In 2016, the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) signed a peace agreement after three years of negotiations and at least four failed peace talks since 1982. The implementation of the peace agreement has been monitored and verified by international actors with technical, humanitarian and financial resources to promote peacebuilding and reconciliation. This Brief examines the challenges of implementing the peace agreement and explores how the European Union can support the implementation process and reconciliation efforts in Colombia.

The Brief analyses first the state of play in the implementation of the peace agreement and its main challenges. Secondly, it presents an analysis of local-level violence. Thirdly, it highlights how peacebuilding and reconciliation efforts can mitigate local conflict dynamics. Finally, it concludes with policy implications and recommendations for supporting the implementation of the peace accord and shows how the EU can positively contribute to peacebuilding and reconciliation at the local level.

Gaps in implementation

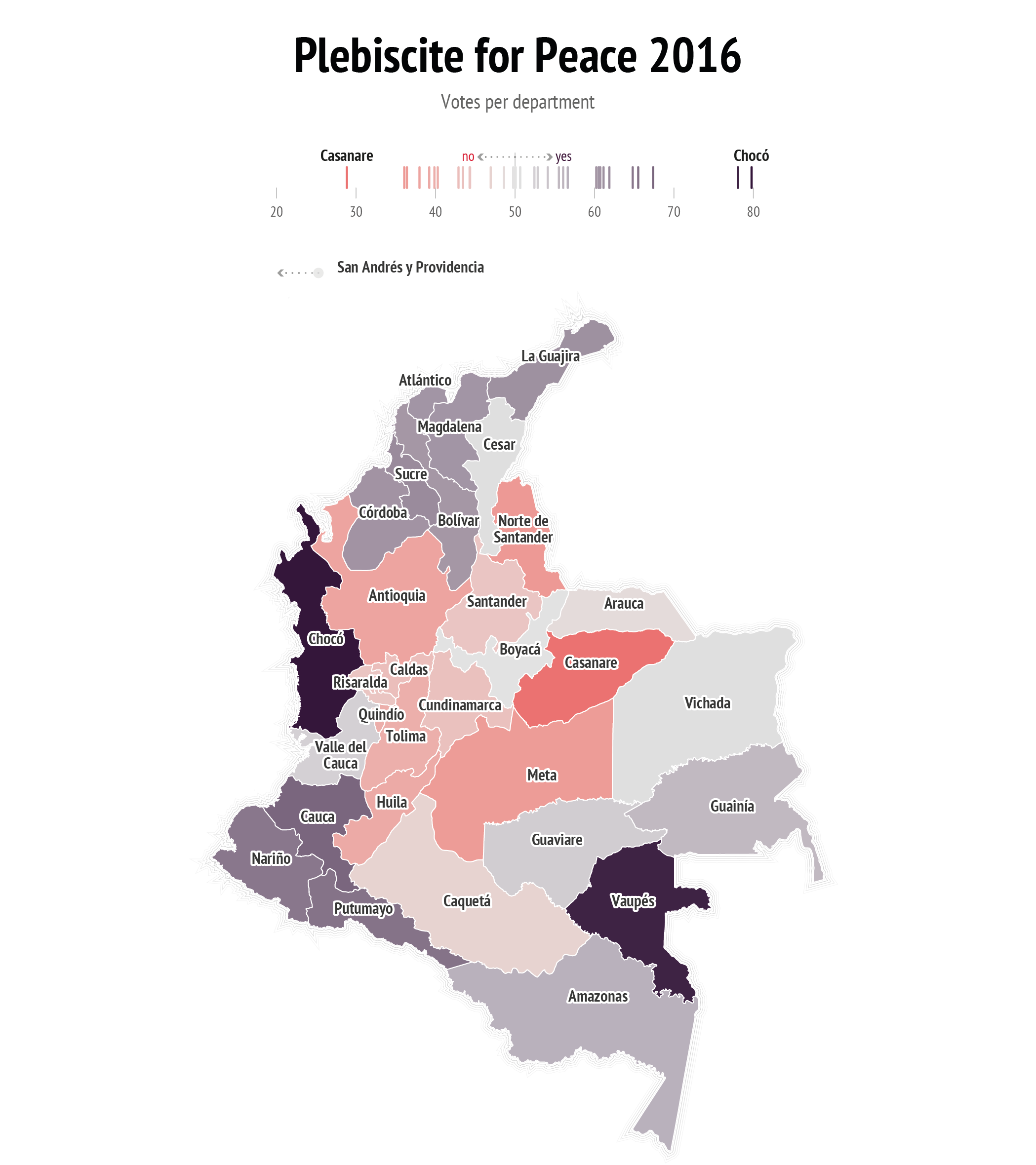

The implementation of the peace agreement can be credited with some positive aspects and outcomes. Firstly, the architecture of the agreement has transformed the government’s public policy approach, focusing on the local areas most affected by the violence of the conflict in a highly centralised country. Secondly, one of the main features of the process is that it promotes active participation by civil society to enhance the legitimacy of the peace accord and increase public confidence in it, especially at the territorial level. Thirdly, an inclusive perspective incorporates concepts of ethnicity and gender into the approach to peace and these feed into the implementation process. However, public perceptions concerning the peace agreement are still highly polarised, as demonstrated by the result of the plebiscite for peace that took place in October 2016 to ratify the accord (1).

