight/understanding-fulani-perspectives-sahel-crisis/).

13. Ahmadou Aly Mbaye, A. and Signé, L., ‘Climate change, development, and conflict-fragility nexus in the Sahel’, Brookings Global Working Paper #169, March 2022 (https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/ uploads/2022/03/Climate-development-Sahel_Final.pdf).

14. See, for instance, ‘La médiation des conflits locaux au Sahel, Burkina Faso, Mali & Niger’, Centre pour le Dialogue Humanitaire, 12 July 2022 (https ://hdcentre.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/HDC- PUBLICATION-mediationconflits-Sahel-WEB.pdf).