Eight years after the revolution, Libya is in the middle of a civil war. For more than four years, international conflict resolution efforts have centred on the UN-sponsored Libya Political Agreement (LPA) process,1 unfortunately without achieving any breakthrough. In fact, the situation has even deteriorated since the onset of Marshal Haftar’s attack on Tripoli on 4 April 2019.2

An unstable Libya has wide-ranging impacts: as a safe haven for terrorists, it endangers its north African neighbours, as well as the wider Sahara region. But terrorists originating from or trained in Libya are also a threat to Europe, also through the radicalisation of the Libyan expatriate community (such as the Manchester Arena bombing in 2017).3 Furthermore, it is one of the most important transit countries for migrants on their way to Europe. Through its vast oil wealth, Libya is also of significant economic relevance for its neighbours and several European countries.

This Conflict Series Brief focuses on the driving factors of conflict dynamics in Libya and on the shortcomings of the LPA in addressing them. It shows how the approach ignored key political actors and realities on the ground from the outset, thereby limiting its impact.

Driving elements of the conflict(s)

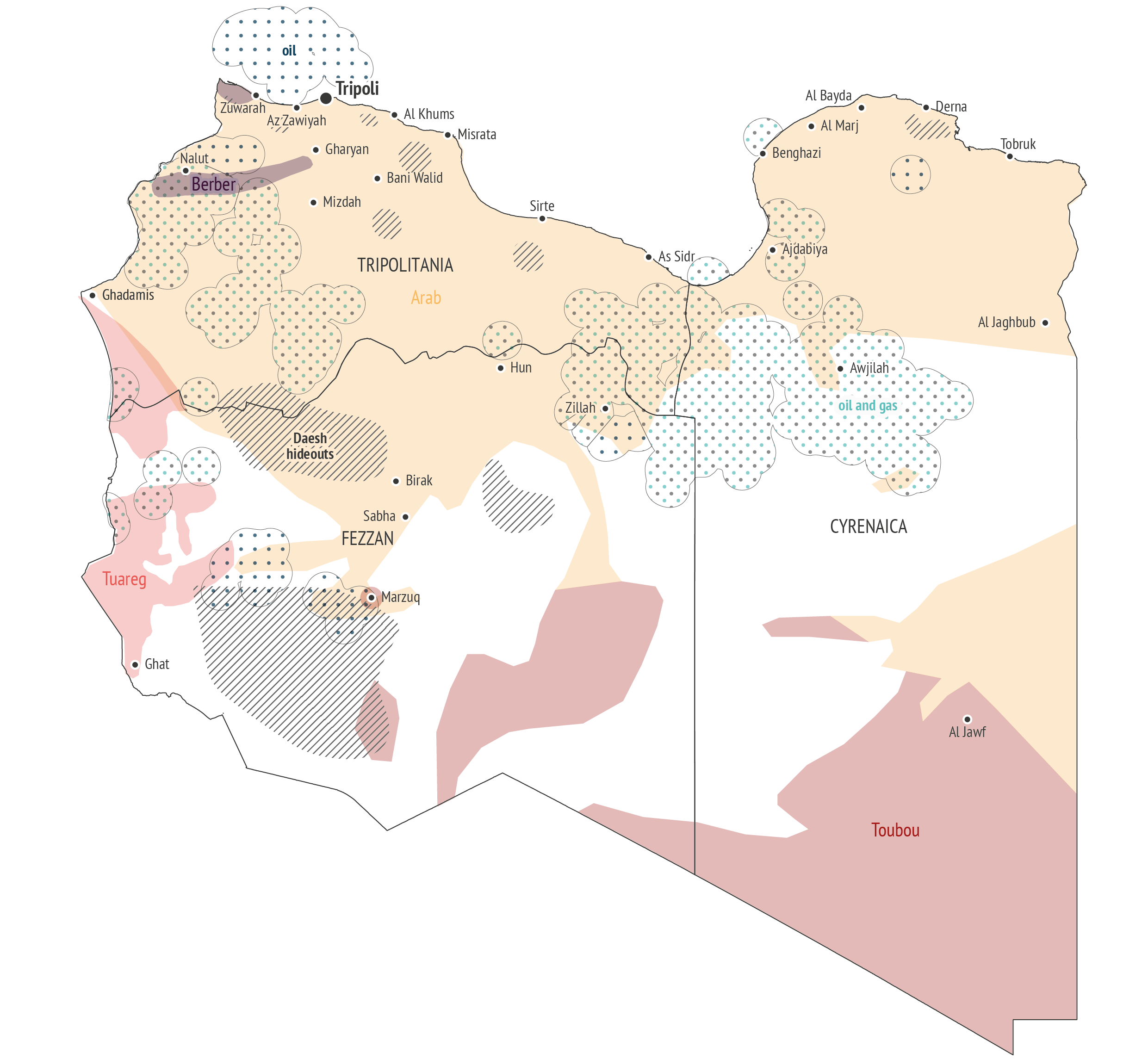

The struggle for resources, in particular oil, gas and freshwater, is one of the main driving elements of armed conflict in Libya. Most of these resources are located in remote areas controlled by the Libyan National Army (LNA). While the coastal population tends to claim that the resources belong to all Libyans, the tribes owning the terrain with the oil wells complain that they do not receive a fair share of what they perceive to be their wealth.4

Libya has experienced long-standing conflicts between Arab tribes and the original native population of the region (the Amazigh, Touareg and Toubou), as well as between settled peasant populations and semi-nomadic and nomadic tribes. Gaddafi used his knowledge of these localised conflicts (found especially in the remote south and the hinterland of coastal Tripolitania) to play tribes off against each other. These tribal conflicts continue to lead to bloody tit-for-tat violent episodes which are then worsened by the absence of law enforcement bodies and an independent judiciary.

The (at least perceived) neglect of the east by the post-revolutionary governments in Tripoli, combined with federalist and secessionist movements in Cyrenaica has led to a deep mistrust between Cyrenaicans and Tripolitanians. The polarisation between east and west has thus become a significant driving element of the conflict – this is also the case between Tripolitania and Fezzan, but to a lesser extent).

