The Gulf of Guinea (GoG) spans over 6 000 km of coastline and 19 states. The region is rich in natural resources: it holds significant reserves of gas (2.7% of total world reserves) and oil (4.5%), as well as other valuable minerals including diamonds, tin, bauxite, manganese and cobalt.

While the piracy threat in the region appears to be waning, other illicit activities are thriving. Its geographical location makes it an ideal gateway for illegal trafficking towards Africa and Europe, including narcotics from Latin America. Illegal, unreported and undocumented (IUU) fishing threatens local livelihoods and fish stocks in a region that accounts for 4% of global fish production (1).

While piracy and armed robbery incidents dropped by roughly 90% in 2024, compared to a peak in 2020 (2), weak rule-of-law and justice systems, coupled with the ongoing threats posed by IUU fishing and trafficking, continue to undermine security efforts.

As the region faces a fast-evolving security situation both inland and offshore and becomes a hotspot for global competition, this Brief presents three potential scenarios for the Gulf of Guinea. It explores how the EU could adapt to safeguard its interests in this strategically important region.

Navigating maritime security threats

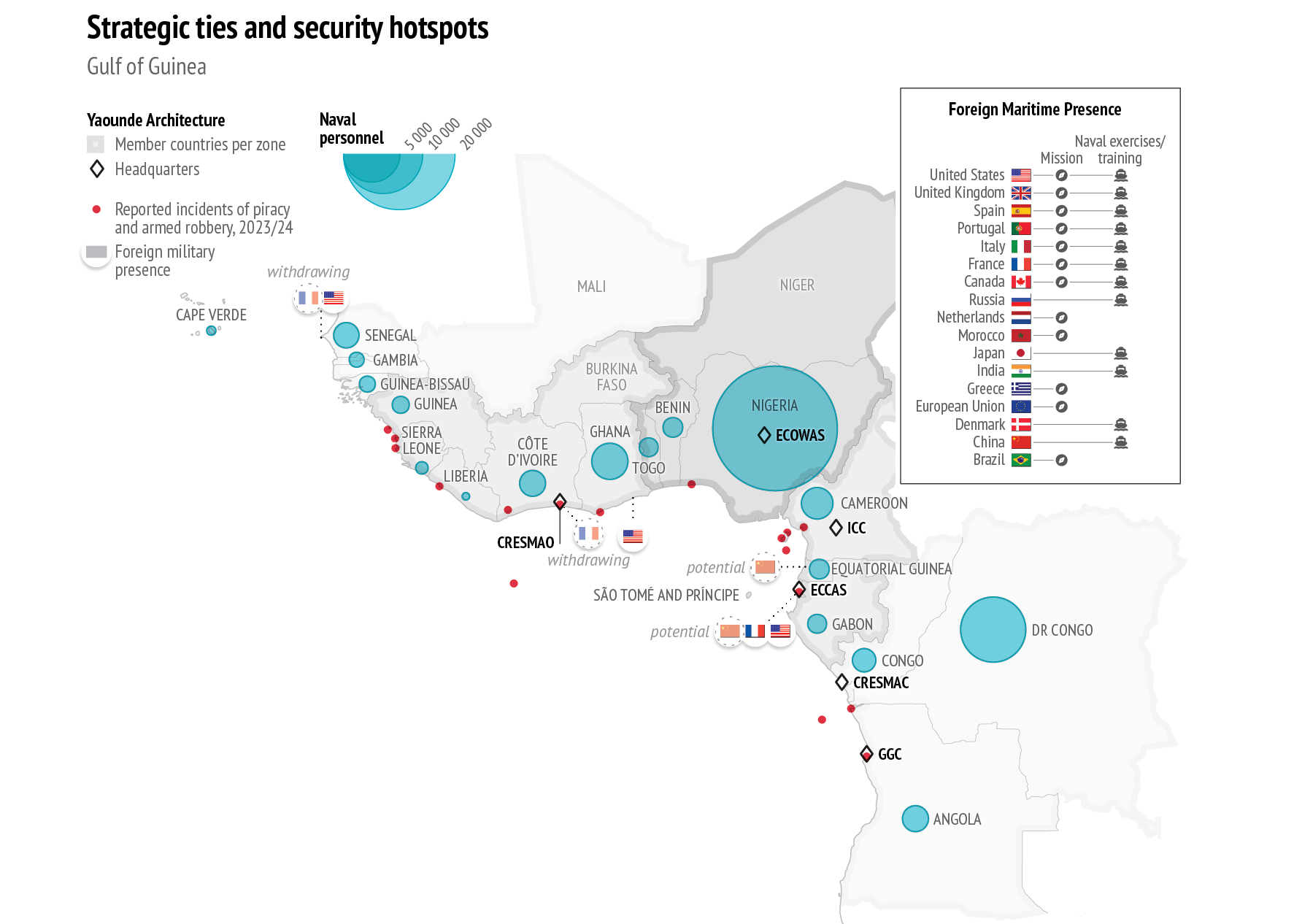

The Yaoundé architecture is the regional mechanism for maritime security that brings together countries in the Gulf of Guinea that are also members of the Economic Community of West Africa States (ECOWAS) and the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS). Established in 2013, it focuses on coordinating actions and developing legislation, enhancing patrol and coordination capacities among states, and combating piracy and armed robbery at sea in line with its code of conduct (3). The initiative unites regional countries and partners to improve security and navigation safety in the Gulf of Guinea through joint exercises, training, and capacity-building efforts.

Data: European Commission, GISCO, 2024; IISS, Military Balance, 2024; EU CMP, US Africom, UK Royal navy, Africa Center for Strategic studies, 2024 Acronyms: ECCAS (Economic Community of Central African States), GGC (Gulf of Guinea Commission) , ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States), CRESMAC (Regional Maritime Security Centre for Central Africa), ICC (Interregional Coordination Centre), CRESMAO (Regional Maritime Security Centre for West Africa).

