In the wake of their third Joint Declaration, signed in January 2023, the European Union (EU) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) confirmed that they have ‘reached tangible results in countering hybrid threats’ while aiming to take their ‘partnership to the next level on the basis of long-standing cooperation’ (1). The ongoing war in Ukraine illustrates the fact that hybrid threats have become an integral part of contemporary warfare, which increasingly combines conventional and unconventional tools of interference with lethal effects. There is not one commonly agreed definition of hybrid threats and the main responsibility to address them lies with the targeted country. However, this does not stop the EU and NATO from combining their capabilities and expertise to develop, adapt and tailor their tools to help their Member States and partners address an evolving range of hybrid threats.

The European Centre of Excellence (CoE) for Countering Hybrid Threats, operating under the auspices of both EU and NATO members, defines the term ‘hybrid threat’ as ‘an action conducted by state or non-state actors whose goal is to undermine or harm a target by influencing its decision-making at the local, regional, state or institutional level’ (2). The CoE has identified 13 domains, including the political, military, economic and information realms, where hybrid actions take place, using a broad range of tactics which are designed to make it difficult to detect and attribute the attacks with absolute certainty. The purpose is to blur the lines between legal and illegal, internal and external factors by combining conventional and unconventional means of interference.

Hence, the effective countering of hybrid threats remains a common concern for both organisations which dedicate increasing and targeted resources to the issue across various regions (3), including in the Western Balkans (4). Due to the ambiguous nature of hybrid conflicts and the lower costs compared to conventional warfare, both the EU and NATO recognise the need to constantly adapt their policies and instruments and adopt a whole-of-society approach when deterring, detecting and countering hybrid attacks. Therefore, the EU’s and NATO’s ‘concerted approach on security and stability in the Western Balkans’ (5) has been a strategic objective for both actors throughout the last three decades.

Despite these efforts, numerous reports indicate that the Western Balkans are being particularly targeted by foreign interference and disinformation campaigns through hybrid attacks (6). This Brief first examines which prominent hybrid threats are destabilising the region, and the EU’s and NATO’s approaches. It then analyses how cooperation between the two organisations fosters stability in the region and suggests how Europe can further enhance its resilience and deterrence capacities.

Disruptive effects of hybrid threats in the Western Balkans

A region under attack

In the Western Balkans, several countries such as China, Türkiye and some Gulf countries are increasingly pursuing influence operations through building economic interdependencies or investing in media organisations or critical infrastructure. Yet, Russia remains the leading actor, and does not shy away from overt interference in a broad range of sectors. These efforts undermine the capacity of some Western Balkan countries to pursue closer European or transatlantic ties. By mounting hybrid operations in the region, the Kremlin also attempts to ‘steer Western focus away from [other] disturbing actions elsewhere’, such as Russia’s protracted conflict in Georgia or unprovoked war in Ukraine.

The energy dependence of the Western Balkan countries is one of their major vulnerabilities reflecting asymmetric power relationships, and one that the Kremlin is keen to exploit. Control of the energy supply has also provided Russia, which is now using south-eastern Europe instead of Ukraine as a transit route for its energy exports, especially gas, with significant economic and political leverage. However, Russia also invests in many other sectors in the region. For example, Russia’s extensive investments in the retail sector in Montenegro demonstrate the considerable presence of Russian capital in the country, leading to growing economic interdependence, a situation that Russia tends to exploit for purposes of economic coercion as part of a hybrid warfare strategy (7). On top of this, Russia does not hesitate to exacerbate domestic conflicts, and provide political and financial support, for example, to the Serbian entity Republika Srpska in Bosnia and Herzegovina (8).

Hence, the lines between influence operations and hybrid attacks remain fragile, exploitable and often blurred (9), and deserve the close attention of both the EU and NATO, as their reach is not limited by physical borders. Furthermore, the region struggles with internal quarrels and grievances such as the Serbia-Kosovo licence plate dispute (10), ongoing battles over ethnic, cultural or religious differences, and political instability within countries. This allows hybrid attacks to thrive on fertile soil and exacerbates existing domestic vulnerabilities, including governance deficits and societal divisions.

