Europe’s security and economic competitiveness are under growing strain. Danish intelligence estimates indicate that Russia could test NATO’s Article 5 in a few years time (1). Russia spends more than 8% of its GDP on defence, relies on a war economy, and its forces have been battle-hardened in Ukraine. Europe’s woes do not end there. China’s industrial overcapacity and supply chain weaponisation, Trump’s tariff threats, and persistently high energy prices undermine European industries.

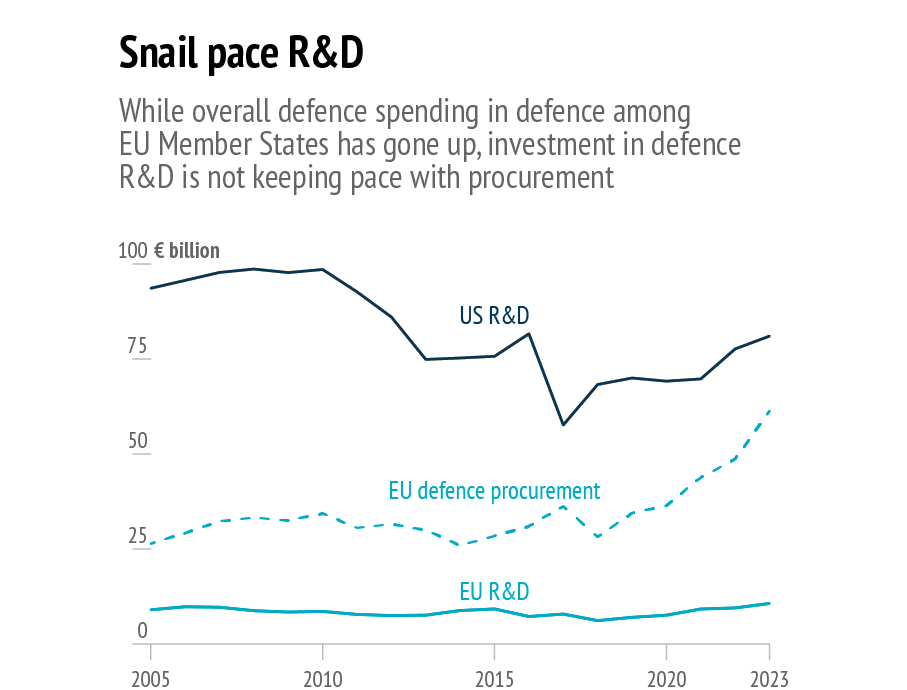

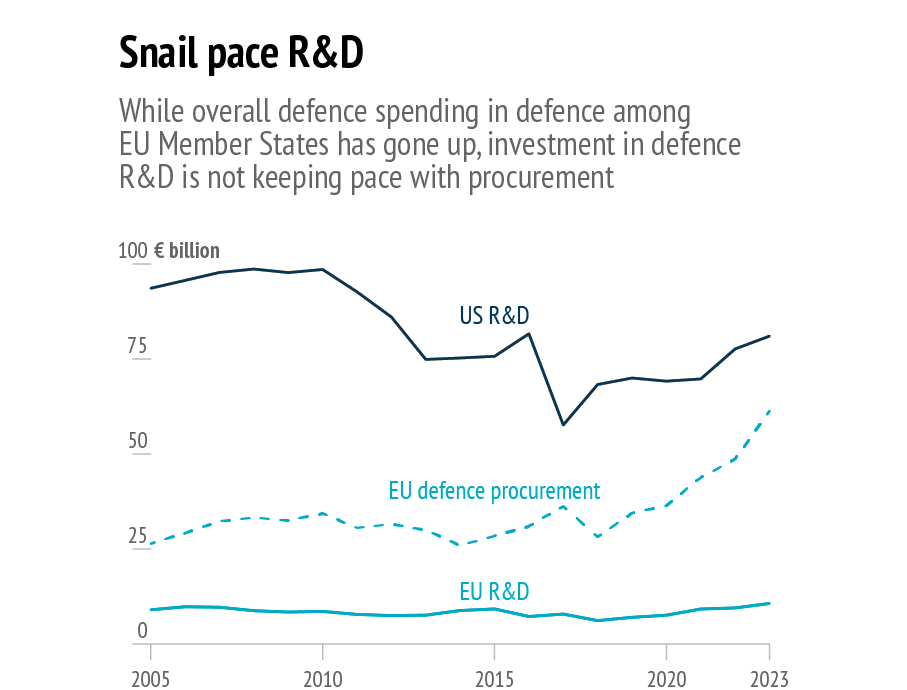

Right now, the stars are aligned to address the EU’s security and competitiveness crises with a new tool: increased defence budgets. With the Rearm Europe proposal and the NATO pledge to spend 5% of GDP on defence, EU Member States are set to dedicate substantial financial resources to strengthen deterrence. Governments should use these funds to invest in Europe’s long-term prosperity too. There is a mandate for this. NATO’s definition of defence spending already accounts for dual-use goods and R&D ‘when the military component can be specifically accounted for or estimated’ (2). The EU’s Political Guidelines highlight a global ‘fight for a technological edge […] and an increasingly thin line between economy and security’ (3). Both the EU and Member States can drive a dual-use Fourth Industrial Revolution tech boom, supporting the scaling-up of new companies.