Global navies, including those from India, Brazil, EU Member States, China and Russia, have expanded their presence in the region. While piracy incidents have declined due to increased patrols, challenges such as illegal fishing and various forms of trafficking persist, exploiting weaknesses in deterrence and enforcement mechanisms. Estimates indicate that IUU fishing may represent up to 40% or even 65% of total catches, while cocaine seizures in West Africa amounted to approximately 16 442 kg in 2022 (4).

Despite ongoing challenges in maritime capabilities for patrolling the extensive coastline, deterrence of piracy and armed robbery at sea is working. However, efforts to prosecute suspected criminals and integrate maritime security legislation into domestic legal frameworks have made limited progress (5). Trials of suspected pirates have proved particularly problematic, with only three cases tried in court – in Togo, Nigeria and Denmark – in the past decade, despite 115 piracy incidents reported in 2020 alone (6). The prosecution of criminals remains a significant challenge in the region, also for EU Member States that deploy navies there. There have been several instances where difficulties or outright refusals have arisen regarding the handover of suspects to national jurisdictions. While EU Member States are working to develop legal arrangements for the handing over of suspects, many countries in the region are either unwilling to pursue further prosecutions, fearing further strain on their legal systems, or lack the necessary legal framework to do so.

Increasing onshore security threats, such as terrorism in the northern regions of Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Togo and Nigeria, are putting additional pressure on their capacities and budgetary resources. With limited funds for public spending, these countries are forced to make tough decisions on whether to allocate resources to internal security forces and armies, navies and coastal guards, or their judicial systems.

Partners: cooperation, competition and co-existence

The EU has invested heavily in supporting regional partners, allocating more than €30 million through the European Peace Facility (EPF), as well as around €90 million for various maritime security and resource management projects. The EU’s Coordinated Maritime Presence (CMP), facilitated by a Maritime Areas of Interest Coordination Cell (MAICC) within the EU Military Staff, coordinates Member State deployments in the region.

