To make policy is to think about the future – usually trying to shape it for the better. In policy, as much as any part of our lives, our thinking is strongly influenced by our perception of time, yet paradoxically this perception of time is usually unconscious and unquestioned.1 Policy experts and decision-makers are futures thinkers whether they realise it or not. Yet like all humans, they tend to rely largely on a set of familiar modes of thinking when it comes to preparing for the future – modes of thinking that are instinctive, intuitive or institutionalised.

No one way of thinking about the future is necessarily better than another, but all of them are limited, and leave some things unchallenged or implicit. As a result, sticking to only one approach means missing potentially valuable insights that could be gained by using other perspectives. Of course there is no guarantee that learning these lessons will result in perfect preparedness for what lies ahead, but if there is great potential in ‘out-of-the-box thinking’, then it helps to better understand and challenge what is boxing our thinking in.

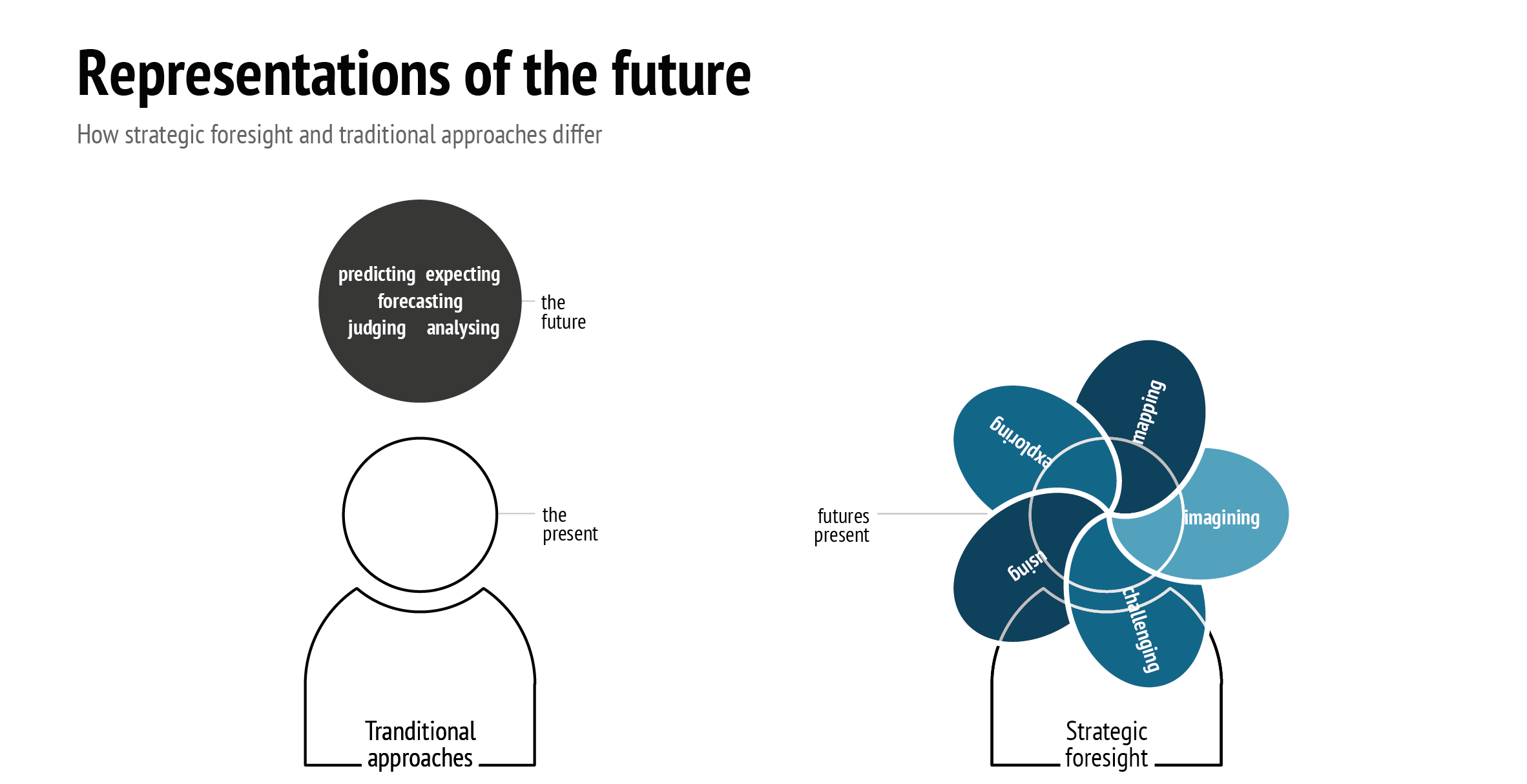

This Brief, and the strategic foresight approaches it outlines, are therefore not intended to introduce thinking about the future where it was absent, but rather to challenge, discipline, and guide the futures thinking already taking place. It will take the reader through five of the ways in which relying only on conventional ways of thinking about the future may be keeping them from seeing a lot more. It will seek to answer the question: how can the discipline of strategic foresight make a positive contribution to the field of foreign policy?

This Brief is not an instruction manual or how-to guide on methodologies of strategic foresight. Less still is it able to help the reader to better predict the future, or make the right call on what to prepare for. Instead it intends to show how thinking differently about the future can help to increase our awareness and knowledge in the present and what it means in terms of the decisions we make.

Probable or useful? The ‘right’ future(s) to learn from

Forecasting based on past evidence can be very useful. Forecasts allow us to better understand trends by analysing the factors underlying them, and envisaging trajectories that they could follow. However forecasting also has limitations. Many high-quality forecasts have turned out to contain errors. Forecasts may use probability or multiple projections to estimate the range of likelihood of an outcome, but this is often misinterpreted, and people may assume the middle of a range of outcomes is the ‘real future’, or discount improbable outcomes as not worth considering.2 Furthermore some future developments simply cannot be forecast because too little is known about the relevant factors.3

While evidence is vital for conclusions about what happened in the past, there can never be complete evidence about the future. Innumerable things will come about in the future which will be truly unprecedented and for which there is little or no hard proof today. The future is emergent and at best only indirectly observable through what is occurring in the present. Ignoring developments with only weak evidence means missing developments from which we could have learned in advance. One such case is the effect of disruptive technology on the defence and security domain. It is not sufficient to refer to previous technological advances to understand, for example, how artificial intelligence may enable transformations not just in accomplishing today’s tasks within today’s frameworks, but in the way defence forces are organised and operate.4

