Russia’s aggressive geopolitics, deepening local fragilities and recent policy reversals by the US administration all make it imperative for the EU to enhance its efforts to build resilience as its ‘overriding policy objective’(1) in its Eastern neighbourhood. Yet, foreign aid resources are becoming scarcer not only due to recently announced USAID cuts but also to the EU redirecting public funds to other areas, notably armaments. Therefore, the EU needs to operate with greater efficiency, guided by an updated understanding of resilience that underscores its transformative, whole-of-system and community dimensions. This Brief explores how this approach can be applied in three countries of the Eastern neighbourhood – specifically Moldova, Georgia and Armenia.

Funding strains

While the impact of USAID cuts on resilience efforts in Moldova, Georgia and Armenia is not catastrophic – given that US contributions account for less than 20% of programmed assistance in each country(2) – the EU still faces serious constraints. The Commission’s currently limited resources, along with anticipated further cuts in foreign aid from Member States, constrain the EU’s options when trying to fill critical gaps. To ensure that partner countries remain resilient and avoid creating a vacuum in development assistance, the EU must make strategic choices anchored in this new reality. Otherwise, alternative providers like China or Türkiye could exploit these gaps, leading to new or deepened dependencies that could potentially be instrumentalised.

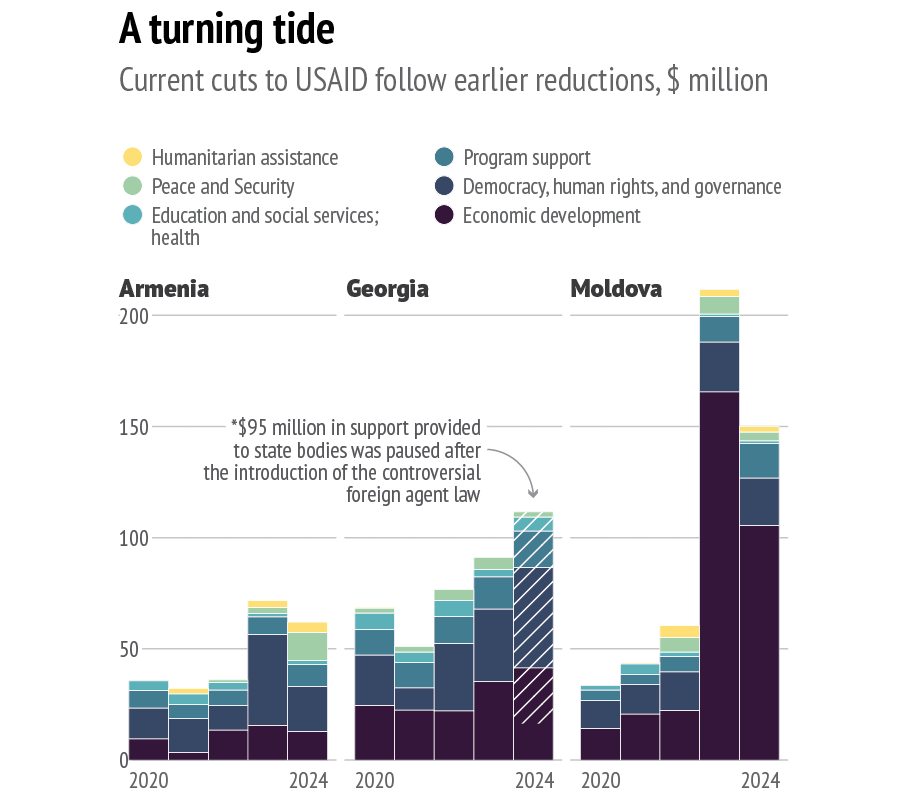

USAID funding for projects in the Eastern neighbourhood declined already in 2024, falling from $16.8 billion in 2023 to $6.4 billion (-62 %)(3). This drop was largely accounted for by reduced USAID financing for Ukraine. Meanwhile, a planned increase in obligations to Georgia (to $111 million) was shelved after $95 million in support to state bodies was paused due to the government’s introduction of the controversial foreign agent law. In Moldova, funding obligations dropped from $211 million (2023) to $150 million (2024). Resources channelled to energy projects such as the third interconnector with Romania between the Strășeni and Gutinaș power stations increased by $50 million, but funding for government and civil society dropped by $110 million (more than 80%) in the same period. In Armenia, resources provided to government and civil society decreased by $10 million in 2024 (50%)(4).

Data: ForeignAssistance.gov, 2025

A wide range of projects have been affected, spanning local economic and agricultural development, the promotion of inclusivity and minority rights, education and workforce training, and efforts to enhance shock resilience. Initiatives aimed at reducing strategic dependencies – such as Moldova’s indirect reliance on gas imports or Armenia’s dependence on wheat and other staple imports – as well as those exploring future connectivity opportunities, have also been impacted. Funding was also withdrawn from three major regional programmes related to countering disinformation: the Georgia Information Integrity Program (obligations worth $9.3 million), the Media Program in Armenia (a $7.5 million project co-funded with the UK) and Moldova’s MEDIA-M initiative ($11 million).

