Over the last few years, news about Russia’s conduct in the Western Balkans has resembled dispatches coming from the trenches of political and economic warfare: Moscow has slashed gas supplies, banned imports of agro-food products, conducted coordinated disinformation campaigns, nurtured nationalist organisations, deployed Cossack paramilitary groups, tested cyber defences and allegedly even tried to overthrow legitimate governments. This flurry of disruptive operations caught Europe by surprise and generated debate: does this resurgence herald Russia’s return to the region and if so, what is driving the comeback? What does Moscow want to achieve? What is the Russian modus operandi in the region? Is it confined only to coercion, as the headlines suggest, or is there a softer side to Russia’s power? Finally, looking retrospectively, did Russia’s approach bear fruit?

This Brief addresses this set of questions in greater detail, with two key findings. First, Russia’s policy in the region is executed by a network of Russian state and non-state actors who are blurring the traditional lines between the public and private domains. This allows the Kremlin to tap into the resources of informal institutions and hide behind a fog of deniability. Second, Russia has raised the cost of Western Balkan integration in the EU and NATO by exploiting the region’s political and economic vulnerabilities. That said, although Moscow was able to slow down the process, it has hitherto failed to alter the region’s steady drift towards Western institutions, at least for now.

The different faces of power

The myriad of destabilising actions in the Western Balkans has created an impression that Russia has successfully elbowed its way ‘back’ into the region. Yet the perception that post-Soviet Russia ever left the region is misleading: since the early 1990s, Russia has maintained a constant presence in the Western Balkans. Its objectives and the way it has cultivated and projected power have constantly mutated, however, primarily due to the interplay of four factors: constraints and opportunities stemming from war and peace dynamics in the Western Balkans, relations with Europe and the US, Russia’s self-perception and its power resource base.

