Summary

- Europe’s prosperity relies on maritime routes extending into the Western Indian Ocean. Chokepoints such as the Strait of Hormuz and Bab el-Mandeb, along with key transit corridors like the Mozambique Channel, underpin its economic lifelines and global connectivity.

- Despite naval patrols, development programmes, and diplomatic engagement, Europe’s presence in the region remains diffuse. Regional structures such as the Djibouti Code of Conduct suffer from uneven policy implementation across countries, littoral states face capacity constraints, and competition among external and regional actors in the Horn and the Gulf exacerbates fragmentation.

- Effective maritime governance in the Western Indian Ocean requires aligning vision, cooperation and resources. The EU should leverage its comparative strengths: promoting the rule of law, enhancing capacity building, and fostering practical coordination among partners.

Europe’s prosperity depends on maritime routes that extend far beyond its shores, including the Western Indian Ocean (WIO), a central maritime corridor linking Gulf energy supplies, Asian manufacturing chains, and the subsea data routes connecting Africa, Asia and Europe. More than 15 major subsea cable systems transit the WIO, while around 30% of global container traffic transits the Red Sea, and some 20 million barrels of oil per day move through the Strait of Hormuz(1). This creates a structural dependency on the stability of WIO sea lanes: disruptions quickly translate into higher shipping costs, delays, and energy price volatility.

Yet maritime governance across the WIO varies significantly, producing a system that is functional but fragile. Coordination mechanisms exist, but their implementation is uneven and often contingent on external support. This Brief argues that effective maritime governance depends on the alignment of three elements: vision, cooperation, and resources. Vision refers to shared priorities; cooperation to the mechanisms and political will required to act collectively; and resources to the structural capacity to implement decisions. Where these diverge, stability rests on short-term crisis management rather than sustained security provision. The EU could focus on supporting the alignment of these elements over time.

Crowded waters

The WIO forms part of a single maritime system linking Asia to Africa and the Middle East. At the WIO’s eastern end, the littoral states of Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand developed mechanisms such as the Malacca Straits Patrol and the coordinated aerial surveillance initiative Eyes-in-the-Sky(2) which for a time created more predictable coordination routines in the Malacca and Singapore Straits. This model illustrates what alignment of vision, cooperation and resources can enable. Yet it is not directly transferable to the WIO, which features a larger and more contested maritime space and a higher concentration of actors competing for influence. The region’s diverse political and security conditions create uneven incentives for cooperation, making collective action harder to sustain.

Across the western WIO, littoral states confront a wide range of illicit maritime activity but differ in their capacity to respond to challenges like piracy, armed robbery at sea, migrant smuggling, and maritime terrorism. The eastern African littoral has become a key transshipment hub for narcotics and small arms over the past decade, with revenues estimated at around €165 million annually(3). Terrorist groups such as Al-Shabaab, which finance parts of their operations through smuggling networks, have been implicated in these flows(4). These revenue streams reinforce the economic incentives sustaining illicit activity and are difficult to address due to governance constraints on land, including fragile judicial frameworks and limited coastguard capability. The EU has provided substantial external support, including the EU-funded programmes MASE (€42 million) and CRIMARIO II (€17.5 million) which have sought to address some of these gaps (5). However capacity gains remain uneven, leaving enforcement more reactive than preventive.

