Summary

- The European cloud market is largely dominated by US providers, creating structural dependencies and posing risks to the confidentiality of European data.

- Conceived as a technical certification framework for cloud security, the European Cybersecurity Certification Scheme for Cloud Services (EUCS) has triggered wider debates on European digital sovereignty. Divergences among Member States have stalled the scheme’s adoption, delaying progress on other EU and national digital initiatives.

- The evolving geopolitical landscape, most notably Donald Trump’s re-election, is reshaping European priorities and could ultimately bring Member States’ positions on the EUCS closer together.

The governance of cloud infrastructure could prove a crucial test for Europe’s ability to act collectively and to define its digital ambitions. The plurality of domestic cloud standards in the EU has led to both market fragmentation and heightened risks to the security of European information and communication systems (ICS). The European Commission (EC) has thus tasked the European Cybersecurity Agency, ENISA, to develop and implement common European certification frameworks. However, what began as a technical initiative to harmonise cybersecurity standards for cloud services across the EU has evolved into a highly charged political debate that cuts to the heart of Europe’s digital sovereignty, and divides Member States. The main points of contention concern the stance to be taken vis-à-vis American service providers, who maintain a dominant position in this strategic sector.

The American oligopoly

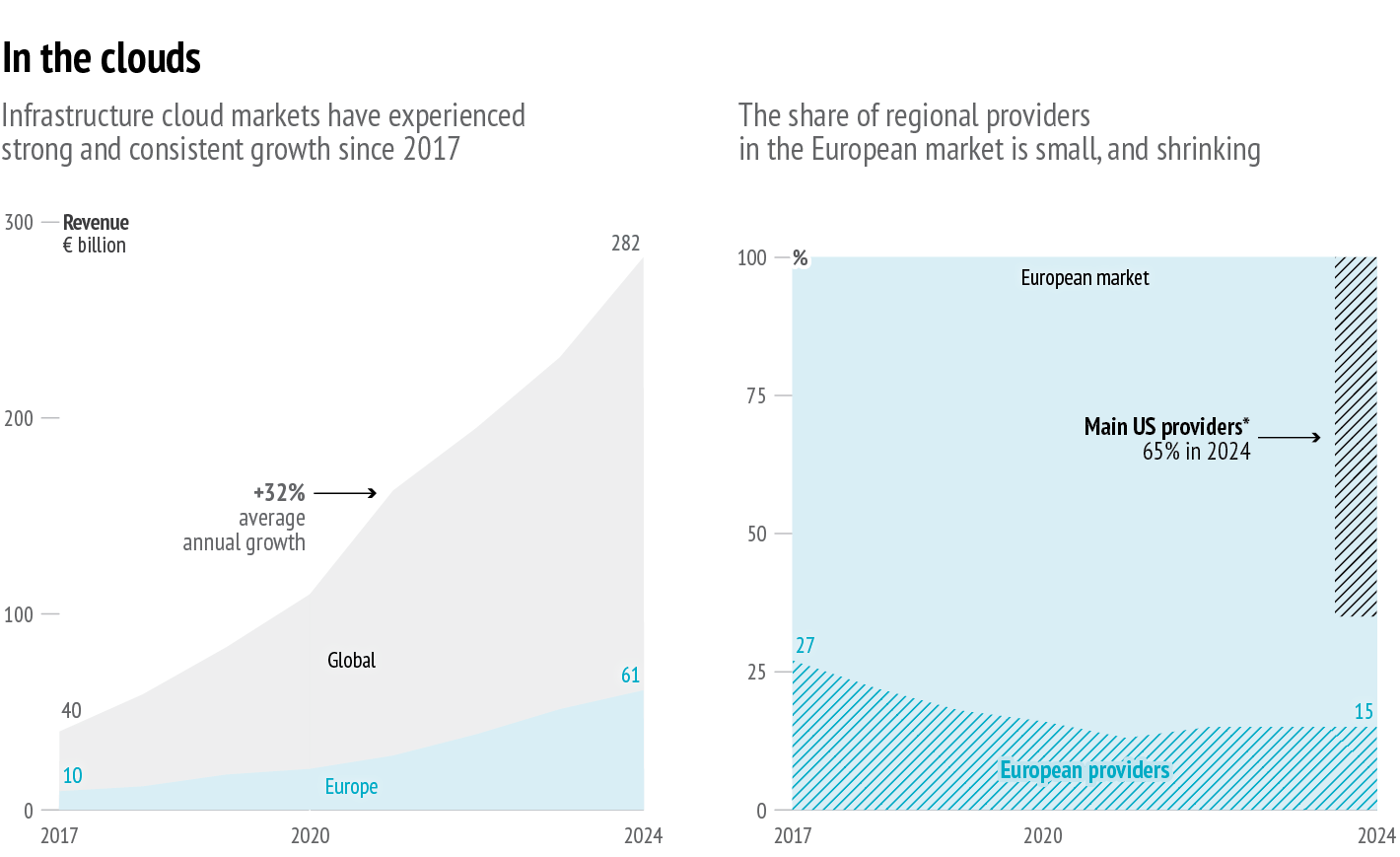

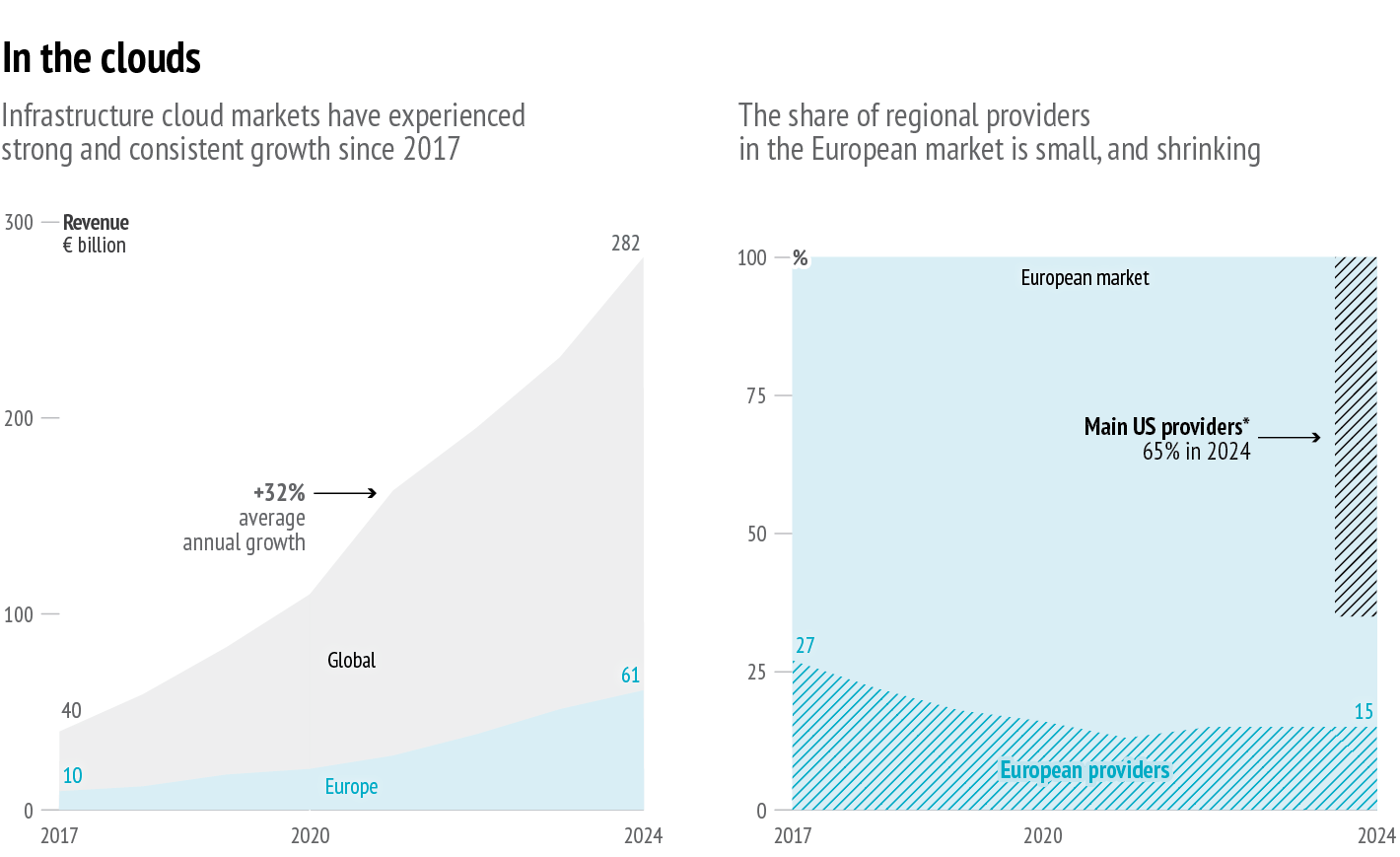

Cloud computing is a model for delivering computing services, such as processing power, data storage, application platforms and software, over the internet. Instead of owning physical hardware and installing software locally, users access resources on demand from remote data centres maintained by service providers, typically through a rental model. By enabling IT outsourcing, cloud computing has emerged as a