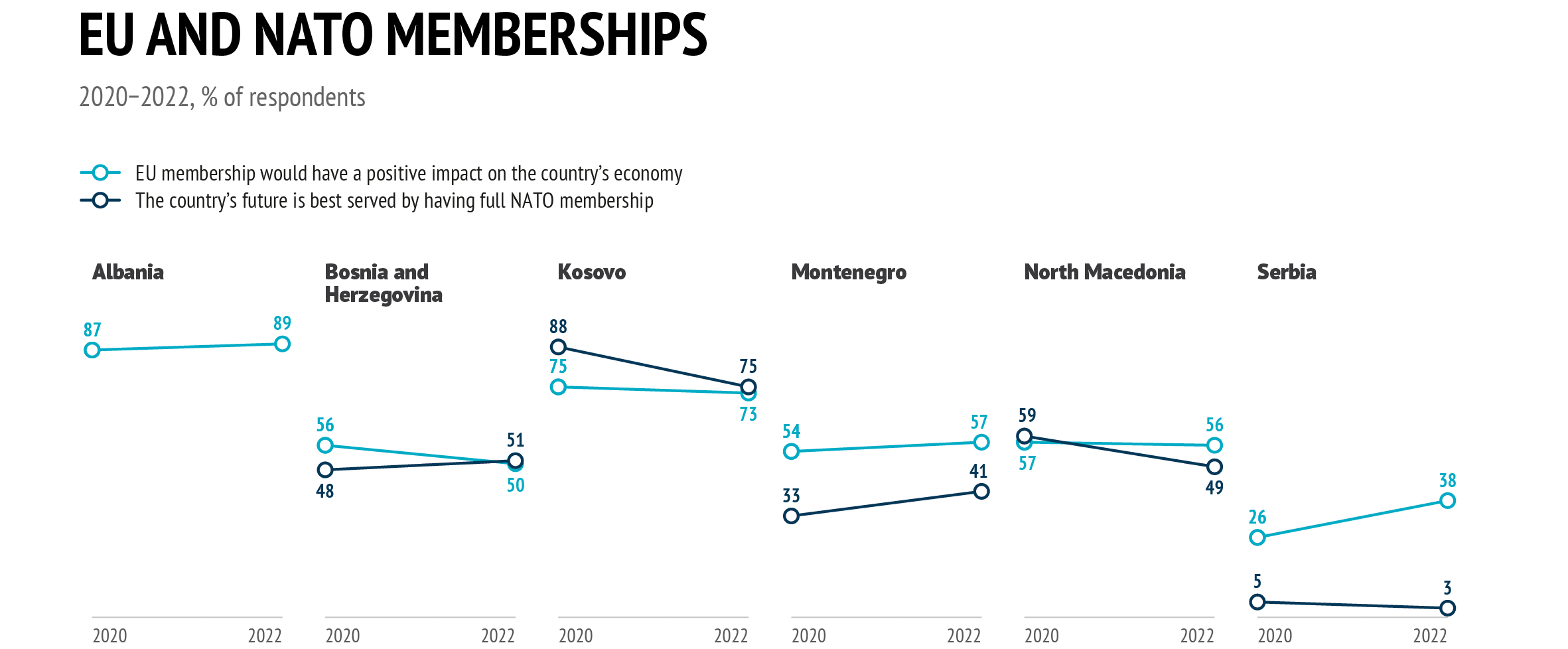

Moreover, in recent years, information manipulation and partnerships with local media have become increasingly prominent within hybrid campaigns led by the Kremlin in the region. Some key anti-Western narratives (or pro-Russian ones) have continued to play a disruptive role in the Western Balkans’ public spheres, as part of Russia’s efforts to undermine the credibility of the EU and NATO in the region. Two commonly used albeit contradictory narratives have been disseminated in the region over the years: ‘the EU is hegemonic’ and ‘the EU is weak’ (11). Other recent and recurring narratives propagated by Russian state-linked outlets claim that ‘having NATO in Kosovo is a risk for the population as the West is expert in creating conflict’ (12) or that ‘the West is using Kosovo to break Serbia’s ties with Russia and China’ (13). Those creating or amplifying such manipulated narratives know how to exploit their target audiences’ vulnerabilities and adapt their messages for maximum impact. This further erodes citizens’ trust in the so-called Western institutions and can be observed in the relatively low or fluctuating support for EU or NATO membership, or the reluctance to align with their foreign policies (14).

The Open Society Institute’s Media Literacy Index shows that one of the reasons why the Western Balkan countries are vulnerable to information manipulation is their comparably low capacity to detect and counter disinformation through political and media literacy, national education and media freedom. Out of 41 European countries ranked in the Media Literacy Index 2022 (15) the Western Balkan countries, particularly Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia, are identified as having the lowest potential to withstand the negative impact of manipulated information. In Serbia, for example, where Euronews has signed a deal to launch Euronews Serbia with Serbian media group HD-WIN, owned by telecoms operator Telekom Srbija (16), researchers have drawn attention to the risk that news may be presented with a pro-government spin, which may encourage anti-Western attitudes (17). Since disinformation in the Western Balkans has become commercialised and lucrative, economic interests also sustain these activities (18).

The need to foster a culture of independent journalism and media pluralism in the region continues to be an important focus for EU-NATO cooperation. Both organisations have adopted a more concerted approach since 2016 to assist in building resilience against foreign interference and manipulation. While bringing together both toolboxes remains a challenge, it is a necessary next step to reach a new level of partnership as devised in the third Joint Declaration. This is even more timely, when the European NATO pillar is expanding with the memberships of Finland and Sweden, and as both organisations’ interests increasingly overlap, including in countering hybrid threats.