Libya – Regional borders, ethnic groups and natural resources

Data: PRIO, 2009; Natural Earth, 2019; GADM, 2019: ETHZ, 2018

The increasing political and economic influence of Islamists in Tripoli and within several militias alarms more secular Libyans. Islamists benefitted from the (questionable) narrative that they played an important part in the revolution and have managed over the years to obtain key positions in many important state entities, as well as in politics. Indeed, it was the radical Islamist assassination campaign in Benghazi against former regime loyalists, civil rights activists, Madkhali Salafists5 and security forces in 2013-14 that led to the launch of Marshal Haftar’s Operation Dignity. What started as a sort of self-defence campaign to free Benghazi from terrorist groups evolved quickly into a campaign against Islamists in general, ranging from political Islamists to dedicated jihadists. As many of those had close ties to western Libya, particularly to Misrata, the city became a party in the fight for Benghazi. Without logistical support and a steady flow of fighters to the besieged Islamists from Misrata, the struggle would have been shorter and less bloody (5,000 LNA fighters were killed). The battle also worsened deep-rooted grievances on both sides: Haftar, a hero in the eyes of many in the east, is strongly condemned by most in Misrata. The subsequent success of the LNA in its fight against Islamists in Derna, during which several prominent terrorist leaders were killed, further deepened this rift.

The control of criminal enterprises is another main driver of conflict between militias, in particular in the greater capital region: physical control over business premises, city quarters, airports, harbours and border crossing sites facilitates blackmailing and smuggling. Tripoli militias make hundreds of millions of dollars every year in the process, while rival groups from the outskirts and from neighbouring cities compete to get ‘their’ share. Similar conflicts occur over the smuggling of fuel, weapons, drugs and consumer goods between tribal groups in the border areas. The amended and extended European Union Integrated Border Management Assistance Mission in Libya (EUBAM Libya), supporting Libyan authorities in countering organised criminal networks and strengthening law enforcement institutions, is another indication of the severity of this issue.

