The release of a new AI model by the Chinese startup DeepSeek in January 2025, known as R1, captured global attention. The company claimed to have developed a model that performs on par with those of leading American tech firms such as OpenAI, xAI or Anthropic, but at significantly lower cost and requiring far less computing power. This announcement sent shockwaves across the globe, signalling a potential reshaping of the global AI race between the US and the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

China’s restricted access to cutting-edge chips due to American export controls had led many to doubt its ability to develop a frontier AI model. The release of DeepSeek’s model has challenged those assumptions, calling into question the effectiveness of the US’s ‘small yard, high fence’ strategy. Crucially, the Chinese firm’s breakthrough relies primarily on the model’s algorithmic efficiency, dealing a serious blow to the technical and business model long championed by US tech giants. Although its technological advances are noteworthy, DeepSeek’s disruptive impact thus lies in its challenge to a once-dominant paradigm, opening the door to alternative AI models.

The DeepSeek ‘revolution’

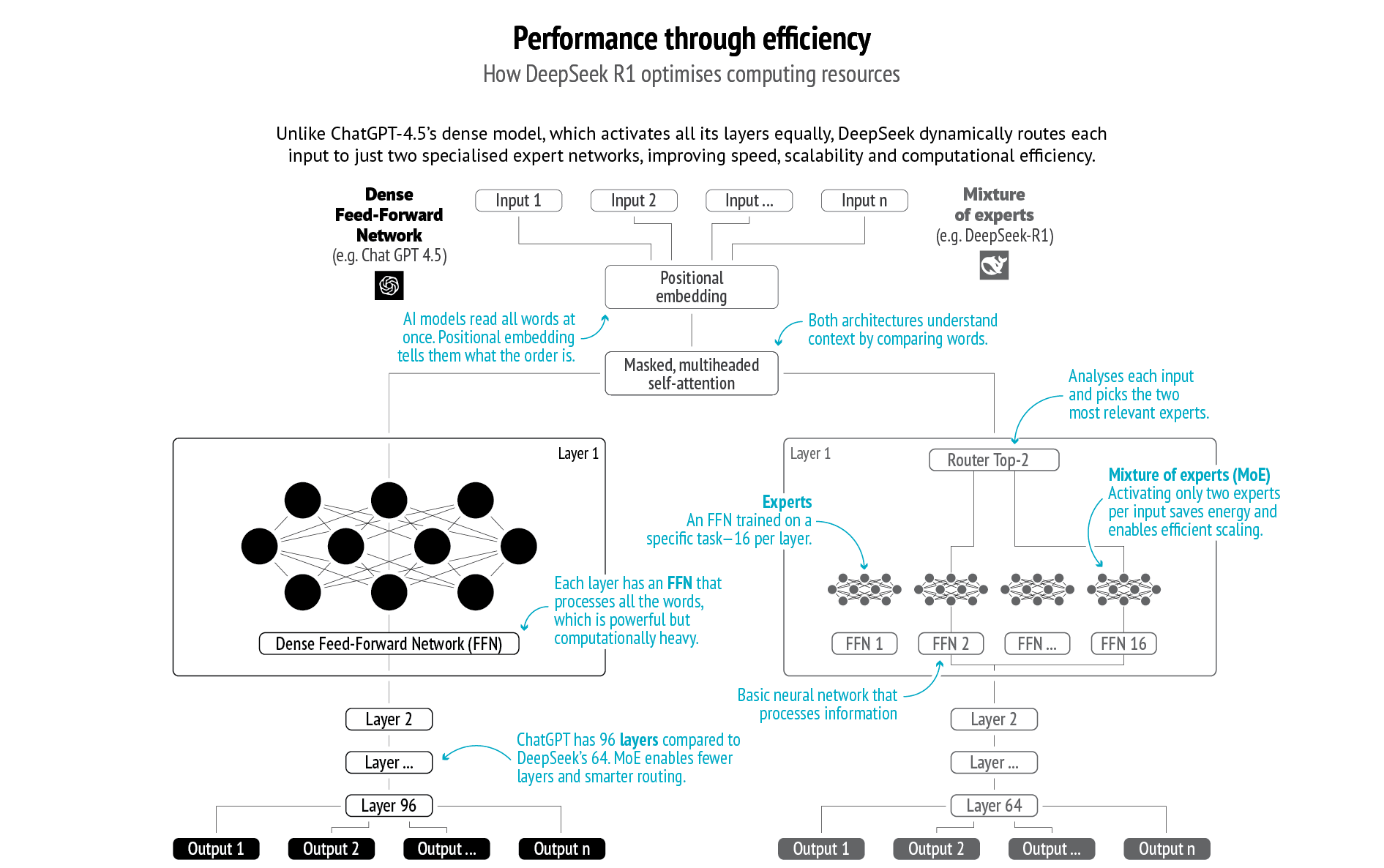

In reaction to US export controls, DeepSeek compensated for the computing power shortcomings it faced by improving its model’s efficiency. In particular, it focused on inference enhancement, generating text faster, at lower cost, and with higher quality, once the model is trained. Techniques such as mixture-of-experts (MoE), selective activation, and transfer learning allow for the optimisation of computational resources(1). In particular, the MoE architecture activates only a few relevant subnetworks of the model during the inference, which significantly reduces computational overhead. Not only does compute efficiency reduce reliance on US chip supplies, but DeepSeek also proves that while export restrictions may slow down technological progress, they can simultaneously incentivise creative approaches to make up for limited computing power.

