Enlargement must adapt to evolving geopolitical realities. Security is no longer a background concern for EU citizens. According to the latest Eurobarometer survey, 66% of Europeans want the EU to play a stronger role in shielding them from global crises and security risks. Defence and security now rank as the leading areas where citizens expect the EU to assert global influence (36%), with economic competitiveness close behind (32%) (1). This shifting sentiment signals a recalibration of public priorities. For EU candidate countries in the Western Balkans, this presents an opportunity to position themselves not merely as beneficiaries of stabilisation efforts, but as active contributors to a more resilient Europe.

Recent visits by HR/VP Kaja Kallas and Commissioner Marta Kos to the Western Balkans, undertaken on separate occasions over the past few months, underscore the EU leadership’s resolve to keep the process afloat. But words alone no longer suffice. This Brief argues that if the EU is serious about enlargement, it must recalibrate its strategy – not only in candidate countries, but also within its own Member States. Public scepticism remains a major obstacle, one that is too often overlooked in favour of a technocratic focus on meeting accession criteria. What is needed now is clarity: a merit-based process that is grounded in democratic values and meets the urgency of today’s security challenges. This message must resonate not only in Brussels, but across Member State capitals.

Despite the doubts, the EU remains the destination

The EU’s trade-off between stability and values over the past few years has weakened the appeal of enlargement. In the Western Balkans, governments tend to use the enlargement process as a political tool, instrumentalising it to extract concessions or deflect responsibility. Meanwhile, Brussels is blamed for stagnation while the region’s political leaders are not held accountable by their domestic constituencies for failing to reform (2). The result? Rising public disillusionment, with many citizens perceiving EU integration as a project that serves elites instead of delivering meaningful transformative change for society as a whole.

The EU’s trade-off between stability and values over the past few years has weakened the appeal of enlargement.

