You are here

New wine in old bottles?

Introduction

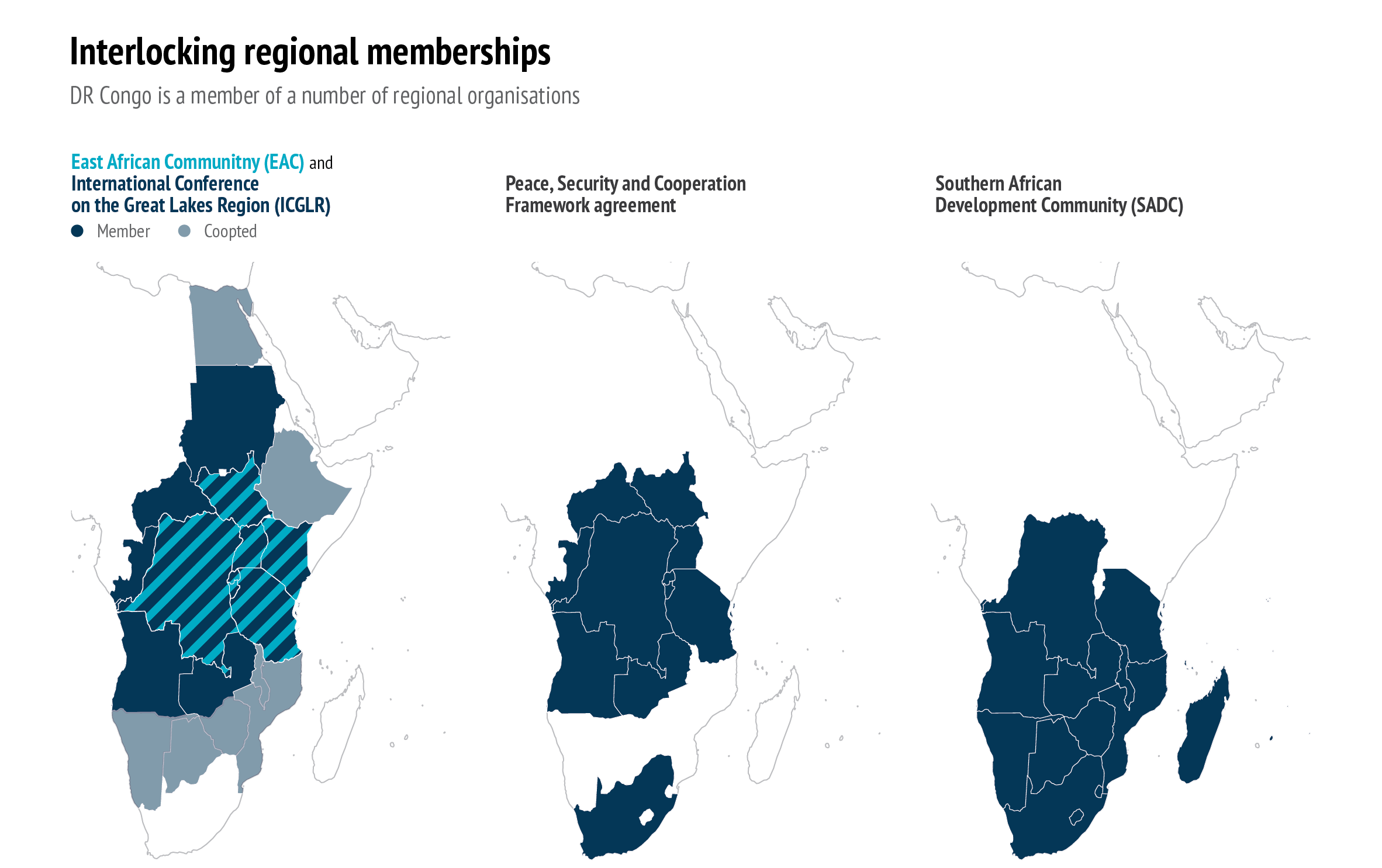

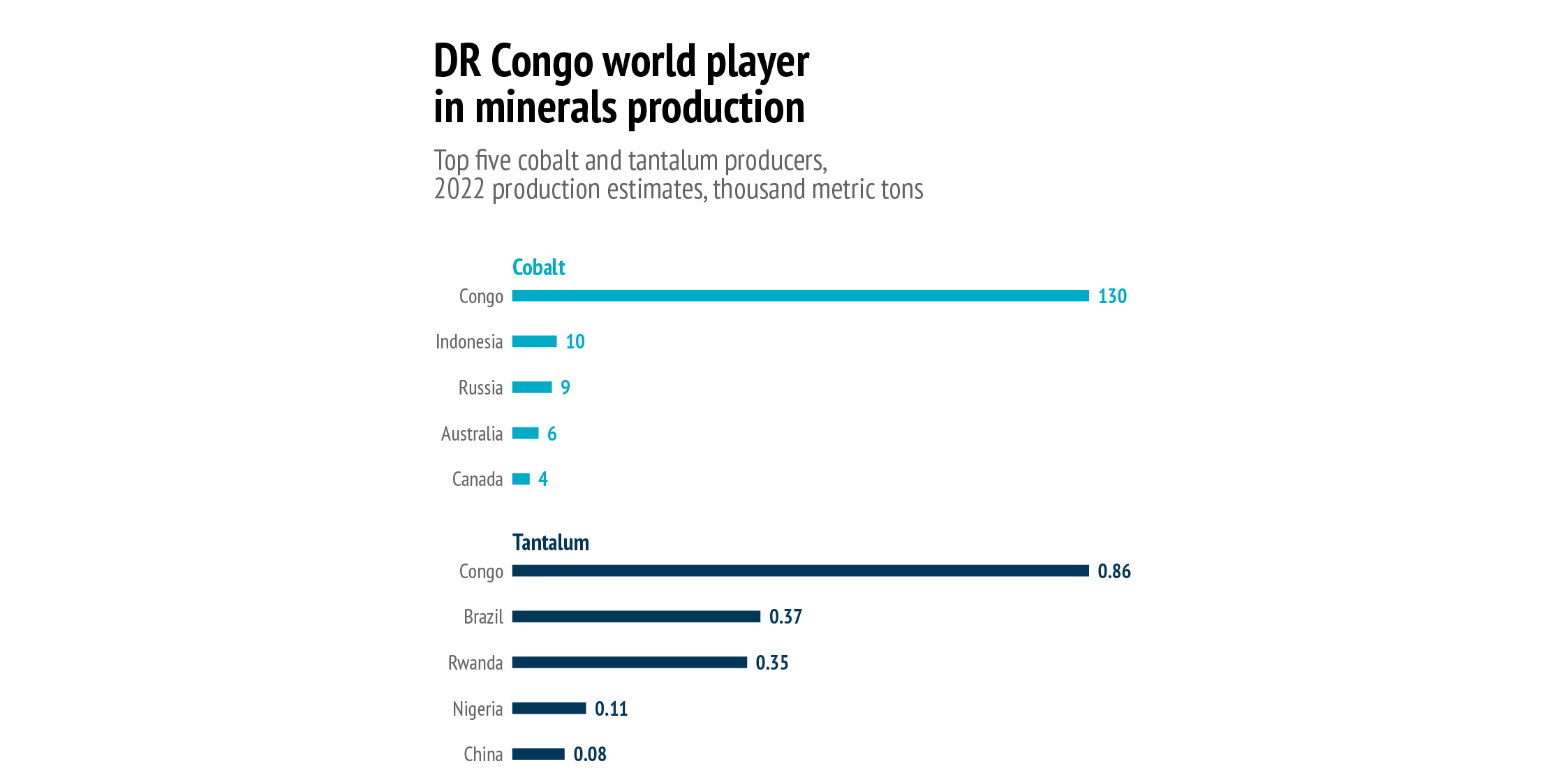

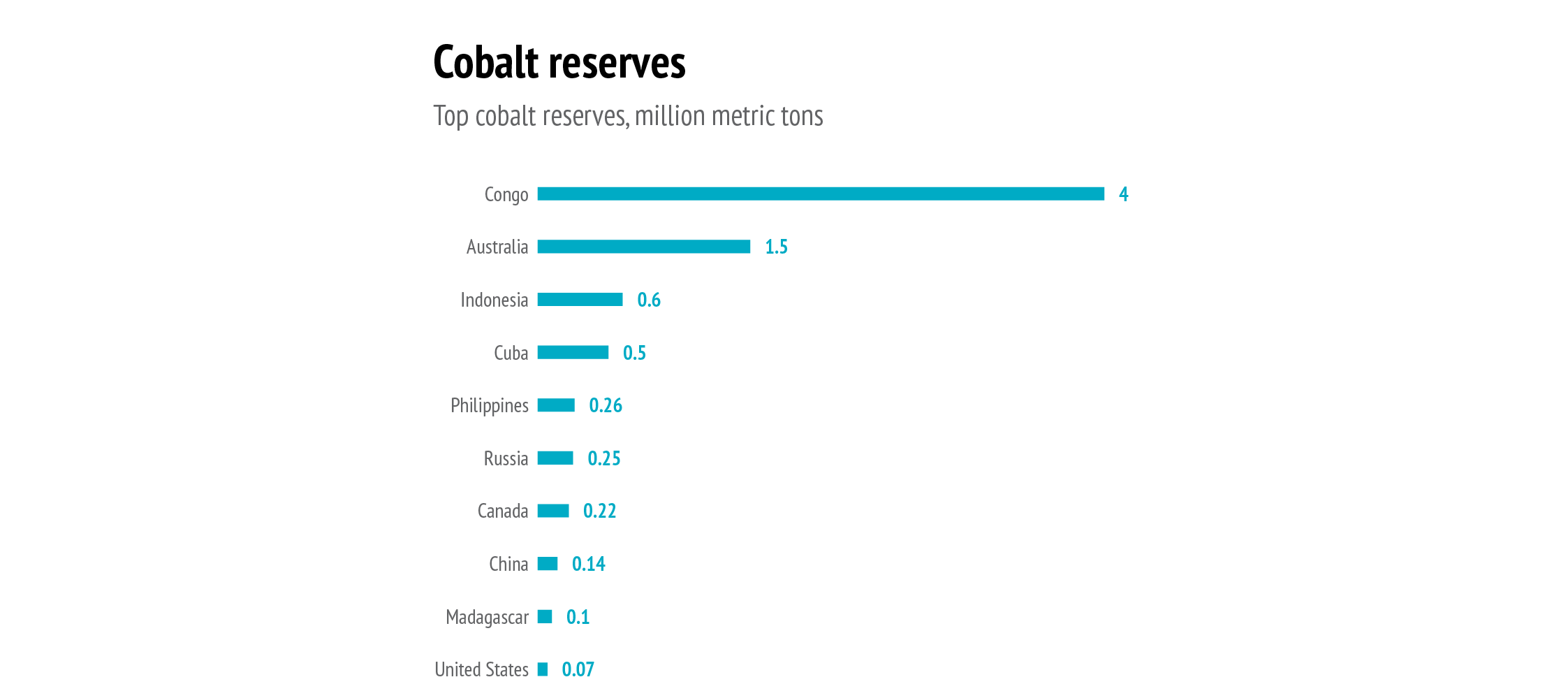

Ten years after the EU published its first strategic framework for the Great Lakes region in 2013 (1), the Council of the European Union released a ‘Renewed EU Great Lakes Strategy’ on 20 February this year. Whereas the root causes of the problems that need to be addressed in the region are discouragingly similar to those of 2013, the international context is not. This renewed strategy comes amid a climate of intensified great power competition, where Africa as a continent has been pushed to the forefront of the international scene, due to its diplomatic weight, exponential demographic growth and, most importantly, abundance of natural resources (2). The latter aspect is particularly salient in the Great Lakes region, and especially in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), a country which hosts large reserves of gold, approximately 8 % of the world’s tantalum reserves, 50 % of the world’s cobalt reserves (3), extensive lithium, and oil and natural gas deposits estimated to be worth over USD 600 billion (4). Appreciation of the importance of this wealth of natural resources is clearly reflected in the new EU strategy for the region.

The Great Lakes region was defined as a strategic priority for the EU in the first ‘Strategic Framework’ a decade ago, which came to notable expression in the efforts undertaken and the resources spent by the Union in the region. It is in the DRC that the EU conducted its first Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) mission outside of Europe in 2003 (5), which was followed by four additional ones (6) in the succeeding years, making the DRC the recipient of the largest number of EU CSDP