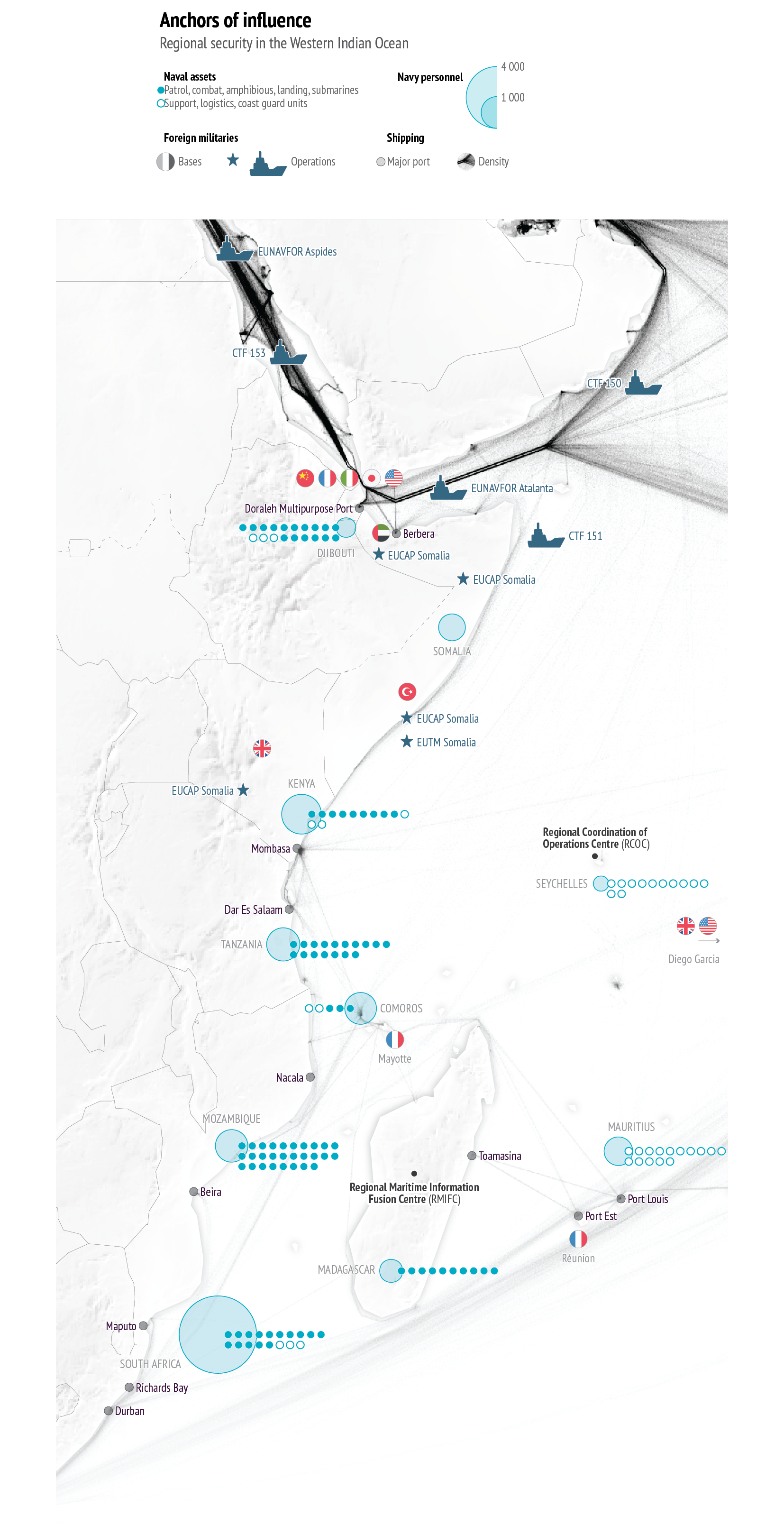

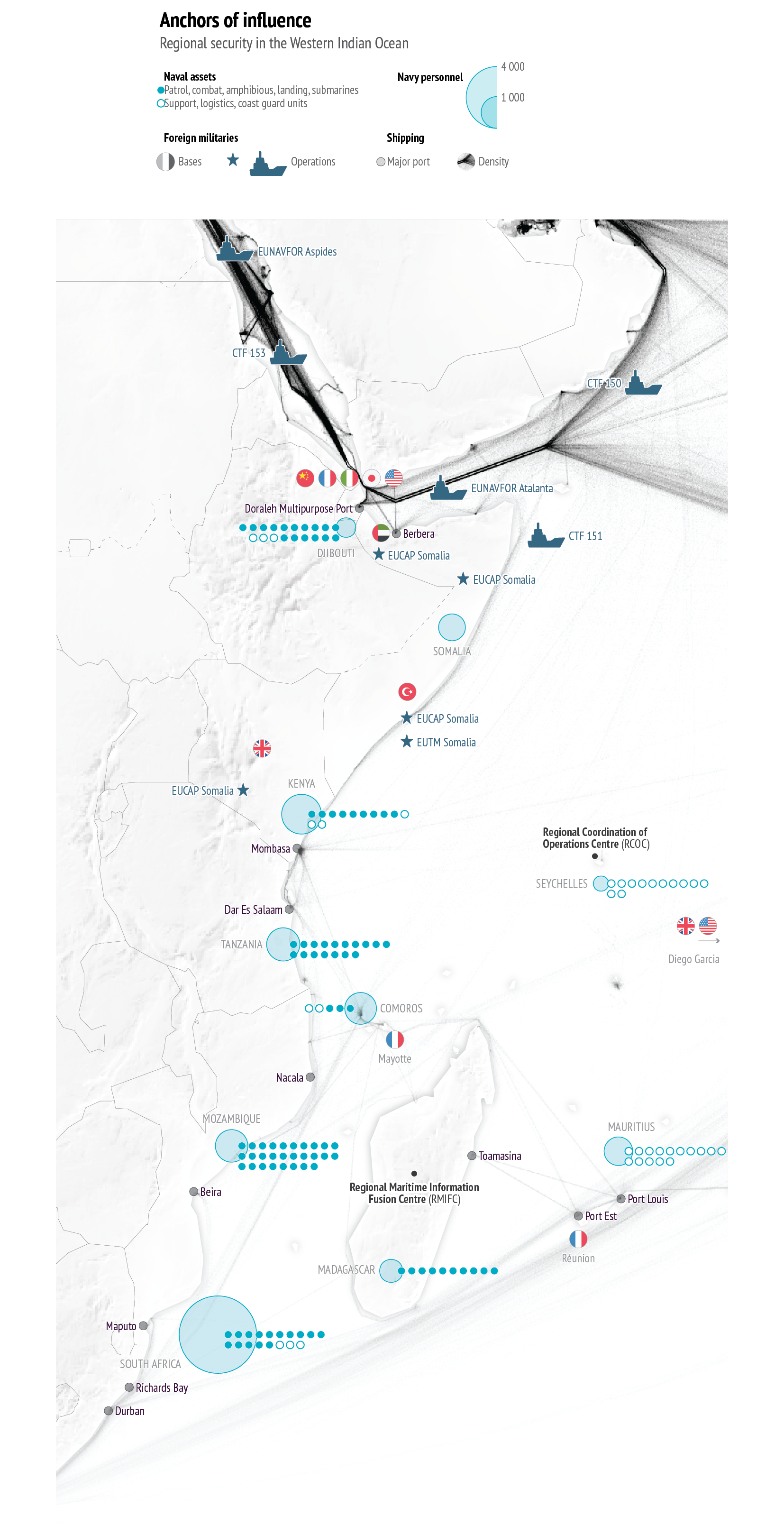

Given the region’s complexity, there is little incentive for cooperation, with many key actors pursuing interest-based strategies rather than alignment. India maintains multi-vector partnerships to preserve its ‘strategic autonomy’ – balancing cooperation with France, the US and others while maintaining ties with Russia. Gulf states, particularly the UAE and Saudi Arabia, have expanded port and logistics investments, often in competition(6). China has consolidated access through dual-use port infrastructure and financing arrangements across the African eastern littoral(7). Europe contributes through naval deployments (Atalanta, Aspides), the Coordinated Maritime Presence framework, and capacity-building missions (EUCAP and EUTM Somalia). Yet this involvement remains diffuse and often overstretched.

The limited coordination among external powers creates diverging priorities. This is reinforced on land through an accumulation of access, basing and training arrangements. Djibouti now hosts the region’s highest concentration of foreign military facilities, including the US, China, France, Italy and Japan. Somalia hosts a Turkish training and military base. Further south, France maintains permanent forces in La Réunion and Mayotte. The result is a cycle in which self-interest sustains presence but fails to generate incentives for shared governance.