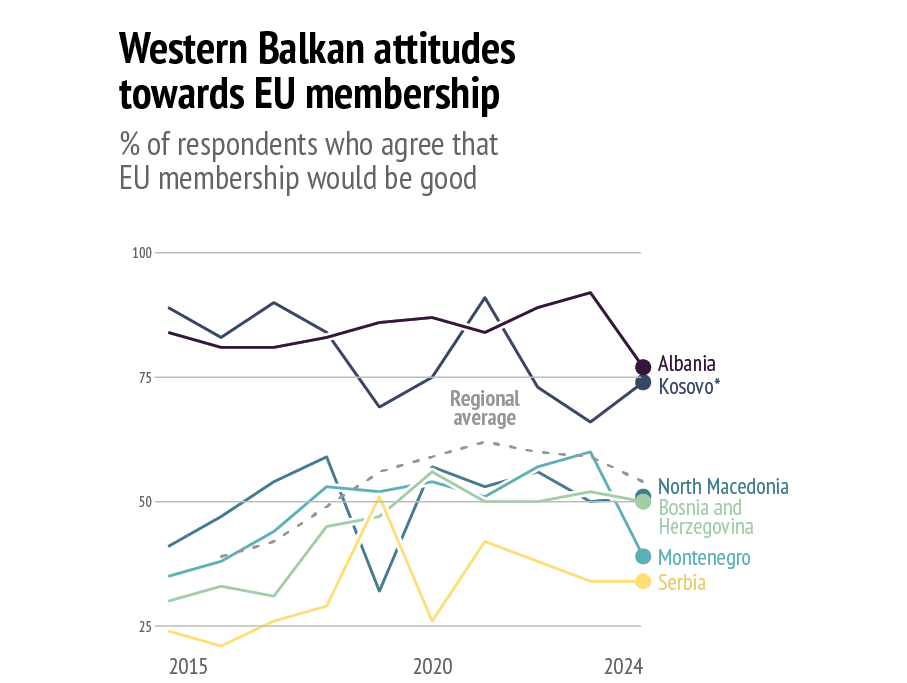

Public support for EU membership across the Western Balkans has remained relatively stable since 2015, although with significant country-to-country disparities (see graph below). These variations largely reflect each country’s internal dynamics, but also growing public impatience with the slow pace of accession. In Bosnia and Herzegovina support has hovered steadily at around 50%, reaching a peak of 56% in 2020. North Macedonia has experienced notable fluctuations but has generally maintained support levels between 50% and 57% since 2020. Serbia’s trajectory has been more volatile, with support rising from 24% in 2015 to 51% in 2019 before declining to 34% in 2024. Montenegro, meanwhile, saw support drop sharply from 60% in 2023 to just 39% in 2024 (3). In contrast, traditionally strong supporters like Albania and Kosovo have continued to register higher approval rates, although recent shifts are evident: support in Albania declined from 92% in 2023 to 77% in 2024, while in Kosovo it rose from 66% to 74% in the same period.

Data: Balkan Barometer, 2025 / * This designation is without prejudice to positions on status and is in line with UNSCR 1244 and the ICJ opinion on Kosovo Declaration of Independence.

However, while popular support for enlargement at the regional level may not have been very high over the years (peaking at 62% in 2021 and falling to 54% in 2024), outright opposition to enlargement has declined, dropping to 10% in 2024 from a peak of 20% in 2016. This suggests that while optimism may be fading, it has not given way to outright rejection. Instead, citizens appear to be caught in a space of cautious hope or growing indifference. Less convinced, but not entirely disillusioned.

A case in point is the way the EU is increasingly viewed through an economic lens. Over the past decade, according to the Balkan Barometer, economic prosperity has consistently ranked as the foremost perceived benefit of EU membership. While freedom of travel (in 2015 and 2021) and opportunities to study and/or work in the EU (in 2016 and 2017) have occasionally emerged as primary motivations, these too are closely tied to economic aspirations. The message is clear: for many in the Western Balkans, the EU still represents a promise of a better life, even if that promise is stretched thin by an accession process that seems endless. This is also why it remains highly unlikely that citizens in the Western Balkans will entirely turn their backs on the EU. There is no viable alternative. No other actor can match the EU’s economic potential to deliver long-term growth and meaningful integration.