The future is emergent and at best only indirectly observable through what is occurring in the present.

Indications about the future can also be contrasting or even conflicting. In these cases it is common for people without a background in strategic foresight to suggest that the ‘real future’ will ‘probably be a combination’ of diverging alternative outcomes under consideration. This may be true but the statement defeats the purpose of considering alternatives in the first place. 'We consider the future to be fictional and useful rather than factual and truthful; so it is these fictions that need to be modelled, not “reality.”'5 There is little to be gained from correctly predicting the future if doing so does not enable us to take wiser actions today – and taking wiser actions today does not depend on correctly predicting the future. Taking wiser actions today instead depends on how much we challenge our ideas of the future.

Using the past as a guide is an understandable way to try to prepare for the future. Given that the future is inherently and always uncharted territory, it is intuitive that humans would want to refer to something familiar. In foreign policy in particular, theories and mental models of international relations help to explain the system – and are often used (implicitly or explicitly) to support policy decisions. Theories of international relations may be very appealing for their coherence and explanatory power, however understanding the past does not mean understanding the future. Indeed, scholars of international relations may even use the word ‘prediction’ with reference to their theories’ ability to correctly infer past phenomena, rather than provide forecasts for policymakers to respond to.6 One proposed response is to make even more future predictions to test the validity of theories and critically evaluate assumptions.7 However if predictions are mainly useful for testing our mental models of the past, rather than preparing for disruptions in the future, then making predictions does not help us take better actions in the present; it only lets us prepare to use hindsight at a later date and possibly learn from the past.

We do not need to wait for the future to pass us by and leave us with hindsight; policymaking should adopt an approach that enables it to take action in the present: foresight. This means letting go of seeking a single most probable future, and turning attention to multiple surprising and significant futures that test our mental models ahead of time. Strategic foresight does not seek to determine which future outcomes will come true. But it also does not base its analysis on fanciful conjecture. Instead the task is to assess which plausible future outcomes can be used and learned from.8 To do that, we need to consider what ideas we are not already attending to (the surprising ones), and what ideas would matter most to our organisation's way of working (the significant ones). The standard by which an idea about the future should be judged is therefore not probability but rather the degree of surprise and significance.