Even so, Chinese AI development is not fully autonomous. DeepSeek’s techniques build on foundational research developed by other firms, notably Meta’s LLaMA series. DeepSeek has also acknowledged using US-manufactured Nvidia chips instead of Chinese semiconductors. Without access to US research and hardware, DeepSeek would thus have not achieved what it did. In addition, despite notable progress by Chinese chipmakers, competing with the technological sophistication of American AI chipsets, especially for compute-intensive pre-training, will remain a significant challenge in the coming years. Beyond hardware dependencies, R1 has three disruptive effects: it allows for alternative models; amplifies risks; and accelerates the pluralisation of AI development.

Data: Zhang, S. et al., ‘A survey on mixture of experts in large language models’, 2024; DeepSeek, ‘DeepSeek-VL: Scaling Vision-Language Models with Mixture of Experts’, 2024; Daily Dose of DS, ‘Transformer vs. Mixture of Experts in LLMs’, 2025

Room for alternative models

R1 is not a fully open-source model as DeepSeek did not release its complete training data or codebase; but it is an open-weight model, meaning its trained parameters – the weights – are publicly available, allowing others to use, fine-tune and deploy the model. It thus makes AI accessible and usable to a broader range of actors with limited technical expertise or computing resources. DeepSeek R1 is also released under the MIT License, making it freely available for commercial use. This lowers the barrier to entry for actors lacking capital or infrastructure and facilitates the development of AI applications across sectors like finance, manufacturing or healthcare. Additionally, by focusing on algorithmic innovation and cost reduction, DeepSeek establishes efficiency as a new key parameter for future frontier AI innovation. As computing power is becoming a critical asset, resource optimisation could be a decisive factor in the AI race.

DeepSeek thus embodies a shift from the prevailing business and technical model based on closed-source, proprietary and scale-first AI development towards more flexible and resource-conscious approaches. It not only challenges the widespread ‘winner-takes-all’ assumption in the digital sector, but also raises the question of whether smaller-scale companies, including European ones, could make significant progress with ‘good enough’ AI models. Such models, while not necessarily state-of-the-art, can perform specific tasks effectively within a given context, prioritising practical utility, affordability and accessibility. They are particularly useful for edge models (especially the Internet of Things), chatbots, transcriptions or machinery monitoring.

Amplifying risks

The release of R1 has also raised several security-related concerns. The first issue is data security and privacy. DeepSeek’s terms of service indicate that user data may be stored in China and used for training purposes, raising serious questions about compliance with international data protection standards, including the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The Personal Information Protection Commission (PIPC), South Korea’s national data protection authority, has reported that personal information from over a million South Koreans was transferred to China without consent(2). Suspicions about potential backdoors enabling government access have deepened mistrust, especially given China’s recently amended Intelligence Law, as it includes a blanket requirement for Chinese entities and individuals to cooperate with Chinese security services(3). This has led countries such as Australia, India, Italy and Taiwan to ban DeepSeek from government devices. Nonetheless, such concerns are neither new nor unique to China. The DeepSeek controversy has reignited broader debates about data surveillance and the role of intelligence agencies, particularly given the close ties between the US government and major American tech firms.

DeepSeek has also faced criticism for adhering to Beijing’s content regulations on politically sensitive issues such as the Tiananmen Massacre, Taiwan and the repression against Uyghurs, leading to accusations of restricting data access and embedding ideological bias. While censorship only applies to the online version, the model is likely to reflect the authoritarian context in which it was developed, as any AI model is shaped by its training data and the political values it embeds. DeepSeek has also fallen short in protecting sensitive user data, including chat histories and authentication keys(4), raising concerns about both free speech and cybersecurity.

Beyond these immediate normative and security issues, DeepSeek’s ambition to develop AI models approaching or exceeding human cognitive abilities, known as artificial general intelligence (AGI), is the most concerning. Advancements in this field would not only exacerbate tensions in the US-China AI race leading to the development of unsafe models, but could even lead to the development of AI systems escaping human control. Robust multilateral frameworks for AI governance are urgently needed.

The pluralisation of AI development

The emergence of alternative models and the amplification of risks both stem from and reinforce the pluralisation of AI development. This refers to the increasing diversification of actors, technical architectures and strategic approaches across both technological and geographical dimensions, as new initiatives worldwide contribute to the formation of distinct and sometimes competing AI ecosystems.