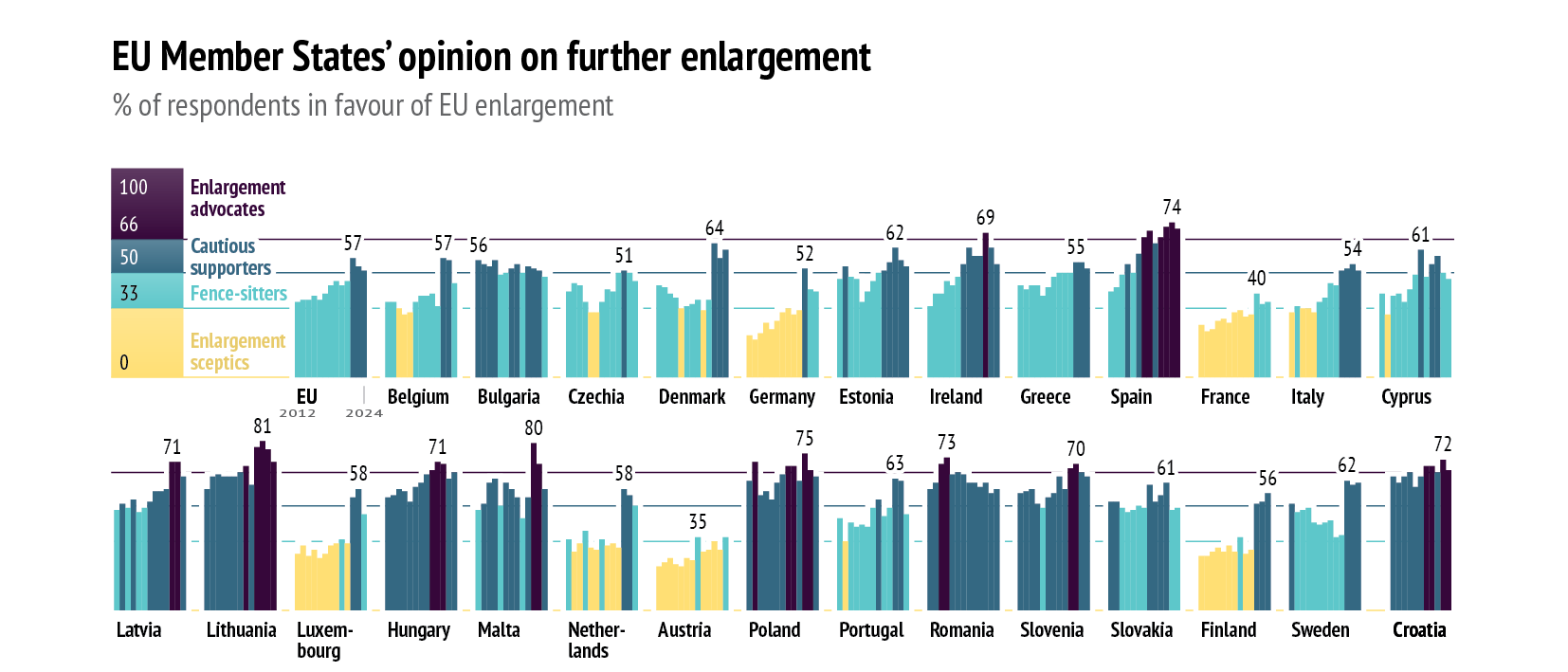

This stands in contrast to the prevailing mood within the Union itself, where public opinion in many Member States has long been sceptical of further enlargement (see diagram on the next page). Over the 2012–2021 period, a clear pattern of consistent scepticism towards EU enlargement emerges, particularly in Western and Northern Europe. Austria stands out as the most persistently sceptical Member State, having been classified as such in nearly every year of the 2012-2021 analysis period, closely followed by Luxembourg, which maintained a similarly firm stance until recent years. France and Germany – two of the EU’s most influential countries when it comes to enlargement – also exhibit prolonged periods of public opposition, with scepticism deeply embedded in national discourse from as early as 2012. The Netherlands and Finland feature frequently as well, indicating a cautious, if not resistant, attitude towards further expansion. While citizens in some countries show fluctuating levels of support, this core group of long-standing sceptics highlights the political and perceptual hurdles that enlargement faces within the Union itself. This matters, as enlargement ultimately requires broad political and societal consensus within the EU. A stronger, more compelling case must therefore be made to policymakers and citizens alike.

Data: Eurostat, EuroBarometer, 2025;

A notable shift in public opinion appears to have occurred in 2022, coinciding with the outbreak of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. Eurobarometer data collected in the summer of that year – just months after the war started – suggested a more favourable attitude to EU enlargement among citizens. It recorded the highest number of enlargement advocates (4) (i.e. Croatia, Hungary, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovenia and Spain). While it cannot be stated definitively that the war caused this change, the timing suggests a strong correlation. In its aftermath, Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova submitted EU membership applications, and both Ukraine and Moldova were granted candidate status in June 2024. This marked a paradigmatic shift in the EU’s approach to its Eastern partners, driven by a renewed sense of geopolitical urgency.

At the same time, a significant group of cautious supporters emerged, with 16 Member States (i.e. Belgium, Bulgaria, Czechia, Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia and Sweden) registering support levels between 51% and 65%. Only one country, France, fell into the category of fence-sitters (34%–50%), while Austria stood alone among the enlargement sceptics (0%–33%). Although the post-2022 period has seen a modest decline in public support for enlargement among Member States, levels remain higher than those recorded before 2022. Notably, in 2024, no country fell into the ‘enlargement sceptics’ category.

The changed security context has likely influenced how citizens across the EU perceive the strategic importance of enlargement. This suggests that framing enlargement through the lens of security – by highlighting how candidate countries could contribute to collective defence and stability – may help reinforce public and political support within the EU. This could include greater cooperation on strengthening the defence industry through the EU’s ReArm Europe Plan/Readiness 2030 initiative, which would bolster Europe’s security and supply resilience. Deeper engagement in CSDP missions, closer alignment with the EU’s foreign and defence policies, and closer collaboration between candidate country experts and EU-supported cyber initiatives would also position the Western Balkans as a frontline buffer against hybrid threats – directly contributing to the EU’s collective resilience.