This conception of the future in terms of multiple alternatives was born out of necessity in foreign policy before moving into other fields. Recognising the fundamentally different and unpredictable nature of international relations after 1945, analysts at RAND Corporation used the uncertainty to create multiple alternative contexts – scenarios – in which to test strategies and see how they might fare. This use of multiple futures to provide ‘ersatz experience’9 allowed strategists to go beyond merely attempting to predict and respond to a single future, and to better understand the potential success of their actions in varying conditions.

Events or context? Dramatic events and the worlds they inhabit

Consider any of the most pivotal events in history (the World Wars, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the coronavirus pandemic, any revolution, war or invention): none of them can be explained without an understanding of the context – the zeitgeist, the paradigms – that prevailed at the time. Take any of the most impactful eras of history (the Cold War, the Golden Age, the Enlightenment): none of them can be explained without an understanding of the events that initiated, sustained or ended them. In any good explanation of the past, analysis always combines elements of action (sequential one-off occurrences) with elements of context (ongoing states of being that paint a picture). The interplay between events and context is complex and we cannot hope to get an understanding of what happened without considering both together.

“History is not just one thing after another”,10 and nor is the future: it is a combination of events and context. Yet in spite of this logic, discussions about the future usually concern only new events, not new contexts. Compared with context, it is perhaps easier to imagine and describe a future event, assess its probability, and later test its correctness.11 But it is vital that we understand that context in the future can and will be different to that of today. There is much more to be learned by thinking about the conditions in which we might be operating for extended periods of the future than there is to be learned from events which come and go.

Likewise, it is clear that certain technologies have indeed catalysed transformations in human civilisation – the printing press, the postage stamp, and the internet being some of the clearest examples. However it was not possible to predict the emergence of these technologies, the form they would take, or how exactly they would transform their societies. None of these important technologies would have achieved widespread use without a society that had a use for them. None of the important developments that followed were inherent in the technologies themselves or in their originally intended applications. They all arose from the ways in which societies made use of the technologies in later years.

Studying an event or new technology which might materialise is a potentially useful yet highly specific field of knowledge to explore and use to develop ideas about the future. Taken in isolation, it only reveals the immediate implications of the event or technology for our own organisation and times, potentially missing the broader social, economic, environmental or political changes in circumstances that might precede or follow the emergence of that event or technology. Without that additional analysis and interpretation (often referred to as ‘sense-making’), studying an event or technology on its own does not support us to imagine ourselves in a very different future – or develop strategies to succeed in it.

One example of the effective use of context rather than events is in the future scenarios project developed by the Dutch ministry of defence, whose scenarios are built in the tradition of NATO’s Multiple Futures and the US National Intelligence Council’s Global Trends projects, as well as work of the German Zentrum für Transformation der Bundeswehr.12 The scenarios focus on which actors matter most, and how they relate to one another – contextual factors which could determine the emergence, significance, and consequences of events. These scenarios, and subsequent foresight processes, have been used in the Dutch government among others to inform policy considerations in terms of what is important to focus attention on in the present, and what capabilities to develop ahead of time.13

Complicated or complex? All other things are never equal

In the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, there were multiple sets of uncertainties. There were uncertainties surrounding the behaviour of the virus itself (its ability to cause disease in different people, the various routes of transmission, etc.); uncertainties surrounding how the pandemic would unfold (death rate, reproduction rate, etc.); and uncertainties about what would happen next (how many businesses would bounce back fom lockdown losses, how countries’ geopolitical relations would be affected, etc.). On all of these matters, governments sought the best available knowledge and advice.

Yet relatively little attention was given to what ties all the above uncertainties together: the underlying characteristics of societies, different all around the world, which determined the behaviour of the virus, the unfolding of the pandemic, and what would happen next. This broader set of factors concerned matters such as the level of physical contact customary in a given culture, the use of mass transit compared with private vehicles, perceptions of risk, and frequency of intergenerational contact. These uncertainties had to be assumed in advance in any epidemiological model used to inform policy decisions on controlling the pandemic. The tendency to make these assumtions implicitly rather than explicitly may explain why some models proved misleading, and why models designed for use in certain places proved useless in others.

The future is strongly shaped by multiple arrays of factors like those above. Yet too often we treat such complexity as if it was merely complicated. The difference is great. Complicated systems like a phone or a car maybe be difficult to understand but there are fixed rules governing interactions. These rules can be learned through empirical observation and expert analysis to reliably predict how the system will behave and the likely effects of any changes made. Complex systems like a phone conversation or a traffic jam contain multiple interrelated causal relationships, uncertainties, feedback loops, tipping points, emergence, and other effects which make them more than the sum of their parts. There is no reliable set of rules which will always apply, and making changes will not always produce the same effect.