The involvement of third actors like Russia and China in the region and its consequences, has also been a key factor in the EU and NATO moving forward with their enhanced cooperation in the Western Balkans. While China is increasingly assertive in the economic sphere and exploits structural and financial weaknesses by creating financial dependencies, Russia’s role transcends both the political and economic sphere. Playing on its cultural and religious ties within the region, Russia has chosen the tactic of a ‘unified form of nationalism underpinned by an imperialistic vision of uniting Slavic and Orthodox people’ (19). This approach presents the greatest peril for the Euro-Atlantic integration of the region, providing potential for Russia to exert power and influence, mostly over Serbia, Montenegro, Republika Srpska in Bosnia and Herzegovina, or Northern Kosovo — home of the Kosovar Serbs (20).

The EU’s and NATO’s approach

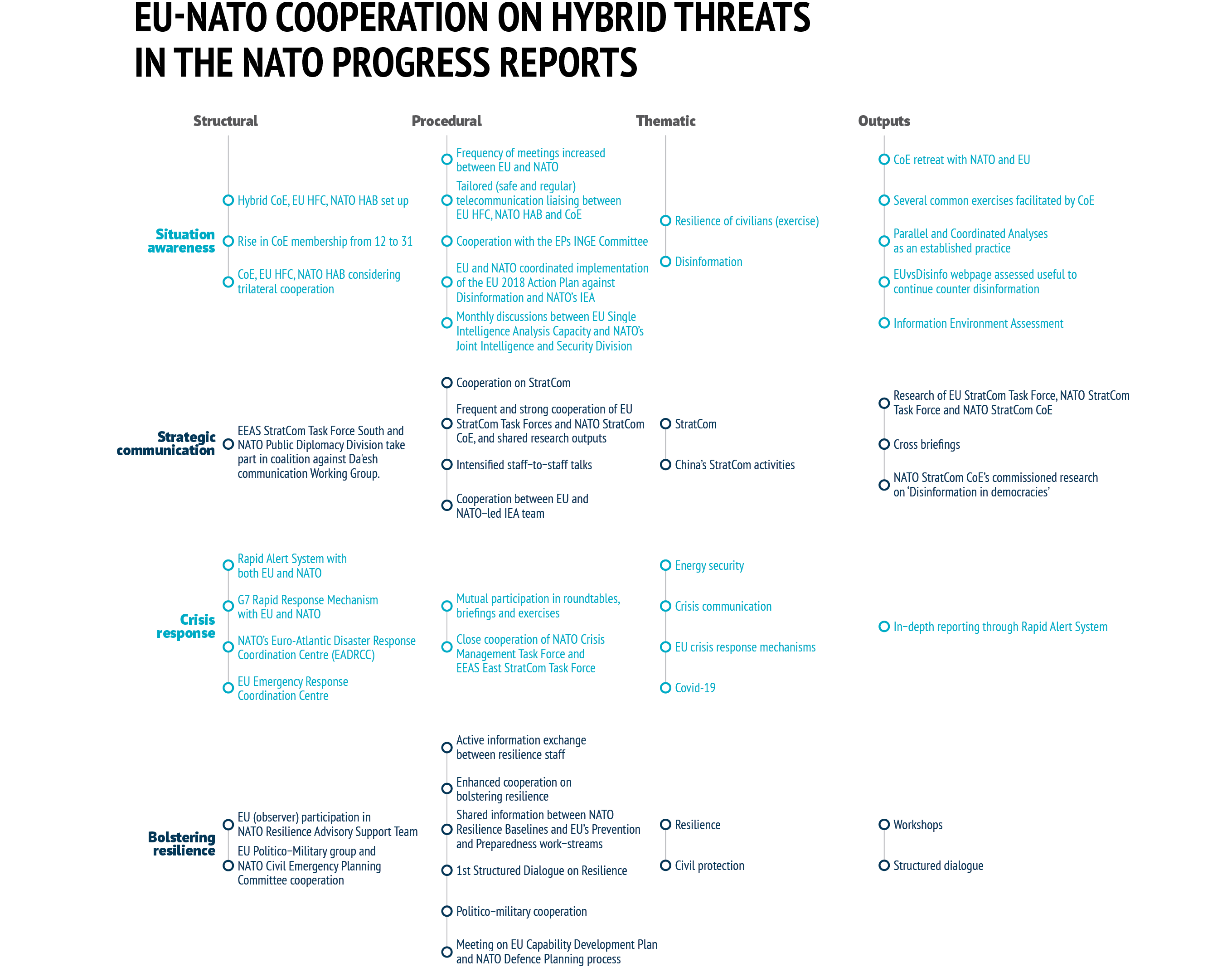

Since 2016, NATO allies may invoke Article 5 (21) of the North Atlantic Treaty to address hybrid attacks on any NATO member. They have set up counter-hybrid support teams which help allies prepare against and respond to hybrid actions. Furthermore, NATO’s hybrid analysis branch aims to improve situational awareness and analyse rising threats on a systematic basis, a view shared by the EU. Therefore, EU-NATO coordination to address hybrid threats has been strengthening since the first Joint Declaration in 2016, where 20 common measures out of 74 were dedicated to countering hybrid threats. In addition, as some Western Balkan countries are NATO allies and several are candidates for both EU and NATO membership, systematic and structural initiatives to fight hybrid actions undermining the perception of the EU and NATO in the region are critical not only for European and transatlantic, but also transnational security.