missions in any one single country (7). During the decade since that strategy was released however, the EU’s focus arguably drifted to the overlapping crises unfolding in the Sahel, a region closer to home. As a result, the Sahel has seen the deployment of four CSDP missions since 2012, while those in the DRC have been wound down. Yet, according to the new strategy, 20 years since it deployed its first CSDP mission to the DRC, the Great Lakes region remains a strategic priority for the EU. What is actually new in the recently unveiled strategy and how have priorities changed compared to the past?

This Brief seeks to address these questions by exploring implementation aspects and implications of the EU’s new strategy for the region, while highlighting challenges and possible ways forward. It is structured in four sections. First, it situates the recent strategy in a changing local, regional and international context.

Second, it compares the two strategies from 2013 and 2023, highlighting similarities and differences. Third, it delves deeper into the three main themes of the new strategy, before identifying challenges for implementation in the fourth section. The conclusion provides an assessment of the EU’s impact on regional dynamics and looks ahead while outlining some recommendations.

Changing local, regional, and international dynamics

In the decade since the first EU strategic framework was published, the region has experienced continuous instability and interwoven political, security and health crises, with a resurgence of violence in the east of the DRC since late 2021. While two of the longest serving presidents of the continent, Paul Kagame in Rwanda constitutional changes making it possible for them to stay in office for the foreseeable future (8), somewhat unexpected shifts in power have occurred in Burundi and