solution to managing the exponential growth of data and the increasing complexity of ICS. It relieves users and organisations from burdensome IT tasks, reduces the costs associated with maintaining in-house infrastructure and personnel, and provides the flexibility to scale resources based on demand, especially during peak periods. This explains why the cloud sector has experienced significant and sustained growth, with an average annual increase of 32% since 2017, reaching around €282 billion in 2024 for infrastructure cloud services alone, and nearly €723 billion(1) when application services are included. These figures are expected to keep rising, as the growing use of artificial intelligence (AI) continues to drive demand for cloud services. Cloud computing has, indeed, gradually become the default way of organising ICS, now serving as a technological foundation that enables most digital services, including AI, to run and scale.

Data: SRG Research, 2025; Draghi Report, 2024; BDO, ‘European IaaS/PaaS Market’, 2024; * AWS, Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud

Beyond economic considerations, cloud computing is a strategic sector, as it has become a critical component of digital service supply chains. However, this sector is largely dominated by non-European providers. In 2025, two-thirds of the global infrastructure cloud market was controlled by American companies, with Amazon AWS accounting for 30%, Microsoft Azure for 20%, and Google Cloud for 13%. Chinese providers, notably Alibaba Cloud and Tencent Cloud, hold around 6% of the global market share(2). A similar distribution is observed in the European market, where the three American hyperscalers accounted for nearly two-thirds in 2024. In contrast, European cloud service providers are struggling to maintain their position in the regional market. While their revenues continue to grow, their share of the European infrastructure cloud market remains comparatively low and is declining, falling from 22% in 2017 to 15% in 2024. It is difficult for competitors, including European companies, to enter the market, as the cloud sector in particular benefits from economies of scale and network effects and requires massive upfront investment.