A double dividend

At first sight, the predicaments of the US during the early Cold War in Europe, China in the post-Cold War period, and Ukraine following Russia’s invasion seem incomparable. After all, these states are vastly different in their geography, political systems and economic development. Yet, faced with an adversary with greater manpower, materiel, financial resources, or production capacity, they all turned to publicly funded dual-use innovation to tilt the military balance in their favour. Their investments kickstarted new commercial industries – inadvertently or by design. They enabled nascent but promising companies to overcome the ‘valley of death’ – the critical early stage of development when private financiers often deem such ventures too risky to fund.

In the early Cold War, the Warsaw Pact appeared to have a conventional advantage in Europe, fielding far more divisions than NATO. US policymakers questioned America’s military-technological edge: the USSR had launched the Sputnik satellite in 1957, and sent the first man into space soon after. To counter the Soviet Union’s military superiority, the US invested in disruptive technologies. Producing chips for the Apollo spacecraft’s guidance computer led Fairchild Semiconductor’s revenue to increase fortyfold. The US Air Force’s decision to use Texas Instruments’ integrated circuits for its Minuteman Missiles, ‘designed to hurl nuclear warheads through space before striking the Soviet Union’, led to a similar surge in sales (4).

Defence spending laid the foundation for America’s ‘precision warfare revolution’ and IT-dominance. The US semiconductor ecosystem went on to push the pace of innovation, and therefore the development of sensors, communication technologies and satellites. Washington’s subsequent dominance in long-range strike capabilities strengthened both nuclear and conventional deterrence in Europe and the ability to project power globally, epitomised by the US low-cost military victory in the Gulf War (5). These advances also delivered significant economic benefits, enabling the mass production of PCs, mobile phones, smartphones, gaming consoles and pacemakers.

In turn, these consumer markets sparked the development of increasingly powerful semiconductors. 60 years after securing a ‘first-mover advantage’ in the early Cold War era, the US still leads in semiconductor design. Its dominance has been sustained by abundant risk capital and the ability to attract top global talent to its research institutes and companies – helping it to hold onto key strengths in semiconductors ever since. For example, even today Pentagon programmes such as Project Maven, which aims to integrate AI into the armed forces, indirectly rely on Nvidia’s world-leading AI-chips. Meanwhile, Washington’s export controls deny strategic rivals access to these critical technologies.

To solve a similar conundrum, China directed large-scale public investment towards the development of military and dual-use technologies. In the 1990s, the US thwarted Beijing’s attempts to intimidate Taiwan by deploying Carrier Strike Groups during the Third Taiwan Straits crisis. Beijing’s strategy to turn the tables on the US at the peak of its relative power had high-tech at its core: mass production of cheap but highly precise missiles. These ‘carrier-killers’ prevent the US Navy from operating securely near China’s coastline. More recently, Beijing has reinforced these denial capabilities with swarms of even cheaper subsea, surface, and aerial attack drones.

Through its ‘Made in China 2025’ strategy, an ambitious industrial policy launched in 2015, China has strengthened its capacity to independently produce semiconductors, batteries and other dual-use components. Its companies have captured a world-leading 24% market in semiconductor manufacturing, even though they still lag behind Taiwan and Korea in manufacturing the most advanced chips (6). Chinese companies lead in advanced batteries, which provide drones with enhanced speed, range and stealth capabilities. This has delivered clear economic benefits: batteries are the cornerstone of China’s electric vehicle production, accounting for almost 60% of worldwide sales in 2023 (7). DJI, a drone and AI company, controls over 90% of the global consumer drone market as of June 2024 (8).

The goal of ‘Made in China 2025’ was to strengthen both national prosperity and security. China’s State Council declared that ‘building an internationally competitive manufacturing industry is the only way China can enhance its comprehensive national strength, ensure national security, and build itself into a world power’ (9). ‘Made in China 2025’ achieved many of its aims, including through mass subsidies for technology development, local content requirements, and regulatory barriers that limited foreign firms’ access to China’s domestic market (10).