Processes and bodies

Libya’s three historic regions – Tripolitania, Cyrenaica and Fezzan – developed more or less separately until the territory of today’s Libya was united through the Italian colonisation of 1911. The country’s first constitution (1951) was federalist and a strong rivalry between the three regions continues to characterise the country’s political scene.

The Libya Political Agreement (LPA), which provides governing principles and a framework for the stabilisation process, was signed on 17 December 2015* in Skhirat, Morocco, and endorsed by the UN Security Council (UNSC) on 22 December.** It is a contract between Libyan parties, which is to be facilitated and implemented under UN auspices. The LPA established a nine-member Presidential Council (PC) and a Government of National Accord (GNA), both headed by Prime Minister Fajez al-Serraj, as well as a parliament.

The House of Representatives (HoR) is Libya’s internationally recognised parliament, which was elected in June 2014. These elections were a major defeat for the Islamists (who had dominated the previous parliament) and were a key trigger for the subsequent outbreak of civil war. The HoR was confirmed by the LPA.

The Interim Government is the HoR’s associated government. It was internationally recognised until the LPA was signed.

The Supreme Court decision on 6 November 2014 was made under pressure from Islamist militias and ruled the June elections to be unconstitutional. Subsequently, the first interim parliament (which had been elected in 2012), the General National Congress (GNC) reconvened, albeit with only about one-third of its members. It appointed an Islamist-leaning National Salvation Government (NSG), whose importance faded away with the arrival of the GNA in Tripoli. The LPA assigned the Islamist dominated rump-GNC an advisory role as High Council of State (HCS).

UN Special Representative (UNSR) Ghassan Salame’s 2017 Action Plan sought to unblock the stalled stabilisation process and end the transition phase by modifying the LPA through negotiations between the HoR and the HCS. It aimed to have the already internationally recognised government endorsed by the parliament, convening an inclusive national conference, approving the draft of a new constitution by referendum and holding general elections. However, it is not politicians who are really in control of the country but the various military forces, militias and criminal gangs.

* Libya Political Agreement, Skhirat, December 17, 2015, https://unsmil.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/Libyan%20Political%20….

** United Nations Security Council, “Resolution 2259 (2015),” New York, December 22, 2015, https://unsmil.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/UNSC_RES_2259_Eng_1.p….

The LPA process: what went wrong and why?

There are several interlinked reasons why the LPA failed to stabilise the country. A major problem was the exclusion of several of the most important actors on the ground from the negotiations, namely the LNA, the Tripoli militias and the federalists. Consequently, those finally signing the agreement were representative of neither the reality of political and military power relations nor the wider population.6 The heads of the two rival parliaments rejected the deal immediately.7 Moreover, Serraj and several other PC-members were perceived to have been handpicked by the UNSR at the time, Bernardino Leon, and not by the Libyans themselves.8 All this led to a situation where the LPA as such is not accepted widely enough among Libyans.9

The GNA therefore suffers from a lack of legitimacy. In fact, it can even be argued that the LPA, under international influence, replaced a legitimate government with a new one without the consensus of local institutions. According to the LPA, both the agreement itself and the government must be endorsed by the parliament, but neither of these things ever took place. The main reasons for that are that the House of Representatives does not want to have the supreme commander of the armed forces appointed by the distrusted GNA and that most people in the east refuse to submit to a government which is de facto controlled by militias and gangs from Tripolitania. But even if the GNA were to have been fully recognised, things would not have changed much on the ground: for Serraj, in his long struggle for survival and influence among the militias in the capital, neither the parliament nor Haftar would have been of much help. This lack of a national legitimation also makes it very difficult to replace Serraj as it is unclear who could sack him; the UNSC which in effect enthroned him is probably neither a good nor a realistic option.