the DRC. In Burundi, the former president Pierre Nkurunziza pushed through an unconstitutional third mandate resulting in a severe political and security crisis, including a failed coup attempt (9), before his abrupt death prematurely ushered in his successor in 2020 (10). International actors broadly ceased collaboration with Burundi in the wake of the 2015 crisis, with the EU evoking article 96 of the Cotonou agreement (11), effectively suspending direct financial support to the Burundian administration. The sanctions remained in place for almost 6 years until they were lifted in February 2022 (12).

The EU’s new strategy comes at a moment of renewed tension and instability in the region.

In neighbouring DRC, former President Kabila’s stratégie de glissement (13), whereby he used delaying tactics to postpone elections and remain in power, eventually resulted in an unexpected deal through which the son of Kabila’s long-standing opponent, Félix Tshisekedi, managed to disregard election results and take power in January 2019 (14). African and Western multilateral institutions (including the EU), and bilateral partners endorsed Tshisekedi’s much contested ‘victory’ to avoid chaos and violence in the short term (15). Yet regional instability has prevailed, with an upsurge in violence over the past year and a half, particularly in the east of the DRC, a region in which the number of armed non-state groups has proliferated over the past three decades. The latest bouts of violence have flared up as a result of the revival of the rebel group and Yoweri Musveni in Uganda, remain in place, with M23 in November 2021, again proven to be backed by the Rwandan regime, almost a decade after it was dismantled following a joint military action between the UN’s robust Force Intervention Brigade (FIB), and the Congolese army, FARDC (16).