A dense landscape of regional and sub-regional organisations has emerged to address maritime insecurity. The Djibouti Code of Conduct and its Jeddah Amendment link Red Sea and WIO states in countering maritime crime. Continental and regional strategies under the African Union, the Southern African Development Community, and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development emphasise maritime security as a foundation for resilient blue-economy development(8). The Indian Ocean Commission (IOC) has assumed a more operational role through EU-supported mechanisms like the Regional Coordination Operations Centre (RCOC) in Seychelles and the Regional Maritime Information Fusion Centre (RMIFC) in Madagascar which enhance maritime situational awareness and cross-border coordination.

External support has also strengthened information-sharing, patrol coordination, and training. EU initiatives such as the Coordinated Maritime Presence, CRIMARIO II, and the IORIS platform have improved maritime domain awareness; bilateral training missions, UN programmes, and port security investments add further layers of engagement. Yet providers’ interests shape these efforts, often prioritising access over long-term institutional consolidation. They are also tied to funding cycles, which limits continuity.

The result is a system where coordination becomes an end in itself rather than the product of shared political commitment. Overlapping mandates and competing priorities fragment already scarce resources, while unresolved regional rivalries undermine trust. Rivalries in the Horn of Africa divert diplomatic attention that could otherwise strengthen Red Sea cooperation, while differing Gulf state relationships with Mogadishu and Somaliland have created parallel rather than unified maritime enforcement efforts along the Somali coast(9). The outcome is cooperation that is reactive and transactional, constrained by limited resources.

Data: IISS, Military Balance, 2025; shipshub.com, 2025; DMDC, 2025; Combined Maritime Forces, 2025; IMF, Portwatch, 2025; European Commission, GISCO, 2025

Uneven shores

Differences in the alignment of vision, cooperation and resources across the WIO produce distinct governance patterns along the littoral. In the northern WIO, particularly around the Straits of Hormuz and Bab el-Mandeb, strategic competition and political mistrust constrain cooperative governance, even amid a dense security presence. In the southern WIO, around the Mozambique Channel, there is clearer alignment on maritime priorities, but limited sustained resources to act on them. These cases are illustrative rather than comprehensive; they highlight how differences in vision, cooperation and resources translate into different maritime security dynamics.

The Bad el-Mandeb is a critical transit corridor linking the Red Sea to the wider Indian Ocean. A wide range of naval deployments contribute to maritime security, including EU operations, combined task forces, and additional regional contributions. External economic engagement has also expanded, including about €515 million in Chinese investment in Djibouti’s port infrastructure and some €2.1 billion in UAE port facilities across Djibouti and Somalia(10).

Yet these engagements are driven by distinct national priorities rather than a vision of shared governance. The Saudi-led Red Sea Council has tried to support maritime security coordination across its members but has struggled to overcome regional divisions. Domestic capacities among littoral states also vary sharply. Somalia’s coastguard development is heavily reliant on external support, including EU training and funding(11). Yet renewed piracy incidents since 2024 highlight how fragile enforcement remains without effective judicial and inter-agency capacity onshore. Yemen’s ongoing conflict has fractured coastal authority, creating havens for illicit trafficking. Djibouti’s dense concentration of foreign bases reflects an order sustained by external deterrence rather than regional ownership.

The Mozambique Channel links East Africa to the Indian Ocean islands and hosts significant energy, fisheries and undersea data infrastructure(12). Littoral states express clear priorities for maritime security and blue-economy development and regional frameworks support coordination. The EU’s Safe Seas Africa initiative launched with the IOC in 2025(13) aims to institutionalise operational cooperation, while France provides continuity through its naval presence in the region, and India’s 2023 agreement with the RCOC(14) extends information networks eastwards.

However, operational resources remain uneven. Vessel patrols are frequently constrained by fuel shortages, maintenance challenges and personnel turnover. South Africa’s Operation Copper, repeatedly suspended due to budgetary pressures, exemplifies the wider challenge: no deployments were conducted between 2022 and 2024 because ‘most naval platforms were undergoing maintenance and repair’, and the Navy only achieved 2 641 hours at sea in 2023/24 against a planned 8 000(15). Such cases highlight how resource constraints limit sustained maritime presence even where cooperation frameworks exist. Their effectiveness depends on predictable and long-term funding which is not always guaranteed. The result is a system where priorities are broadly aligned but implementation fluctuates with resource availability.