The degree of polarisation in Colombian society shows that the implementation of the peace agreement faces many challenges. Overall, only 6 % of the goals and objectives set out in the peace accord were accomplished between 2018 and 2019.

Data: Registraduria Nacional del Estado Civil de Colombia, 2016; GADM, 2021

One of the main issues concerning implementation at the local level is the coherence between the original agreement and actual policy implementation (2). There is a clear discrepancy between the national government’s public discourse, in which it reassures international actors of its commitment to the peace agreement, and its record in actually implementing the provisions of the original accord, formulating and applying policies that do not correspond with the main points of the agreement. Additionally, coordination between the national and the local levels remains deficient (3). These negative aspects are reflected in the following main challenges for implementation at the local level.

Land reform and restitution

Concerningthefirstpointoftheaccord,‘comprehensive rural reform’, the government has been focused on the design of the multipurpose cadastre and Development Programmes with a Territorial Approach (PDET) (4) that were included in the National Development Plan, with the establishment of a land registry as a public service, and on the registration of one million hectares of public land in the National Lands Fund that has not been distributed. The implementation of the 16 Action Plans for Regional Transformation (Planes de Acción para la Transformación Regional – PATR) is one of the main challenges here, as to date progress has been made on the roadmaps for only three of these.

Political participation

Democratic participation at the local level and political interaction between the local and the national level needs to be expanded and institutionalised. There is a huge legislative challenge at this point regarding the approval of the key laws for institutional and democratic reform, which failed to pass in Congress in 2020, and the regulation of social protest and peaceful mobilisation.