While the EU’s and NATO’s mandates and toolkits differ, their presence in the region is complementary and rooted in close cooperation (22). Interventions in Bosnia and Herzegovina are an example of the ‘single set of forces’ principle between the EU and NATO, showcasing both actors’ practical cooperation. Recently renewed for another 12 months, EU military operation Althea has been deployed following the departure of NATO’s peacekeeping mission and demonstrates complementary roles and adaptation within the international community. The NATO forward presence in Bosnia and Herzegovina is also essential, especially when it comes to military and cybersecurity training exercises. NATO and the EU both use these as tools to engage with civil society and policymakers on the ground and build up their level of engagement in various initiatives (23). This increase in operational cooperation has led to the creation of permanent military liaisons in both organisations to facilitate future cooperation (24). Moreover, in Kosovo, NATO’s KFOR mission also plays an essential role in maintaining regional peace and security, together with the EU’s EULEX mission.

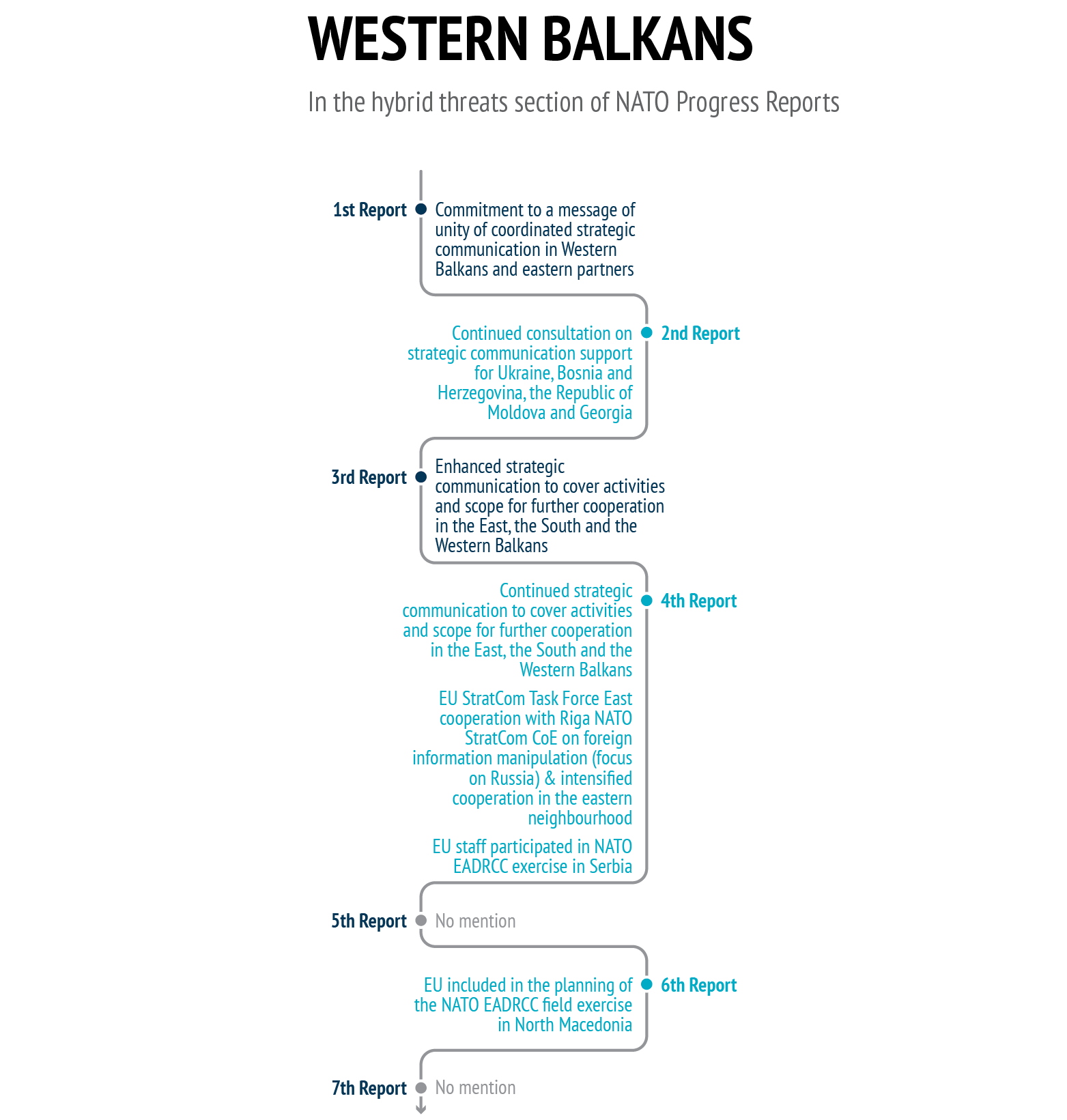

The enhanced cooperation between the EU and NATO in the region has created closer ties, allowed for more systematic exchanges of information and good practices and contributed to stronger, tangible actions in the field to build resilience. The EU and NATO have thus developed strategies for countering hybrid threats specifically tailored to the Western Balkans (25). These range from concerted messaging to political and military cooperation on the ground and EU staff participating in NATO Euro-Atlantic Disaster Response Coordination Centre (EADRCC) exercises in Serbia or North Macedonia (26). Thanks to these initiatives, both organisations now have a better understanding of the nature of the threats and threat actors, and their views have further converged (27).