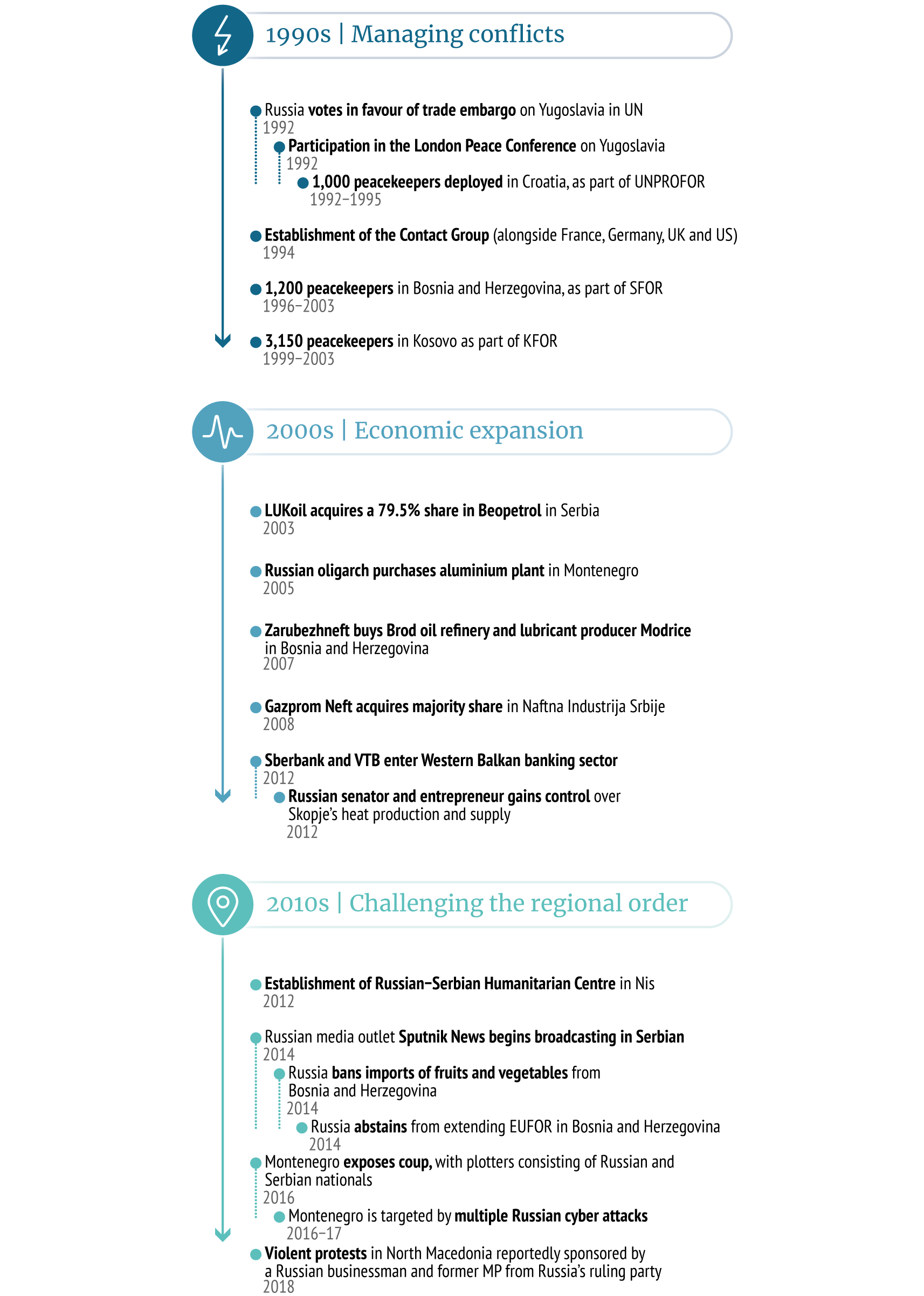

Ravaged by wars in the 1990s, the Western Balkans provided few legal business opportunities for outsiders. Just like other major powers, Russia’s policy in the region therefore focused mainly on conflict management. Even if the Kremlin timidly attempted to build an economic presence and leverage the gas supply contracts inherited from Soviet times, it largely relied on diplomatic means and its residual military power: Moscow put pressure on the warring parties, supported international sanctions, joined conflict resolution formats and proposed (as well as obstructed) diplomatic solutions. At the same time, Russia deployed peacekeepers and tolerated (if not encouraged) the constant stream of Russian fighters leaving for the Balkans. Overall, Russia’s power projection in the region sought to convert the political capital won through conflict management into influence and the status of a power broker. It did not work as smoothly as desired: regional clients often did not heed Russia’s advice, while NATO kept exercising the ‘responsibility to protect’. The alliance’s interventions in Kosovo, without a UN mandate, were interpreted in Moscow as unmistakable signs of the rise of a Western-driven unipolarity. With their hopes for co-management of European security dashed, uncritical Russian views of the EU and US as a constellation of friendly and like-minded powers had evaporated by the late 1990s.

Yet in the 2000s, Russia witnessed a sweeping change in the Kremlin and underwent a rapid economic recovery. This, in turn, reshaped both Russia’s self-perception and the way it views the world. Newly-elected President Vladimir Putin described himself as “a manager hired by Russia Inc.” and framed contemporary international relations in terms of fierce competition with developed economies for markets, investments and economic influence. Shortly after, Russian elites started to imagine Russia as a ‘liberal empire’ that could expand by attracting neighbours primarily via economic power and performance. As a result, Russian foreign policy acquired greater economic undertones at the same time as peace settled in the Western Balkans, allowing Russia to project its newly rediscovered mercantilism to grasp fresh economic opportunities in the region.

Projection of Russian power in the Western Balkans

Timeline

In the realm of hard security in the Western Balkans, Russia tacitly consented to unipolarity: Moscow relinquished the responsibility to police the region to NATO and the EU and the last Russian peacekeepers left Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2003. But as Russia completed its military drawdown, its energy giants, acting in concert with a number of shady entrepreneurs, flocked to the region. The infiltration of Russian capital was facilitated by a partial disinterest on part of the other powers to invest in an area with dilapidated socialist-era infrastructure, poor governance, a dependence on the supply of gas from Russia’s Gazprom (in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina) and unsolved conflicts and the 2008 global financial crisis. While Russia did not become the Western Balkan’s main trading partner or investor (with the exception of Montenegro), Russian businesses nevertheless made significant acquisitions in strategic sectors such as energy, heavy industry, mining and banking. For example, Zarubezneft controls both of the oil refineries in Bosnia and Herzegovina, granting it a quasi-monopoly in the market of oil-based products. Despite this impressive market penetration, some of Russia’s major investments proved to be money-losing exercises. Zarubezneft has reported significant financial losses in Bosnia and Herzegovina, for instance, but at the same time has signalled no intention to leave. What this and other similar cases reveal is that profit-making was often of secondary importance: the mercantilist drive sought to create dependencies and endow the Russian state with political influence in the region. In other words, mercantilism was disguising Moscow’s geopolitical objectives.

What drives the shift?

Russia’s assertive approach in the Western Balkans in the 2010s is often associated with the political and diplomatic standoff with Europe triggered by the illegal annexation of Crimea and cancellation of the Russian-sponsored South Stream gas pipeline. However, these matters accelerated rather than initiated the shift of Russia’s policy in the region.