States can even unlock disruptive military-civil innovation during wartime, as Ukraine’s post-2022 development of a thriving defence startup environment shows. Kyiv, facing an adversary with greater manpower and a high tolerance for losses, developed local solutions to counter Moscow’s advantages. Ukraine funded numerous start-ups to develop drones, artificial intelligence and other digital technologies.

This has been transformative. 500 domestic companies today support Ukraine’s drone production, collectively supplying 96% of the Ukrainian Armed Forces’ demand for unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). This has a direct impact on the battlefield: 60-70% of Russian losses in 2024 can be attributed to drones. Moreover, Ukraine’s unmanned fleet chased the Russian Navy out of the Western Black Sea, and inflicted damage on Russia’s strategic bomber fleet. Ukraine’s defence companies are developing machine learning software tailored to specific operational needs, such as offensive drone operations or air defence. Ukraine’s innovation cycle is extraordinarily short: labs and production plants rapidly upgrade weapons systems after receiving feedback on their battlefield performance (11).

Ukraine’s innovation ecosystem will likely yield benefits beyond the military realm. Its drone manufacturers are well-positioned to capture market share from Chinese producers of commercial drones for civilian use, such as helping firefighters control forest fires and police departments to track down criminals. Drone use can also transform delivery, transport, and logistics. The AI platforms developed during the war, such as Delta and Avengers, can be used for purposes such as border control and environmental monitoring.

A dual-use tech boom

Today’s emerging and disruptive technologies (EDTs) will generate security and prosperity benefits too. Some will pay off soon, for example cybersecurity products. Others, such as robotics and quantum, may revolutionise warfare and commerce throughout the next decades. Allowing Europe’s rivals to take the lead increases security vulnerabilities and risks further eroding the EU’s global competitiveness. Consider the following examples:

- To maintain deterrence, Europe needs to ensure that adversaries do not launch a debilitating first strike against its critical infrastructure, including its command-and-control (C2) systems. Given the scale of China’s cyber espionage activities, advanced cybersecurity products are essential to safeguard the EU’s security and its economic prosperity. European firms stand to benefit, as Europeans are rethinking their reliance on US technologies (12).

- Robots, like drones, can monitor critical infrastructure in extreme or inaccessible environments, like the deep sea. They can improve battlefield intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR), an area in which Europe remains highly dependent on the US. Robots can also maintain Europe’s manufacturing sector, by compensating for Europe’s ageing workforce.

- If rivals win the quantum race, they could decrypt military and other sensitive communications; whereas European leadership would strengthen encryption and revolutionise industries.

How can Europe make mass dual-use investment a success? Individual European Member States will likely take the lead in spurring innovation, through national initiatives such as SPRIN-D Germany’s agency for disruptive innovation, and the Netherland’s National Growth Fund for knowledge development, research and innovation. However, technology development will have to compete with the immediate priority to strengthen deterrence This includes defence spending with low economic returns, such as on ammunition production, personnel, and operations.

The EU can facilitate a dual-use tech boom. It has instruments at its disposal to support R&D with both civil and military uses, including:

- The European Innovation Council (EIC) is Europe’s flagship innovation programme to identify, develop and scale up breakthrough technologies. The EIC Transition Scheme provides follow-up support to translate research outcomes into viable commercial applications. The EIC will soon invest in dual-use technologies too.

- The EU Defence Innovation Scheme (EUDIS), funded by the European Defence Fund and worth €2 billion in 2025, aims to foster innovation in defence-specific technologies. It also aims to lower barriers for smaller players and innovators seeking to enter the defence sector.

- The Hub for EU Defence Innovation (HEDI) was established within the European Defence Agency (EDA) to promote military innovation. HEDI serves as a platform to facilitate cooperation on defence innovation among Member States, through identifying innovative ideas and supporting their implementation.

- The European Investment Bank (EIB) Group has recently updated the definition of dual-use goods and infrastructure eligible for financing, now excluding only purely military applications such as ammunition. Moreover, the EIB has expanded its lending capacity for SMEs working on defence innovation.

Conclusion

By building on these instruments, the EU and Member States can usher in a new era of dual-use innovation. They should be scaled up, simplified and integrated. While they provide valuable financing, they tend to fragment funding, entail excessive bureaucratic oversight, and create barriers and confusion for innovators seeking funding for applied dual-use research. (13) In contrast, the Draghi Report called for a ’European DARPA’, modelled after the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) that brings together the private sector, academia and industry to expand the frontiers of technology and science beyond immediate defence requirements (14).

To succeed, these initiatives should adopt DARPA’s core principles, including independence, freedom to adapt to changing geopolitical contexts, and acceptance of risk. This is particularly relevant to develop next-generation technologies: it provides lessons and generates new ideas, enabling bigger breakthroughs.

