Explore the interactive introduction below to discover the main themes and chapters. Full report available for download.

Facing the facts

A sea change in transatlantic relations

Less than a year into Donald Trump’s second term, the transatlantic relationship looks profoundly different. A complete rupture between the United States and Europe has not taken place. However, transatlantic trust has been shattered. And we must now move forward in a low-trust environment.

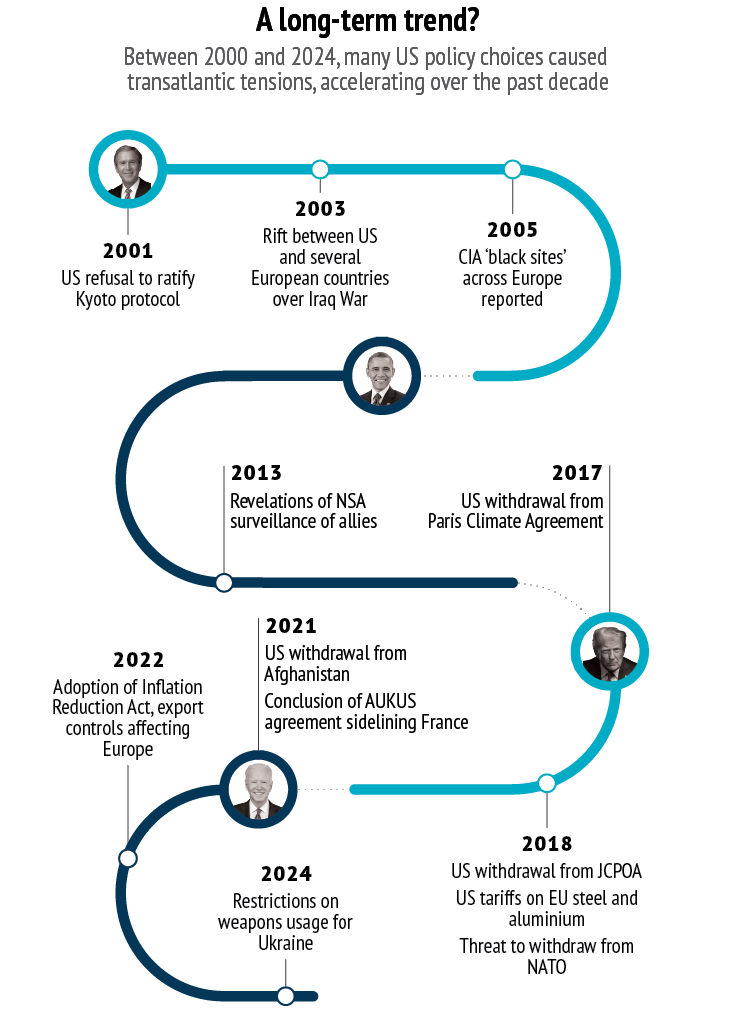

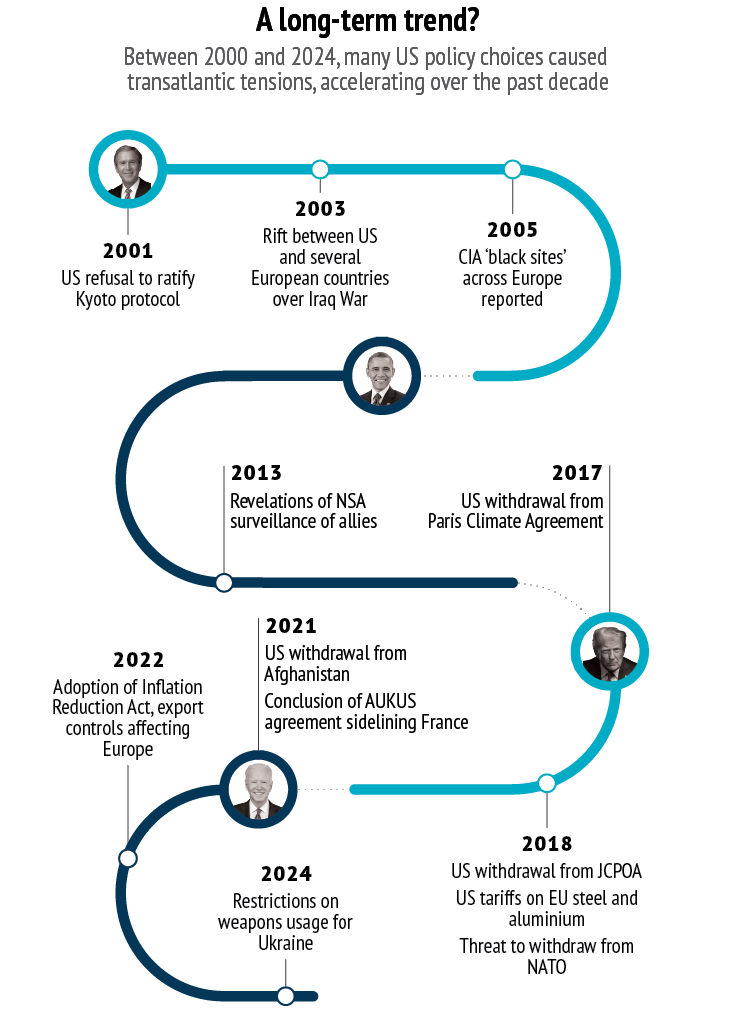