The EU and NATO are both very active in strategic communication, whether on the political or operational level (28), especially when countering disinformation in the region. For example, the European External Action Service set up the Strategic Communication Western Balkans Task Force in 2017 which closely cooperates with NATO. Cooperation in this domain has intensified since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, during which time Russia has drastically increased information manipulation. Despite enhanced efforts, the differing or often unfavourable perception of both actors in the region remains an obstacle to fully interoperable EU-NATO cooperation, especially in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. While both the EU and NATO have increased their funding and workforce to debunk falsehoods and develop narratives highlighting the benefits they can bring to the region, there is a different historical legacy and societal perception of their roles in the region.

The EU and NATO have an important role to play in terms of building resilience, specifically in the Western Balkans where this is needed. At the inter-institutional level, staff-to-staff talks between both organisations have intensified and remain a useful tool when cooperating at the political level is not possible. Staff exchanges and activities such as workshops and cross-briefings, the EU-NATO Resilience Workshop or the NATO-hosted workshop on 5G networks and foreign direct investment (29) have contributed to fostering common situational awareness on hybrid threats. An important milestone was reached in 2020 when NATO international staff were included in the International Cooperation Space on the EU’s Rapid Alert System (30), which is also a helpful tool to increase awareness on hybrid threats in the Western Balkans.

However, a critical issue limiting deeper EU-NATO cooperation in countering hybrid threats and information sharing, remains the organisations’ divergent membership base and their respective limited mandates. Although there is a substantial overlap – with 21 ‘double-hatted’ countries (31) – some EU countries are not NATO members and vice versa. As tackling hybrid threats is neither a purely military or civilian, political or economic endeavour, a joint framework providing for common situational awareness would prove useful in the region, emphasising calls for a whole-of-society approach and mobilising both organisations’ toolboxes to bolster cooperation and elevating it to a new level. Nevertheless, there is currently no joint EU-NATO threat assessment (32), which would facilitate a common awareness of potential rising hybrid threats and allow for better and more synchronised responses from the EU and NATO.

EU – NATO cooperation to enhance stability in the Western Balkans

Implications for the role of the EU and NATO

Often referred to as Europe’s ‘soft underbelly (33), the Western Balkans could turn into a new source of unrest in a continent already unsettled by the outbreak of the war in Ukraine. Against this backdrop, the EU and NATO may need to strengthen their coordinated involvement in a more systematic and institutionalised way. The war in Ukraine has relaunched questions about the future of Euro-Atlantic integration (34).

First, several security-related policies and communications have enabled the EU and NATO to address hybrid threats at policymaking level in both EU and NATO Member States. Most recently, in the EU Security Union Strategy for the years 2020-2025 (35), the EU has laid out a toolbox to ensure security not only in the physical but also in the digital ecosystem. In the fourth progress report on the implementation of the EU Security Union Strategy (36), foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI) have received special attention due to the barrage of FIMI activities linked to Russia’s illegal war in Ukraine. In the Strategic Compass for Security and Defence (37) adopted in March 2022, the development of a broader EU Hybrid Toolbox was set as one of the important deliverables, to provide ‘a framework for a coordinated response to hybrid campaigns affecting the EU and its Member States and should comprise for instance preventive, cooperative, stabilisation, restrictive and recovery measures, as well as strengthen solidarity and mutual assistance’. While other objectives of the Strategic Compass include strengthening the ability to detect, identify and analyse hybrid threats, the central role given to the Single Intelligence Analysis Capacity and the creation of EU hybrid rapid response teams is instrumental in achieving these goals in supporting countering hybrid threats within Member States and partner countries, such as the Western Balkans.

Hybrid threats present a salient example of how exploiting vulnerabilities through various hybrid tools of interference in one country can have a direct impact on the security of others, regardless of national borders, thus becoming transnational threats. This is due to the interconnections and interdependencies of critical infrastructures, digital systems and public spheres. This negative spill-over effect across countries and regions continues to drive wedges within the international community and makes it difficult to attribute responsibility, as malign actors may attempt to deflect blame and avoid being labelled as the sole illegitimate aggressor in the conflict, using a spectrum of hybrid tools.