Data: European Commission, GISCO, 2023

The EU’s new strategy thus comes at a moment of renewed tension and instability in the region, while it also needs to be seen in the context of intensifying great power competition. Over the past year both Western and Russian actors have increased visits to African partners with the US Secretary of State Antony Blinken visiting the African continent an unprecedented three times last year, while the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sergueï Lavrov, has travelled to more than ten African countries since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, including Uganda, Congo Brazzaville and Angola (17). The EU’s deployment of two new military missions in Mozambique and in Niger, as well as its promise to provide lethal equipment through the European Peace Facility (EPF) to Niger and Somalia should also, at least partly, be seen through the prism of a quest for maintaining influence in the continent. While some of these developments may have been a long time in the making given the strong increase of violent extremism trends on the continent – 300 % in the past decade with the Sahel region and Somalia being disproportionately affected (18) – the intensification of global power competition brought about by the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has nevertheless amplified their importance, especially since Uganda, Tanzania and Burundi abstained from voting against the Russian invasion in the first UN General Assembly vote (19).

At the same time, in the world mining industry, China has consolidated its control of refining of cobalt and, to a lesser extent, of its supply from the DRC. The Great Lakes region more specifically also remains at the centre of the world production of tantalum: in 2021, Rwanda and the DRC produced 46 % of the world output, with China as an important buyer (20). The EU’s renewed strategy for the Great Lakes region is likely to be perceived by both the countries in the region and non-Western powers as part of the growing competition for influence. So, to what extent does the new strategy capture these developments, in comparison with the old one?

What's new in the renewed strategy and what lies ahead?

The key topics addressed in the new strategy are, hardly surprisingly given the current context, the same as a decade ago. They include the conflict in the east of the DRC, the increasing number of Internally Displaced People (IDPs), the multiplication of armed groups, and the need for Security Sector Reform (SSR) and Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration (DDR). While the geographical scope of the strategy is the Great Lakes region, defined in the 2013 document as encompassing Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda and the eastern provinces of the DRC (21), both documents are principally focused on the DRC, which is congruent with the country’s significance both as the site of most of the natural resources in the region and host to the majority of non-state armed groups – two interrelated factors which notably contribute to the high number of IDPs in the region.

The two strategies concur in their emphasis on promoting human rights, elections and democracy, as well as contributing to a more secure environment through effective SSR and DDR and fighting armed groups. Both texts also highlight the need to rebuild trust between neighbours and underline the importance of respecting territorial integrity, (something that clearly has not been achieved in the past decade), while pledging to fight poverty. There are thus substantive parts of the two documents which are similar despite there being a decade between them. On the one hand, this seems unavoidable, given that (i) the EU’s normative identity remains the same, and (ii) the root causes of the current instability in the region remain largely unchanged. On the other hand, if the causes remain the same, we may expect the new strategy to suggest new tools to address these. A few novel aspects are noteworthy in the new strategy.

The new strategy puts more emphasis on the management of natural resources and economic integration as a basis for regional collaboration as compared to its 2013 predecessor. There is also more overt language around the fact that the EU, like other external actors, also has economic and geostrategic interests in the region, even though this remains couched in win-win and local ownership terms. The new strategy has three different thematic sections, which appear to signal successive phases in the deployment of EU actions. Below, we assess the main changes compared with the 2013 strategy and relate these to the evolution in regional and international dynamics summarised above.

Return to peace and stability

The new strategy focuses less on issues of governance reform and democratisation than its 2013 predecessor. It also takes a slightly different angle in addressing peace and security at the regional level. These new positions, criticised by NGOs (22), probably reflect the increasing competition from other international actors for whom governance and democratisation are not a priority, and as a result, the weakened leverage of the EU on these issues. Root causes of insecurity and instability in the region such as corruption or a lack of inclusive institutions are for example mentioned in paragraph 4 but not addressed in the following sections.

The peace and dialogue initiatives in the region ultimately depend on the political will of the local actors.

The 2013 strategy was clearly inspired by the comprehensive ‘Peace, Security and Cooperation Framework agreement’ (PSCF) concluded in Addis Ababa on 24 February 2013 to put an end to the previous M23 crisis in the area, for which a special UN envoy for the Great Lakes was appointed. The new strategy, however, hardly mentions the PSCF and seems to rely more on dialogue between the individual states in the Great Lakes Region than on a regional mechanism even if regional conferences and institutions are considered to be partners for the strategy. Initiatives taken by regional mechanisms and organisations have yielded mitigated results in the past because Member States’ national interests have always prevailed over the genuine search for a regional solution.

According to the new strategy, the EU supports existing peace and mediation initiatives, and is willing to step up its engagement in mediation and dialogue, between states, and at the regional level: Only a credible and inclusive dialogue between the countries of the region, matched when needed by national reconciliation efforts in each country, can restore and strengthen mutual trust and confidence (23).

To increase its regional impact, as mentioned above, a proposal is on the table to assign an EU Special Representative for the Great Lakes region, who would be appointed by the European Council and would benefit from some degree of autonomy and budgetary independence from the European External Action Service (EEAS) (24). Much will depend on the specific personality of the Special Representative, the perception the actors in the region have of the representative’s impartiality, on his/her relations with the EEAS and the Council, and the policy instruments he/she will be able to mobilise to support EU regional options, for the appointee to have a constructive impact on the ground.