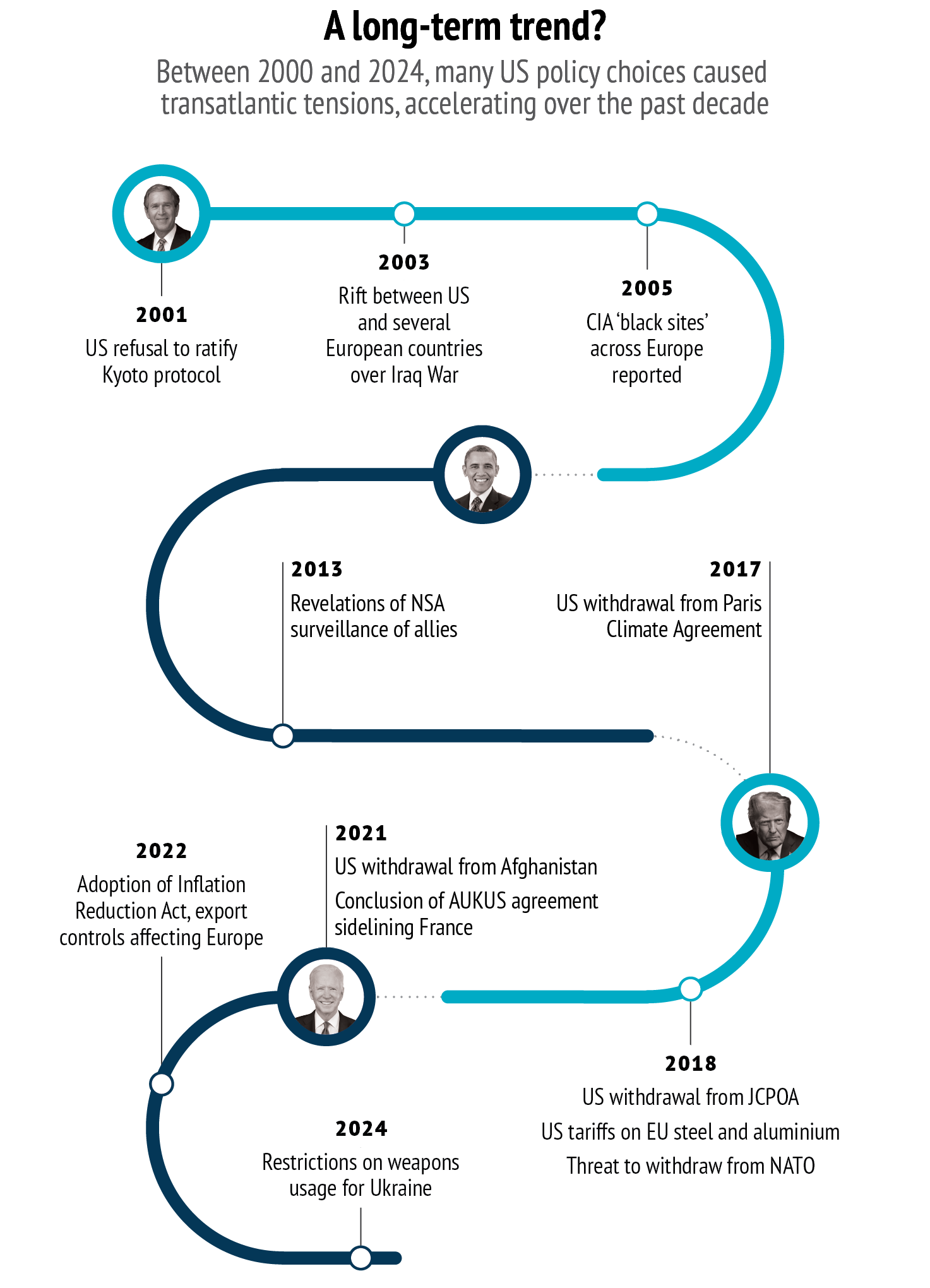

Episodes of tension in transatlantic relations are not new. There are many examples in the post-war period – from rifts over the Vietnam war, to the cruise missile crisis, to the Iraq war and the Snowden spying revelations, culminating in the major trade clashes during Trump’s first term. While the Biden administration was keen to restore the transatlantic partnership overall, tensions still emerged on military agreements (AUKUS), subsidies to industry (the Inflation Reduction Act) and the extent of support to Ukraine.