Second, numerous initiatives, such as joint training programmes for local media to counter disinformation and FIMI, require a formal request from the affected country. In this context, the negative perceptions of the EU and of NATO represent a concern for both organisations, especially in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, not least because of local and FIMI campaigns against both organisations. This phenomenon became evident during the pandemic, with Russia and China’s ‘vaccine diplomacy’ (38) used visibly to strengthen their geopolitical standing in the region to the detriment of Western countries. Furthermore, unlike Albania, Montenegro, and North Macedonia, Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina have not joined the EU in imposing economic sanctions against Russia over its invasion of Ukraine. This further emphasises the cleavages between pro-Western and pro-Russian narratives. However, it also provides an opportunity for the EU and NATO to counter disinformation through investments in public campaigns highlighting their accomplishments.

Finally, strategic partnerships and engagement with prospective candidate countries are key instruments for the EU and NATO to keep building stronger relations in the region. However, the long road to membership and the lack of major breakthroughs in the last couple of decades has led to ‘enlargement fatigue’. This adversely affects both organisations’ credentials as vital partners in the region to the benefit of other foreign actors. The Western Balkans are sensitive to promises from the West and close partners, which often are not fulfilled in a timely manner. Indeed, one of the most effective ways of countering domestic and foreign actors is ‘to match words with deeds’. This is especially necessary since the Covid-19 pandemic, during which foreign actors were quick to exploit the EU’s and NATO’s limited presence in the region and spread disinformation about the Euro-Atlantic commitment to the Western Balkans. Going forward, the EU and NATO need to re-engage with key stakeholders on the ground to foster closer ties and gain a better understanding of the evolving information environment and how to best counter hybrid threats.

A European way forward enhancing resilience and deterrence

Europe is at a crossroads with a full-scale war taking place on its doorstep. Enhancing resilience, defence and deterrence is among the most critical priorities in today’s type of warfare. Furthermore, to successfully counter malign interference attempting to weaken the EU and NATO allies’ capacities and credibility in the Western Balkans, both organisations aim to present themselves as viable alternatives and security providers to other external players. Also, both organisations seem increasingly willing to further integrate the Western Balkans within their structures. For example, North Macedonia and Albania started EU accession talks in July 2022 and Bosnia and Herzegovina was granted EU candidate status in December 2022. Furthermore, broader integration is also encouraged by the current security instability and the Balkan countries’ geographic, historical, economic and political exposure to Russia and to manipulation by other threat actors. The ambiguous nature of hybrid attacks requires a wide set of tools to find a tailored approach. Gradually combining EU and NATO instruments within their mandates may make it possible for the two organisations to coordinate their efforts to detect, prevent, deter or counter hybrid threats in the most effective manner.

First, a coordinated EU-NATO response needs to be supported by shared situational awareness and a concerted approach to detect common threats and develop focused strategies to counter them, proactively prevent and deter, or systematically build resilience against them. Initiatives such as more joint projects and training exercises on the ground could further strengthen EU-NATO cooperation in the region. However, considering the growing divergences between countries, a one-size-fits-all approach to the region does not seem as most effective. A tailored approach with specific responses to hybrid threats adapted to each country seems more promising to foster EU-NATO cooperation in the region.

Second, both organisations would benefit from having their affirmative narratives amplified by local actors to enhance credibility and trust. This may reinforce the Western Balkans’ desire and efforts to comply with accession criteria, which could counterbalance enlargement fatigue and possibly re-engage the Western Balkans in a more dynamic way, focusing on rule-of-law and governance reforms within the countries. One of the problematic issues, however, is Serbia’s and Bosnia and Herzegovina’s reluctance to align their foreign policies with those of the EU, as illustrated by their refusal to impose sanctions against Russia.

Third, maintaining a tailored coordinated approach also makes a difference when assessing the effectiveness of EU-NATO cooperation on the security front. The systematic adaptation of the EU and NATO’s postures is necessary to avert destabilisation in the Western Balkans. The decision to extend EUFOR Althea’s mandate and double its size has reassured the international community and shown where the EU’s and NATO’s priorities lie. NATO’s complementary efforts in Bosnia and Herzegovina are also encouraging, mainly the adoption of a ‘new defence capacity-building package’. Furthermore, closing the gaps between NATO’s and Bosnia and Herzegovina’s standards by increasing military engagement and the adoption of transatlantic values in the country is crucial for the region, whose stability depends on Bosnia and Herzegovina’s situation (39). Therefore, ‘political and military engagement leading to EU and possibly NATO membership for Bosnia and Herzegovina, will contribute to securing the Eastern flank of the Alliance’ (40).

Fourth, to counter FIMI and support independent and investigative media, the EU could provide more training courses, funding and help coordinating media and digital literacy efforts with local governments and civil society organisations across the region. One way to do it could be to engage Western Balkan countries more deeply in initiatives such as the European Digital Media Observatory, European media literacy weeks or the European Democracy Action Plan. On top of improving the image of the EU in the region, it could lead to more transparent media practices and ownership and help limit foreign and political influence.

