In early September 2024, the US Department of Justice announced a set of measures to curb electoral interference in the upcoming presidential election, scheduled to take place two months later (1). This was the most significant indication to date that foreign actors were seeking to meddle with the election. In a deeply polarised environment and with the outcome appearing to be on a knife’s edge, there was widespread concern that foreign powers could significantly disrupt the election and affect its result. In the end, Donald Trump’s resounding victory – and the swift acceptance of the result by the Democratic Party – dispelled those concerns. However, this should not serve as an excuse to overlook the significant attempts by foreign powers to influence the democratic process. Strategic rivals are becoming bolder and more astute in their information manipulation and other interference activities. US agencies implemented several measures to respond to these malign actions and prevent disruptions. To counter future interference, the EU should learn how US authorities and other stakeholders responded. This Brief outlines five lessons for Europe.

Foreign meddling in the run-up to the elections

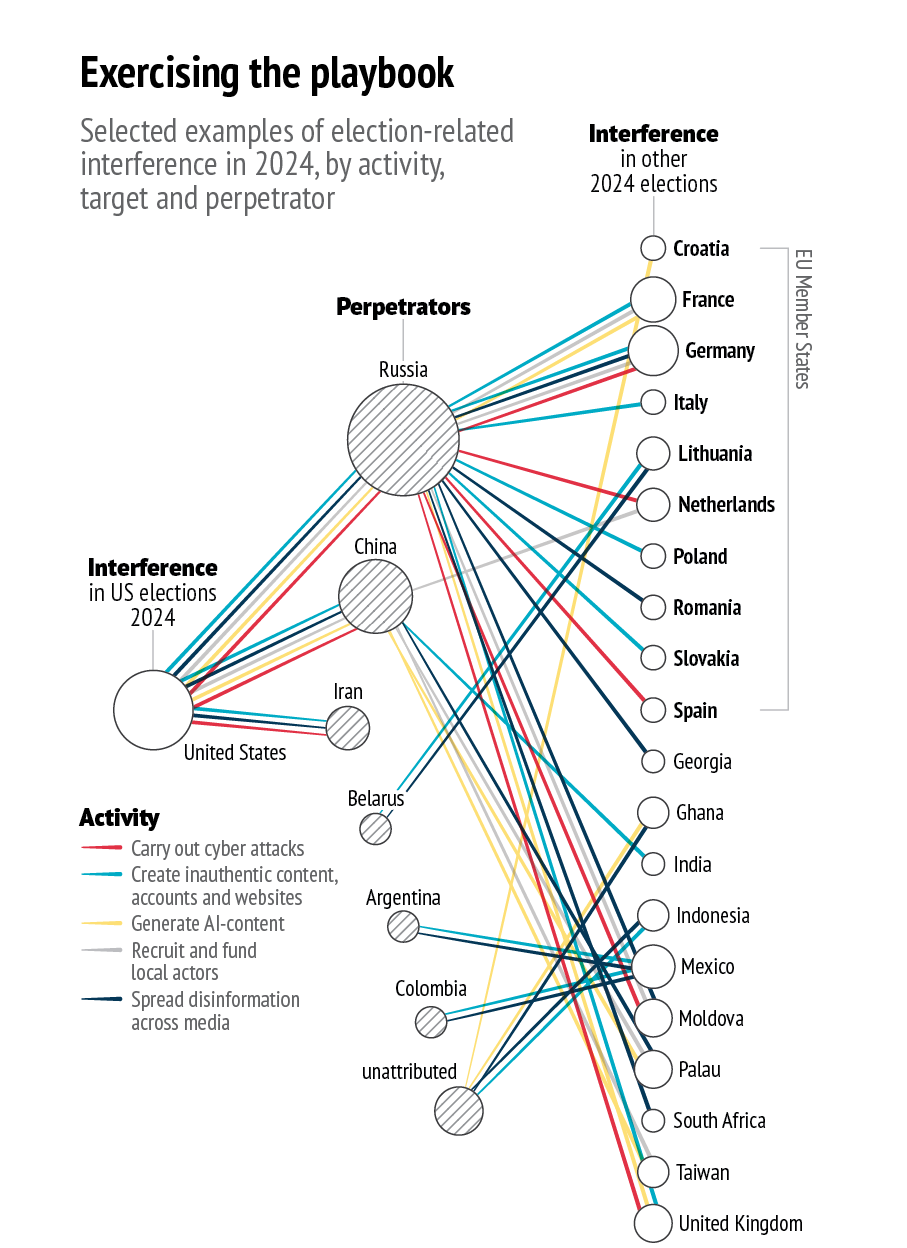

The US’s three main strategic adversaries – Russia, China and Iran – were all involved in efforts to influence the 2024 election. This was not their first attempt: Russia interfered in the 2016 election, while China and Iran were active in the 2022 midterms. In 2024, Russia appeared to favour Trump because of the now president-elect’s stance on the war in Ukraine and criticism of NATO. Iran, in contrast, was opposed to Trump’s return due to his past policy of maximum pressure against Tehran. China did not appear to show a preference for either candidate (2).

Data: EUISS research based on 3News, ABC, African Digital Democracy Observatory, Aljazeera, Atlantic Council, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Barron’s, Brookings, Die Zeit, EuroNews, EUvsDisinfo, FP, France24, GMF, ISD, Journal of Democracy, Microsoft, Modern Diplomacy, NBC News, Politico, Progressive International, Sur, The Guardian, Thomson Foundation, Usanas Foundation, Washington Post, 2024.

Beyond this, all three adversaries agreed on one objective: they wanted to sow chaos and undermine electoral integrity, while creating mistrust within the American electorate. A China-aligned influence operation had the apparent goal to ‘seed doubt and confusion among American voters’ (3). Another group, linked to Iran, also appeared to be ‘laying the groundwork to stoke division in the election’ (4).

These actors also extended their efforts across the Atlantic, aiming to erode trust in American democracy among European publics. An FBI dossier filed in a court affidavit in September included evidence of a Russian operation targeting politicians, businesspeople, journalists and other key figures in Germany, France, Italy and the UK. The messaging sought to undermine the transatlantic relationship, question support to Ukraine and depict the US as untrustworthy.