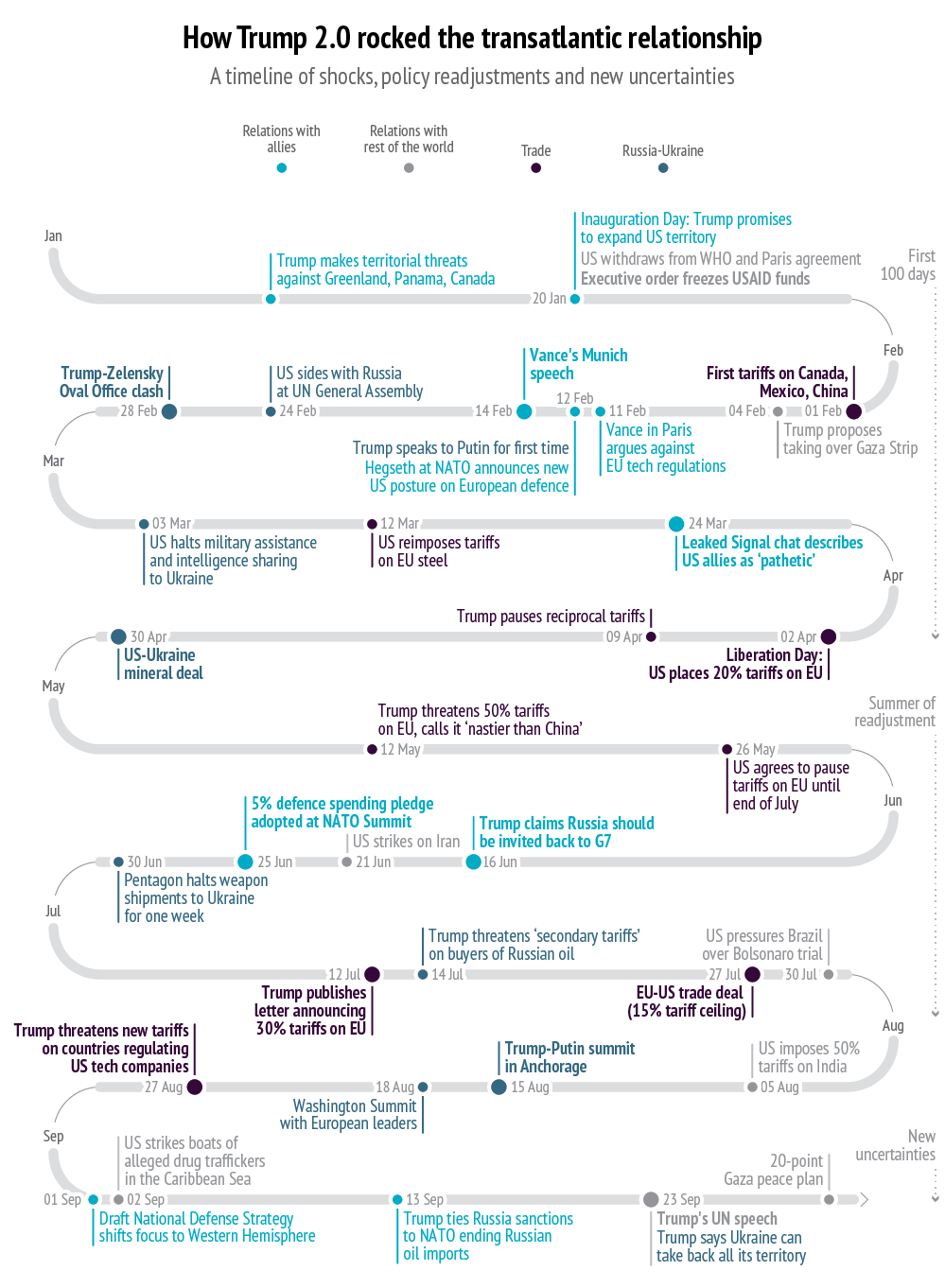

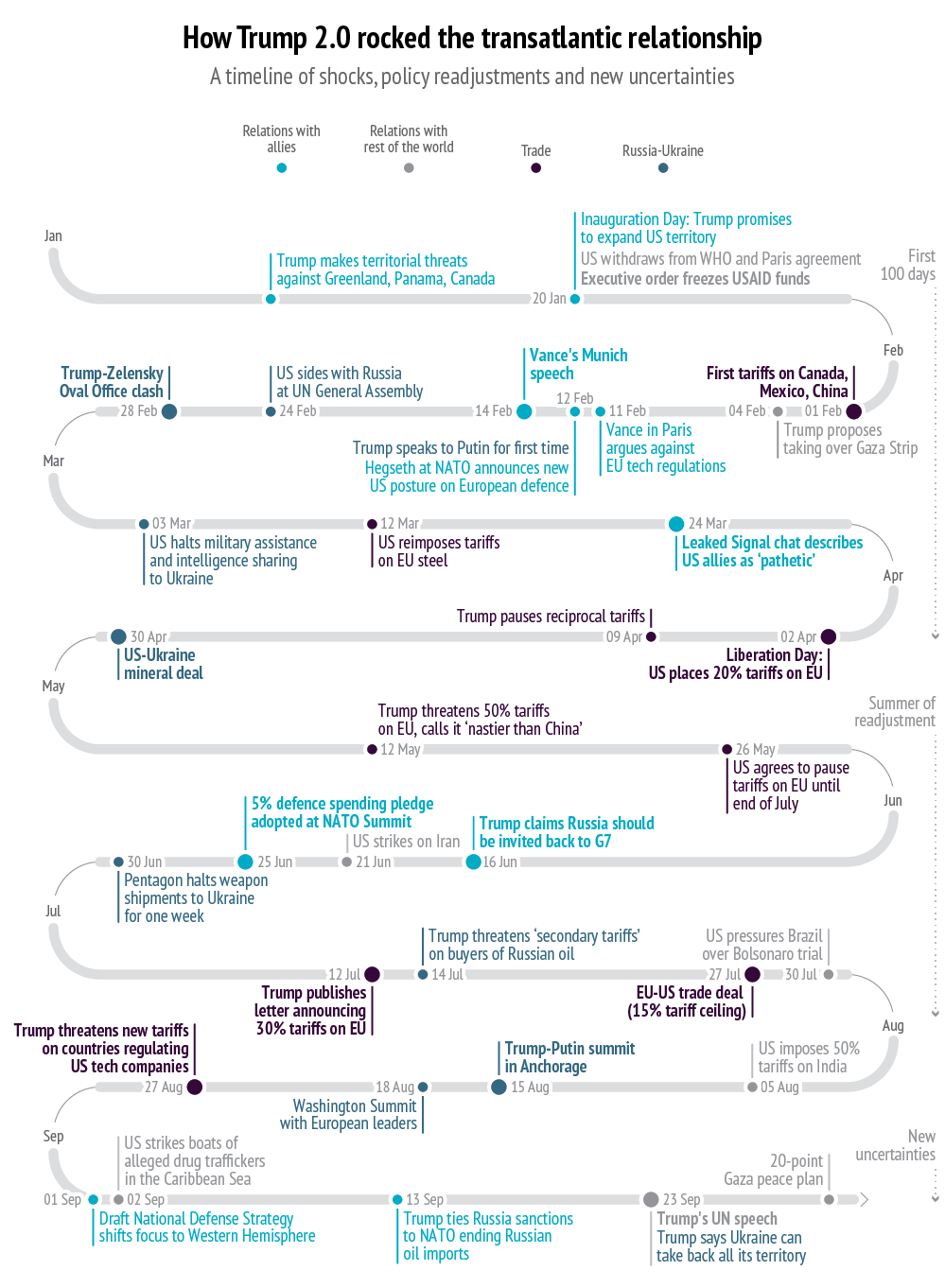

However, what has unfolded in 2025 goes several steps further, both in qualitative and quantitative terms. A glance at the year’s timeline (see page 4) reveals the scale of the disruption the second Tump administration has unleashed across trade, alliances, and the global order. The first 100 days were particularly disruptive, both in rhetoric and policy, giving the impression that the US was targeting its own allies. The summer of 2025 was slightly more constructive, with Washington and Europe striking agreements on NATO, Ukraine and trade. However, relations are not back to how they were prior to Trump 2.0. The new administration’s actions, wittingly or not, have undermined the foundations of transatlantic trust.

The first 100 days were particularly disruptive, both in rhetoric and policy, giving the impression that the US was going after its very allies.

The summer of 2025 was slightly more constructive, with Washington and Europe striking agreements on NATO, Ukraine and trade.

However, relations are not back to how they were prior to Trump 2.0. The new administration’s actions, wittingly or not, have undermined the foundations of transatlantic trust.

Trusted partners tend to share a vision of the world, built on common interests and values. They work together to accomplish shared goals, consulting each other on the steps to take, and having a clear understanding of what the partner will do next (2). They include formats and institutions for dispute resolution, so that temporary tensions do not end up destroying trust in the long run (3). The transatlantic relationship used to display all of these elements.