From trafficking to trade and sustainable development

The second and third thematic subsections in the renewed strategy express the core idea of putting the issue of natural resources management at the centre of the peace process in the region. In this way, the new strategy presents regional economic initiatives as crucial to transform the root causes of the conflict into shared opportunities. This is an important change in perspective compared to 2013 and coincides with increased efforts by the EU to ensure access to strategic and critical raw materials. In particular, the second subsection of the 2023 strategy underlines EU support for the development of clean local and international natural resources value chains in line with EU legislation and International Conference of the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) certification mechanisms, applying OECD-defined due diligence. The current main existing instrument used by the EU is the Conflict Minerals Regulation which came into force on 1 January 2021 (25).

Data: USGS, 2023

It has been criticised for its ineffectiveness in obtaining more transparency in the supply chain (26), and for the lack of an effective sanctioning mechanism for non-compliance (27). An ongoing reform process based on lessons learned since its implementation started may improve the regulation’s effectiveness. Similarly, the renewed strategy mentions EU support for cooperation in the management of joint environmental resources, but no specific policy instruments are mentioned.

From competition to cooperation and integration

This third subsection advocates for trade liberalisation, linking up with the global economy, and regional integration, as guarantees for durable peace. This seems to mirror the thinking behind the creation of the EU after World War II and is widely shared by the ‘international community’. The specific instruments are Team Europe Initiatives (28), and the Global Gateway (29). Within the Team Europe Initiatives, one specifically targets peace and security in the Great Lakes region, referring to regional trade in the mineral sector and bilateral partnerships on sustainable raw materials value chains (30). It is difficult not to make the link with a parallel initiative undertaken by the EU on critical raw materials, which dates back to 2008 when the EU started its raw materials diplomacy (31). On 16 March 2023, the European Commission published a proposal for a European Critical Raw Materials Act to ensure responsible value chains for critical (32), and strategic (33), raw materials (34).

In the context of the Great Lakes, critical raw materials are tantalum, tungsten and niobium, among which tungsten is also a strategic metal. On this issue, the EU is following a new path by clearly and openly defining its own interests when concluding partnerships.

For the Great Lakes, the relevant issues in the Global Gateway are regional integration and production and trade facilitation. Some Global Gateway projects support what are called strategic transport corridors. In the Great Lakes context, this refers to linking Kisangani to the Kenyan port of Mombasa (and to the West with Bangui and Douala) (35). A related initiative for regional integration in the area of hydropower is the construction of the Ruzizi III power dam on the border between the DRC and Burundi, funded by the EU-Africa Infrastructure Trust Fund (36). It will in any case be important to align regional trade and cooperation initiatives and projects with the specific needs of the local communities, and not to neglect national priorities.

Data: USGS, 2023

Challenges ahead

The following section tries to identify overarching challenges for the EU’s regional strategy, followed by more specific comments on possible challenges for the implementation of each of the goals defined in the three aforementioned subsections of the renewed strategy, partly linked to shifting geopolitical dynamics.

An alignment of the EU Member States behind any regional strategy for the Great Lakes is difficult to reach, since they are divided over the causes of the conflict in the Great Lakes, as well as the responsibilities of the various actors, and are unequally committed to finding durable solutions. These divisions explain why the regional ‘strategy’ is vague, covers many topics and allows for different initiatives to be part of its implementation. However, even a more specific and concrete strategy will be confronted with constraints when it comes to implementation.

A major difficulty for the strategy’s first subsection on security and stability relates to the EU’s limited ability to exert influence in the region and local actors’ lack of political will. The EU’s ability to exert influence over states in the region is limited by the fact that these states are only marginally dependent upon the EU – reflecting the shifting geopolitics referred to above. The EU’s perceived hypocrisy with regard to regional dynamics may also pose obstacles to the implementation of the strategy. A case in point is Rwanda: despite several UN Group of Expert reports documenting the obvious support from Rwanda for the M23 movement occupying part of DRC territory and formal condemnation from the EU and EU Member States, no action was taken to force Rwanda out of the DRC. Instead, Rwanda received €20 million from the EPF to support its intervention to fight jihadist movements in Mozambique in December 2022 (37). Although the EU in Kinshasa has since pushed for another €20 million from the EPF for military equipment in Kindu in the DRC to balance the much criticised support to Rwanda (38), this example shows that as long as it remains unable or unwilling to put tangible pressure on the parties involved it will be very difficult for the EU to position itself as a neutral actor capable of providing a framework for dialogue. It is more likely that the EU will support existing regional initiatives and dialogues while enhancing coordination between the various EU delegations to implement the outcomes of regional dialogues convened by other actors. The peace and dialogue initiatives in the region ultimately depend on the political will of the local actors.