In studying complex policy domains like international relations or an economy we tend to try to separate relationships out and infer rules that govern them, all other things being equal. This principle of ceteris paribus can be beneficial and serves a purpose in understanding the aetiology of phenomena and the relationships between them, but its usefulness is limited to complicated problems which can be empirically observed. Those conditions do not apply in the case of the future, since the future is complex and impossible to empirically observe.14

Humans find it challenging to grasp the future as a tangle of interrelated phenomena which cannot easily be separated. One way of making this complexity manageable is not to reduce the number of variables, but instead to weave them together into narratives. Stories are just as valid as models as a guide to the future, if they help us to understand something enough to take effective action.15 One high-profile example of foresight analysis in the security field which views the future in this way is the National Intelligence Council’s Global Trends report, in which scenarios are used to explore how “[future] events unfold in complex ways for which our brains are not naturally wired.”16 Most readers would be struck by the prescience of the storyline in one of the scenarios about a global pandemic in 2023 which ‘dramatically reduced global travel in an effort to contain the spread of the disease, contributing to the slowing of global trade and decreased productivity’. However from a foresight perspective, what is most valuable is not the success of the analysis in spotting a particular development that came to pass, but the complexity and interconnectedness of multiple phenomena. The use of narrative allows these to be perceived, made sense of, and woven into storylines which can be used to challenge and improve strategy in the present – irrespective of whether any of the predictions actually come to pass.17

Should or might? Solving the future before exploring it

Economic growth, rules-based trade, free markets, European integration, containment: these have all been presented as the objective of at least one institution or school of thought. To supporters of these institutions or schools, discussions of the future and strategy will usually turn quite quickly to how such objectives can be furthered. But in reality, they are more than objectives: they are solutions pursued in response to challenges such as poverty, war and geopolitical competition. In a world of complex problems, proven approaches cannot be relied on to work every time; what worked last time might not work the next. The risk is that organisations find themselves in new contexts where their trusted models and approaches to deal with challenges and grasp opportunities stop performing as they used to. Yet in many futures dialogues, participants will advocate addressing an imagined future challenge or opportunity with more of the same approach their organisation is already advocating.

Policy is in many respects a problem-solving discipline. By trying to remedy failure or optimise success, we are seeking to find a solution. As a result, when discussing the future, policy experts tend to switch gear immediately upon identifying a phenomenon, moving from observing it to attempting to solve it. However this mode of thinking can divert attention away from another: exploration. Problems may not be how they appear, and by switching to problem-solving mode, we leave observing mode behind and risk missing out on many complex and interconnected factors that may also be of great relevance. This mode of thinking is analogous to proceeding forward down what seems like the best road to a destination without first charting the territory and exploring different routes that may offer a smoother or more efficient journey.

A similar difficulty applies when considering which problems we seek to solve. Most problems in policy are addressable but not solvable. They can be characterised as ‘wicked problems’ because they have innumerable causes, are tough to describe, and do not have a right answer; attempting to tackle wicked problems using conventional strategies, as if they were merely difficult problems, not only risks failure but could even make the situation worse.18 The security field is beset with wicked problems, concerning virtually every major issue – terrorism, cyber threats, natural disasters, and inter- and intra-state conflict to name but a few.

The future does not care if disruptions come at great expense, confusion, or embarrassment.

It is also important to recognise that while we believe in the power of policy to change the future, it is not omnipotent. Like any organisation, policy institutions must discipline their conversations to make the distinction between external developments beyond their control and the limited ability of their own actions to shape them. “Perhaps the most important insight of complexity is that policymakers should stop pretending that an economy can be controlled.”19

Problem-solving is not inherently bad, but it should not be allowed to crowd out problem-exploring. During policy dialogue, it is important to give adequate time to observing a situation without judgement, understanding the relevant factors and their linkages, and speculating on the multiple different ways in which the future could develop. Strategic foresight methods such as scenario planning and megatrends analysis are ways to create an artificial future world which can be explored, and subsequently different solutions tried out and rehearsed ahead of time. Doing so will not necessarily lead to the ‘right solutions’, but by considering a fuller picture of problems, we can hope that our solutions will take more relevant factors into account and hence be better informed.