Data: EnMar, 2024; EU Council; European Commission, GISCO, 2024

In addition to the EU, several other countries recognise the strategic importance of the Gulf of Guinea and are stepping up their involvement. China has established a strong presence in the region’s commercial ports and has ambitions to set up naval bases in Equatorial Guinea and Gabon. It also faces allegations of widespread IUU fishing by its vessels (7). Türkiye has made more limited investments in ports, while Russia contributes to training and exercises in the region and is reportedly exploiting Liberia’s vessel registration system for its own ships (8). India and Brazil have expanded their naval presence by supporting the Yaoundé architecture and participating in joint exercises, including with the EU. The US, the UK and France regularly conduct large-scale exercises, such as the Obangame Express and the Grand Africa NEMO. These exercises aim to train local navies and foster cooperation among regional and international fleets deployed in the Gulf of Guinea.

The EU has emerged as a key player in the Gulf of Guinea, adopting a comprehensive approach that links maritime security with economic development and inland security. It has demonstrated its commitment by the deployment in 2023 of the EU Security and Defence Initiative in Support of West African Countries of the Gulf of Guinea (EU-SDI-GoG) to support the fight against insecurity in the northern regions of Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Togo and Benin. However, long-term success will require a sustained focus on strengthening preventive mechanisms and judicial systems. Moreover, supporting local economies is crucial to avoid the exacerbation of grievances that could otherwise fuel recourse to criminal activities.

As some countries in the region head towards elections (Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire), others raise concerns about foreign military presence and fisheries agreements (Senegal). Meanwhile, ECOWAS is grappling with the withdrawal of the countries of the Central Sahel. In this context, the EU can and should enhance its strategies by continuing to link internal and maritime security. At the same time, it must be ready to adapt with contingency planning and differentiated approaches should the situation evolve. The EU should also focus on fostering cooperation, whenever possible, with countries like India and Brazil – not only for joint exercises but also for IUU fishing – and where necessary be prepared to compete, including in domains such as surveillance, secure communication and cybersecurity (9).

Drop anchor? Scenarios for the region

Balancing security challenges: In this most likely scenario, countries in the Gulf of Guinea will continue along the trajectory of balancing security challenges inland and offshore. While terrorism, domestic conflict, piracy and organised crime will persist, they are not expected to entail a significant increase in instability. Maritime security investments by countries in the region will remain low but, with international support, their capabilities will improve, and national legal systems will continue to transpose international and regional norms. In this scenario, the EU should maintain its support for regional frameworks, enhance coordination among Member States within the Coordinated Maritime Presence (CMP), and expand programmes that support economic development.

Cooperation with partners like the UK, the US, India and Brazil in areas such as cybersecurity, information sharing and local maritime domain awareness will be key to increasing maritime security, supporting local partners and countering the expansion of systemic rivals. In this context, to navigate geopolitical competition effectively, the EU should define a clear value proposition, demonstrating that its interests align with the economic growth aspirations of local partners. A focus on justice systems, basic services (education, health), and livelihoods can have a positive impact on countries in the region. However, the EU should also strengthen its control mechanisms to address potential IUU fishing by EU-flagged vessels, ensuring coherence with its broader objectives. At the technical and political levels, it should work with local partners to increase transparency in public registries, especially for fishing licences and vessel registrations. It should negotiate agreements for the transfer of criminal suspects to coastal states, and support reintegration programmes for former convicts. Civil society and local community involvement is essential to improve transparency as well as effective reporting mechanisms for suspected illegal activities.

Growing challenges: This worst-case scenario features further turmoil in the region, with additional ECOWAS or ECCAS member states experiencing a significant deterioration of their internal security situation. The weakening of internal security could pave the way for an expansion of terrorist and criminal groups, a surge in disinformation and foreign influence campaigns – mirroring the situation experienced in the Sahel. In this case, maritime security would be overshadowed by other security concerns and localised disruptions could impede the EU’s ability to take effective action.

In this scenario, the operational capacity of ports could become limited, thus disrupting maritime trade and complicating technical support and bunkering for vessels trading with the EU, especially those already taking longer routes around the Cape of Good Hope due to instability in the Red Sea. Security on the high seas may become reliant on international partners alone. Furthermore, countries like Türkiye, China and Russia may resort to private military companies to safeguard investments in infrastructures or mining, or to expand their influence. Therefore, the EU may need to reassess its strategies. Preparedness for worst-case scenarios implies that the EU and its Member States must prepare for the most adverse outcomes, even if they seem unlikely. This could involve anticipating specific conditions and sectors where engagement could still be pursued while maintaining unity. Priorities should include keeping diplomatic channels open, improving strategic communication and countering disinformation campaigns, along with investments in technologies that enable secure communications and navigation for EU-flagged vessels.