Back to the AI future

Russia, China and Iran all demonstrated a growing ability to create and disseminate AI-generated media and digital content during the 2024 campaign (5). In January, a fabricated video depicted President Biden urging New Hampshire voters to abstain from voting in the state’s Democratic primary. Similarly, following Biden’s withdrawal, a deepfake audio of Vice-President Harris appearing to speak incoherently circulated on TikTok. Fake audio clips of Trump mocking Republican voters were also spread. Beyond the US, over 130 deepfakes have been identified in elections worldwide since September 2023 (6).

Allying with local actors

Foreign actors relied on recruiting local influencers, activists, and even commercial companies ahead of the election. As usual, extremist groups used the Russian-owned platform Telegram to spread disinformation. Beyond Telegram, the FBI affidavit outlines Russia’s efforts to secretly fund and promote a network of right-wing influencers: ‘RT had funnelled nearly $10m to conservative US influencers through a local company to produce videos meant to influence the outcome of the US presidential election’ (7). RT employees also sought to hire a US company to produce Russia-friendly content. By outsourcing some of its efforts to commercial firms, Russia seeks to distance itself from the content created.

Fake it till you make it or break it

During the electoral campaign, foreign actors increasingly posed as American citizens. China was especially active in promoting ‘real videos, images and viral posts targeting US culture war issues, primarily from a right-wing perspective’ (8). Topics shared included LGBTQ+ issues, immigration, racism, guns, drugs and crime. The campaign aimed at ‘camouflaging’ China-friendly content as domestic discourse and used ‘spamouflage’ tactics to spread misleading information through inauthentic accounts. Iranian groups created fake websites, impersonating American activists and promoting divisive content.

A plethora of cyber threats

In August, Iran targeted the Trump campaign, stealing a lengthy vetting document on vice-presidential nominee JD Vance and distributing it to media outlets. Iran-linked accounts also sent threatening emails to escalate tensions: since 2022, Democrat-registered voters have received emails from alleged members of the Proud Boys organisation threatening them to ‘vote for Trump or else…’ In a campaign known as ‘Doppelgänger’ Russian hacktivists utilised a wide network of social media accounts to target public opinion. These accounts impersonated legitimate news websites to mislead and confuse, or to spread whistleblower information that had been ignored by the mainstream media. For instance, Russian influence network Stork-1516 promoted a fabricated video in which a teenage girl in a wheelchair claimed that she had been paralysed after a hit-and-run accident involving Harris.