The growing risks related to AI development have reinforced China’s long-standing drive to tighten state control over digital technologies and oppose US dominance in international Internet governance. While this stance initially resonated with authoritarian regimes such as Russia and Iran, since the second half of the 2010s even democratic states have started to question their technological dependence on the US and the implications for data security. Over the past five years, European countries have pursued greater technological autonomy and launched initiatives to position Europe as a potential global hub for AI. Mounting concerns about the concentration of power among US tech giants have also spurred efforts to foster AI development globally. Many actors, such as the African Union, Brazil, Canada or Australia, are launching their own AI strategy, with over 70 countries already having implemented AI policy initiatives by mid-2023(5). Even if they may not be able to compete with the US or China yet, new AI development hubs are also emerging. The Gulf countries, for instance, plan massive investments to establish data centres and research facilities domestically and abroad. AI is also a political priority for India, which co-organised the Paris 2025 AI Action Summit and is working to build indigenous capabilities, with the goal of taking a leadership role in the Plural South. As for South Korea and Japan, they have established themselves as key players in hardware and manufacturing, niche and industrial AI applications, as well as robotics. While neither of these countries is close to rivalling the US or China yet, their distinct strategic approaches, sectoral strengths and sustained investment efforts position them as credible and increasingly influential actors.

By challenging the narrative of unshakeable US dominance, the release of DeepSeek R1 has actively contributed to this growing pluralisation of the AI landscape. At the same time, it has reignited competition, prompting the American ecosystem to further accelerate its efforts in what US President Donald Trump described as a ‘wake-up call’(6), and leading Washington to introduce new export controls on semiconductors. However, tighter controls are likely to further accelerate China’s long-standing drive for technological self-reliance, a goal reiterated by President Xi Jinping’s recent call for AI self-sufficiency(7). The lifting of restrictions on Nvidia’s H20 chips will not change China’s calculus, as Chinese companies like Huawei and Alibaba continue to advance domestic AI alternatives, from Huawei’s stockpiling of Ascend 910B chips and the deployment of CloudMatrix 384, to Alibaba’s expansion of the Qwen model family.

An opening for the EU

The pluralisation of AI presents an opportunity for the EU to promote its own models, grounded in European values and whose advancement and widespread adoption would bolster the European digital industrial ecosystem.

The EU has made significant progress in developing its AI capabilities and in regulating the sector, including through the 2024 AI Act and the AI Continent Action Plan of April 2025. Nonetheless, given the growing geopolitical uncertainty surrounding digital technologies, the EU should step up its efforts. To cope with existing risks, it should continue enforcing strict ethical and security standards. Policymakers must ensure AI regulations uphold democratic values while mitigating potential security threats from foreign models. The EU should also take advantage of the opportunities presented by DeepSeek. While investing in high-performance computing capabilities and digital infrastructures remains crucial, the EU appears to be overlooking compute efficiency in its AI Continent Action Plan. Yet, addressing this issue would support the EU’s broader objective of widespread AI adoption. At the moment, end-user industries are reluctant to implement AI, mainly because of the fast pace of model advancement. By the time an application is operational, a new and better AI model is likely to be released, rendering the initial investment obsolete. However, models that are ‘good enough’ for a wide range of uses are likely to emerge soon. Europe’s competitiveness will then also depend on broad industrial and societal uptake. The EU should thus actively support experimentation with AI industrial applications, as this would not only foster innovation but also help European companies scale up – currently the biggest challenge facing Europe’s digital ecosystem. A stronger European AI industry would also help to effectively defend privacy, data security and democratic values.

Conclusion

The release of DeepSeek R1 marks a disruptive milestone, validating the emergence of credible alternatives to AI models developed by American tech giants. It is thus accelerating the ongoing pluralisation of the global AI landscape, a phenomenon driven not only by systemic rivalry among leading digital powers but also by mounting political instability. In this context, states are increasingly seeking to limit their dependencies, bolster their domestic capabilities and increase diversification, leading to a multiplication of AI ecosystems globally. This pluralisation of the AI landscape could either be a security liability for the EU if left unaddressed, or an economic, industrial and strategic opportunity.

References

* The authors would like to thank Alessia Caruso, EUISS trainee, for her research assistance.

- 1 Liang, W. et al., ‘DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in LLMs via reinforcement learning’, arXiv, 22 January 2025.

- 2 ‘South Korea says DeepSeek transferred user data, prompts without consent’, Reuters, 24 April 2025.

- 3 ‘PRC National Intelligence Law (as amended in 2018)’, China Law Translate.

- 4 Burgess, M. and Newman, L.H., ‘DeepSeek’s safety guardrails failed every test researchers threw at its AI chatbot’, Wired, 31 January 2025.

- 5 OECD, ‘AI principles’, 2024.

- 6 Körömi, C., ‘Trump: China’s DeepSeek AI is a “wake-up call” for US tech’, Politico, 28 January 2025.

- 7 ‘Xi Jinping urges promoting healthy, orderly development of AI’, National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, 26 April 2025.