Reincorporation of ex-combatants and security guarantees

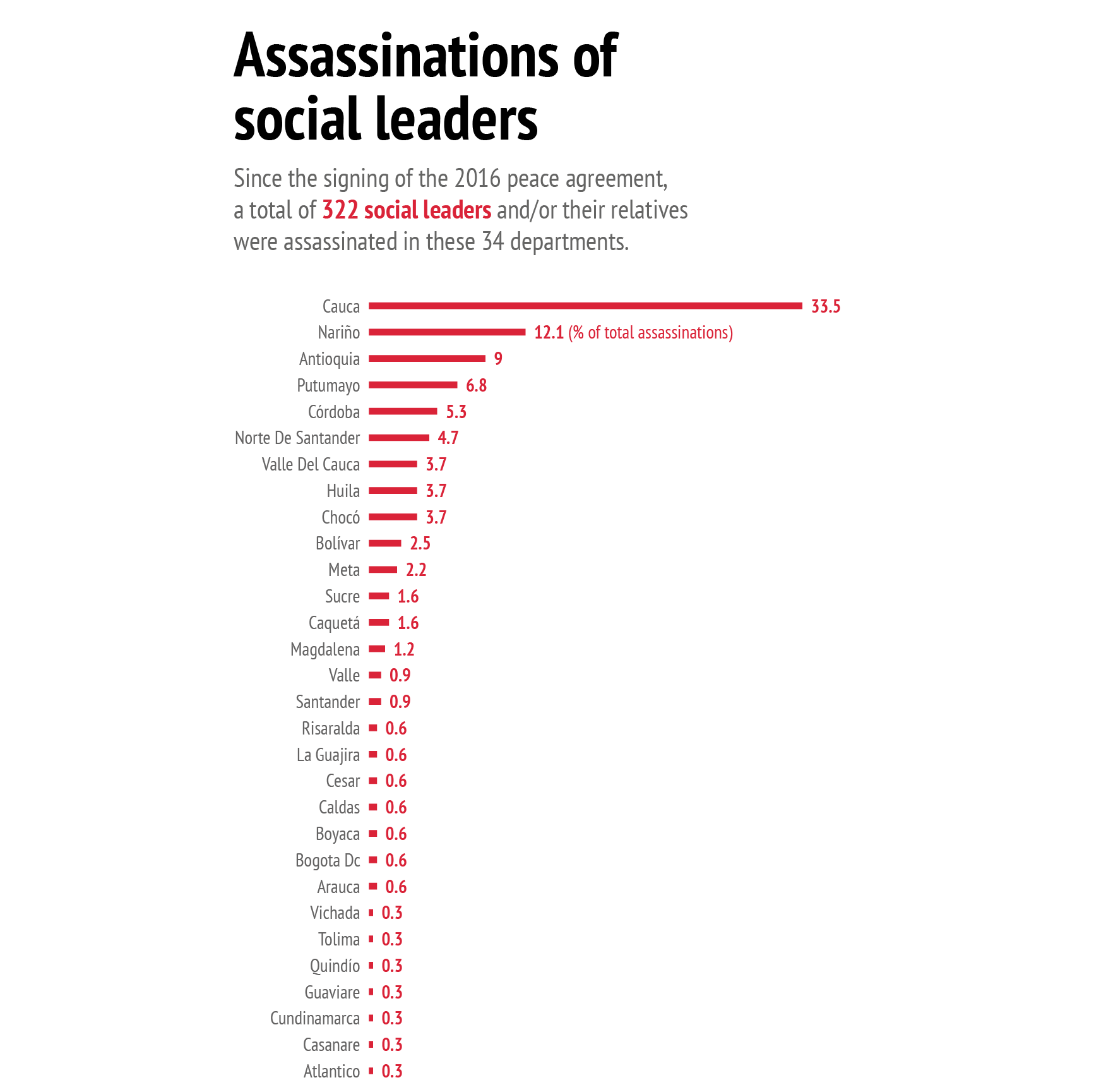

The disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) process has made progress through the commitment of ex-combatants, international actors and the government. Progress in this area has been achieved due to the approval of collective and individual projects, the reincorporation route and the maintenance of Territorial Training and Reincorporation Spaces. However, local security for ex-combatants is a key challenge: 2020 was the year in which ex-combatants experienced the most violence since the peace accord was signed in 2016, and this trend continues to increase. Data available from Indepaz, the Institute for Development and Peace Studies, records 322 social leaders murdered between 2016 and 2020 (5).

Substitution of illicit crops

The advances in this process have focused on technical assistance and nutrition security projects. However, violence against beneficiaries and low participation have increased communities’ distrust of the government. The implementation of crop substitution programmes has been delayed and not enough resources have been allocated to these projects. This has led to the increasing frustration of farmers who committed to substitution at the local level but who have not been provided with alternative means of subsistence or earning their livelihood (6).

Victims’ reparation and the protection of civilians

The Comprehensive System for Truth, Justice, Reparation and Non-Repetition seeks to advance the participation and inclusion of victims in the peace process using a gender and ethnic approach. The main challenges relate to the coordination between the national and the subnational level institutions, the prioritisation of collective reparation programmes and compliance with the Law of Victims. Advances in this field will help to reduce revictimisation of individuals and communities (7).

Civilians still suffer the consequences of violence at the local level in the post- agreement period.