Five lessons for the EU

In the end, the electoral result was not contested. Trump won decisively and Harris accepted the outcome. This swift adherence to the norms of democratic transition rendered any potential efforts by foreign states to sow uncertainty during the transition period effectively unfeasible.

However, much of the credit also goes to US authorities, who implemented a well-coordinated counter-interference strategy prior to and on election day. This was a whole-of-government approach, which included non-government agencies as well, and built on the lessons learned from previous elections. For instance, in 2016 the media released the Russia-hacked Hillary Clinton campaign emails to the public. That choice ultimately played into the hands of the cyberattackers, harming Clinton’s chances. This time around, news agencies refrained from publishing the Vance vetting documents.

It is impossible to know for sure whether these measures would have neutralised the impact of malign activities, especially if the electoral outcome had been less clearcut – for instance, with a more tightly contested electoral college result. Nevertheless, they were key in strengthening the resilience of the electoral process.

The EU should carefully analyse the US playbook for 2024. It contains some practices that the EU and Member States already follow, but also some innovative strategies. As our visual shows, many forms of interference seen in the US were also observed in elections in Europe and beyond. Brussels must be ready to protect democracy from future interference. Learning from the US elections – understanding what worked well and what could be improved – is a crucial first step towards safeguarding democracy.

Forewarning and resilience building in the information space: Ahead of election day, US authorities focused on increasing transparency and raising awareness about manipulative techniques used by foreign interferers. The Office of the Director of National Intelligence published public bulletins and regular security updates from 100 days to 15 days prior to the elections, a practice also known as ‘pre-bunking’. Such practices, which emphasise exposing interference incidents, are more effective when complemented by proactive strategic communications – such as pre-emptive information sharing with the wider public. This approach proved successful in the US, and the EU should implement a similar strategy. For instance, the EEAS could publish periodic public threat assessments ahead of elections (9).

Reinforced inter-institutional coordination: In 2022, the US established the Foreign Malign Influence Center (FMIC) to ‘mitigate threats to democracy and US national interests from foreign malign influence’ (10). The FMIC coordinated more than twenty agencies to safeguard the presidential elections (11). Through joint statements with the FBI and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), they exposed Russia‘s efforts to amplify inauthentic content and debunked false videos. CISA also worked closely with election officials to strengthen their defences against foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI) and physical threats. EU countries are adopting similar practices, such as Sweden (the Psychological Defense Agency) and France (Viginum).

Increased coordination between law enforcement agencies and the media to unveil indictments and expose Kremlin-led disinformation campaigns bolstered domestic preparedness. Finally, for the first time, the FBI operated a coordination hub collecting, assessing, sorting and sharing tips and information on potential interference threats. This established a ‘direct line between the FBI and election officials’ (12). Enhanced inter-institutional coordination between national authorities, intelligence services and election officials across the EU Member States could similarly improve situational awareness at the EU level.

Using both carrots and sticks: Drawing from the experience of 2020, law enforcement and election officials were ready for potential disputes over vote counting. Paper backups for ballots were prepared to counter any disruption to machine voting. Despite a couple of bomb threats and episodes of disinformation about fake ballots, polling stations operated without severe disruptions. A cross-sectoral approach helped counter more sophisticated covert operations. For instance, the Treasury Department was involved in tracking money flows to a small Nashville-based company, Tenet Media, which facilitated the spreading of Russia’s narratives, through Russian bot farms and pro-Russian domestic influencers. This eventually led to sanctions being imposed on the Russian contractors involved.

In addition to criminal charges, the authorities put in place a reward system to obtain information leading to the capture of actors involved in foreign interference activities. This contributed to the indictment of three cyber operatives from the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), among others (13).

Training against AI misuse: Deepfakes are increasingly being used for deception in numerous countries. The FMIC trained staff to swiftly detect and evaluate the authenticity of such material. Addressing AI misuse will require increased government resources and ongoing exercises throughout election cycles to keep pace with technological advancements. It also requires enhanced engagement with social media and technology companies, regulation of the algorithms enabling the amplification of harmful content, and greater accountability within the private sector. Such measures would further strengthen efforts to crack down on AI-driven information manipulation.