The EU and Member States have been providing significantly more financial assistance than the US to the Eastern partners – as well as worldwide(5). However, major donors including France, Germany, Sweden and Finland are also reducing their foreign aid commitments(6), while more cuts are anticipated as defence expenditures are set to rise in the coming years. The Commission has little wiggle room and available funds to address immediate gaps. The overall allocations in the next multiannual financial framework (2028-2034), preparations for which are now underway, are likely to be less generous due to shifting funding priorities. Encouraging local beneficiaries to better align their efforts and diversify their funding streams may yield some efficiency gains, but these are unlikely to offset the cumulative losses.

Rethinking resilience

The EU must maximise the impact of its investment in reforms through clear prioritisation and, where feasible, targeted increases in funding. A stable and prosperous Eastern neighbourhood that is as closely integrated as possible remains a core strategic interest for the EU. Resilience can continue to orient efforts to that end and facilitate a more strategic approach – but only if the concept gets a critical update.

First, the original ambition of the concept – to drive positive change rather than just defend against adversity – needs to be restored. Resilience was firmly embedded in EU practice through the 2016 EU Global Strategy, particularly in the context of its integrated approach to conflict. However, during the Covid pandemic and as the external security environment grew more hostile, it turned more defensive and introverted. This trend should be reversed. Resilience as transformation should not just be about endurance or the capacity to withstand adversity and shocks. It must also encompass adaptation and recovery – not merely coping with change but actively shaping it in line with a collectively shared vision of a better future. This vision should be grounded in core values, including a commitment to freedom, and in common ideas about how society should be organised around those values.

Second, resilience cannot be a trumpet call to tackle ‘everything, everywhere and all at once’. But its whole-of-system nature needs to be (re-)emphasised. At present resilience is often compartmentalised into distinct domains – political, economic, societal, environmental or digital – whereas it should be understood as arising from the dynamic interplay between all of these simultaneously. Understanding how these interactions shape outcomes is crucial to avoid reducing resilience to narrow objectives, such as securing electoral wins for favoured parties, while overlooking the critical task of building independent, efficient institutions and strong, pluralistic political communities. It is important also to avoid ad hoc, unplanned cuts which in complex systems may have far-reaching and unforeseen consequences.

Third, resilience should be framed in terms of community. This means placing greater emphasis on empowering local communities (rather than individuals) to cope with economic or environmental crises. It also involves fostering inclusive, deliberative platforms where community needs can be openly discussed. Locally-led development not only improves livelihoods but also helps reduce socioeconomic disparities that fracture political communities, heightening their vulnerability to authoritarianism and foreign malign influence.

Furthermore, a renewed emphasis on community within the updated concept of resilience should continue to address negative, weaponisable dependencies. This includes reliance on critical imports of energy or food staples from Russia but also, notably in Georgia, the dependencies of local communities on a captured state and its clientelist networks. It should equally highlight the importance of cultivating positive relations with trustworthy ‘others’ from the local level up, and of fostering a shared commitment to common institutions and democratic politics. This should manifest also in promoting narratives of a common future(7). Storytelling is often deployed to incite division and enmity. Within an updated concept of resilience, it should be harnessed to overcome prejudice and help build peaceful societies(8) held together by a common commitment to social solidarity and environmental responsibility(9).

Finally, the community dimension of resilience should highlight its collaborative nature as a shared endeavour between the EU and its Eastern partners. Resilience is a never-finished project. It requires continuous learning and adaptation. Many of the challenges faced by the EU and its Eastern partners – whether stemming from Moscow’s hybrid tactics, contested democratic politics or climate change – are similar in nature. They can be addressed most effectively by drawing on the diverse knowledge, experience and skills of all involved, while remaining attentive to the specific priorities and contexts of each country.

Focus on what matters now

The updated concept of resilience should strategically orient the EU’s efforts and resources to what matters most. The challenges each Eastern neighbourhood country faces may be similar, but they manifest differently in each context, making some issues more urgent than others. This can be illustrated by zooming in on three countries in the region – Moldova, Georgia and Armenia. What resilience challenges are most pressing here, and how can they best be addressed in light of present and future anticipated foreign aid cuts?