Finally, there remains a high degree of polarisation within and between Western Balkan countries. Efforts through the European Political Community or the EU’s Global Gateway investment initiative (41) may help strengthen cooperation between the EU and the Western Balkans. Nevertheless, there is a growing need to address the potential overhaul of existing mechanisms, including provision of assistance and capabilities to the region, enhanced through political support, to demonstrate that the experience with Ukraine has proved instructive and may also be extended to the Western Balkans. On its side, NATO might envision revising its engagement programmes in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia, to ‘standardise its approach while [tailoring] its activities in each nation’ (42). It could aim at providing more coherent and effective paths to its partners aspiring for NATO membership or, as a first step, strengthen their partnerships with the Alliance (43).

Conclusion

The Western Balkans are of strategic importance to the EU and NATO who continue to join forces to help stabilise the region and counter rising hybrid threats. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, both foreign and local actors have continued to try hard to amplify anti-Western and pro-Russian sentiments in the region.

The EU and NATO have been increasingly engaged in the Western Balkans for the last 30 years and have sought to develop a tailored approach to the region, including in countering hybrid threats. Although their cooperation and respective capacities have grown, some domains would benefit from an intensified, more coordinated and targeted approach to bring their partnership to the next level. This is especially the case when it comes to establishing a common situational awareness and concerted responses and alerts to malign activities in the region. Furthermore, as both organisations’ respective mandates do not necessarily overlap, which allows for complementary approaches, it also makes it harder to fully engage with each other. A necessary step to successfully operate in grey areas such as hybrid threats, would be to enhance the sharing mechanisms of their respective toolkits to further increase interoperability. In addition, both organisations could engage more on joint exercises and simulations in all the Western Balkan countries by using forums such as the Hybrid CoE.

Going forward, the EU and NATO will need to further improve their image in the region and regain control of more affirmative messaging showcasing the valuable strides both organisations have made. Enlargement fatigue and economic, political, and other dependencies on third actors such as China and Russia need to be mitigated in a timely manner. The EU and NATO could play a critical role in facilitating necessary transformations and enhancing critical capabilities. Their political roadmap and third Joint Declaration present an opportunity to further define and strengthen EU-NATO cooperation in the Western Balkans. This is essential to effectively counter hybrid threats not only within the region, but also to prevent potential negative spill-over effects on EU and NATO security due to increasingly more interconnected critical infrastructures, public spheres, and geopolitical interests.

References

* The authors would like to thank Beatrice Catena for her dedicated research assistance.

1. North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, ‘Joint Declaration on EU-NATO Cooperation’, 10 January 2023, p. 2 (https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_210549.htm).

2. The European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats, ‘Hybrid threats as a concept’ (https://www.hybridcoe.fi/hybrid-threats-as-a-phenomenon/).

3. Faleg, G. and Kovalčíková, N., ‘Rising hybrid threats in Africa: Challenges and implications for the EU’, Brief No 3, Conflict Series, EUISS, March 2022 (https://www.iss.europa.eu/content/rising-hybrid-threats-africa).

4. In line with DG NEAR’s conceptualisation of Western Balkans in the latest EU Enlargement Package of 2022 (https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/%20en/ip_22_6082).

5. European Union and NATO, ‘EU and NATO Concerted Approach for the Western Balkans’, 29 July 2003 (https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/er/76840.pdf).

6. See for example, European Parliament, ‘Report on the 2021 Commission report on Bosnia and Herzegovina’, 21 June 2022, point 84 (https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-9-2022-0188_EN.html).

7. ‘Illicit Influence (Part Two) - The Energy Weapon’, Alliance for Securing Democracy, 25 April 2019 (https://securingdemocracy.gmfus.org/illicit-influence-part-two-energy-weapon/).

8. McBride, J., ‘Russia’s influence in the Balkans’, Backgrounder, Council on Foreign Relations, December 2022 (https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/russias-influence-balkans).

9. Weissman, M., Nilsson, N., Palmertz, B. and Thunholm, P., Hybrid Warfare: Security and asymmetric conflict in international relations, I.B. Tauris, London, 2021, p. 63, p. 132 (https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1547060/FULLTEXT03).

10. This designation is without prejudice to positions on status, and is in line with UNSCR 1244 (1999) and the ICJ Opinion on the Kosovo declaration of independence. Applies across the full text of this Brief.

11. Greene, S. et al., ‘Mapping Fake News and Disinformation in the Western Balkans and Identifying Ways to Effectively Counter Them’, European Parliament Directorate-General for external policies, February 2021, p. 36 (https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2020/653621/EXPO_STU(2020)653621_EN.pdf).

12. EUvsDisinfo, ‘Disinfo: having NATO in Kosovo is a risk for the population as the west is expert in creating conflict’ (https://euvsdisinfo.eu/report/ having-nato-in-kosovo-is-a-risk-for-the-population-as-the-west-is-expert-in-creating-conflict).

13. EUvsDisinfo, Disinfo: the West is using Kosovo to break Serbia’s ties with Russia and China’ (https://euvsdisinfo.eu/report/the-west-is-using-kosovo-to-break-serbias-ties-with-russia-and-china).