Reigniting support

Ultimately, enlargement hinges on one thing: trust. Without mutual trust, there is no credible path forward. EU leaders should frameenlargement as a strategic investment in the EU’s stability and resilience.

Tying security to democracy

If the EU is serious about advancing enlargement, it should treat security and democracy as mutually reinforcing priorities. A credible and sustainable enlargement process depends equally on the resilience of democratic institutions and on regional stability. Structural vulnerabilities, weak rule of law, and fragile institutions in candidate countries not only hinder progress but also expose both the region and the EU to exploitation by organised crime, trafficking networks and malign influence. Strengthening democratic governance and the rule of law is not optional – it is essential for ensuring long-term security. The EU should therefore prioritise both dimensions in parallel.

Reframing the enlargement narrative

The EU needs to rethink how it discusses and approaches enlargement, both in candidate countries and within the Union itself. For candidate countries, it should be framed in terms of tangible, everyday benefits that resonate with citizens. This involves bringing the process closer to people’s lives, and demonstrating how it affects communities and individual well-being. One effective approach is using cultural diplomacy to translate enlargement into familiar and accessible terms – through arts, sports, literature, science, music, business, and beyond – so that people can connect with the EU on a human level. Leaders on both sides should work to transform high-level political messages into policies that engage local communities, helping citizens in both the EU and candidate countries understand the real-life benefits of integration.

At the same time, the EU should actively reach out to Member State governments, parliaments, and publics by highlighting how candidate countries contribute economically, socially and strategically. Candidate countries should also step up – taking the initiative to advocate for their own accession through sustained diplomatic outreach in EU capitals. Such active diplomacy should begin early in the process and well before accession talks conclude, to avoid last-minute resistance rooted in a lack of public understanding or political will.

Opening enlargement to domestic debate

To shift public opinion, enlargement must become a topic in domestic political discussions across Member States. The debate on enlargement should be fostered at all levels, reaching beyond traditional supporters to engage all EU capitals. When citizens view enlargement as more than just a political decision, they are more likely to support it. For instance, the introduction of visa-free travel to the Schengen Area was widely celebrated in candidate countries as it helped make EU integration feel more tangible and relevant to everyday life. Municipal councils, youth organisations and academic institutions should host discussions on enlargement’s impact on jobs, security, and culture. Commission Representations in Member States and EP Liaison Offices can organise more events on enlargement and provide information to stimulate these conversations. Academic institutions like the College of Europe in Bruges, Warsaw and Tirana, among others can host more workshops on EU integration. This is a timely effort, as it takes time and consistency to embed such dialogue into public consciousness.

Sharing responsibility while ensuring accountability

The EU cannot shoulder the enlargement process alone. It must be transparent, predictable, and supportive of reform efforts. But ultimately, it is the job of candidate country governments to drive the accession process forward – and to take full responsibility when they fail to do so. The EU should continue using the Reform Agendas strategically: rewarding progress but suspending financial support when reforms stall. This conditionality paradigm strengthens accountability, making clear that governments must answer not only to Brussels, but to their own citizens. Building a stronger government–citizen nexus is essential to prevent the EU from being blamed for domestic shortcomings and to foster transparency and responsibility within aspiring Member States.

References

* The author would like to thank EUISS trainee Marlene Marx for her research assistance.

- 1 For more see Eurobarometer, European Parliament, Winter Survey 2025, Parlemeter EB 103.1.

- 2 See Bechev, D., ‘Can EU enlargement work ?’, Carnegie Endowment, 20 June 2024.

- 3 These findings are based on Balkan Barometer data and may not fully align with national-level surveys, which may reflect differing trends due to methodology, timing, or sample variation.

- 4 The four categories (enlargement sceptics, fence-sitters, cautious supporters, and enlargement advocates) have been devised by the author as a simplified but illustrative framework for interpreting varying levels of public support for EU enlargement. Based on percentage ranges, these analytical categories are intended to guide analysis, not to suggest rigid or universally accepted classifications.