Advancing in tackling challenges: This best-case scenario envisions a positive trajectory for countries in the region. In this scenario, deterrence efforts in high seas and territorial waters remain effective, while coastal states embrace the Yaoundé architecture and code of conduct. Legal systems and capacities are strengthened, paving the way for self-reliance, improved port management, fleet expansion, and increased prosperity for riverine communities through public-private partnerships. While upcoming elections might lead to temporary contestation, they would ultimately maintain democratically elected governments. Overall, countries commit further to strengthening the rule of law and enhancing their capacity to tackle security challenges. In this scenario, the EU should focus on bolstering cooperation to improve port management, promote private investments to support local value chains, and advance capacity-building initiatives for security forces and the judiciary.

Conclusion

The EU’s support for regional and national maritime security in the Gulf of Guinea has the merit of fostering cooperation with EU Member States and with the navies of countries like the UK, the US, India and Brazil. It also effectively combines security efforts

both onshore and offshore with development initiatives. However, the EU should prepare for worsening scenarios in the region, as the region’s security dynamics grow more complex. The EU’s priorities should be to prevent escalation and to develop contingency plans for deteriorating security conditions, outlining actions to take – or avoid – in the event of further instability.

References

(1) Morcos, P., ‘A transatlantic approach to address growing maritime insecurity in the Gulf of Guinea’, CSIS, 1 February 2021 (https://tinyurl.com/4ynxth8p).

(2) United Nations Security Council, Report of the Secretary-General, ‘Situation of piracy and armed robbery at sea in the Gulf of Guinea and its underlying causes’, S/2022/818, 1 November 2022 (https://tinyurl.com/55e52kc7); International Maritime Bureau, IMB Piracy & Armed Robbery Map 2024 (https://icc-ccs.org/index.php/piracy-reporting-centre/livepiracy-map).

(3) IMO, ‘Maritime security in West and Central Africa’ (https://tinyurl.com/p4a5h8kw).

(4) Benson, J., The Risk of Maritime Radiological and Nuclear Trafficking By Small, Traditional, And Unregistered Vessels, Stable Seas Report, 30 March 2022 (https://tinyurl.com/2tvbkujp) and UNODC Data (https://dataunodc.un.org/dp-drug-seizures).

(5) Tisseron, A., ‘Lutte contre la piraterie dans le golfe de Guinée – L’architecture de Yaoundé : dix ans après, au milieu du gué’, Étude 104, IRSEM, March 2023 (https://www.irsem.fr/media/etude-irsem-104-tisseron-golfe-de-guin.pdf).

(6) Larsen, J., ‘What shall we do with the suspected pirates?’, DIIS Policy Brief, 30 March 2023 (https://tinyurl.com/yfu8y2nn).

(7) Paarlberg, R., ‘West Africa’s falling fish stocks: illegal Chinese trawlers, climate change and artisanal fishing fleets to blame’, The Conversation, 9 April 2024 (https://theconversation.com/west-africas-falling-fish-stocks-illegal-ch…).

(8) See: Geall, S. et al., Charting a Blue Future for Cooperation between West Africa and China on Sustainable Fisheries, Stimson Report, July 2023 (https://tinyurl.com/463hjx6z). The total deadweight tonnage of vessels flagged in Liberia skyrocketed from 217 million in 2017 to 378 in 2023 (+74%): see UNCTAD, ‘Merchant Fleet’, Handbook of Statistics 2023 (https://unctadstat.unctad.org/insights/theme/25).

(9) Tachie-Menson, E.A., ‘An in-depth analysis of maritime security in the Gulf of Guinea’, Accord Conflict Trends 2024/1, 5 September 2024 (https://tinyurl.com/yau5uhyd).