The second subsection ‘From trafficking to trade’ is also likely to feature implementation challenges. Despite various initiatives taken to ensure respect for OECD-defined due diligence guidelines on the mining sites where 3T (tin, tungsten, tantalum) are bought, high levels of smuggling towards the neighbouring countries continue. Congolese authorities and experts have therefore levelled criticism against certification mechanisms which are applied in the DRC and supported by the local authorities, but not applied to the minerals smuggled to countries including Rwanda or Uganda where they are considered legal when exported. To counter this problem, in January 2023, a joint venture was created between Primera Group, a company based in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and the DRC state, to create a company called Primera Gold which buys gold from artisanal mines in eastern DRC to sell and refine it in the UAE. The initiative is applauded in the DRC because it has made it possible to withdraw important quantities of gold from the smuggling circuit and keep it (39), at least in principle, in the hands of the DRC. A similar initiative is being undertaken for the 3T metals. This operation, which could possibly be the blueprint for the future artisanal mining sector in the DRC, shows the partial failure of existing certification and validation systems introduced with the aim to reduce conflict, as well as the increasing leverage of non-Western actors who may be reluctant to implement due diligence systems considered to be Western inventions.

The harmonisation of local and regional needs will be a huge challenge.

The third subsection ‘From competition to cooperation and integration’ which addresses the changing geopolitical (and geoeconomic) situation in the Great Lakes by underlining regional trade, interconnectedness and investment is also likely to face implementation challenges. The strategy refers to the EU’s Global Gateway Investment Package which is meant to be a more attractive, albeit much belated, alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) investment strategy in Africa. Yet, if this policy is to be successful the EU will have to do much better than its Chinese counterpart which has made significant strides ahead of it in the infrastructure sector. In this regard, previously formulated criticisms of EU policy may still apply and must be addressed: specifically, allegations that EU policies are driven by the priorities of external donors rather than by internal demand (40), that they are primarily defined by the EU’s own development needs and objectives (41), and that they are premised on technical approaches that eschew political engagement (42). Finally, regional trade and integration do not necessarily constitute a guarantee of peace: initiatives instigated by President Tshisekedi for economic cooperation with his neighbour countries have not been able to prevent the ongoing M23 crisis. Indeed, strategic, demographic or security interests or for that matter interests linked to the informal smuggling economy may prevail over formal economic ones. Furthermore, initiatives linked to support for strategic corridors may supersede local interests: the DRC may have a stronger interest in linking up its own national transport network, fostering integration of East Congo within the national economy than with the economy of East Africa (43).

If the EU wants to engage in win-win partnerships on raw materials, it will need to create more favourable options for the partner countries than China has been able to provide. During the 4 March 2023 Kinshasa Economic Forum between the DRC, France and the EU, negotiations were announced between the European Commission and the DRC about a strategic partnership on a responsible value chain for critical raw materials (44). This partnership is focused on cobalt and the production of electric batteries. When applied to the Great Lakes regional strategy, it would concern tantalum as a critical raw material, important for companies such as H.C. Starck in Germany. Such a partnership, to ensure responsible and stable supply in critical raw materials, could possibly be based on partnerships with companies such as Primera, or on industrial exploitation projects, provided attention is paid to due diligence standards appropriated by the local actors. Projects based on productive investment in East Congo are officially on the table (45). However, the current challenges linked to security, the business climate, and performance of local government administration are still noteworthy. In the meantime, Rwanda is considered as an island of stability and efficiency and has until now been able to ensure regular (but not responsible) supply of these raw materials (46), while the buyers and the EU have turned a blind eye to the illicit nature of their sources of supply.

Conclusion

Due to the structural constraints of the EU, where a consensus between 27 Member States is necessarily broad and general, to call the 14-page document a strategy is maybe a bridge too far – it is rather a framework for action, a reference document for activities to be undertaken by the EU at the regional level in the Great Lakes. It is indeed hard to imagine that the 27 EU Member States could agree on specific objectives to be attained in a given time period with specified targets for the short, medium and long term as a strategy would usually require. However, given the specific country-level outlook from the various EU delegations in the Great Lakes region, this document does answer the need for a regional coordinating perspective, using several new EU policy tools which did not exist when the previous document was published. According to EU officials involved in the drafting process, the strategy was devised with a view to allowing for the development of EU action over time and thus the prospect of an evolving policy approach that connects the short, medium and long term. It was the result of a long negotiation process with the EU Member States, EU delegations, civil society and Member States’ Special Envoys for the Great Lakes. The precise implications of the implementation of the new strategy for the EU’s engagement in the region will hopefully become clearer in the future as Member States currently seem to prefer to wait until after the DRC elections in December.

The key challenge for the strategy to be credible will be the alignment of the various national strategies with the regional objectives. It will be necessary to use adapted tools for the strategy, in which the appointment of a skilled and experienced Special Representative, with a thorough knowledge of the Great Lakes and its history, seems essential. Existing tools will have to be carefully matched to local needs and priorities if they are to be effective, yet the harmonisation of local and regional needs will be a huge challenge.

An efficient and well-coordinated effort to communicate the new strategy will also be necessary in the current anti-Western climate where wild conspiracy theories flourish. This is not an easy task at the regional level where any statement can be misinterpreted. More specifically, for the second axis, investments are needed in the industrialisation of the – hitherto – artisanal mining sector. Several initiatives have been undertaken to apply due diligence in this sector, which are increasingly perceived as normative external constraints. To avoid due diligence being delegitimised and for the sake of efficiency, the EU will have to integrate the concept in the new initiatives it undertakes and to harmonise it with initiatives taken at the DRC national level.

