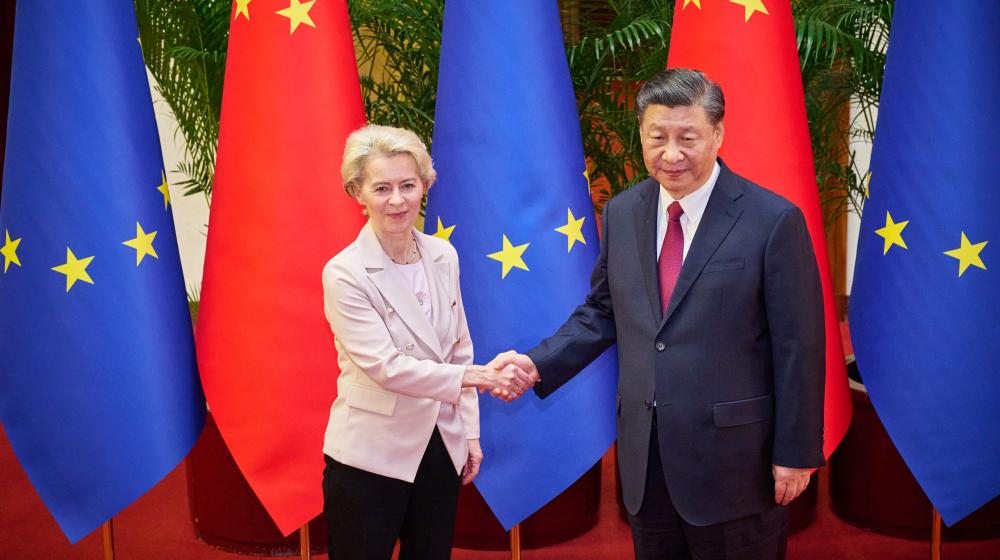

When EU leaders travel to Beijing this Thursday for the EU-China Summit, everything might seem to be business as usual at first glance. Since 2019, both sides have failed to agree on a joint declaration, with each summit overshadowed by clashing interests and diverging views. This time, the immediate points of contention include reciprocal restrictions on the procurement of medical equipment, EU tariffs on heavily subsidised Chinese electric vehicles, and Chinese export controls on heavy rare earth elements and other critical raw materials. China’s close partnership with Russia continues to strain relations with the EU. According to the South China Morning Post, earlier this month China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi conveyed to EU foreign affairs chief Kaja Kallas that Beijing remains opposed to any outcome in Ukraine that would result in a Russian defeat.

China’s close partnership with Russia continues to strain relations with the EU.

The appearance of business as usual contrasts with the broader uncertainty that has characterised international affairs since the election of Donald Trump. With the transatlantic relationship under strain, there have been expectations that China would pursue a hedging strategy in an effort to exploit tensions between the EU and the United States. Only a few months ago, observers feared that US pressure might compel the EU to accept almost any deal with Beijing, even at the expense of its own core interests. Conversely, projections that the EU might seek to ease transatlantic tensions by sacrificing its relations with Beijing have also failed to materialise.

China's waning interest in Europe

In theory, the EU-China Summit should have been a celebratory occasion in Brussels, marking 50 years of diplomatic relations. However, Xi Jinping’s decision not to travel to Europe, alongside other recent signals, made it clear from the outset that Beijing’s focus lies not on Europe but on the Global South. Although China has been closely observing transatlantic dynamics, its approach has remained largely defensive and characterised by a wait-and-see posture.

Projections that the EU might seek to ease transatlantic tensions by sacrificing its relations with Beijing have failed to materialise.

Despite this cautious stance, Beijing signalled renewed interest in engaging with Europe through a series of high-level delegations aimed at gauging EU priorities. China lifted certain sanctions on European institutions, such as the Human Rights Committee of the European Parliament, as well as on individuals, including recently former MEP Reinhard Bütikofer. In a phone call with Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, Premier Li Qiang agreed to set up a working group to examine the issue of trade diversion. In the dispute over electric vehicles, both sides reached a technical-level agreement on a price undertaking intended to produce an effect equivalent to that of the current tariffs. Beijing seemed to hope that these largely symbolic concessions might revive the relationship.