Implementation and verification

This aspect has received significant financial support from the international community and the Colombian private sector with more than COP 290 billion (€63.5 million). However, improving the performance of regulatory implementation priorities remains a challenge (8). Significant amounts of foreign aid have been channelled to support the implementation of the peace process, but it is not entirely clear how these resources have been distributed in the framework of the National Development Plan, and there is clearly some discrepancy between the principles of the peace accord, to which the government has committed, and the programmes and projects carried out by the current government (9).

Challenges at the local level for peace and reconciliation

The main challenges hindering the implementation of the peace agreement are linked with dynamics of violence at the subnational level in the post-agreement period, where actors involved in the reconciliation process, namely victims, demobilised ex-combatants, civilians, civil society organisations and local government officials face insecurity and threats related to criminal violence, rearmament and drug trafficking. While the general indicators associated with violence from the armed conflict have improved in general terms, and some municipalities have been stabilised, civilians still suffer the consequences of violence at the local level in the post-agreement period.

Data: Indepaz, 2021

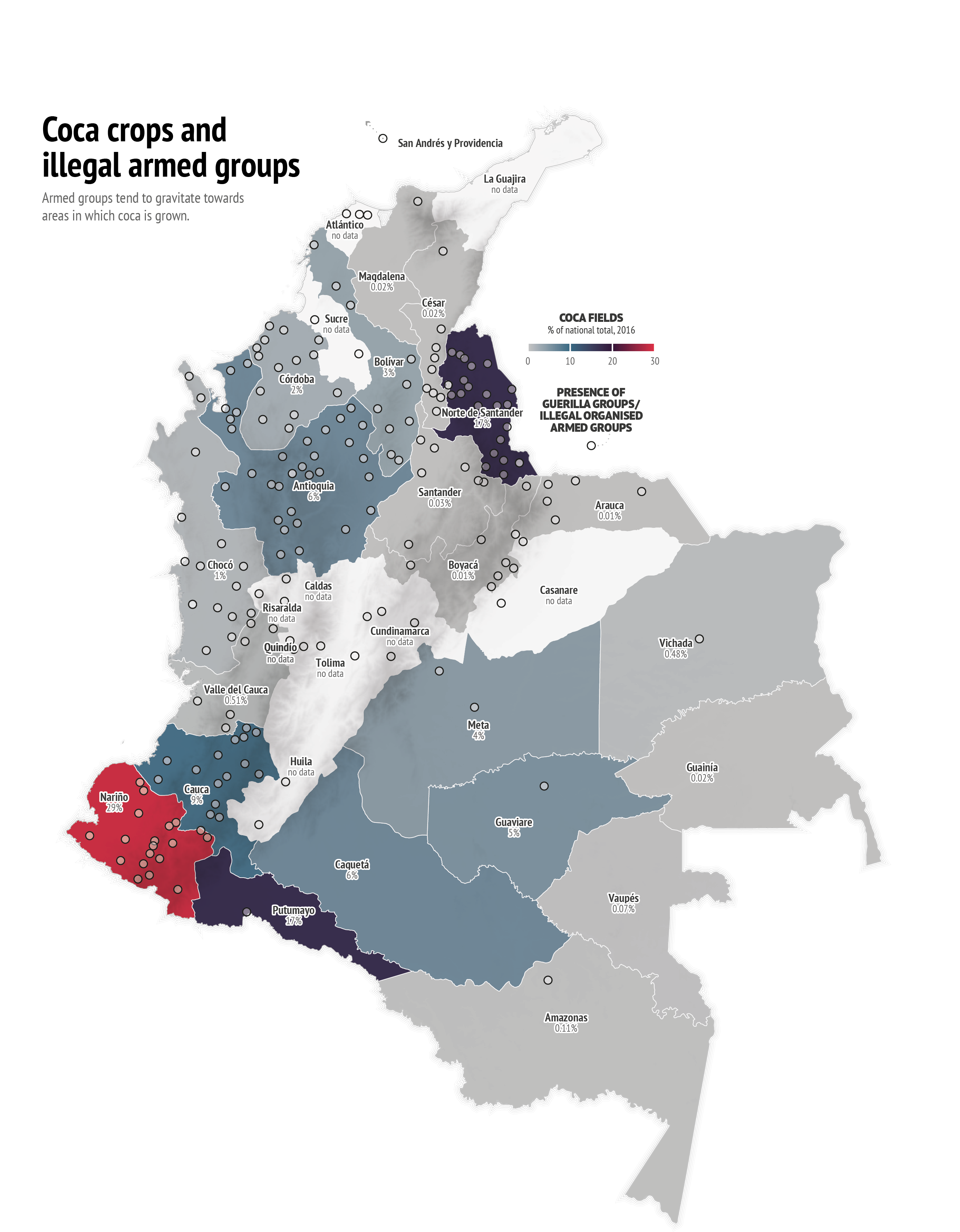

According to figures from the United Nations Verification Mission in Colombia (UNVMC), 251 ex-combatants have been assassinated since the signature of the peace accord (10), and around 3 000 of them have returned to illegal activities related to weapons, mining and drug trafficking. Illegal armed actors tend to gravitate towards areas where illicit crops are cultivated for narcotics and dispute control over these territories. Due to the growth of illegal armed groups in the areas formerly controlled by FARC, violence has increased (11). These groups include the National Liberation Army (ELN), new FARC dissidents who did not accept the agreement and illegal armed groups that operate as franchises associated with drug trafficking. These groups have filled the power vacuum that emerged after FARC’s demobilisation and operate in 123 municipalities where they pursue criminal activities (12). Reconciliation is defined as the restoration of non-violent relationships between former antagonists, meaning victims and former perpetrators, and rebuilding relations of trust with governmental institutions (13). Rebuilding this relationship of trust in post-conflict Colombian society includes the challenge of protecting civilians from violence. Without safety it is not possible to promote trust among victims, civilians and the demobilised population or between these actors and local government authorities: security is, therefore, a key factor for reconciliation.

Collective action to promote peace and reconciliation