For the third axis of regional trade and integration, the economic and trade position of the DRC must be reinforced so that it can act at an equal level with its regional partners. To achieve this, the varied needs of the diverse Great Lakes member countries must be reckoned with, and efforts made to identify common interests. Any effort at integration must build on the reality on the ground and not on externally formulated principles and declarations.

References

1. EU Commission, ‘A Strategic Framework for the Great Lakes Region’, JOIN (2013) 23 final, 19 June 2013 (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal- content/HR/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52013JC0023).

2. Wilén. N., ‘“Times they are a-changin”: Africa at the centre stage of the new (il)liberal world order’, Egmont Policy Brief, No 293, Egmont Royal Institute for International Relations, Brussels, 2022.

3. US Geological Survey, ‘Mineral Commodity Summaries’, January 2022 (https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2022/mcs2022-cobalt.pdf).

4. Kavanagh, M.J., ‘650 billion worth of oil reserves are being auctioned in Congo’, Bloomberg, 16 May 2022 (https://www.bloomberg.com/news/ articles/2022-05-16/congo-says-oil-block-tenders-hold-16-billion- barrels-of-reserves?leadSource=uverify%20wall).

5. EUFOR ARTEMIS.

6. EUFOR DR Congo, EUSEC DR Congo, EUPOL Kinshasa and EUPOL DR Congo.

7. Arnould, V. and Vlassenroot, K., ‘EU policies in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Try and fail?’ Security In Transition, No 6, European Research Council, London, February 2016 (https://www.egmontinstitute.be/eu- policies-in-the-democratic-republic-of-congo-try-and-fail/).

8. Adebayo, B., ‘Uganda court upholds law that could allow Yoweri Museveni be President for life’, CNN, 27 July 2018 (https://edition.cnn. com/2018/07/27/africa/uganda-presidential-age-limit/index.html).

9. Wilén, N. ‘Burundi’s military still key to stability amid political crisis’, World Politics Review, 2 June 2015 (https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/ burundi-s-military-still-key-to-stability-amid-political-crisis/).

10. UN, ‘UN Commission of Inquiry on Burundi: The electoral campaign is marred by a spiral of violence and political intolerance’, 14 May 2020 (https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2020/05/un-commission- inquiry-burundi-electoral-campaign-marred-spiral-violence-and).

11. Council of the EU, ‘Burundi: EU closes consultations under Article 96 of the Cotonou Agreement’, 14 March 2016 (https://www.consilium. europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/03/14/burundi-eu-closes- consultations-cotonou-agreement/).

12. Council of the AU, ‘Burundi: EU lifts existing restrictions under Article 96 of the ACP-EU Partnership Agreement’, 8 February 2022 (https:// www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/02/08/burundi- eu-lifts-existing-restrictions-under-article-96-of-the-acp-eu- partnership-agreement/).

13. International Crisis Group, ‘Course contre la montre pour un compromis politique en RDC’, 14 December 2016 (https://www.crisisgroup.org/ africa/central-africa/democratic-republic-congo/course-contre-la- montre-pour-un-compromis-politique-en-rdc).

14. Englebert, P., ‘Congo’s 2018 elections: An analysis of implausible results’, African Arguments, 10 January 2019 (https://africanarguments. org/2019/01/drc-election-results-analysis-implausible/).

15. Berwouts, K. and Reyntjens, F., ‘The Democratic Republic of Congo: The Great Electoral Robbery (and how and why Kabila got away with it)’, Egmont Africa Policy Brief, No 25, Egmont Royal Institute for International Relations, Brussels, 19 April 2019.

16. International Crisis Group, ‘Easing the turmoil in the Eastern DR Congo and Great Lakes’, Africa Report, No 181, 25 May 2022. FARDC stands for ‘Forces armées de la République démocratique du Congo’ or the DRC government army.

17. Fabricius, P., ‘Sergey Lavrov back to Africa with a vengeance’, Institute for Security Studies (ISS), 20 January 2023, (https://issafrica.org/iss- today/sergey-lavrov-back-to-africa-with-a-vengeance).

18. Africa Center for Strategic Studies, ‘Sahel and Somalia drive rise in Africa’s militant Islamist Group violence’, 9 August, (https://africacenter. org/spotlight/sahel-and-somalia-drive-uninterrupted-rise-in-african- militant-islamist-group-violence-over-past-decade/).

19. United Nations General Assembly, Eleventh Emergency Special Session, 5th Plenary Meeting, 2 March 2022, Official Record A/ES-11/PV.5, p. 15. (https://daccess-ods.un.org/tmp/5832030.77316284.html).

20. US Geological Survey, ‘Mineral Commodity Summaries. Tantalum 2023’ (https://www.usgs.gov/centers/national-minerals-information- center/niobium-and-tantalum-statistics-and-information); Papp, J.F., ‘Conflict minerals from the Democratic Republic of the Congo – Global

tantalum processing plants, a critical part of the tantalum supply chain’, USGS Fact Sheet 2014-3122, December 2014 (https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/ publication/fs20143122).

21. EU Commission, ‘A Strategic Framework for the Great Lakes Region’, JOIN (2013) 23 final, 19 June 2013 (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal- content/HR/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52013JC0023).