In the 2010s, the Kremlin continued to encourage Russian businesses to invest in strategic sectors. Slowly, however, economic expansion gave way to an openly geopolitical and assertive posture and greater activity in the security field. Around this time, the Russian Ministry of Exceptional Situations (which also has paramilitary units), secured a presence in the Serbian-Russian Humanitarian Centre in Nis through an agreement with the Serbian government. Later, Russia requested that their staff be granted diplomatic status, a move which raised suspicions that the Centre might be performing undisclosed functions (in the field of security and intelligence gathering) in addition to its declared civilian goals.

Furthermore, 50 years after the Soviet Union lost its only naval base in the region (the Pasha Liman base in Albania), the Adriatic Sea has re-appeared on Russia’s radars. In 2013, Russia reportedly approached the Montenegrin government with a request for regular access to the seaports of Bar and Kotor for its battleships. More or less at the same time, Moscow fuelled the proliferation of disruptive nationalist organisations in Bosnia and Herzegovina, expanding the shadow infrastructure which can be relied upon in case of need. This trend also intensified substantially from 2014 onwards.

Europe’s responses to Russian attempts to undermine Ukrainian statehood only partially explain the Kremlin’s actions in the Western Balkans. On the one hand, the mutation is co-determined by domestic political processes in Russia. Unlike in the 2000s when the president saw himself akin to an appointed CEO accountable to his shareholders, Putin increasingly perceives himself as a national leader who is above society and the political elites. In this latter capacity, the president increasingly tends to derive legitimacy from foreign policy accomplishments rather than from economic performance at home. The shift is also a reflection of Russia’s dwindling economic resources and recovered coercive kinetic prowess – the result of the wide-ranging military reforms carried out in the aftermath of the 2008 war in Georgia. The changing balance in the distribution of resources that underpin Russia’s power has therefore manifested itself in a more militarised and subversive foreign policy.

On the other hand, the shift is conditioned by Russia’s perceptions of current developments in the region. As one Russian observer put it, “the EU-centric approach in the region has failed, the states in the region are neither doing better nor are more prosperous than before.” This is not an isolated opinion, but a mainstream view: Russia’s foreign minister described the EU’s position as “powerless” when commenting on the most recent spat between Serbia and Kosovo. These perceptions might be wildly at odds with reality, but they nevertheless shape Russia’s expectations and inform its decision-making. Moscow does not anticipate the situation to improve, as it sees the EU as an entity increasingly contested from the inside. Furthermore, Russian experts believe that EU influence is being weakened by the rise of extra-regional powers, including China, Turkey and the Gulf states. This reading of regional dynamics makes Russia question the feasibility of European integration as a meta solution to regional problems and organising idea around which order in the Balkans should exist. In the Russian view, the region is ripe for change and Moscow stands ready to provide a ‘helping hand’ in order to bring this about.

Make the Balkans multipolar again

A careful reading of these overlapping drivers can help distil Russia’s policy objectives in the Western Balkans. First, Russia’s regional policy performs a diversionary function: time and money are finite resources, which is why the Kremlin seeks to divert Europe’s attention and funds away from the eastern neighbourhood and force it to prioritise stability in the Western Balkans. In this regard, Russian experts interpret the launch of the Berlin Process in 2014 (which seeks to foster regional integration) as a direct reaction to Moscow’s more assertive posture in the region.

But Russia’s policy is not only designed to trigger a reaction from Europe, but also to blunt its effectiveness. With this in mind, Moscow is deliberately slowing down progress on the settlement of regional conflicts/disputes and trying to hinder NATO and EU enlargement efforts. Often, Moscow does not have to create entirely new problems: it is quite enough to exacerbate existing ones. Russia’s subversive efforts (such as fuelling protests) and diplomatic attempts (such as questioning the legitimacy of agreements) to derail the resolution of the ‘name issue’ between Greece and North Macedonia or its support for the highly divisive referendum in Republic Srpska on the entity’s national day are telling in this sense.

Second, Russia’s destabilising tactics in the Balkans can be considered a tit-for-tat move for perceived tactics practised by the EU in the eastern neighbourhood. As one Russian expert put it: “Moscow also believes that the West has been stirring up trouble in Russia’s neighbourhood in recent years"; it thus feels entitled to “payback.”

The grand aspirational objective is to bring back what is deemed in Moscow to be a more natural state of play for the Balkans: multipolarity.