Europe’s Role

Stability in the WIO depends on fragile arrangements that require steady reinforcement. Europe’s role is to support the durability of these mechanisms, not to shape the region’s security architecture.

Prioritise rule of law to address maritime insecurity at its source: Maritime security depends on justice systems ashore as much as on naval enforcement. Counter-piracy, anti-trafficking, and fisheries efforts are short-lived without credible prosecutions and accountability. Operations at sea require credible prosecution pathways on land. Strengthening judicial capacity, inter-agency coordination and investigative integrity is critical, but a lengthy and politically sensitive process.

Develop sustainable partner capacity through whole-of-life support: Maritime capacity development should move beyond asset provision. Support through the European Peace Facility and related instruments should prioritise maintenance, spare parts, sustained training, cyber-secure port operations, and stable institutional budgets. Ensuring that coastguard and port authorities can operate vessels, communications systems, and surveillance networks consistently requires investment in the long-term operational ecosystem and is critical to severing the linkages between trafficking networks and terrorism financing.

Coordinate without adding more coordination: The WIO is already saturated with forums, task forces, and coordination platforms. The priority is not to create new ones, but to make the existing architecture work. This means aligning training standards and operational procedures, sharing maritime domain awareness tools, and grounding support in shared assessments rather than external programme logics. Understanding where interests genuinely align, and where they do not, is crucial to avoiding duplication and competition among external actors. In short: coherence matters more than adding new initiatives.

References

* The authors would like to thank Irène Dubois, Luca Guglielminotti and Laura Remy, EUISS trainees, for their research assistance.

1 See: TeleGeography, ‘Submarine Cable Map’, 2025; JPMorgan Global Research, ‘What are the impacts of the Red Sea shipping crisis?’, 8 February 2024; US Energy Information Administration, ‘Amid regional conflict, the Strait of Hormuz remains critical oil chokepoint’, 16 June 2024.

2 ASEAN, ‘ASEAN Maritime Outlook’, August 2023.

3 Baruah, D. M., Labh, N. and Greely, J., ‘Mapping the Indian Ocean Region’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 15 June 2023.

4 Bueger, C., Edmunds, T., and Stockbruegger, J., ‘Securing the seas: A roadmap for enhancing UN maritime security governance’, UNIDIR, 2024.

5 Indian Ocean Commission, Maritime Security (#MASE Programme) Project Description, 2021; Expertise France, ‘CRIMARIO II–Critical Maritime Routes in the Indian Ocean’, 15 July 2025.

6 Salacanin, S., ‘Saudi Arabia and the UAE compete to be hubs for regional business’, Stimson Center, 24 January 2025.

7 Nantulya, P., ‘Mapping China’s strategic port development in Africa’, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 10 March 2025.

8 African Union, 2050: Africa’s Integrated Maritime Strategy (AIMS), 2012; SADC, ‘SADC Ministerial Committee of the Organ commits to bolstering peace and security in the region’, 19 July 2022.

9 Čok, C., ‘React, rinse, repeat: How Europe can help break Somalia’s cycle of conflict’, ECFR, 2 May 2025.

10 Blanchard, L.P., ‘China’s engagement in Djibouti’, CRS, 6 June 2025; Mosley, J., et al., ‘Turkey and the Gulf States in the Horn of Africa’, Rift Valley Institute, 2021.

11 EEAS, ‘European Union and the Federal Republic of Somalia’, 2024.

12 Mozambique LNG, ‘About the Mozambique Liquefied Natural Gas Project’, 2025.

13 Ministry of Internal Affairs Seychelles, ‘EU and the IOC sign agreement to implement the Safe Seas Africa (SSA) programme’, 8 May 2025.

14 Dryad Global, ‘Seychelles and India sign agreement on information sharing in maritime security’, 2024.

15 Heitman, H., ‘Ramaphosa extends Operation Copper maritime security deployment’, DefenceWeb, 3 April 2025.