Since the revolution, Tripoli has been under control of several powerful militias. Yet ignoring this fact, on 30 March 2016 Serraj and several other members of the PC/GNA arrived in the capital, in a move strongly encouraged by UNSR Martin Kobler. While international media outlets and diplomats heralded the arrival as a major step towards stabilising Libya, on the contrary it contributed to deepening the crisis further.10 The GNA was delivered to a violent city without any means of protection of its own. Consequently, it has been fully dependent on the goodwill of local militia and gang leaders who have blackmailed the GNA (and allegedly even physically slapped Serraj several times). All of them are first and foremost interested in maintaining their own power and influence and most of the ‘pro-GNA’ militias will support Serraj only as long as they consider him a useful tool to pursue their own aims. Today, Tripoli is de facto ruled by four larger militias, two of them Islamist, who are deeply involved in criminal enterprises and in blackmailing the GNA. In this sense, Serraj and his government never ever enjoyed the freedom of manoeuvre to take action.

The lack of power of the GNA in Tripoli, let alone in wider Tripolitania, made any significant progress impossible. Serraj and his government have, with very few exceptions, no real possibility to influence developments on the ground. Many in Haftar’s camp do not consider Serraj a credible negotiating partner and portray him a hostage of the militias who surround him. While the UN and some European countries have organised meetings and signed agreements with Serraj (that he was not able to implement), the situation in the country has since deteriorated, particularly in the capital.

The grievances of the east were also not sufficiently addressed. As there is no transparency in the budget and spending processes, many in the east believe that they are once again being neglected by a government sitting in faraway Tripoli. Furthermore, they perceive themselves to be no more than idle bystanders while militias in Tripoli steal ‘their’ money generated from oil revenues and many complain that the UN is doing nothing to stop this.

Furthermore, the LPA process has failed to address the country’s basic economic problems. Although Libya’s most important economic organisations, the Central Bank of Libya (CBL), the National Oil Corporation and the Libyan Investment Authority recognise the GNA, Serraj has not been able to overcome Libya’s economic difficulties. The cash crisis – a combination of inflation, black market currency exchanges and a general lack of funds – continues. High subsidies for fuel and basic foodstuffs are a strain on the budget, while smuggling is an endemic problem costing the state several hundred million dollars a year. Moreover, corruption is entirely out of control:11 the CBL is still financing competing administrations in the east and west and pays former ‘thuwwar’ (270,000 ‘revolutionary fighters’ who are eligible for state payments, although only about 40,000 actually fought in the revolution) and militias as ‘official’ security forces. Tribes in the east and south therefore complain that revenues from oil extracted from their lands are used to finance those groups who are killing their sons.

Networks of competing Islamist groups, including the Muslim Brotherhood, various Salafists and the formerly al-Qaeda associated Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) wield significant influence behind the scenes, including over the GNA. They also lead to proliferation: indeed, most Libyans who end up part of terrorist organisations either in Libya or abroad started their ‘careers’ as members of one of the aforementioned groups. Altogether, the power of radical Islamists has been gravely underestimated and is likely to grow: as various radical Islamist groups are currently contributing significantly to the defence of Tripoli, it is highly likely that they will be able to expand their influence in the event that the LNA fails to take the city.

After its defeat in Sirte, Daesh was significantly weakened but not destroyed: it still commands 600-800 jihadists, mainly in southern Libya, and is conducting a low-level terrorist campaign with occasional high-profile attacks, including on the hydrocarbon industry. Worryingly, Libya is becoming ever more attractive for foreign Daesh fighters escaping from Syria and Iraq. Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) treats south-western Libya as a safe haven and both Daesh and AQIM use Libya as a springboard from which to operate throughout the region, representing a deadly threat for several countries.

Misrata

Misrata, a merchant city 180km east of Tripoli, fields Tripolitania’s most powerful military force. The city, which is a stronghold of the Muslim Brotherhood (MB), has an important harbour, but lacks both direct control of hydrocarbon resources and access to fresh water. Misratans have maintained strong relations with diaspora from the city living in the east of Libya for centuries, especially in Benghazi. In 2016, Misrata militias (with American air support) defeated Daesh in its stronghold Sirte after a seven-month battle. Due to several bloody incidents in the past (including the 2013 Ghargour massacre and violence against refugee camps in Tawergha), Misrata suffers from a very poor reputation in Tripoli, as well as with several other cities and tribes in Tripolitania. As a demonstration of this, up until Haftar’s attack on the capital, pro-GNA Misrata militias had largely lost their influence in Tripoli to local militias.