However, under Trump 2.0 these features are all being unravelled. This is most visible in three areas:

From common values to hostility: For 80 years, American foreign policy objectives included support for the legitimacy, integration and security of European democracies (4). Trump questioned this commitment during his first term. During his second term, he has taken additional steps. Not only is the US seeking to rebalance away from Europe – an established trend in US foreign policy that predates Trump, but which has been accelerated by the new White House (5). This administration has also displayed elements of active hostility against the European project. Trump has described the EU as a globalist entity that aims to ‘screw’ the US while freeriding on American protection (6). He has refused to rule out the use of force to annex Greenland, the territory of an EU Member State and NATO ally. At the Munich Security Conference, Vice-President Vance called attempts to curb disinformation a bigger threat to Europe than Russia and China. In May, the State Department published a memo accusing Europe of carrying out an ‘aggressive campaign against Western civilization itself’ (7). In August, the State Department instructed US embassies in Europe to actively counter EU regulations on digital services (8).

Careful diplomatic action from European heads of state persuaded the president to veer away from some of these extremes. He changed his rhetoric on NATO, declaring that the alliance ‘isn’t a rip-off’, after the allies pledged to spend 5% of GDP on defence. Yet elements of hostility to Europe are embedded in ideological programmes like Project 2025 (9), remain entrenched within Trump’s coalition, and continue to shape US foreign policy and its approach to Europe (10).

Trump’s volatility and unpredictability: Being able to predict partners’ likely behaviour is essential for planning purposes and for cooperation. But under Trump 2.0, transatlantic unpredictability has become the norm. The President has reversed policy decisions in a matter of days, if not hours, in ways that have been hard to predict.

The EU-US trade negotiations highlight this dynamic. Trump began the dispute with a 20% ‘reciprocal’ tariff across the board, which was taken down to 10% one week later after market turmoil. When an EU-US agreement appeared within reach, the president suddenly issued a ‘letter’ announcing levies of 30%, once again blindsiding EU negotiators. The 15% tariff ceiling agreement was hailed in Brussels as ‘the best possible deal given the circumstances’ (11) – as the EU avoided the 50% levies that India and Brazil are now facing. But as the general agreement is implemented, more issues will emerge which could lead Trump to reverse course again. For instance, since concluding the trade deal, the US has threatened more tariffs in response to EU tech regulation of American companies operating inside the EU.