Third, Russia’s policy in the region is also about recruiting all sorts of auxiliary support for the Kremlin’s international agenda. Russia relies on local allies to roll out the red carpet at a time when few in Europe would grant the Russian leadership such treatment. Moscow also counts on local clients for friendly votes in the United Nations on issues related to conflicts in the Eastern Partnership (EaP) states and expects them not to align with the EU’s sanctions on Russia. Furthermore, the Western Balkans provides fertile terrain for Russia and its proxies to recruit fighters for Moscow’s (un)declared wars. For instance, the Russian illegal, private military company Wagner Group, which reportedly has close links to Russia’s military intelligence service and was active in Donbas and Syria, has counted Serbian fighters (among others) in its ranks. At the same time, it is an important region for Russia’s religious diplomacy, which is often aligned with the agenda of the Russian state. The Moscow Patriarchate, for example, seeks the support of local churches in its contest for pre-eminence in the Orthodox world with the Patriarchate of Constantinople.

Last but not least, the grand aspirational objective of Russia’s current policy is to deconstruct step by step what it sees as an unjust unipolar regional order underpinned by Western institutions and to bring back what is deemed in Moscow to be a more natural state of play for the Balkans: multipolarity. The Kremlin resorts to destabilisation and employs the economic leverage gained in 2000s to obtain a seat at the table and strengthen its voice in regional affairs. There are hopes that greater regional coordination with Turkey and China will help to precipitate the ascent of multipolarity, too. According to Russian experts, a ‘concert of powers’ – where Russia is one of multiple managers of the Western Balkans – is the only way to escape the current regional rivalry and move towards a better handled multi-stakeholder order. Russia’s overt and covert actions aimed at upsetting local power balances (e.g., the militarisation of the police in Republic Srpska or abstaining during a UN vote on the extension of the mandate of the EU’s mission in Bosnia and Herzegovina, EUFOR Althea, in 2014) may be interpreted as early moves to challenge the current political status quo.

Change and continuity in Russia’s modus operandi

It is not the first time that the Russian Federation or its predecessors have employed disruptive tactics in the region: the Soviet Union tried to limit the autonomy of regional leaders, weaken their domestic standing and then even attempted to oust them from power in Yugoslavia (1947-1958) and Albania (1960-69) using political and economic warfare. Yet although Russia’s current approach is reminiscent of some kind of déjà vu, there are certain features which distinguish the present from the past.

Today, Russia relies on a much wider array of actors for support than before: intelligence officers, political operatives, oligarchs, ultranationalist organisations, state companies, hackers, Cossacks, illegal private military companies, state-owned media outlets, criminals and internet trolls now all aid Moscow in its objectives. Despite this hybrid amalgam of actors, what is clear is that their actions in the region, besides advancing narrow private goals (e.g., money-making or gaining clemency for an individual’s wrongdoings inside Russia), broadly overlap with the agenda of the Russian state.

One way for Russia to deny responsibility for the actions of these actors is to claim they have no connection with – and/or do not represent – the Russian state. And if the Weberian definition of the state is applied (one centred on a single legal authority, which exercises its power via legal formal rational institution), in some cases, Russia may be entitled to the benefit of the doubt. However, if Russia is approached as being a ‘network state’, in which the duality of weak formal and powerful informal institutions coexist and where the borders between what is public and what is private are blurred, then Moscow’s deniability becomes highly implausible. This is particularly so given that Russia’s operations in the Western Balkans are often the result of public-private partnerships, mediated and coordinated by informal power networks.

Unlike in the 1950s and 1960s, the countries of the Western Balkans today have much more open political and economic systems. This provides Russia with more opportunities: not only to infiltrate state structures, but also to paradoxically conduct subversive actions alongside charm offensives. Unlike the Soviet Union, Russia therefore has the chance to simultaneously build alliances with corrupt politicians whose legitimacy is rooted in identity politics, acquire assets and convert this economic presence into political clout, become involved in high-visibility and prestige-generating projects (e.g. Gazprom is the official sponsor of Serbian Red Star football club) and shape people's opinions via Russian-sponsored mass media outlets.

Although the Soviet Union officially practiced state atheism, it leveraged the compliant local Orthodox Church for domestic and foreign policy purposes. Still, in the case of its normative duel with its unruly ‘clients’ in the Western Balkans, Moscow relied on Communist ideology and pan-Slavism rather than religion to assert its primacy. In the 1990s, however, Russia’s policy in the region regained a religious dimension, returning to the Tsarist tradition of utilising the Church in its policy in the Western Balkans. Subsequently, Russian reliance on religious diplomacy greatly expanded in the 2010s. Russia is well placed to exploit these real and perceived religious bonds: there are sizable Orthodox communities in the Western Balkans (Serbia 88%, Montenegro 72%, North Macedonia 65%, Bosnia and Herzegovina 31%) and religion plays a crucial role in people’s private lives and their definitions of national identity (88% of respondents in North Macedonia, 72% in Serbia and 71% in Montenegro declared themselves to be religious).