International interference

The failure of the stabilisation process in Libya must be seen in the context of competing interests of international actors, in particular of those openly siding with one of the conflict parties.

The key supporters of the anti-Haftar coalition are Turkey and Qatar, whose actions are primarily driven by support for political Islam and economic interests. Moreover, Turkey has very strong historic ties to western Libya, in particular to the city of Misrata: several hundred thousand people in Misrata, Tripoli and other coastal cities are Kouloughlis, descendants of Ottoman Turks who settled down with local women.12

Turkey’s troubled economy needs Libya as an export destination,13 while Turkish companies are seeking a major share in reconstruction efforts. The survival of the Islamist-influenced GNA and a leading role for Misrata are essential for Ankara’s economic interests in Libya and it is thus a staunch supporter of the LPA process. Turkey has granted permanent residence to several prominent former LIFG leaders, members of the Libyan Muslim Brotherhood, high-profile former Benghazi and Derna Shura Council fighters and Libya’s Grand Mufti, the Salafist Sadekh al-Gharyani. Their leverage is then utilised to pursue Turkish interests in Libya.

Both Qatar and Turkey are instrumental for the defence of Tripoli as they provide weapons and military equipment to several of the pro-GNA militias, in particular to those from Misrata. Most of this cargo arrives by ship or air in Misrata and is distributed from there. Allegedly, Turkey has also facilitated the transfer of Islamist fighters from Syria to Libya to contribute to the war effort. Ankara is even directly involved in the fighting though the operation of combat drone systems and by advising the military leadership of the anti-Haftar coalition.

While officially endorsing the LPA, the key allies of the LNA are Egypt, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Saudi Arabia and Jordan. Their involvement is mainly due to security-related interests, in particular counterterrorism and their opposition to political Islam, though they also have important economic interests. Egypt, the UAE and Jordan are supporting the LNA with military hardware and training, while Saudi Arabia and the UAE are vital for its financial survival: the LNA has almost no access to Libya’s oil revenues as all the payments end up at the CBL, which is under the control of the GNA. Today, most Arab states support the LNA, at least in a passive way. It was, for instance, telling that a request by the GNA’s foreign minister for an Arab League emergency meeting on Libya in mid-July was rejected14 (only Algeria, Qatar and Tunisia supported the request).

Egypt has played a particularly important supporting role for the LNA.15 The situation in the Arab world’s most populous country is characterised by a deep rift between secularists and Islamists, a weak economy and dozens of terrorist attacks which kill hundreds of civilians every year. Consequently, it wants to prevent a safe haven for terrorists emerging in Libya or an Islamist-dominated government sitting on its western border. Both certainly represent ‘red lines’: it can be expected that – if necessary – Egypt will also intervene directly with military means. Egypt’s important economic interests in Libya originate mainly from the some two million migrant workers who lived there before the revolution (now down to about 900,000), the investments of Egyptian companies and the country’s dire need for cheap energy.

Because of Egypt’s location as a neighbouring country, those backing the LNA are geostrategically in a better position than the other side. Logistical support can be provided directly without any risk of interception, while fighter aircraft are able to attack targets all over Libya from bases in western Egypt. Even ground forces could intervene easily, if required. Moreover, from Egypt it would be no problem to enforce a maritime embargo by controlling the sea between Crete and Libya; transport aircraft, drones or even fighters flying to Libya from Turkey could then be intercepted with ease. As Egypt (and the other supporters of the LNA) have all the means to realise these options, what will be implemented relies only on a political decision about how far Egypt is willing to go to protect its interests.