Volatility is also evident in Trump’s Ukraine policy. Trump shifted from blaming Ukraine and blocking intelligence to Kyiv to reversing the Pentagon’s decision to halt weapon supplies and promising sanctions on Russia. These partial reversals have been taken as a sign that Trump’s extremes will give way to a more conventional administration, like in the first term (12). However, European countries fear that a single meeting could undo months of diplomatic engagement. For instance, Trump backtracked on the sanctions threat after the Alaska summit with Putin and the measures have never materialised. And the US only allows European countries to buy US weapons; it no longer donates any weapons to Ukraine.

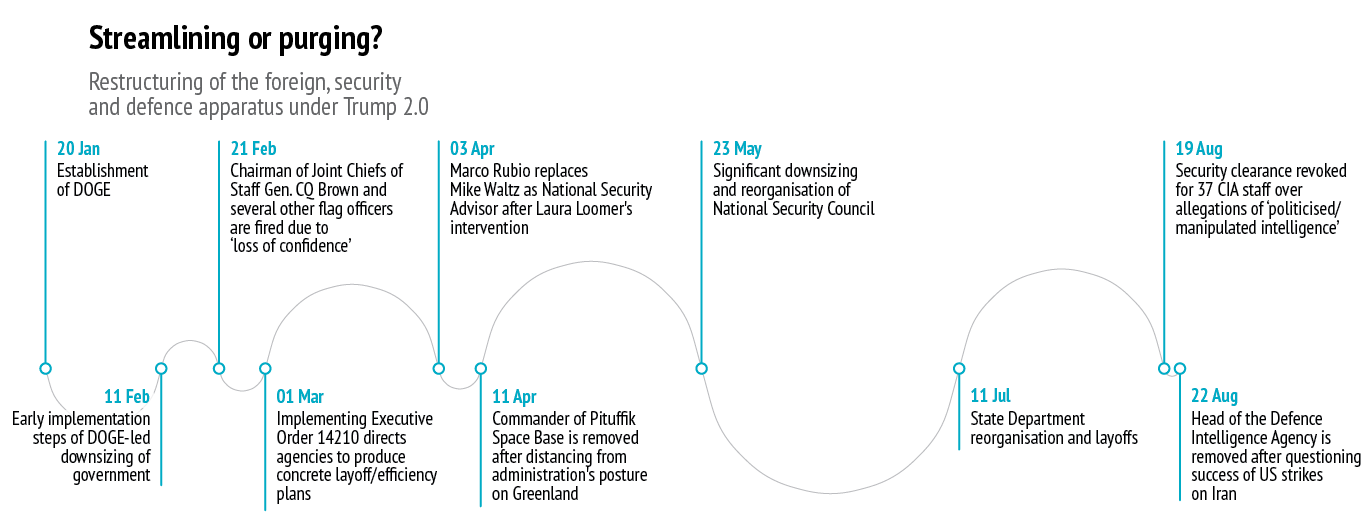

Policy process: loyalty over competence? While there was unpredictability during Trump 1.0, checks and balances within the administration and the Republican party curbed the president’s most unconventional ideas. Now, those bulwarks are mostly gone. Trump is in full command of his party – and elected officials are unwilling to challenge him ahead of the midterms. ‘America First’ is not a doctrine: it essentially coincides with whatever Trump decides.

The policymaking process has also changed significantly. Groups that in the view of the president obstructed his work during the first term, like the National Security Council, have been sharply reduced in size, resulting in a messier inter-agency coordination process, and potentially hampering policy development (13). At the same time, officials who questioned the effectiveness of the administration’s policy – such as the strikes on Iran – or were associated with past probes into the 2016 election, have been removed or have had their security clearance revoked (14). These cuts are eroding the expertise held within the US government, and weakening incentives to present alternative or critical viewpoints.

All of the above – Trump’s own volatility, the premium on loyalty over expertise, and the presence of hostile elements – contribute to breaking trust. Europeans cannot be certain that the US will adhere to the new agreements made in the summer. It has become harder to predict and influence US policymaking through traditional channels. Instead, leaders have to go all the way to the president – e.g., at the hastily organised Washington Summit in August.