Official expectations or anticipations? Unusual business as usual

The coronavirus pandemic was not unforeseen. All of the factors which led to the emergence and spread of the novel virus were known and studied well in advance;20 high-profile and respected experts warned of humanity’s lack of preparedness for an outbreak; and numerous countries had national risk registries and assessments which accounted for the possibility of such a situation developing. Yet in declaring the disease a pandemic, the World Health Organisation (WHO) warned of ‘alarming levels of inaction’ in spite of clear knowledge and advice on what countries needed to do.21 Likewise, it is widely accepted that mitigating the climate crisis and dealing with its consequences will require radical changes in policy and strategy, well beyond the actions of most major organisations and governments today. Both coronavirus and the climate crisis are cases of emerging futures from which a great deal can be learned today.22 A failure to grasp emerging futures proved fatal to makers of traditional mobile phones and film cameras who failed to adapt to their disrupted contexts. So why do organisations not change course, even in the face of strong indications that their current actions are inadequate?

A sense of future is always implicit in our actions, even when we do not realise it. In the absence of conscious foresight, that sense of future is usually ‘business as usual’ — assumptions and expectations that we can continue in the same way as at present and still succeed or at least cope. Such untested assumptions and expectations may be so deeply embedded in an organisation’s actions that its decision-makers are not even aware that they exist until it is too late.

There are also multiple social and institutional factors that protect the incumbency of business as usual. Unorthodox thinkers who tell an organisation that it needs to radically rethink its understanding of a complex issue or admit that it was doing the wrong thing all along rarely make themselves popular. Some may experience groupthink and moderate their views; some may face censorship; others may censor themselves. Sometimes the preservation of business as usual is in the interests of a powerful individual or group. As a result, foresight work is often used to justify the dominant strategy rather than to challenge it. But that does not make controversial ideas about the future any less useful.

The word ‘expectation’ has two meanings in English: the first refers to beliefs about what will happen (anticipation); the second refers to requirements to fulfil an obligation. In this sense, the expected future is an anticipatory phenomenon but also an institutional phenomenon, something that two writers on the subject refer to as the ‘official future’.23 When our organisations expect us to expect something, they are furnishing an otherwise open future with ideas of today – a process which has even been described as ‘colonising the future’.24 By expecting people to expect an approved, official version of the future, organisations fail to make the most of their diverse knowledge, and potentially miss untold opportunities and face needless difficulties. The future does not care if disruptions come at great expense, confusion, or embarrassment to an organisation, but the staff of the organisation do. When it fails to materialise, the expected future is not only a failure of anticipation on an individual level,25 but a failure of cognition on a collective level.

To address these missed opportunities, organisations should make a virtue of the uncertain, undeveloped nature of the future to avoid groupthink and promote a diversity of ideas – including those which imply weaknesses in the organisation’s current way of thinking and strategising. This has been one of the main benefits of scenarios in defence planning in successive US administrations according to RAND Corporation. In a review of force planning scenarios over time, it found that “a portfolio of scenarios that includes a wider range of plausible but stressing scenarios is more likely to yield more useful information about risks, gaps, and mitigation measures than a smaller and less stressing set, and that testing the forces against more combinations of scenarios and scenario variations is better than testing it against only a few.”26

Conclusion

People often perceive the future as being in another place at another time. This notion that thinking about the future involves ‘looking ahead’ (and taking our eyes off the present) leads to the misconception that the current situation is so uncertain or urgent that there is no time to think about the future. This is really a false dilemma. The future needs to be demystified: it is not a remote entity that is separate from the present, just waiting to be found. In fact it does not really exist anywhere other than in the present. The only futures we can really anticipate and learn from are the ones we imagine right now!

What does this mean concretely in policymaking? It is not enough simply to use foresight as an alternative ‘method’ to identify the ‘right things’ to think about in the future and then factor them into the traditional policymaking process. ‘Strategic foresight doesn’t help us figure out what to think about the future. It helps us figure out how to think about it.’27 Strategic foresight is a way of thinking and working – not just a one-off process or event, but a long-term shift in mindset.

Strategic foresight does not view the future as a single, objective, knowable entity; therefore it cannot be passively studied as if it were. Multiple ideas about the future require dialogue for a learning process with useful implications for action. The considerations presented in this Brief offer a starting point for readers to pause and take time to use the future today. Strategic foresight practitioners can help organisations take this further by helping to embed the practice in their decision-making.