This US oligopoly creates structural dependencies that may compromise the security of Europeans’ data, particularly its availability, as shown by Microsoft’s suspected suspension in May 2025 of the International Criminal Court Chief Prosecutor’s email services, and its confidentiality, since American cloud providers are subject to US extraterritorial laws that facilitate government access to data, especially the Patriot Act, CLOUD Act, and FISA. It is this security dimension that has led some European states to call for the inclusion of a ‘sovereignty’ requirement in the EU Cloud Services Certification Scheme, the EUCS.

The EUCS ‘sovereignty’ requirement

Following the adoption of the Cybersecurity Act (CSA) in March 2019, ENISA was tasked with ‘establish[ing] and maintain[ing] a cybersecurity certification framework at Union level [for] ICT products, services, and processes’(3). In December 2020, the agency thus released the first draft of a European Cloud Certification Scheme (EUCS)(4) to define security requirements for cloud offerings, harmonise standards across Europe, boost market integration and enhance user trust. It distinguishes three assurance levels, assessing, among others, infrastructure resilience, malware protection, encryption, redundancy, and provider’s compliance. It also requires transparency on data location and legal regimes applicable to both the provider and the data.

After public consultation, the EC requested that ENISA include in the EUCS a clause for the highest security level ensuring that data would not fall under non-European jurisdictions(5). This goes well beyond the initial transparency requirement. It means that data must not only be hosted and processed exclusively within the EU, but also that providers must be headquartered in Europe and majority-owned by European entities. This amendment reflects a recognition that data localisation alone does not sufficiently protect European data from foreign intelligence access.