Despite the violence that continues to affect various, mainly rural, parts of the country, Colombia has a tradition of peacebuilding and reconciliation at the local and community level. There are hundreds of locally-based organisations that promote peace at both the national and the local levels, as a collective strategy that civilians developed to protect themselves from violent armed actors and to find a neutral space amidst the violence (14). Indeed, 150 municipalities in the post-conflict period have experienced a return to peace and political violence has receded (15).

Apart from these initiatives and the work of victims’ organisations, there have been extensive mobilisations for peace in the country during recent years, with demonstrations in support of the peace process and the final accord regularly taking place from 2012 up until 2020, when street demonstrations (16) stopped due to the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic and the strict lockdown that was enforced in the country. The lockdown measures, with their restrictions on movement, have placed social leaders and vulnerable populations at increased risk of being targeted by militias and other armed actors (17). The increased mobilisation for peace in non-organised civil society shows the broad degree of support for the implementation of the final peace accord and public revulsion at the brutal methods of those intent on sabotaging the peace process, such as the widespread assassinations of social leaders, indigenous chiefs, farmers and ex-combatants, among others (18).

Civil society action and initiatives to promote peace and reconciliation have been based on five main strategies involving mobilisation and participation:

(i) the promotion of a peace culture through education and changing attitudes and behaviours; (ii) organisation and institutionalisation of the collective actors that support peace; (iii) community action that has an impact on politics: e.g. electoral participation, dialogue and collective negotiations; (iv) protests against violence perpetrated by armed actors and demands for guaranteed security and peace at the local level expressed through demonstrations, strikes etc; (v) pacific resistance to the violence committed by armed actors through the creation and consolidation of neutral zones of peace, peace communities and civil resistance campaigns. Actions for peace have been articulated in different forms at both the local and national level since 1978 (19). Civil society actors have tended to resort to this set of strategies increasingly over time, a phenomenon which has become more visible since the peace dialogues started and since the signature of the final accord. Clearly, channels of dialogue between civil society actors and governmental institutions need to be improved in order to promote mutual trust (20). The inclusion of non-organised civil society is essential throughout the whole process of mediation and conflict resolution, specifically at the local level, in accordance with the territorial approach.

The EU’s participation as a third party is key for safeguarding the implementation of the agreement at the local level and overcoming the limitations of the country’s centralised system.