In the 1990s, Russia’s policy in the region regained a religious dimension, returning to the Tsarist tradition of utilising the Church in its policy in the Western Balkans.

Russia exploits this religious factor to disrupt, attract and empower. Russian media often frames regional rivalries in religious terms, something designed to exacerbate already existing tensions: for instance, Russia’s portrays the animosity between Serbs and Albanians primarily as a clash between Orthodox Christians and Muslims. Russia uses religion to boost its soft power, too. In the 2010s, Russian oligarchs and state companies heavily invested in high-visibility construction projects which erected churches and other religious sites in North Macedonia, Kosovo, Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Finally, Russia appeals to religion to empower local clients practicing divisive identity politics in the region: in 2014, for example, Patriarch Kirill awarded prominent Republika Srpska politician Milorad Dodik with the ‘Prize of Unity of Orthodox Nations’.

One distinctive feature of Russia’s contemporary modus operandi is its savvy use of strategic communication in order to maximise the effect of both its diplomatic and subversive actions. To this end, Russia strives to paint a picture of a power that has returned to the region to protect its Slavic brothers. For example, Russia’s transfer of six MiG-29’s to Serbia was presented by Sputnik as a move that would ‘save’ Serbia’s air force, whereas in reality these jets are outdated and Serbia will have to fund the upgrades by itself. While Moscow seeks to cultivate its positive image in the region, a heavily negative spin is put on the presence of the EU, NATO and their member states: NATO is often accused of anti-Serbian bias, the EU is blamed for destabilisation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Albania and Bulgaria are accused of harbouring desires to partition North Macedonia. Another distinctive feature of Russia’s strategic communication is a proclivity to exaggerate Russia’s disruptive potential in the region. The case of a group of Russian Cossacks, who arrived in Republic Srpska ahead of a crucial presidential vote in 2014, speaks volumes. An email exchange retrieved by CyberJunta (a Ukrainian hacker group) first reveals that consultants working for Russian businessman Konstantin Malofeev (who has been active in the region) organised a controlled leak of a photo from his ‘secret’ meeting with Milorad Dodik. This leak was followed by a short comment in the press, hinting that Malofeev’s presence was linked to the arrival of Russian Spetsnaz (special operations units) disguised as Cossacks. What all this was meant to imply was that a Crimea-like scenario was a distinct possibility were Dodik not to be re-elected. The case reveals the Russian network state’s growing propensity to exploit the media, sometimes by simply bluffing.

Is Russia winning or losing?

Russia’s return to undisguised geopolitics and the sophisticated arsenal of tools it employs in the region begs the question: is Moscow winning or losing? Moscow has definitely managed to catch Europe’s attention and its capacity to unravel the existing regional peace is taken more seriously than before. As a result, the EU and its member states have had to dedicate more time and resources to the Western Balkans. Yet somewhat ironically, this means that Russia may in fact face more push back on many fronts in the region than it did before: the BBC closed its Serbian service in 2011, for example, but brought it back on air in 2018. The EU is set to allocate more resources for strategic communications in the Western Balkans, and Russia’s attempts to derail the resolution of the ‘name issue’ forced Greece to expel a number of Russian diplomats. In this sense, Russia’s victory in catching Europe’s eye might prove a pyrrhic one.

At first glance, Russia has successfully hindered almost every step the Western Balkan states have taken to move closer to NATO or the EU. This helped President Putin to consolidate his popularity and strongman image in Serbia (with a 57% approval rating there, he is the most trusted foreign leader), while sustaining sympathy in Republic Srpska, the northern municipalities in Kosovo, a pro-Russian base in Montenegro and the nationalist political party VMRO-DPMNE in North Macedonia. Yet Russia’s diversionary tactics have not won it new friends in the region. On the contrary, Russia’s bench of locals allies is getting smaller and the range of support it can rely on is ever narrower. For instance, if in 2008 Albania was the only country in the Western Balkans which voted for the UN resolution on the return of internally displaced people (IDPs) from Abkhazia and Ossetia (which Russia regularly tries to obstruct), ten years later three states from the Western Balkans voted for it (Albania, Montenegro and North Macedonia), and while Serbia previously voted against, it now abstained together with Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Even for Serbia, some of Russia’s actions on its territory go too far. In the summer of 2018, the Serbian police closed down a ‘patriotic youth camp’ organised by the Russian nationalist group E.N.O.T Corp, whose members had fought in Donbas. Belgrade has also not caved to Russia’s demands to offer diplomatic immunity to the Russian officers at the Serbian-Russian Humanitarian Centre in Nis. It seems that Belgrade is happy to be Russia’s privileged partner and extract dividends accordingly, but has no desire to become its military bridgehead in the region.

