- Beijing has shifted the focus of the US-China tech war from a contest over advanced US and allied technologies to a struggle over low value-added but vital components for all industries. By sharply reducing critical mineral exports to most countries throughout 2025, China forced Washington to retreat from non-negotiable ‘national security’ controls towards ‘G2’ bargaining.

- Europe now faces the dual risk of asymmetrical US restrictions on European tech exports to China’s ‘must-have’ market, and – more dangerously – an emboldened China that knows it can disrupt Europe’s industries at little cost.

- Europe must reindustrialise with partners. Through measures such as local content requirements, the G7+ can leverage its share of over 60% of global GDP to kickstart the production of minerals, foundational chips and other enablers. Europe must expand its industrial niches to prevent even greater asymmetric dependence on Washington. To counter Beijing’s coercive practices, it must activate the anti-coercion instrument.

When Beijing sharply reduced exports of rare earths, germanium and other critical materials throughout 2025, the tech war entered a more dangerous phase. During part one, the first Trump administration and subsequently the Biden administration had insisted that ever more stringent high-tech controls on the transfer of American, European, and other partners’ technologies to China were non-negotiable, invoking national security. The US objective was to maintain – and later maximise – its (military-)technological edge over China.

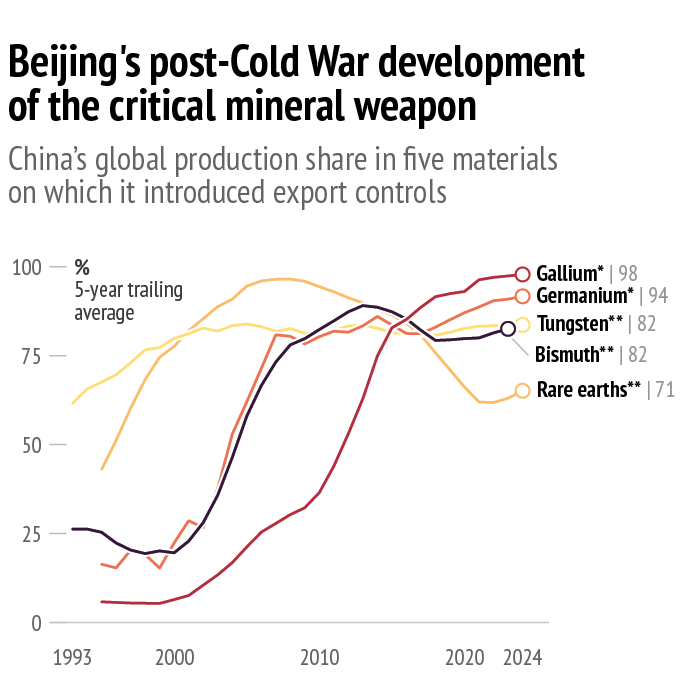

Then China changed the game. What began as a struggle over leading and trailing-edge American and partner high-tech evolved into a contest over access to crucial, but barely lucrative or even unprofitable inputs for all industries. Beijing used the export controls it had gradually introduced between August 2023 and April 2025 to not just squeeze critical mineral supply to the US, but also to most other countries. The stakes are enormous: these materials are the skeleton of our healthcare, energy and weapon systems and of the global economy more broadly. Soon after Beijing cut mineral supplies, President Trump lowered tariffs, again allowed exports of Nvidia’s H20 (and later H200) chips, and rolled back some other tech restrictions.

This Brief tracks the transformation of the US-China tech war to identify the most serious risks for Europe and the options to mitigate them. Europe faces a dual threat. The first stems from a United States that strikes ‘G2’ bargains with Beijing that benefit US tech exports, while retaining the legal tools to block European high-tech exports. More dangerously, Europe confronts an emboldened China that drip-feeds critical minerals to foreign industries.

Throughout 2025, Beijing’s strategy has caused production disruptions around the world, while demonstrating its ability to tighten the thumbscrews with devastating effect – including if Europe protests about China’s military pressure on Taiwan, its below-market price exports or other activities. Yet Beijing has so far skilfully kept Europe’s economic pain below the threshold that would trigger an all-out diversification strategy, while stringing along its industry and political leaders with promises of ‘rare earth dialogues’ and ‘general licences’.

To move supply chain bottlenecks out of China, Europe must reverse its industrial decline.

To move supply chain bottlenecks out of China, Europe must reverse its industrial decline. This requires adopting shared G7 and partner economic security standards, including ‘buy European and partner’ requirements in vital sectors, leveraging defence budgets for innovation and supply chain security, among other measures. Europe should also ensure that Washington does not disproportionately sacrifice Europe’s tech interests. Finally, Member States should pool economic resources to strengthen Europe’s capacity for economic deterrence vis-à-vis China. If these steps are not taken, Europe will likely face even more severe coercion in the near future.