Keeping politics out of the fight: Based on the experience of 2016, journalists and analysts cautioned against the risk of spinning disinformation for partisan advantage. Ahead of the 2024 election, the US prepared a plan to ensure impartial intelligence sharing. Originally formulated in 2019, but signed off under Biden’s presidency, the formal protocol relies on assessments from a designated ‘expert group’ composed of intelligence analysts and civil servants from various agencies. They evaluate intelligence on foreign interference according to specific criteria, and decide whether to issue emergency notifications to the public. The number of recommendations for such notifications has increased threefold since 2020.

The EU and its Member States should consider a similar system to ensure that government alerts about malign interference remain free from political influence, with media from across the political spectrum equally engaged in communicating evidence to foster a common understanding.

References

* The authors would like to thank Lisa Hartmann González, EUISS trainee, for her invaluable research assistance.

- Barnes, J., Thrush, G. and Myers, S., ‘U.S. announces plan to counter Russian influence ahead of 2024 election’, The New York Times, 4 September 2024 (https://www.nytimes. com/2024/09/04/us/politics/russia-election influence. html); Affidavit retrieved from ‘FBI dossier reveals Putin’s secret psychological warfare in Europe’, Politico, 5 September 2024 (https://www.politico.eu/article/fbi-dossier-reveals-russian-psy-ops-disinformation-campaign-election- europe/).

- Thomas, E., ‘Pro-CPP ‘spamouflage’ network pivoting to focus on US presidential election’, Institute for Strategic Dialogue, 15 February 2024 (https://www.isdglobal.org/digital_dispatches/pro-ccp-spamouflage-net-work-focuses-on-us-election/); DiResta, R., ‘Iran hack illuminated long- standing trends- and raises new challenges’, Lawfare, 26 August 2024 (https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/iran-hack-illuminates-long-standing-trends-and-raises-new- challenges?ref=disinfodocket.com).

- Microsoft Threat Intelligence Report, ‘Russia, Iran, and China continue influence campaigns in final weeks before Election Day 2024’, 24 October 2024 (https://cdn-dynmedia-1. microsoft.com/is/content/microsoftcorp/microsoft/msc/ documents/presentations/CSR/MTAC-Election-Report-5-on- Russian-Influence.pdf).

- Ibid.

- Cooke, D. et al., ‘Crossing the deepfake rubicon’, CSIS, 1 November 2024 (https://www.csis.org/analysis/crossing- deepfake-rubicon).

- German Marshall Fund, ‘Spitting Images: Tracking deepfakes and generative AI in elections’, Interactive Tool, 2024 (https://www.gmfus.org/spitting-images-tracking-deepfakes-and- generative-ai-elections).

- ‘Meta bans Russian state media outlets over “foreign interference activity”’, The Guardian, 17 September 2024 (https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/sep/16/meta-bans-rt-russian-media-outlets).

- Nayak, D., ‘Election integrity & the cyber threat landscape of the 2024 U.S. election’, CyberProof, 30 October 2024 (https://www.cyberproof.com/blog/election-integrity-the-cyber- threat-landscape-of-the-2024-u-s-election/).

- The second report by the European External Action Service on FIMI threats outlines five types of incidents requiring threat assessment and preventive societal resilience building up to one year before the elections. EEAS, ‘2nd EEAS Report on Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference Threats’, January 2024 (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/ files/documents/2024/EEAS-2nd-Report%20on%20FIMI%20 Threats-January-2024_0.pdf).

- Office of the Director of National Intelligence, ‘Organization’ (https://www.dni.gov/index.php/nctc-who-we-are/ organization/340-about/organization/foreign-malign- influence-center).

- Kirkpatrick, D. D., ‘The US spies who sound the alarm about election interference’, The New Yorker, 21 October 2024 (https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2024/10/28/the-us-spies- who-sound-the-alarm-about-election-interference).

- Sikora, K., ‘Interference interrupted: The US Government’s strides defending against foreign threats to the 2024 election’, German Marshall Fund, Alliance for Securing Democracy, 21 November 2024 (https://securingdemocracy.gmfus.org/how- the-us-government-hit-back-at-foreign-interference-in- the-2024-election/).

- US Department of Justice, ‘Three IRGG cyber actors indicted for ‘hack-and-leak’ operation designed to influence the 2024 U.S. presidential election’, Office of Public Affairs, 27 September 2024 (https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/three-irgc-cyber-actors-indicted-hack-and-leak-operation-designed- influence-2024-us).