22. EurAc, ‘“Renewed EU Great Lakes strategy”: A missed opportunity for good governance and human rights’, 20 February 2023. (https://www. eurac-network.org/sites/default/files/2023_eurac_eu_renewed_gl_ strategy_statement_en_0.pdf).

23. EU Council Conclusion, ‘A renewed EU Great Lakes strategy: Supporting the transformation of the root causes of instability into shared opportunities’, 6632/23, 20 February 2023, para 19 (https://data. consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-6631-2023-INIT/en/pdf).

24. See European Parliament. Directorate General for External Policies, Policy Department for External Relations, ‘The scope and mandate of EU Special Representatives (EUSR’s)’, 2019, pp. 19 and 26. (https://www.europarl. europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EXPO_STU(2019)603469).

25. ‘Regulation (EU) 2017/821 of the European Parliament and the European Council of 17 May 2017 laying down supply chain due diligence obligations for Union importers of tin, tantalum and tungsten, their ores, and gold originating from conflict-affected and high-risk areas’, Official Journal of the European Union, 19 May 2017 (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/ legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32017R0821).

26. EurAc-IPIS-Pax, ‘The EU Regulation on 3TG minerals: a blueprint for responsible mineral trade?’, Discussion paper on the effectiveness of the European Union Regulation 2017/821, April 2023, p. 16.

27. EurAc-PAX, ‘The EU Conflict Minerals Regulation: Implementation at the EU Member State level’, Brussels, June 2021, p. 12 (https://ipisresearch. be/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Review-paper-on-EU-Conflict- Minerals-Regulation-1-1.pdf).

28. Defined as Flagships that deliver concrete, transformational results for partner countries or regions pursued by European development/ external action partners such as Team Europe. They are based on joint programming by EU components and other European partners. See: https://europa.eu/capacity4dev/tei-jp-tracker/.

29. The Global Gateway funds investments in infrastructure for a wide variety of sectors. In sub-Saharan Africa, it aims to support Africa achieve a strong, inclusive, green and digital recovery and transformation. See: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/stronger-europe-world/global-gateway_en

30. See Team Europe Initiative and Joint Programming Tracker (https:// europa.eu/capacity4dev/tei-jp-tracker/tei/peace-and-security-great- lakes-region-africa).

31. Biedermann, R., ‘The European Union’s raw materials diplomacy: Market access and development?’, European Foreign Affairs Review, Vol. 21, No 2016, p. 116.

32. In terms of economic importance and supply risk.

33. Used in strategic sectors and likely to create supply risks in the near future.

34. European Commission, Press release, ‘Critical raw materials: ensuring secure and sustainable supply chains for the EU’s green and digital future’, 16 March 2023 (https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/ detail/en/ip_23_1661).

35. Oliete Josa, S., ‘The corridor approach as a programmatic tool for EU investments in Africa: challenges and opportunities’, presentation at European Union Infopoint conference on Global Gateway Strategic Corridors, Brussels, 19 April 2023.

36. See European Union Africa Infrastructure Trust Fund, ‘Ruzizi Hydropower’ (https://www.eu-africa-infrastructure-tf.net/activities/ grants/ruzizi.htm).

37. Council of the EU, ‘European Peace Facility: Council adopts assistance measures in support of the armed forces of five countries’, 1 December 2022 (https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press releases/2022/12/01/european-peace-facility-council-adopts-assistance-measures-in-support-of-the-armed-forces-of-five-countries/).

38. ‘EU set to grant €20m to the armed forces’, Africa Intelligence, 18 April 2023 (https://www.africaintelligence.com/central-africa/2023/04/18/eu- set-to-grant-e20m-to-the-armed-forces,109946540-bre).

39. The official gold export from South Kivu in 2022 amounted to a mere 42 kg, while Primera states that it succeeded in exporting 600 kg after four months. See: Depeche.cd, ‘RDC-Minerais: 600,50 kilos d’or exportés en 3 mois, un record équivalent à 26 ans d’exportation au Sud-Kivu’, 21 avril 2023 (https://depeche.cd/2023/04/21/rdc-minerais-60050-kilos-dor- exportes-en-3-mois-un-record-equivalent-a-26-ans-dexportation-au-sud-kivu/).

40. Rayroux, A. and Wilén, N., ‘Resisting ownership: the paralysis of EU peacebuilding in the Congo’, African Security, Vol. 7, No 1, 2014, p. 39.

41. Gibert, M.V., ‘The European Union and the Great Lakes Region: Constraints and inconsistencies’, in Khadiagala, G.M. (ed.), War and Peace in Africa’s Great Lakes Region, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2017, p. 113.

42. ‘EU policies in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Try and fail ?’, op.cit.,p. 12.

43. Byiers, B., et.al., ‘Security through market integration? The political economy of DRC’s accession to the EAC’, Discussion paper No 341, ECDPM, Brussels, April 2023, p. 8.

44. Communiqué de presse conjoint, ‘Engagement à lancer des négociations pour un partenariat stratégique sur la chaîne de valeur de minéraux critiques’, Kinshasa, 4 March 2023.

45. Interview with French Embassy officials in Kinshasa, 17 March 2023.

46. According to the US Geological Survey (data for 2021), the DRC and Rwanda produce 57 % of the world supply (43 % for the DRC, 14 % for Rwanda).