By recognising that the future is already being formed all around us, we can ‘unbox’ it and understand it better now. This helps us pay attention to surprising and significant developments which seem improbable but from which we can learn, allowing us to broaden our focus from events to context. We can see the complex interconnectedness of drivers of future change. We can pause our problem-solving and go into exploration mode. We can ask ourselves the uncomfortable and unpopular questions. Most of all, we can use the fact that the future is already present to start creating a better future in the present.

References

* This publication reflects the views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the views of the OECD or any of its members.

1 Philip Zimbardo and John Boyd, The Time Paradox: The New Psychology of Time That Will Change Your Life (New York: Atria Books, 2009).

2 Paul Saffo, ‘Six Rules for Effective Forecasting’, Harvard Business Review, July 1, 2007, https://hbr.org/2007/07/six-rules-for-effective-forecasting.

3 Rafael Ramirez and Angela Wilkinson, Strategic Reframing: The Oxford Scenario Planning Approach (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

4 Stephan De Spiegeleire, Matthijs Maas and Tim Sweijs, Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Defense: Strategic Implications For Small- and Medium-Sized Force Providers (The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, 2017).

5 Op. cit., Strategic Reframing.

6 Michael D. Ward, ‘Can We Predict Politics? Toward What End?’, Journal of Global Security Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, February 1 (2016): pp. 80–91, https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogv002.

7 Ibid.

8 Op.cit., Strategic Reframing; Riel Miller, Transforming the Future: Anticipation in the 21st Century (London: Routledge, 2018).

9 Attributed to Herman Kahn in J. Peter Scoblic, “Learning from the Future”, “Emerging from the Crisis”, Harvard Business Review, July-August 2020, https://hbr.org/2020/07/emerging-from-the-crisis#learning-from-the-futu….

10 Robert M. Grant, Augustus to Constantine: The Rise and Triumph of Christianity in the Roman World (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1990).

11 Hence the art and science of disciplined ‘superforecasting’: Philip Tetlock and Dan Gardner, Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction (London: Random House, 2015).

12 Ministerie van Defensie, ‘Eindrapport Verkenningen: Houvast Voor de Krijgsmacht van de Toekomst’, April 1, 2010.

13 Rem Korteweg et al., De Toekomst in alle Staten: HCSS Strategische Monitor 2013 (The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, 2013).

14 The moment a phenomenon is empirically observed, it stops being the future and becomes the present.

15 Betty S. Flowers, ‘The Art and Strategy of Scenario Writing’, Strategy & Leadership, vol. 31, no. 2 (January 1, 2003): pp. 29–33, https://doi.org/10.1108/10878570310698098.

16 National Intelligence Council, Global Trends: Paradox of Progress, 2017, https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/nic/GT-Full-Report.pdf.

17 Thomas Gauthier, ‘Décider dans l’incertitude : Et si vous vous mettiez à la rétroprospective ?’, The Conversation, April 20, 2020, http://theconversation.com/decider-dans-lincertitude-et-si-vous-vous-me….

18 John C. Camillus, ‘Strategy as a Wicked Problem’, Harvard Business Review, vol. 86, no. 5 (May 1, 2008), https://hbr.org/2008/05/strategy-as-a-wicked-problem.

19 OECD, “Debate the Issues: Complexity and Policy Making”, OECD Insights (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2017), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264271531-en.

20 Sohail Inayatullah and Peter Black, ‘Neither A Black Swan Nor A Zombie Apocalypse: The Futures Of A World With The Covid-19 Coronavirus’, Journal of Futures Studies, March 18, 2020, https://jfsdigital.org/2020/03/18/neither-a-black-swan-nor-a-zombie-apo….

21 Sarah Boseley, ‘WHO Declares Coronavirus Pandemic’, The Guardian, March 11, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/11/who-declares-coronavirus-….

22 IPCC, “Summary for Policymakers”, in Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty (Geneva: World Meteorological Organisation), p. 32, https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/spm/.

23 Op.cit., Strategic Reframing.

24 Op.cit.,Transforming the Future.

25 Also referred to as ‘poverty of the imagination’: in Transforming the Future, op.cit. .

26 Eric V. Larson, “Force Planning Scenarios, 1945–2016: Their Origins and Use in Defense Strategic Planning”, Product Page, 2019, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2173z1.html.

J. Peter Scoblic, “Learning from the Future”, Harvard Business Review, July/August 2020, https://hbr.org/2020/07/emerging-from-the-crisis.