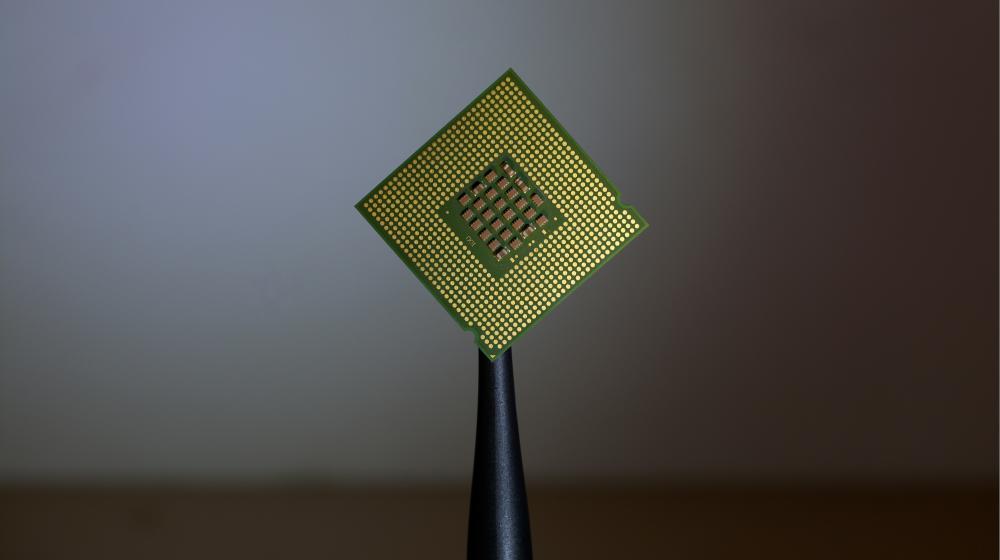

But after China reached an agreement with the US to ease their trade tensions in Geneva in May, Beijing’s already limited interest in Europe quickly faded. In June, a follow-up deal in London led both sides to lift retaliatory measures, although they failed to address Trump’s original grievance: the US trade deficit. China had shown greater staying power than the Trump administration. Beijing’s confidence was further bolstered by the release of DeepSeek’s AI model, despite ongoing US export restrictions.

Beijing’s confidence was further bolstered by the release of DeepSeek’s AI model, despite ongoing US export restrictions.

While the EU wrestled with Washington’s unpredictability, Beijing had manoeuvred itself into a more comfortable position. In the meantime, China’s appetite for compromise with Brussels has significantly declined. Its leadership is now withholding support for both the proposed price undertaking and the establishment of a trade diversion monitoring mechanism.

Washington's reluctance to pursue a joint China policy

Washington, for its part, has reacted with surprising passivity to the idea of coordinating a joint China policy with Europe. Although China occasionally features in transatlantic trade talks, it has only recently – and only minimally – become a substantive topic in EU-US negotiations.

Part of the reason may lie in the erratic nature of the Trump administration, which tends to prioritise unilateral action over international coordination. Vice President J.D. Vance’s speech at the Munich Security Conference underscored that not everyone in Washington views authoritarian China as the primary rival — some instead see liberal Europe as the adversary.

Not everyone in Washington views authoritarian China as the primary rival — some instead see liberal Europe as the adversary.

Trump himself is not a China hawk. His priority is reducing the US trade deficit with China, rather than addressing national security threats, as many in Washington believe is necessary. Furthermore, many observers question just how aligned the US and Europe truly are on China. In private conversations, even former Biden administration officials express frustration over the time and effort spent coordinating with European counterparts, only to achieve limited results. The suspicion lingers that Europe is more interested in preserving its lucrative commercial relations with China — even if that entails significant security risks.

What to make of the summit

At first glance, the EU’s top leaders may be heading into yet another routine summit with China. But the geopolitical context has changed. For years, Beijing approached Brussels with the underlying assumption that Europe was merely following Washington’s lead rather than pursuing its own strategic interests. Now, China may be realising that, despite ongoing tensions in the transatlantic relationship, the fundamental divergences between EU and Chinese interests have largely remained the same.

This underscores just how challenging the path towards greater EU-China cooperation will be. If Beijing has even a peripheral interest in improving relations, it must address the EU’s three core and long-standing concerns:

- China’s enabling role in Russia’s war against Ukraine, which poses a direct threat to the European security order.

- The impact of massively subsidised Chinese overcapacity, which undermines the competitiveness of European industries.

- China’s use of export controls and supply chain leverage, which compromises Europe’s economic security.

All too often, European and Chinese leaders fall back on maximalist positions while limiting progress to less strategic areas such as trade in cosmetics or agriculture. This time, however, EU leaders could try to take advantage of the waning momentum, at a moment when China appears to be considering how best to navigate or exploit transatlantic tensions, to put forward minimum conditions for deeper cooperation. These conditions may not be easy for Beijing to meet – but they are not impossible.

While China will certainly not abandon Moscow, it could take meaningful steps, such as restricting the re-export of dual-use goods to Russia — a difficult but feasible ask. On industrial overcapacity, Beijing might agree to voluntary export price floors. And while China is unlikely to undertake an overhaul of its export control regime any time soon, it could offer the EU greater stability by committing to three-year export licenses for heavy rare earths and other critical materials that it controls, thus offering greater predictability in key supply chains.

Beijing is unlikely to embrace these proposals — but the effort is still worth making. Even if it fails, it could help rally Europe behind a tougher, more unified stance.