Russia’s victory in catching Europe’s eye might prove a pyrrhic one.

Furthermore, despite the obstacles put in place by Russia, Montenegro has joined NATO and North Macedonia is in the final stages of becoming a member, too, while Bosnia and Herzegovina received a Membership Action Plan (Russia’s ally Milorad Dodik has, however, so far managed to block its activation). In addition to the progress made in EU accession talks with both Serbia and Montenegro, North Macedonia is also much closer to opening accession negotiations than a few years ago. That said, Russia still has a few cards up its sleeve that it can play in Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina to slow down these processes and keep Belgrade and Pristina and Sarajevo and Banja Luka trapped in their current lose-lose situations.

In the field of energy, Russia has been stonewalling progress in terms of the diversification of energy markets in the Western Balkans. Yet, even in this field where Russia holds powerful sway, Gazprom has suffered setbacks. Serbia has had to align its gas import contract with Gazprom with EU directives, while the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) has approved funds for a Croatia-Bosnia and Herzegovina gas interconnector, thereby creating the conditions for the diversification of the latter’s supply and challenging Gazprom’s monopoly in the near future.

All in all, the Russian network state has racked up several tactical successes which have not changed the strategic direction of the Western Balkans so far. But Russia cannot be credited exclusively for these small wins: without fertile political ground (in the form of weak governance, corruption, unsettled disputes) and Western Balkan rulers who use Russia in their localised power games, Moscow would not have been able to significantly worsen polarisation or spark further tensions. Therefore, in the coming years the EU strategy towards the region will require not only pushback against Russia’s hostile actions, but bolder efforts towards encouraging and sustaining deep reforms. Unlike Russia, the EU has an attractive model to offer and the financial power to succeed; but the sustained political resolve to operationalise these advantages is still a necessity.

References

* The author is thankful to Dimitar Bechev for his insightful comments on early drafts and to Marius Troost for invaluable research assistance in the course of writing this Brief.

1. See, Rodolfo Toè, “Russian Ban Alarms Bosnia Fruit Producers”, Balkan Insight, August 5, 2016, http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/bosnian-fruit-producers-scared-…; “Russia Reduces Gas Flow to Serbia over Unpaid Debt”, Novinite, November 1, 2014, https://www.novinite.com/articles/164467/Russia+Reduces+Gas+Flow+to+Ser…; Saska Cvetkovska, “Russian Businessman Behind Unrest in Macedonia”, OCCRP, July 16, 2018, https://www.occrp.org/en/investigations/8329-russian-businessman-behind…; “Second GRU Officer Indicted in Montenegro Coup Unmasked”, Bellingcat, November 22, 2018, https://www.bellingcat.com/news/uk-and-europe/2018/11/22/second-gru-off…; Maja Zivanovic, “Russia’s Fancy Bear Hacks its Way Into Montenegro”, Balkan Insight, March 5, 2018, https://balkaninsight.com/2018/03/05/russia-s-fancy-bear-hacks-its-way-….

2. Dimitar Bechev, Rival Power (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), p. 2-3; James Headley, Russia and the Balkans (London: Hurst, 2008).

3. Headley, Russia and the Balkans, p. 203.

4. The majority of whom have seen before action in Afghanistan, Transnistria, Abkhazia and Nagorno-Karabakh. Mikhail Polikarpov, Balkanskiy Rubezh. Russkiye dobrovoltsi v boyakh za Serbiyu [The Balkan frontier. Russian volunteers in battles for Serbia] (Pyati Rim: Moscow, 2018).

5. Sergey Romanenko and Artyem Ulunyan, “Balkanskaya politika 90-kh godov: v poiskakh smisla” [Balkan politics of the 90s: in search of meaning], Pro et Contra, vol. 6, no. 4 (2001), p. 51.

6. This designation is without prejudice to positions on status, and is in line with UNSCR 1244/1999 and the ICJ Opinion on the Kosovo declaration of independence.

7. Headley, Russia and the Balkans, p. 420.

8. President of Russia, Ezhegodnaya bol’shaya press-konferentsiya [Annual big press-conference], Moscow, February 14, 2008, http://kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/24835.