Local peace initiatives and the organisations that deliver them are key components for the peacebuilding and reconciliation process (21). Such initiatives are more likely to take place under specific conditions (22), ‘such as at times of peace negotiations at the national level, which in the case of Colombia tended to coincide with the strengthening of the national peace movement’ (23). This shows that a long-term process of peacebuilding and reconciliation requires recognising and incorporating the perspectives and experiences of local actors. The implementation phase of the accord represents a crucial period to examine and articulate local peace and reconciliation initiatives in order to learn from the experience of local protagonists. In the Colombian context, it is difficult to talk about national reconciliation (24). Due to the ethnic, cultural, political and geographical diversity of the country, different processes of subnational reconciliation have been established since the 1980s, promoting the building and rebuilding of relations between former antagonists – ex-combatants, victims and civilians –as well as of their relations with governmental institutions (25). This a long-term process that started at the grassroots level as a result of local peace initiatives and the reconciliation communities that first built coexistence agreements between combatants and civilians, and between ex-combatants and victims progressively (26). The role of international state and non-state actors that have supported the process with foreign aid has guaranteed the presence of a third party between local communities and the government. The outcome of these interventions by international actors is in general terms positive (27). However, some studies highlight the need to clarify the role of these actors and their degree of intervention and participation in the peace processes, and in peacebuilding and reconciliation.

Post-agreement peace and reconciliation challenges - the role of the EU

The EU has built strong relations with Colombian civil society in an endeavour to transform the local dynamics of violence and conflict. Throughout the armed conflict and in particular since the 1990s, the EU has actively engaged with local civil society actors, strengthening links between civil society organisations and local and national government, and raising the visibility of the peace work that those organisations have developed over a long period in the national and international arena, in a country with a highly centralised political system (28). The EU’s role has been crucial in supporting civil society and promoting human rights protection at the local level, focusing its efforts on positive peacebuilding and addressing the root causes of the conflict (29). One of its main contributions has been the ‘peace laboratories’ (2002– 2012), with a total of €92 million distributed in 220 municipalities affected by the internal armed conflict, to foster activities to combat the transformation of the ‘causes of multidimensional violence’ (30). In parallel, the EU provided financial and technical support via the ‘peace and development programme in conflictive territories between 2004 and 2010. Afterwards, the EU promoted the ‘Regional Development, Peace and Stability’ programme between 2009 and 2015, and the ‘New Territories for Peace’ programme between 2012 and 2017. Currently, the EU supports the implementation of the peace accord in the framework of the European Trust Fund for Peace (31).

Data: Monitoreo de territorios afectados por cultivos ilícitos de Colombia, 2016; UNODC, 2020; GADM, 2021

The EU can continue to play a constructive role by monitoring the coherence between the key provisions of the peace accord articulated as state policy in the National Development Plan, its respective programmes, projects and activities, and the actual implementation of that policy, ensuring consistency between the mandate of the peace agreement and the concrete actions undertaken at the local level. Its participation as a third party and as a guarantor in the planning exercise at the Commission for Monitoring, Promotion and Verification of the Implementation of the Peace Accord (CSIVI) is key for safeguarding the implementation of the agreement at the local level and overcoming the limitations of the country’s centralised system (32). Linking the diverse agendas of international donors, the Colombian government and non-state actors and stakeholders involved in the process, such as victims, ex-combatants and civil society actors, is also a key element. Promoting and supporting the establishment (or re-establishment) of relations between these actors at the local level is an opportunity to strengthen the peacebuilding and reconciliation dynamics.

Land reform implementation

The effective participation of social organisations at the local level must be guaranteed in the implementation of the PDET road map. The financial stability of the PDET must also be ensured as a key point for the success of the implementation to include marginalised groups and reduce gaps. This is one of the most expensive parts of the accord that requires international support financially and technically (33).

