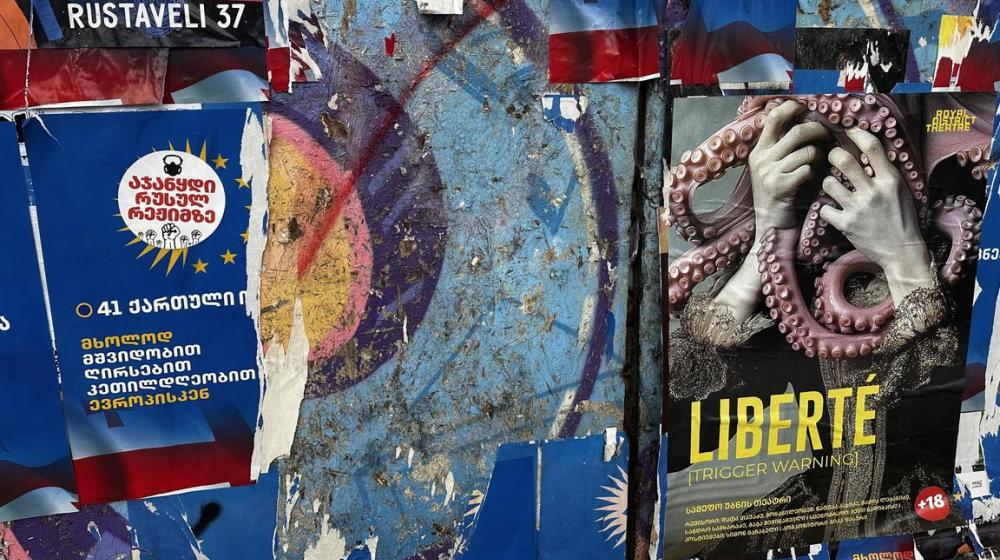

Last week, Georgia's new law on foreign agents took effect. Amidst worries that the government will apply it arbitrarily to further supress dissent in view of the ongoing crackdown on political opposition, NGOs and independent media, HR/VP Kaja Kallas and the Commissioner for Enlargement Marta Kos issued a joint statement on 31 May. They warned that this and other repressive measures pose a serious threat to Georgian democracy, and reaffirmed that Georgia's path to EU membership is now effectively blocked.

Sadly, the shift towards authoritarianism accelerated after the October 2024 parliamentary elections, reflecting the trajectory anticipated in a Brief published by the EUISS in the aftermath of the contested poll.

Relations with the EU will not return to normal as long as Georgia continues on its current political path.

A small political and business elite is actively driving Georgia's authoritarian drift, under the influence of the country's dominant powerbroker: the tycoon and former prime minister Bidzina Ivanishvili.

This elite appears to operate under a number of illusions. Dispelling these illusions is essential if there is to be the slightest chance that the Georgian Dream government might reconsider its course before being forced to do so by a major crisis.

A reality check

First, relations with the EU will not return to normal as long as Georgia continues on its current political path. As a candidate state, Georgia is subject to much stricter scrutiny, and the EU’s tolerance for authoritarian tendencies is much lower vis-a-vis prospective members than for other states.

Second, this means that it is pointless to expect the EU to initiate a 'normalisation' of relations or resume Georgia's accession process under current conditions. While the Georgian government has friends in the EU who have successfully opposed more punitive responses by the bloc, opening accession chapters requires unanimity – which will be impossible to achieve as long as the government pursues its current policies and continues to direct hostile rhetoric against the EU. Even a more limited rapprochement would require support from a critical mass of Member States, which is currently lacking.

Georgia can join the EU – but it will need to want to do so badly enough.

The reason for that has a lot to do with the third illusion: that Georgia really matters to the EU. This is perhaps the most painful one to dispel, as it is shared by many Georgians who continue, at the risk of prosecution, to bravely stand up against the government. While the EU has indeed renewed its focus on Eastern enlargement, in a world increasingly shaped by geopolitical contestation and pragmatic calculations, Georgia has little to offer in strategic terms. While bringing Georgia into the fold might enhance Black Sea security, the latter objective is not contingent on its membership. Despite bold visions of the 'Middle Corridor', the tangible benefits of enhanced connectivity cutting through the Eurasian heartland remain hazy and remote. Pipelines traversing Georgia are useful to the EU, as they transport Azerbaijani gas and oil. However, while these resources are valuable (amounting to 4 % of the bloc's gas imports in 2024), they are not irreplaceable. Their importance is moreover likely to decline over time if the green transition goes forward. Georgia can join the EU – but it will need to want to do so badly enough.

The third illusion is related to the fourth one – it concerns the belief that Georgia possesses greater geopolitical leverage than it actually does. The Georgian Dream government appears to believe that it can cement recent economic gains (the Georgian economy grew by 9.5 % in 2024) through a form of ad hoc, opportunistic geopolitics – striking deals with several external powers at once, ranging from Russia to China, Türkiye and the Gulf states. But as shrewd as the government may be, it runs the risk of entangling Georgia in dependencies on actors known for their ruthlessness, and turning the country (once again) into a geopolitical battleground. In such a scenario, neither the government, nor the people of Georgia stand to benefit. As much as the government would like it to be, Georgia is no Azerbaijan.

Fifth, Georgian Dream should not assume that the EU itself will undergo a transformation that will pave the way towards embracing illiberal Georgia as a member. Irrespective of one’s political perspective, from a purely analytical point of view, it is clear that the sheer scale of change required – both within Member States' domestic politics and in the EU's institutional frameworks – for this to happen is inconceivable in the foreseeable future. A year from now, Georgian Dream may have a few more friends in the EU; or it may have a few less. That is about the extent of change it can expect a decade from now as well.

In Georgia, history is not on the authoritarians’ side – as many have learned, even in the not-so-distant past.

Sixth, even if somehow the EU were to change and become willing to take in Georgia in its current political state, there is no way it could join the EU in three years time as the Georgian Dream government has claimed. Georgia has indeed made commendable progress towards drawing closer to the EU – much of it under the leadership of Georgian Dream. But even if the Georgian Dream government's current policies did not represent a serious backslide or undermine the state institutions painstakingly built and staffed by competent public servants over the past two decades, the timeframe would still be utterly unrealistic.

The last, seventh illusion is that the creeping slide towards authoritarianism can extinguish freedom that the Georgian people have repeatedly demonstrated the resolve to fight for. In Georgia, history is not on the authoritarians’ side – as many have learned, even in the not-so-distant past.

The EU should not give up on Georgia

Those engaging with Georgia's leadership should make these points clear, while also stepping up support for democratic freedoms, an open civil society and local communities under pressure.

The EU must not give up on the people who overwhelmingly aspire to be part of the European family of nations and to be governed, in Europe’s best traditions, by the principles of liberty and the rule of law.

If it did so, it would be giving up on itself.