This new requirement has nevertheless sparked heated debate in Europe, dividing both industry stakeholders and Member States. In July 2022, Denmark, Estonia, Greece, Ireland, the Netherlands, Poland and Sweden co-signed a non-paper opposing what has come to be known as the ‘sovereignty requirement’(6). They argue that it excludes too many companies – notably American firms – and introduces political criteria into what was intended to be a technical certification scheme. Unsurprisingly, this position is shared by the American Chamber of Commerce to the EU, which, together with US industry associations, denounced the lack of transparency in the EUCS’s development process(7). France, whose national certification scheme ‘SecNumCloud’ is said to have inspired the new clause, supported its inclusion, joined by Italy, Spain and Germany. Many European cloud service providers also voiced support for the provision, urging ENISA ‘not to give in to pressure’(8).

ENISA initially aligned with proponents of the ‘sovereignty clause’ by including data localisation requirements and guarantees of the primacy of European law in the May 2023 EUCS draft. This heightened tensions. This time, a coalition of twelve Member States, led by the Netherlands, opposed the Commission’s proposal(9). US companies also issued a flurry of public statements, once again backed by the AmCham EU. The stakes are high for US cloud service providers. Although certification remains voluntary, the EU’s 2022 NIS2 Directive allows Member States to require that certain sectors or critical entities rely exclusively on providers certified at the highest EUCS level. This effectively conditions access to a significant share of European public procurement and could become a common requirement in many tenders. For some, the ‘sovereignty requirement’ is thus viewed as a protectionist measure which breaches competition law and restricts European users’ access to the most innovative and high-performing providers on the market. Others, however, argue that allowing non-European actors to control public sector or critical services information systems poses real danger, deepening Europe’s structural vulnerabilities.

These divergences reflect distinct strategic priorities among Member States. In most cases, they stem from industrial ties, the Netherlands and Poland having already, for instance, established agreements with major US hyperscalers, while many French companies have invested heavily to comply with the national SecNumCloud framework, which explicitly includes such a sovereignty requirement. In others, they derive from a different perception of threats and vulnerabilities to national ICS. For instance, the Baltic and Eastern European states, regularly targeted by Russian cyberattacks, prioritise state-of-the art protection and on-the-shelf solutions, often provided by American firms. By contrast, the Member States supporting the sovereignty provision in the EUCS, often less Atlanticist, point to longstanding concerns over data confidentiality and US intelligence agencies’ practices. They emphasise that such a ‘sovereignty provision’ would also help protect European data from Chinese laws such as the 2016 Cybersecurity Law or the 2017 National Intelligence Law.

A third version of the EUCS, issued in March 2024, then removed the ‘sovereignty requirement’, proposing to leave the matter to national regulators. Major European industry stakeholders condemned this decision(10), arguing that beyond the risk of data exposure, it would fragment the market, contradicting the purpose of the original certification framework as outlined in the CSA. Many fear ‘certification shopping’, where providers might seek to obtain the EUCS certification in states with the least stringent or most lenient conditions, resulting in market distortion and effectively lowering security standards. In September 2024, the Council of the EU urged the EC to accelerate progress, but the EUCS has yet to be adopted.

Overcoming political deadlock

Given its foundational role in AI development, including in industrial and defence contexts, and its importance in the digitalisation of European countries, the EC has recently launched a series of initiatives on cloud computing. As part of the EU’s Digital Decade agenda and under the AI Continent Action Plan, the EC is preparing both a Cloud and AI Development Act and a dedicated cloud policy for the public sector(11). Nevertheless, these initiatives cannot be fully implemented until the EUCS is adopted. There is thus an urgent need to overcome internal divisions.