The anti-Haftar coalition is running a highly successful media campaign and effectively conducts lobbying efforts abroad, in particular in the UK, but also in the US and other countries, using its support for the LPA as a key tool. This works mainly through Libyan expatriates from Misrata, Tripoli and other cities in western Libya, who are often very well organised and benefit from excellent connections to some media outlets, think tanks and politicians. Unsurprisingly, networks of the Muslim Brotherhood in western Europe and in America are also supporting their ideological brethren in Libya; the GNA has even hired an American firm for the purposes of professional lobbying.

For its part, the European Union remains a key supporter of the UN LPA process. The EU mission Operation Sophia was meant to disrupt the business model of people smugglers operating out of Libya, but arguably became a feature of that model.16 According to critics, the European naval presence emboldened international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to operate off the very coast of Libya. Smugglers began to embark migrants in cheap and unseaworthy boats with the promise that they would be rescued.17 Since the re-opening of its embassy in Tripoli in July 2018, the EU is slowly raising its profile through several humanitarian assistance activities, which is important if it intends to assume a more active role in the future. For France and Italy in particular, Libya is of vital strategic interest due to economic, historical and security reasons.18 In line with its limited interests in Libya, the American involvement in Libya is centred on its lukewarm support for the UN-led process and counterterrorism efforts.

Despite these various interests in the situation in Libya, it would be wrong to blame the failure of the LPA on international interference. None of the driving elements of the conflict would have been defused were Egypt, Qatar and the others to have kept out: irrespective of the fact that before April 2019 the influence of LNA supporters on developments in Tripoli was next to nil, Serraj was unable to assert his authority in the capital. Libya is not to be viewed simply as the scene of a ‘proxy war’. Whether the engagement of the various states has had a stabilising or destabilising effect can be debated, but what is certain is that the mistakes made since the onset of the Skhirat negotiations could not have been corrected by these countries.

The flaws of the LPA process should have been acknowledged sooner and acted upon. However, the inertia of UN and international diplomacy, as well as the lack of consensus on a better alternative prevented a reset. Nevertheless, for those with strong interests in Tripolitania or in furthering political Islam, the LPA remains a means to a preferred end.

The LNA

The Libyan National Army (LNA), commanded by Marshal Khalifa Haftar, is the army of the HoR. As such it is not a ‘militia’, although many consider it to be one. Haftar refuses to recognise the GNA as long as it is not endorsed by the HoR. At the beginning of 2019, the LNA was in control of Cyrenaica and some parts of Tripolitania after defeating Islamist militias in Benghazi (2017) and Derna (2018). In January/February 2019, the LNA seized and stabilised the southern region of Fezzan using a combination of negotiations and decisive force. In early April 2019, Marshal Haftar launched a surprise offensive to take Tripoli, anticipating several militias to switch sides. However, this did not happen and the offensive failed at a high cost in human life. Thereafter, the LNA deployed large numbers of forces to the city and began a siege, while advancing slowly towards the centre. While 7,000-8,000 of Tripoli’s defenders are from Misrata, only 2,500-3,000 come from the city itself. There is credible information* that among the pro-GNA militias there are 450-600 hardcore Islamists, a number of whom are returnees from Syria, where they fought for the al-Nusra Front, an al-Qaeda affiliate.

* Author’s interviews with representatives of several stakeholders since April 2019.

Key conclusions and consequences

Some key conclusions can be drawn from the driving elements of the conflict in Libya and the failure of the LPA:

- The LPA process cannot be resuscitated and future stabilisation efforts should be based on an entirely new process.

- Deep mistrust, at times deep-rooted hate and protracted conflict characterises regional and sectarian relations in Libya.

- A country-wide reconciliation and a compromise about the way forward for a united Libya is not realistic at the moment.

- It is doubtful if Libya is currently ready to develop a final constitution.

- A fair distribution of the oil revenues must be ensured.

- Tripoli will be extremely difficult to stabilise, regardless of whether the city is taken by the LNA or not. It would be difficult to establish an assertive government there and protect it from its multitude of enemies in the city.