In 2016 many Europeans thought that Trump 1.0 was an historical exception: after the 2020 election, the relationship would return to normal – with episodes of tension, but institutions to manage them. This time, it is far harder to make that claim. Trump’s re-election shows the enduring appeal of his message to the American electorate. Most surveys show increasing scepticism by US citizens towards international institutions, alliances, and permanent American involvement abroad (15). The hostile elements who want to unravel the relationship with Europe will likely be a long-term feature of American politics, and Europe will need to learn to live with them. And the changes to the way the US government works – where loyalty is prized over competence – could be hard to undo. Hence, the erosion of transatlantic trust might be permanent.

The majority of European publics seem to understand this. According to a Pew Research Center survey, favourable European attitudes towards the US dropped by 12.9% between 2024 and 2025 (16). Many Europeans now regard the US as a ‘necessary partner’ rather than a trusted ally (17). Even more ominously, another survey found that Europeans consider Trump an ‘enemy of Europe’ (18). It is unlikely that these perceptions will change dramatically in the near future.

But Europe is not alone in experiencing this erosion of trust. Countries across the world – especially US allies – are grappling with the same factors and frustrations. Some are witnessing the weaponisation of tariffs for political purposes. Others have perceived abandonment by their main security provider, or even territorial threats. Many countries and populations that relied on US foreign aid will now have to make do without it. Some have already taken steps to adapt to an age of low trust in the US – with important lessons for Europe. An analysis of the demise of transatlantic trust would be incomplete if it ignored the international context and the experiences of other partners.

Of course, there are also people in Europe and beyond who have welcomed Trump’s new approach. At the time of writing, Trump’s unconventional diplomacy appears to have brought about a ceasefire in Gaza – a positive development. At the same time, illiberal and authoritarian actors see opportunities to strengthen ties with a Washington that is less concerned with combating autocracy. Populist forces regard Trump as the standard-bearer of their movement, and a catalyst for their own political ambitions. Traditional US adversaries like Russia and China have approached Trump 2.0 with cautious optimism, hoping to exploit weakening ties between the US and most of its traditional allies. While Trump 2.0’s volatility has also affected them – Iran, for instance, initially welcomed a less interventionist US approach but later suffered a US strike on its nuclear facilities – these actors ultimately stand to gain from the erosion of trust between America and its allies.

Exploring the erosion of trust across issues and regions

This Chaillot Paper explores how the erosion of trust has unfolded across different dimensions of the transatlantic relationship: what has changed? What strategic debates have emerged? How should Europe’s relationship with the US evolve in a low-trust environment? In the second half of the study, we ask how other actors across the world have coped with similar breaches of trust: did they experience the same feeling of broken trust as Europe? Did they see it coming, and were they more prepared? What should Europe learn from them, and how can it present itself as a useful partner in these uncertain times? We tackle these questions in 11 distinct chapters.

The issues: manageable differences or deep rifts?

The size of the trust deficit varies across different domains of the transatlantic relationship. In some areas, Europe and the US could continue working together to pursue aligned interests, but uncertainty and mistrust could also magnify existing differences, straining the relationship. In other areas, the misalignment between US and European objectives is bigger, making it even harder to find common ground moving forward – and US policy could even run counter to Europe’s interests.

The regions: partners in need and models to learn

As mentioned above, Europe is not alone in experiencing a transatlantic rift. Countries across the world are also losing trust in the US. Some are re-evaluating their relationship now, while others had already begun to do so well before Trump’s second term. These countries are looking for trusted partnerships to compensate for the vacuum left by Washington. Should Europe fail to provide a concrete alternative, others will surely step in to fill the gap. At the same time, many of these countries can provide valuable lessons on dealing with the US in a climate of diminished trust.

Advancing transatlantic relations under low trust

Europe faces a dilemma. On the one hand, the transatlantic relationship and cooperation with the US remain crucial. The challenges Europe faces have not gone away, and it needs to cooperate with the US where feasible. On the other hand, transatlantic mistrust will persist for a long time. There is no clear way of returning to a normal relationship. In some areas, the US may come to be seen less as a fully-fledged ally and more as a ‘necessary partner’ (19). In other areas, US policies may run counter to Europe’s interests, which will need to be defended.