Moldova. Russia’s blatant interference in the recent referendum and presidential election (2024) make it imperative to prevent manipulation of the forthcoming parliamentary vote. The EU has already shown that it can act with resolve, as demonstrated by the immediate relief provided in January 2025 to offset higher electricity costs arising from alternative imports. This support came in response to Moscow’s renewed weaponisation of Moldova’s energy dependence – specifically its continued reliance on electricity (70%) imported from the breakaway Transnistria region where it is produced by burning Russian gas(10). But the new Comprehensive Strategy agreed by the European Commission and Moldova is less specific on the measures needed to ensure the country’s long-term energy independence. More concrete steps are required, also in view of the uncertainty regarding continued US funding for the Moldova Connected initiative, which includes the construction of a third interconnector with Romania as well as the development of a battery energy storage system (BESS). Moreover, in line with the updated concept of resilience proposed in this Brief, the EU should offer more institutional support over the longer term to the Central Electoral Commission, the Centre for Strategic Communication and Countering Disinformation, and the National Agency for Cyber Security to help safeguard electoral integrity. It should also take further steps in the spirit of the Security and Defence Partnership (2024) – in particular through enhanced consultations on foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI) that can be of mutual benefit. At the same time, it should strategically incentivise and strengthen government efforts to tackle deeper structural issues such as corruption, social fragmentation and the alienation of certain communities – factors that continue to undermine Moldova’s national cohesion. Building trust is a necessary precondition for the future reintegration of Transnistria, in addition to substantial future investment. While many in Transnistria remain distrustful of Chisinau, there is also growing awareness that the region is being used as a pawn in Moscow’s geopolitical gamesmanship. Moldova’s slow economic recovery after the last recession (the economy contracted by 5% in 2022) further requires addressing structural challenges to competitiveness and welfare. These include a persistent lack of investment (notwithstanding a significant increase in FDI provided by the EU over the last decade), inadequate infrastructure and workforce shortages(11).

Georgia. Immediate challenges to resilience are different in Georgia where a process of state capture is well under way. The ruling party is intensifying its efforts to remove the remaining obstacles to its uncontested power, both within the state apparatus and in civil society and independent media. The EU should not only ‘ring-fence’ funding for civil society and free media but also speed up disbursement as much as possible before new, more restrictive ‘foreign agent’ legislation comes into force. It should furthermore strengthen protective measures, including through improved access to legal aid. The EU should also support local communities to reduce their dependence on the captured state. More independent local communities, with reliable and adaptive local support networks, will be better able to resist authoritarian pressures from the centre. The narrative of a common future in the EU must be accompanied by a clear message: the model of government currently established by Georgian Dream is fundamentally incompatible with European values. Moreover, the EU should step up efforts to expose the government’s hypocrisy in claiming to restore sovereign independence by backtracking on the EU accession process. In effect, this only serves to consolidate its authoritarian rule and drive Georgia closer to the Kremlin and other illiberal powers who are unlikely to display much respect for the country’s sovereignty.

Armenia. Armenia’s economic dependence on Russia remains deeply entrenched and weaponisable, exacerbated by the unresolved conflict with Azerbaijan and the continued closure of the borders with Türkiye. The EU’s pledge to allocate €270 million through the Resilience and Growth Plan (2024-2027) to support Armenian businesses and industries is a welcome step towards reducing this dependence. However, without resolving the conflict and developing inclusive connectivity that benefits all – including Armenia – by facilitating trade flows with Europe and the Middle East, the country’s resilience will remain fragile. Turning the tide will require all states in the South Caucasus to embrace a shared vision of an open and peaceful region free from conflict and hegemonic ambitions. The EU’s priorities for Armenia should be to foster a strong independent media and civil society to counter Russia’s attempts to control the information space – a domain particularly affected by recent USAID cuts. The EU should focus on strengthening the government’s institutional capacity, including to plan and manage large-scale projects, and step in to replace US support for Armenia’s border management capacity building. It should resist pressure to prematurely terminate its own monitoring mission (EUMA), which has played a key role in conflict prevention. Finally, it should support a comprehensive approach to solar energy production to help Armenia build an independent domestic power supply.

References

* The author would like to thank Carole-Louise Ashby, EUISS trainee, for her invaluable research assistance.

- 1 Joint declaration of the Eastern Partnership summit, Brussels, 15 December 2021

- 2 OECD Data Explorer

- 3 The total appropriations (co-)managed by USAID decreased from $42 billion in FY2023 to $35 billion in FY2024. ‘U.S. Agency for International Development: An overview,’ Congressional Research Service, 14 March 2025

- 4 ForeignAssistance.gov (accessed on 24 March 2023).

- 5 OECD Data Explorer; Worldwide, Team Europe disbursed 41 % of the total ODA in 2023, compared to 20.3 % by the US.

- 6 EEAS, ‘A shared vision, common action: A stronger Europe’, EU Global Strategy, 2016.

- 7 Korosteleva, E., Nurturing resilience in Central Eurasia, Oxford University Press, forthcoming.

- 8 Sparre, C. and Wilks, J., ‘Storytelling: A tool for change‘, SIPRI, 2024

- 9 Connolly, W., ‘The “new materialism” and the fragility of things‘, Millenium, Vol. 41, No 3, 2013.

- 10 The Commission first released €30 million in January, with the foreseen additional €100 million disbursed by April. The EU previously provided €240 million in direct budget support to Moldova’s energy system between 2021 and 2024.

- 11 Fanyan, H., Petrosyan, A. and Abrahamyan, M., ‘Increasing the economic resilience of Armenia,’ CASE, 2024.