9. Vladimir Putin “Annual Address to the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation”, April 18, 2002, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/transcripts/21567.

10. Anatoliy Chubais, “Missiya Rossii v XXI vekye” [Russia’s mission in the 21st century], Nezavisimaya Gazeta, October 1, 2003, http://www.ng.ru/ideas/2003-10-01/1_mission.html.

11. Bechev, Rival Power, pp.51-85.

12. “Assessing Russia’s Economic Footprint in the Western Balkans”, Center for the Study of Democracy, 2018, http://www.csd.bg/artShow.php?id=18131.

13. “Assessing Russia’s Economic Footprint in Bosnia and Herzegovina”, Center for the Study of Democracy, 2018, https://csd.bg/fileadmin/user_upload/publications_library/files/2018_01….

14. Maja Garaca Djurdjevic, “Russia’s Political Interests Drive Investments in Bosnia”, Balkan Insight, July 4, 2016, https://balkaninsight.com/2016/07/04/russia-s-political-interests-drive….

15. Reuf Bajrović, Vesko Garčević & Richard Kraemer, “Hanging by a Thread: Russia’s Strategy of Destabilization in Montenegro”, FPRI Russian Foreign Policy Paper, June 2018, Philadelphia, https://www.fpri.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/kraemer-rfp5.pdf, p. 7.

16. Cristina Maza, “Another Ukraine? Russia backs separatist politician’s military buildup in Bosnia and Hercegovina, research shows”, Newsweek, March 16, 2018, https://www.newsweek.com/another-war-bosnia-russia-backs-separatist-pol….

17. Russian expert remarks during closed-door debate Berlin, 2017.

18. Entina et al., “Where Are The Balkans Heading?”, Valdai Club, September 2018, http://valdaiclub.com/files/19381/.

19. “Lavrov on situation in Balkans”, RBK, May 29, 2019, https://www.rbc.ru/rbcfreenews/5cee5f1e9a79473304e6dc82.

20. Entina et al., “Where Are The Balkans Heading?”.

21. Ibid

22. Bojana Zoric, “Assessing Russian impact on the Western Balkan countries’ EU accession: cases of Croatia and Serbia”, Journal of Liberty and International Affairs, vol. 3, no. 2 (2017), pp. 9-18.

23. “Greece ‘orders expulsion of two Russian diplomats’”, BBC News, July 11, 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-44792714.

24. Danijel Kovacevic et al., “Russia Lends Full Backing to Bosnian Serb Referendum”, Balkan Insight, September 20, 2016, https://balkaninsight.com/2016/09/20/disputed-bosnian-serb-referendum-d….

25. Maxim Samorukov, “Russia’s Tactics in the Western Balkans”, Carnegie Europe, November 3, 2017, http://carnegieeurope.eu/strategiceurope/74612.

26. Maja Zivanovic, Serbia Stands by Russia at UN on Crimea Resolution, Balkan Insight, December 20, 2017, https://balkaninsight.com/2017/12/20/serbia-back-russia-on-crimea-at-un….

27. Aubrey Belford et al., “Leaked Documents Show Russian, Serbian Attempts to Meddle in Macedonia”, OCCRP, June 4, 2017, https://www.occrp.org/en/spooksandspin/leaked-documents-show-russian-se….

28. Maja Zivanovic, “Donbass Brothers: How Serbian Fighters Were Deployed in Ukraine”, Balkan Insight, December 13, 2018, http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/donbass-brothers-how-serbian-fi….

29. Vuk Vuksanovic “Serbs Are Not ‘Little Russians’”, The American Interest, July 26, 2018, https://www.the-american-interest.com/2018/07/26/serbs-are-not-little-r….

30. Entina et al., “Where Are The Balkans Heading?”.

31. Dennis P. Hupchick, The Balkans (New York: Palgrave, 2002), pp.403-411; Robert Owen Freedman, Economic Warfare in the Communist Bloc (New York: Praeger, 1970), pp.18-102.

32. Jasna Vukicevic, Robert Coalson, “Russia’s Friends Form New ‘Cossack Army’ In Balkans”, RFE/RL, October 18, 2016, https://www.rferl.org/a/balkans-russias-friends-form-new-cossack-army/2….

33. Mark Galeotti, The Vory (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), p. 252.

34. Vadim Kononenko & Arkady Moshes (eds.), Russia as a Network State (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).