- The actions of the key international supporters of both sides are logical. For them, the conflict is not about values or ideals, but about concrete interests, some of them vital (like Egyptian security interests in eastern Libya) and therefore non-negotiable.

These conclusions lead to some consequences for the stabilisation process. Only a decentralised approach has a realistic chance for success. The intention must be to achieve a lasting stabilisation of Libya in its three historic regions. There is no need for a powerful central government, as most of the responsibilities should lie with the regions or former districts anyway.

Most importantly, for the time being an interim constitution should serve as a foundation for this decentralised stabilisation. An amended form of Libya’s 1963 constitution,19 which Gaddafi abandoned in 1969, could be used. Legally, it can be argued that the constitution is still in place, but it needs to be amended to ensure the fair distribution of the country’s oil wealth between the central government and the regions. Some provisions of the 1951 constitution, such as article 36 about central government powers and article 39 about provincial powers,20 should be also included. The head of state must either be a well-respected person (like the Libyan crown prince) or there should be a rotating chairmanship of a presidency council between the three historic provinces, although the un-subdivided body must be the collective head of state.

For now, the interim government cannot be based in Tripoli: until the security situation in the capital is improved, it should be temporary located in another city. If required and desired by the Libyans, an international protection force could secure a safe zone until the new government has sufficient forces of its own.

Stability also requires economic recovery. For Libya, this means stable oil exports at 2010 levels. If the distribution of oil revenues along the formula enshrined in the constitution can be guaranteed, the unhindered production and export of Libya’s hydrocarbon resources would be to the benefit of all.

However, economic security and regional stability also require that terrorism is tackled head on. Although it would be difficult to find a common definition for ‘terrorist’ in Libya, it is at least necessary to continue the fight against Daesh and al-Qaeda/AQIM. This needs to include the training of regional counterterrorism forces.

The way ahead

A lasting ceasefire in the fight for Tripoli is currently not realistic as both sides are convinced that the enemy would take advantage of the situation. Pro-GNA militias expect that the LNA would use such a lull to bring forward additional troops, refill its ammunition stocks (without the threat of Misrata’s air force) and relaunch the offensive when ready. The LNA is convinced that Tripoli will fall in a matter of weeks and that any ceasefire would allow the defenders to consolidate their positions. But even if Haftar is able to take Tripoli, the fight between the LNA and its opponents will be far from over.

However, after the battle for Tripoli has ended one way or another, a political solution based on the new military facts on the ground will be required. This political solution needs to centre on the outlined decentralised, bottom-up approach based on Libya’s old constitution. An interim constitution could be adopted by a national conference of tribal elders and elected local representatives, which would take much of the heat out of the discussion and allow local entities to focus on their own development.

Country-wide elections only make sense if most parts of the country, including the capital, are sufficiently stable to allow for a proper election process. If this is not the case, elections should be postponed or held only where possible, following a model similar to the elections to the US Senate, where one-third of the senators are elected every two years. The expertise of the EU when preparing for and conducting these elections could be very helpful.

Wherever there is a basic level of stability, fostering local security (including the creation and bolstering of local police forces), good governance and the provision of basic services should follow. A bottom-up rather than top-down approach (as has been tried up until now) is again recommended, in addition to a sustained fight against terrorism. There is vast experience within the EU in all these areas, which could be offered to the Libyans.

Only after a certain level of stability all over Libya is achieved, should the elaboration of a new, final constitution and country-wide elections take place. The aim should be to achieve this within a four-year stabilisation period. Again, the EU could assume a crucial role in supporting the process.

Without a new, successful initiative, the country will remain marred in chaos. There is a strong possibility that Libya could even disintegrate in an uncontrolled way, which would make it even easier for various radical Islamist groups to use parts of the country to expand their activities well beyond Libya’s borders. Ultimately, the stabilisation process must be conducted under close international supervision. It is here that the EU has the possibility to assume a key role in facilitating talks between the factions and supporting state building.21

References

* The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the EUISS or of the European Union.

1) See: UNSMIL – United Nations Support Mission in Libya, https://unsmil.unmissions.org/.