14. Kovalčíková, N., ‘What if…the Western Balkans turn away from the EU?’, in Gaub, F. (ed), ‘What If…Not? The cost of inaction, Chaillot Paper No 163 EUISS, January 2022 (https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/CP_172_0.pdf).

15. Lessenski, M., ‘How It Started, How It is Going: Media Literacy Index 2022’, Open Society Institute Sofia, October 2022 (https://osis.bg/?p=4243&lang=en).

16. In which the Serbian government owns a 58 % stake. Reuter, ‘Serbia’s Telekom prepares to issue $543 million Eurobond’, 12 April 2022 (https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/serbias-telekom-prepares-issue-543-million-eurobond-2022-04-12/).

17. Public Hearing of Special Committee on Foreign Interference in all Democratic Processes in the EU, including Disinformation (ING2), 27 October 2022.

18. European Union Institute for Security Studies, ‘The Western Balkans and EU-NATO cooperation: how to counter foreign interference and disinformation?’, Event report, October 2021 (https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/SI-EUISS-%20Hybrid%20and%20WBalkans%20-%20Final%20Report.pdf).

19. Čančar, I. F., ‘Rethinking NATO engagement in the Western Balkans’, NDC Policy Brief, NATO Defence College, June 2022 (https://www.ndc.nato.int/news/news.php?icode=1719).

20. Zamfir, R., ‘Risks and Vulnerabilities in the Western Balkans’, NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence, April 2020 (https://stratcomcoe.org/publications/risks-and-vulnerabilities-in-the-western-balkans/57).

21. The North Atlantic Treaty, April 1949 (hptts://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_17120.htm).

22. ‘EU and NATO Concerted Approach for the Western Balkans’, op. cit.

23. ‘Rethinking NATO engagement in the Western Balkans’, op. cit.

24. Ibid.

25. Slovenian EU Presidency, ‘Countering of hybrid threats requires both EU-NATO cooperation in Western Balkans’, Insight EU Monitoring, 25 November 2021 (https://portal.ieu-monitoring.com/editorial/countering-of-hybrid-threats-requires-both-eu-nato-cooperation-in-western-balkans/363806?utm_source=ieu-portal/feed).

26. NATO, ‘Progress report on the implementation of the common set of proposals endorsed by NATO and EU Councils on 6 December 2016’, 14 June 2017 (https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_2017_06/20170619_170614-Joint-progress-report-EU-NATO-EN.pdf); NATO, ‘Fourth progress report on the implementation of the common set of proposals endorsed by NATO and EU Councils on 6 December 2016 and 5 December 2017’, 17 June 2019 (https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_2019_06/190617-4th-Joint-progress-report-EU-NATO-eng.pdf); NATO, ‘Sixth progress report on the implementation of the common set of proposals endorse by EU and NATO Councils on 6 December 2016 and 5 December 2017, 3 June 2021 (https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2021/6/pdf/210603-progress-report-nr6-EU-NATO-eng.pdf).

27. ‘Risks and Vulnerabilities in the Western Balkans’, op. cit.

28. Zandee, D., van der Meer, S. and Stoetman, A., ‘Countering hybrid threats. Steps for improving EU-NATO cooperation’, Clingendael report, Netherlands Institute of International Relations, October 2021 (https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/2021-10/countering-hybrid-threats.pdf).

29. Ibid.

30. ‘Sixth progress report on the implementation of the common set of proposals endorse by EU and NATO Councils on 6 December 2016 and 5 December 2017’, op. cit.

31. Soon to be 23 with the accession of Sweden and Finland.

32. ‘Countering hybrid threats. Steps for improving EU-NATO cooperation’, op. cit.

33. Saric, D. and Morcos, P., ‘The War in Ukraine: Aftershocks in the Balkans’, Commentary, Center for Strategic and International Studies, April 2022 (https://www.csis.org/analysis/war-ukraine-aftershocks-balkans).

34. Ibid.

35. European Commission, ‘Communication on the EU Security Union Strategy’, COM(2020) 605 final, 24 July 2020 (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0605&qid=1675335663889).

36. European Commission, ‘Communication on the fourth progress report on the implementation of the EU security strategy’, COM(2022) 252 final, 25 May 2022 (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52022DC0252&qid=1675171183082).

37. European External Action Service, ‘A Strategic Compass for Security and Defence’, 21 March 2022 (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/strategic_compass_en3_web.pdf).

38. Juncos, A. E., ‘Vaccine Geopolitics and the EU’s Ailing Credibility in the Western Balkans’, European Democracy hub, Carnegie Europe, July 2021 (https://carnegieeurope.eu/2021/07/08/vaccine-geopolitics-and-eu-s-ailing-credibility-in-western-balkans-pub-84900).

39. ‘Rethinking NATO engagement in the Western Balkans’, op. cit.

40. Ibid.

41. European Commission, ‘Global Gateway’ (https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/stronger-europe-world/global-gateway_en).

42. Lord, W. T., ‘Time for a new approach?’, Per Concordiam, 25 May 2017 (https://perconcordiam.com/nato-in-the-western-balkans/).

43. Ibid.