‘As large a lead as possible’

The post-post-Cold War era has already produced two shifts in how the US regulates global technology transfers to China. Between 2017 and the summer of 2025, Washington put in place an increasingly comprehensive system of restrictions primarily designed to prevent Beijing from gaining leadership in artificial intelligence and other emerging disruptive technologies (EDTs). Chinese leadership in EDTs would help the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) close the military-technological gap with the US. Broader dominance in fourth industrial revolution technologies would provide Beijing with greater economic resources than Washington’s, including to finance its defence build-up. Both developments would erode US-led deterrence, especially around Taiwan, where the PLA already enjoys the advantages of geographic proximity, scale and industrial capacity. Both Trump 1.0 and the Biden administration justified technology controls as a matter of national security.

As China asserted itself more forcefully, Trump 1.0 broke with four decades of ‘strategic engagement’ in 2017. Despite its accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO), Beijing’s espionage campaigns, use of local content requirements, and other forms of state support persisted. China’s leaders prioritised building a self-reliant industrial base through programmes such as ‘Made in China 2025’ and the 14th Five-Year Plan over market reforms. President Xi militarised China’s man-made islands in the South China Sea despite his personal (and public) assurances to President Obama(1). The PLA accelerated its modernisation, with a strong buildout of the capabilities that it needs to assert sovereignty over Taiwan. The constitutional amendment of March 2018 which allowed President Xi to remain in power beyond two terms definitively dashed Western hopes of China’s democratisation.

Curtailing tech transfer became a cornerstone of the US pivot to strategic competition. The 2017 US National Security Strategy declared that great power competition had returned, underlining the need to ‘reduce the illicit appropriation of public and private sector technology and technical knowledge by hostile foreign competitors’(2). Trump 1.0 banned sales of US and partner tech to Huawei and related companies. The administration’s entity listings also included PLA-linked research institutes, semiconductor developers, and companies suspected of contributing to surveillance in Xinjiang.

President Biden blocked the export of a wide range of technologies to China in general. Citing a new ‘strategic environment’ following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and PLA exercises around Taiwan, his National Security Advisor advocated ‘maintain[ing] as large a lead as possible’ in foundational technologies(3). By the time President Biden left office, Washington had put a ‘freeze in place’ blocking shipments of AI-accelerators like the Nvidia A100, advanced NAND and DRAM memory chips, lithography and other semiconductor manufacturing equipment, design software and many other inputs(4).

European tech firms know they cannot evade US restrictions.

Washington’s controls and US-led minilateral regimes covered exports of European technologies too. The world relies on ASML’s machines to manufacture roughly 90% of all semiconductors globally. Since 2019, The Hague has withheld an export licence to China for the company’s unique extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography systems. Together with Washington and Tokyo, in 2023 the Netherlands also imposed controls on certain deep ultraviolet (DUV) tools and other trailing-edge lithography systems. These measures can extend to servicing and the supply of spare parts. This gives The Hague – and by extension Washington – the option to take existing semiconductor production capacity in China offline, at least until Chinese competitors figure out how to operate these machines without ASML’s assistance.

European tech firms know they cannot evade US restrictions. The EU’s 2018 attempt to shield its oil majors from renewed US sanctions on Iran failed(5). Europe’s industry bosses, more fearful of ending up in an American prison than of a slap on the wrist from Brussels, halted the development of Iran’s vast oil reserves. Semiconductor ecosystem representatives anticipate that their companies and research institutes will comply with any future US controls, irrespective of EU objections(6).

They also expected President Trump to impose sweeping tariffs, while China hawks in his administration would further tighten technology restrictions further(7). In February, Trump 2.0 even banned export of Nvidia’s less powerful H20 chips to China. More dangerously for Beijing, a vast expansion of US controls on ASML exports to China appeared ‘imminent’ in June of 2025(8). This would have constrained China’s semiconductor ambitions even at more mature nodes. Washington’s push at the time to halt servicing, and perhaps also supply of spare parts, would have taken production capacity in China offline, albeit perhaps only temporarily(9).

Xi’s trump card

The tech war entered a more dangerous phase when Beijing deployed its critical minerals weapon far more extensively than ever before. While Europe acquiesced to Trump’s tariffs, China responded by sharply reducing mineral exports. Beijing’s gamble paid off: Washington retreated from a doctrine of maintaining the largest possible technological lead towards ‘G2’ bargaining. When shortages disrupted US defence and civilian industries, Trump 2.0 reversed several measures, including the H20 ban, and postponed the Affiliates Rule. Beijing thus ensured that Washington’s tech containment, of little interest to President Trump personally, began to undermine US reindustrialisation ambitions, one of his central priorities.

Data: United States Geological Survey, Minerals Yearbook, 1990-2025; British Geological Survey, ‘World Mineral Production’, 1990-2025

China’s material controls and US technological restrictions share important similarities. Both are justified on national security grounds and feature intrusive licensing requirements and military end-use bans. Washington curtailed China’s access to semiconductor manufacturing equipment; Beijing, in turn, blocked access to the machinery needed to produce rare earths. Beijing’s 9 October expansion of rare earth controls (suspended for twelve months following the Trump–Xi meeting) closely mirrored the extraterritorial reach of US measures.