2) Noura Ali, “Tobruk’s parliament promotes Khalifa Haftar to Field Marshal,” Middle East Observer, 16 September 16, 2016, https://www.middleeastobserver.org/2016/09/16/tobruks-parliament-promot….

3) Jamie Doward et al., “How Manchester bomber Salman Abedi was radicalised by his links to Libya,” The Guardian, May 28, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2017/may/28/salman-abedi-manchester….

4) Ahmed Elumami and Ayman al-Warfalli, “Militia forces Libya’s NOC to declare force majeure on biggest oilfield,” Reuters, December 10, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-libya-oil-sharara/militia-forces-lib….

5) Followers of Saudi Sheikh Rabee al-Madkhali, who adhere to an ultra-conservative but politically quietist ideology.

6) “Details of signing the “Historic Agreement” in Skhirat,” Libya Prospect, December 17, 2015, https://libyaprospect.com/2015/12/details-of-signing-the-historic-agree….

7) Aziz El Yaakoubi, “Libyan Factions Sign U.N. Deal to Form Unity Government,” Reuters, December 17, 2015, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-libya-security-idUSKBN0U00WP20151217.

8) International Crisis Group, “The Libyan Political Agreement: Time for a Reset,” Footnote 6, November 4, 2016, https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/north-africa/libya….

9) While many supported a political accord in principle, there has been much dissatisfaction with the concrete agreement. See also: International Crisis Group, “The Libyan Political Agreement: Time for a Reset,” November 3, 2016, https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/north-africa/libya….

10) Wolfgang Pusztai, “The Failed Serraj Experiment of Libya,” Atlantic Council, March 31, 2017, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/the-serraj-experiment-….

11) Jimmy Armitage, “Libya sinks into poverty as the oil money disappears into foreign bank accounts,” The Independent, July 17, 2018, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/analysis-and-features/libya… and Transparency International, Libya, July 31, 2019, https://www.transparency.org/country/LBY

12) Abdullah Muradoğlu, “Kuloğlu’nun ahvâlini sorana..,” Yeni Safak, December 22 2015, https://www.yenisafak.com/yazarlar/abdullahmuradoglu/kulogluunun-ahvlin… and Can Haasu, “Kod adı Şakir,” Aljazeera, February 17, 2014, http://www.aljazeera.com.tr/blog/kod-adi-sakir .

13) “Libya and the Turkish occupier,” Al-Etihad, July 9, 2019 via Jerusalem Post, July 17, 2019, https://www.jpost.com/Middle-East/Voices-from-the-Arab-Press-LIBYA-AND-….

14) “Arab League rejects request for meeting on Libya,” Pan African News Agency, July 16, 2019, https://www.panapress.com/Arab-league-rejects-request-for--a_630597770-….

15) Wolfgang Pusztai, “Egypt’s interests and options in Libya,” The Arab Weekly, October 30, 2015, https://thearabweekly.com/egypts-interests-and-options-libya.

16) Author’s interviews with representatives of several stakeholders since the beginning of Operation Sophia.

17) See: House of Lords, “Operation Sophia: a Failed Mission”, London, 12 July 2017, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201719/ldselect/ldeucom/5/5.pdf.

18) Abdelkader Abderrahmane, “Eurafrique: New Paradigms, But Old Ideas, for France in the Sahel,” The Broker, November 21, 2018, http://www.thebrokeronline.eu/Blogs/Sahel-Watch-a-living-analysis-of-th….

19) The Kingdom of Libya, Constitution of the Kingdom of Libya (1951/63), Tripoli-Benghazi, 1963, http://constitutionnet.org/sites/default/files/1951_-_libyan_constituti….

20) The United Kingdom of Libya, Constitution of the United Kingdom of Libya (1951), Tripoli-Benghazi, October, 7, 1951, https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Constitution_of_the_United_Kingdom_of_Li….

21) Wolfgang Pusztai, “Libya and the Risk of Somalization: Why Europe Should Take the Lead,” ISPI, April 20, 2018, https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/libya-and-risk-somalization-….