35. “German prosecution investigates RS president for corruption”, B92, November 15, 2012, https://www.b92.net/eng/news/region.php?yyyy=2012&mm=11&dd=15&nav_id=83…; “Former Macedonian Leader Faces Two Years in Prison After Losing Appeal”, RFERL, November 10, 2018, https://www.rferl.org/a/former-macedonian-prime-minister-gruevski-faces….

36. Hupchick, The Balkans, pp. 252-256; Lenard J. Cohen, “Russia and the Balkans: Pan-Slavism, Partnership and Power”, International Journal, vol. 49, no. 4 (1994).

37. “Mapped: The world’s most (and least) religious countries”, The Telegraph, January 14, 2018, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/maps-and-graphics/most-religious-cou….

38. Ebi Spahiu, “Russia Expands Its Subversive Involvement in Western Balkans”, Jamestown Foundation, January 23, 2017, https://jamestown.org/program/russia-expands-subversive-involvement-wes…; Jasmina Scekic, “Russia’s Orthodox Culture Warrior Comes to the Aid of Kosovo’s Serbs”, RFERL, February 2, 2014, https://www.rferl.org/a/kosovo-serbs-russian-orthodox-warrior/25250663….

39. “Russia finances repair of Serb shrines in Kosovo”, B92, July 22, 2010, https://www.b92.net/eng/comments.php?nav_id=68608.

40. “President of Republic of Srpska received high award in Moscow”, Serbian Orthodox Church, March 12, 2014, http://www.spc.rs/eng/patriarch_kirill_leads_14th_ceremony_awarding_pri….

41. Yevgeniy Yemelyanov, “Vozvrasheniye v Yugo-Vostochnuyu Yevropu: ‘balkanskaya’ nyedelya prezidenta Putina” [Return to south-eastern Europe: president Putin’s ‘Balkan’ week], Life.ru, October 3, 2018, https://life.ru/t/%D0%BF%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%B8%D1%82%D0%B8%D0%BA%D0%B0/1157….

42. “MiG-29 Fighter Jets From Russia to ‘Save’ Serbia’s Air Force”, Sputnik, December 23, 2016, https://sputniknews.com/military/201612231048907647-russia-serbia-mig29….

43. “Developments in Macedonia directed from outside — Lavrov”, TASS, May 20, 2015.http://tass.com/world/795744; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Kommentariy ofitsiyal’nogo prestavitelya MID Rossii M.V. Zacharovoy otnocitel’no reaktsii ES na sobitiya v Respublikye Serbskoy [Comments by official spokesperson of the MFA of Russia M.V. Zacharova concerning EU’s response to events in Republika Srpska], Moscow, December 28, 2018, http://www.mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/news/-/asset_publisher/cKNonkJE02Bw…; https://sputniknews.com/europe/201903231073480178-nato-1999-bombing/.

44. Christo Grozev, “The Kremlin’s Balkan Gambit: Part I”, Bellingcat, March 4, 2017, https://www.bellingcat.com/news/uk-and-europe/2017/03/04/kremlins-balka….

45. “Merkel Concerned about Russian Influence in the Balkans”, Spiegel, November 17, 2014, https://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/germany-worried-about-russi….

46. Arun Kakar, “BBC launches Serbian digital news and social media in last of World Service expansion’s 12 new language outlets”, Press Gazette, March 28, 2018, https://www.pressgazette.co.uk/bbc-launches-serbian-digital-news-and-so….

47. “Opinion Poll: Serbs trust Putin – Rise of Euroscepticism”, IBNA, January 3, 2019, https://balkaneu.com/opinion-poll-serbs-trust-putin-rise-of-eurosceptic….

48. United Nations, “Status of internally displaced persons and refugees from Abkhazia, Georgia”, A/RES/62/249, New York, May 15, 2008; United Nations, “Status of internally displaced persons and refugees from Abkhazia, Georgia and the Tskhinvali region/South Ossetia, Georgia”, A/RES/72/280, New York, June 18, 2018, Voting data available at unbisnet.un.org.

49. “Serbian Police Close Paramilitary Youth Camp Run by Ultranationalists, Russian Group”, RFERL, August 17, 2018, https://www.rferl.org/a/serbian-police-close-paramilitary-youth-camp-ru….

50. “Serbia: Gazprom to increase gas deliveries to Serbia by 15 % in 2018”, Serbia Energy, January 10, 2018, https://serbia-energy.eu/serbia-gazprom-increase-gas-deliveries-serbia-….

51. “EBRD to Fund Gas Interconnection between Bosnia and Croatia”, Total Croatia News, October 20, 2018, https://www.total-croatia-news.com/business/31816-ebrd-to-fund-gas-inte…