Yet the impact of China’s supply coercion is greater. By withholding rare earths and other inputs like legacy chips, Beijing can cripple entire industries in Europe and beyond. Throughout 2025, China indiscriminately reduced exports to almost all countries. By contrast, US controls have constrained China’s ability to produce cutting-edge technologies like AI chips but have not prevented its broader access to simpler chips crucial for consumer goods, industrial machinery and manufacturing more generally.

President Trump even sought to monetise his policy reversal. Washington again allowed Nvidia to export its H20 chips to China on the condition that the company would pay 15% of the resultant revenue to the US government. More hawkish members of the Trump administration narrowly blocked Nvidia’s last-minute attempt to secure approval for exporting more advanced chips to China before the Trump-Xi meeting. In December Trump also offered Nvidia’s more powerful H200 chips to President Xi, provided the US government receives a 25% fee per sale. In effect, the US is removing obstacles only for US firms to sell powerful hardware to China, undermining the joint European-American interest in preventing China from closing the military-technological gap.

Europe’s way forward

The evolution of the US-China tech war outlined in this Brief comes with dire risks for Europe that must be addressed without delay. Washington can unilaterally decide which European exports reach China, while permitting additional US exports. But the far greater threat stems from China’s control over materials and other industrial inputs. Beijing’s economic arsenal continues to expand. Four decades of industrial policy have left countries deeply dependent on Chinese manufacturing, including increasingly for foundational semiconductors – the central nervous system of the global economy. A growing share of chemical production, the connective tissue of modern industry, has also left Europe.

American and European strategies to reverse the tide remain inadequate. The President’s 2025 Trade Policy Agenda acknowledges the specific threat posed by China, but President Trump launched a trade war against all partners – imposing higher tariffs on India, a key de-risking partner, than on China itself. The EU, meanwhile, produces important strategies like RESourceEU without committing the resources needed to reverse its industrial decline.

To neutralise the threat, Europe and its partners must dismantle China’s supply chain weapons and deter their use before diversification can be fully achieved. First, Europe must take reindustrialisation seriously. Friend-shoring critical minerals is only a starting point. The EU should pursue joint G7 economic security standards that include ‘buy Europe and partner’ procurement requirements and joint tariffs. These steps are necessary to halt the flood of China’s state-supported production of foundational chips, chemicals and other strategically indispensable items. With the G7 and key partners still accounting for over 60% of global GDP, coordinated demand-side measures can reshape markets. The EU should push for a US sectoral tariff exemption for European mineral exports, and if successful, propose the same for semiconductors, chemicals and other essential inputs for US manufacturing. Europe can leverage its rising defence budgets to overcome China’s technological and production chokepoints. Funding dual-use research is possible under NATO’s 3.5% benchmark, while strengthening the defence industrial base is eligible under the 1.5%. G7-countries should also build on their comparative advantages: Europe should secure offtake agreements and co-investment in Japan’s more advanced critical mineral projects.

Second, to manage US transactionalism, European leaders must prevent Washington from sacrificing European exports to China while preserving market access for US firms. At present, Europe’s semiconductor manufacturers rely on sales to China’s ‘must-have’ market to remain competitive. Expanding European control over key niches in global industrial supply chains, on which the US defence sector also relies, can help ensure that Washington takes Europe’s interests into account.

Third, Europe must strengthen economic deterrence. President Xi can mobilise all levers of China’s state power, from export controls to industrial policy, while President Trump also has a wide array of tools at his disposal. Europe’s strategic indispensability matters only if it can credibly threaten to restrict access to its technologies and single market when its interests are violated. Activating the anti-coercion instrument against Beijing is the fastest way to convert Europe’s economic assets into geopolitical power.

References

1. The White House, ‘Remarks by President Obama and President Xi of the People’s Republic of China in Joint Press Conference’, 25 September 2015.

2. The White House, ‘National Security Strategy’, December 2017, pp.21-22.

3. The White House, ‘Remarks by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan at the Special Competitive Studies Project Global Emerging Technologies Summit’, 16 September 2022.

4. Goujon, R., Piper, L.D., Kleinhans, J.P. and Kratz, A., ‘Freeze-in-Place: The impact of US tech controls on China’, Rhodium Group, 21 October 2022.

5. Fishman, E., Chokepoints: American power in the age of economic warfare, Penguin Random House, 2025.

6. Teer, J., ‘Semiconductors: European views on four 2029 tech transfer regime scenarios’, Policy Paper, Chips Diplomacy Support Initiative (CHIPDIPLO), September 2025, pp.30-31.

7. Ibid; ‘Three questions to Chris Miller: Navigating the geopolitics of semiconductors in a new Trump era’, Institut Montaigne, 7 May 2025.

8. Conversations with European semiconductor industry representatives and policymakers, May-June 2025, Brussels.

9. ‘Semiconductors: European views on four 2029 tech transfer regime scenarios’, op. cit., p.35.