Second, the EU should dedicate substantial parts of the Rearm Europe plan/Readiness 2030 to disruptive innovation. Expanding the EU’s definition of defence spending to align with NATO – as one Member State has already requested – enables more dual-use investment to fall within the remit of Rearm Europe’s national escape clause (15). By encouraging countries to co-develop new technologies through SAFE loans or similar instruments, the EU would further strengthen links between innovation and defence ecosystems.

Finally, the EU should facilitate the inflow of talent and capital from partner countries. It should create incentives for talented researchers, whether from the US, India or elsewhere, to carry out applied research and work in high-tech industries in the EU. This should include encouraging Member States to ease visa restrictions to attract top international talent. European capitals should be ready to leverage defence budgets to support start-ups through the uncertain early stages of development, using public-private financing schemes. Initiatives like the Defence Omnibus are essential to reduce regulatory barriers and create a productive environment for technology development.

References

- 1 Jochecová, K., ‘Russia could start a major war in Europe within 5 years, Danish intelligence warns’, Politico, 11 February 2025 (https://www.politico.eu/article/russia-war-threat-europe-within-5-years-danish-intelligence-ddis-warns/).

- 2 NATO, ‘Defence expenditures and NATO’s 2% guideline’, 3 April 2025 (https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_49198.htm).

- 3 von der Leyen, U., Europe’s Choice: Political Guidelines for the Next European Commission 2024-2029, 2024, pp.26, 27 (https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/e6cd4328-673c-4e7a-8683-f63ffb2cf648_en?filename=Political%20Guidelines%202024-2029_EN.pdf).

- 4 Miller, C., Chip War: The fight for the world’s most critical technology, Simon & Schuster, 2023, pp.19, 20, 21

- 5 Krepinevich, A., The Origins of Victory: How disruptive military innovation determines the fates of great powers, Yale University Press, 2023, p.407.

- 6 Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) & Boston Consulting Group (BCG), Emerging Resilience in the Semiconductor Supply Chain, May 2024 (https://www.bcg.com/publications/2024/emerging-resilience-in-semiconductor-supply-chain).

- 7 International Energy Agency (IEA), ’Trends in electric cars’, 2024 (https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024/trends-in-electric-cars).

- 8 Yang, Z., ’Why China’s dominance in commercial drones has become a global security matter’, June 2024 (https://www.technologyreview.com/2024/06/26/1094249/china-commercial-drone-dji-security/).

- 9 PRC State Council, Notice of the State Council on the Publication of ‘Made in China 2025’, 2015, p.2 (https://cset.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/t0432_made_in_china_2025_EN.pdf).

- 10 MERICS, ’Beyond overcapacity: Chinese-style modernization and the clash of economic models’, April 2025, p. 7 (https://merics.org/en/report/beyond-overcapacity-chinese-style-modernization-and-clash-economic-models).

- 11 Bondar, K., ‘Ukraine’s future vision and current capabilities for waging AI-enabled autonomous warfare’, CSIS, 6 March 2025 (https://www.csis.org/analysis/ukraines-future-vision-and-current-capabilities-waging-ai-enabled-autonomous-warfare); Watling, J. and Reynolds, N., ‘Tactical developments during the third year of the Russo–Ukrainian War’, RUSI Report, 11 February 2025 (https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/special-resources/tactical-developments-during-third-year-russo-ukrainian-war).

- 12 Desmarais, A., ‘A threat to autonomy’, EuroNews, 20 March 2025 (https://www.euronews.com/next/2025/03/20/a-threat-to-autonomy-dutch-parliament-urges-government-to-move-away-from-us-cloud-services)

- 13 European Commission, ‘White Paper on options for enhancing support for research and development involving technologies with dual-use potential’, 24 January 2024 (https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2024-01/ec_rtd_white-paper-dual-use-potential.pdf); ASD, ‘ASD response to EU White Paper on technologies with dual-use potential’, April 2024 (https://www.asd-europe.org/news-media/publications/asd-position-papers/asd-response-to-eu-white-paper-on-technologies-with-dual-use-potential/); LERU, ‘Statement: Options for enhancing support for research and development involving technologies with dual use potential’ (https://www.leru.org/files/Publications/Dual-use-Funding_LERU-Statement.pdf).

- 14 ‘A growing number of governments hope to clone America’s DARPA’, The Economist, 3 June 2021 (https://www.economist.com/science-and-technology/2021/06/03/a-growing-number-of-governments-hope-to-clone-americas-darpa).

- 15 Faggionato, G. and Lunday, C., ‘Germany triggers EU’s emergency clause for defense spending’, Politico, 28 April 2025 (https://www.politico.eu/article/germany-jorg-kukies-eu-emergency-clause-defense-spending/).