The Commission is considering using the upcoming revision of the CSA, scheduled for late 2025, as an opportunity to break the current deadlock among Member States over the EUCS, by introducing ‘non-technical risk factors’ into the security certification frameworks(12). This reflects a growing recognition that data security cannot be reduced to purely technical measures. Such an approach could compel Member States to articulate more clearly the political considerations underlying their positions – an exercise that the shifting geopolitical context, in particular Donald Trump’s re-election, is likely to accelerate. Openly hostile to European regulation and repeatedly threatening to exploit the EU’s technological dependence on the US as leverage in trade wars, the American president has unwittingly given fresh impetus to the European drive towards digital autonomy, a goal explicitly stated in the Commission’s State of the Digital Decade report of June 2025(13). The issue of reliance on American cloud providers has even reached the Dutch parliament(14), where proposals aim to ensure that at least 30% of government ICS rely on Dutch or European cloud solutions(15). Denmark, already at odds with Trump over Greenland, also announced in June 2025 that it would begin migrating government systems from Microsoft to open-source solutions, a step already taken by several Danish municipalities and German states such as Schleswig-Holstein(16).

At the same time, the states most committed to integrating strict criteria, including France, have observed that the ‘sovereignty requirement’, while enhancing the transparency and robustness of services, is insufficient to curb the dominance of American providers in Europe. These hyperscalers have developed what they advertise as ‘sovereign’ regional cloud solutions which formally comply with European specifications. While these solutions provide genuine technical protection, they cannot fully eliminate the risk of external interference(17). Moreover, by also capturing the market segment reserved for ‘sovereign’ services, they further complicate the emergence of competitive European alternatives.

These developments create a potential for compromise: countries previously reluctant to endorse the sovereignty clause are now more alert to the risks of over-reliance on non-European solutions and increasingly seek mitigation measures, while advocates of strict sovereignty are beginning to acknowledge the limits of further regulatory tightening. This shared realisation could facilitate consensus around the EUCS – a momentum, albeit modest, on which decision-makers should capitalise.

No room for fragmentation

Adopting the EUCS is crucial to end the regulatory uncertainty which slows cloud deployment and the development of digital technologies such as AI across the EU. Although the ‘sovereignty requirement’ has crystallised opposition, reaching agreement among Member States requires a clear political stance that goes far beyond the scope of certification itself, reflecting broader debates on EU digital sovereignty. The discussions around the EUCS thus highlight the urgent need for a shared and actionable vision for Europe’s digital future.

References

1 ‘Gartner foresees worldwide public cloud end-user spending to total €723 billion in 2025’, Gartner, 19 November 2024.

2 ‘The big three stay ahead in ever-growing cloud market’, Statista, 21 August 2025.

3 European Union, ‘Cybersecurity Act’, 17 April 2019.

4 ENISA, ‘EUCS – Cloud Services Scheme’, December 2020.

5 ‘Sovereignty requirements remain in cloud certification scheme despite backlash’, Euractiv, 16 June 2022.

6 ‘Germany calls for political discussion on EU’s cloud certification scheme’, Euractiv, 21 September 2022.

7 AmCham EU, ‘Joint industry statement on the European Cybersecurity Certification Scheme for Cloud Services’, Position Paper, Brussels, 14 June 2022.

8 Global Security Mag, ‘Lettre ouverte commune sur les « critères d’immunité aux lois extraterritoriales » dans le système de certification européen destiné aux services cloud’, July 2022.

9 ‘Les Pays-Bas rassemblent les opposants à la certification cloud européenne’, Euractiv, 6 December 2023.

10 ‘European industrial giants condemn latest EU cybersecurity agency decision on cloud sovereignty’, Euractiv, 10 April 2024.

11 European Commission, ‘Cloud and AI Development Act. Call for evidence for an impact assessment’, Brussels, 9 April 2015.

12 European Commission, ‘Revision of the Cybersecurity Act. Call for evidence for an impact assessment’, Brussels, 11 April 2025.

13 European Commission, ‘State of the Digital Decade 2025: Keep building the EU’s sovereignty and digital future’, Brussels, 16 June 2025.

14 ‘“A threat to autonomy”’: Dutch parliament urges government to move away from US cloud services’, Euronews, 20 March 2025.

15 ‘Microsoft didn’t cut services to International Criminal Court, its president says’, Politico, 4 June 2025.

16 ‘Caroline Stage is phasing out Microsoft in the Ministry of Digitalization’, Politiken, 9 June 2025.

17 ’Commande publique: audition de Microsoft’, Direct Sénat, 10 June 2025.