Facilitating political participation at the local level

Democratic participation at the local level must be reinforced and stronger links forged between the local level and the national level. The territorial peace councils need to be strengthened and they require financial and technical support at the local level and enhanced interaction and coordination with the national level, facilitated by the National Council for Peace, Reconciliation and Co-existence (CNPRC)(34). Facilitating the participation of victims and ex-combatants in the implementation process is also crucial. Here the active, not just formal, participation of victims, ex-combatants and civil society is essential to ensure that they have real input in the formulation of plans, programmes and projects that is reflected in the fair assignation of budgetary funds. The role of the EU here is relevant as a guarantor of the transparency of this process.

ddR: reincorporation of ex-combatants and their security

The systematic assassination of ex-combatants must be stopped: this requires urgent attention from the international community to guarantee the safety of demobilised combatants and their families. Monitoring access to lands for productive agricultural projects is also a key aspect of this point (35).The aim is to improve security conditions and guarantees for the demobilised population and to link the interventions from the Comprehensive Security System (36), involving civil society participation (37). Rearmament dynamics should also be monitored. From a comparative perspective, the linkage between DDR and the peace implementation process is very relevant as observation of different conflict-affected countries over a 10-year period shows that high levels of implementation reduce the likelihood of rearmament over time. Conversely, weak implementation increases the likelihood that ex-combatants will rearm and resume paramilitary activity (38).

Crop substitution and development assistance

International donors should focus their efforts on technical and financial assistance for crop substitution and to guarantee the safety and participation of beneficiaries. Development-oriented initiatives should provide concrete alternatives enabling farmers to commercialise their legally produced crops at the local level. Safety is one of the main challenges for implementation: international actors should monitor the emergence of new violent non-state actors and their involvement in illicit crop production, human rights violations and violence against civilians, namely social leaders, beneficiaries of substitution programmes and ex-combatants.

Protection of victims’ and civilians’ rights

This point requires support from international actors to define a stable and clear budget to fund and deliver the victim reparation programme as set out in the Unique Register of Victims. The assassination of social leaders and activists also needs to be urgently addressed, by implementing local protection mechanisms aimed at reducing violence and threats against women, different ethnic groups, community leaders, the demobilised population and human rights defenders. Social leaders, indigenous chiefs, farmers committed

to the substitution of illicit crops, children, women and ex-combatants are targets of different armed actors. Dissident factions of FARC, the ELN, post-demobilisation armed groups, regular military forces, criminal bands and gangs are all actors that remain active at the local level and have continued to engage in violence during the Covid-19 pandemic. This matter must be addressed in line with the comprehensive and inclusive approach applied in the peace accord, understanding the relevance of guaranteeing civil and human rights in security-related operations and increasing the protection mechanisms for these vulnerable populations.

overseeing implementation and verification

As mentioned before, this is one of the most relevant challenges. At this point, the mediation of international actors is crucial to guarantee the coherence between the peace accord and its implementation via national development and planning tools (39). International actors, such as the EU, should guarantee the transparency of the implementation process.

Conclusions

Dialogue with the international community must promote mutual understanding and the alignment of agendas between the key actors of the peace accord and the dynamics of public policy implementation. The EU should participate in the formulation of public policy as a third party and as a guarantor of the implementation of the peace agreement, safeguarding the coherence between the accord and the implementation of national policies, ensuring that resources have been allocated as stipulated in the peace agreement and efficiently targeted at the populations for which they are designated, without technical or local distortions. In this regard, monitoring initiatives by civil society actors, victims and demobilised armed groups that follow and evaluate the implementation of the peace accord must be strengthened. The unity of objectives and the complementary constructive role that civil society can play in specific local contexts contributes to enhancing the strategic nature of the EU’s aid and creates capacities for citizens to build peace. This alliance between the EU and civil society actors translates into a counterweight to the forces seeking to derail the peace process and orchestrate a return to violence.

Finally, the main challenge for the local, national and international actors who support peacebuilding and reconciliation in Colombia is to build public confidence in the final accord and bolster its legitimacy, and to promote and strengthen the restoration of relations between victims and demobilised ex-combatants, as well as between civilians and democratic institutions. The continuation of programmes targeted at promoting positive peace is essential for this purpose, while the democratic participation of civil society is equally imperative to ensure the protection of civilians, human security and the consolidation of peace and stability.

References

(1) This map shows how urban areas, those that historically tend to be strongly influenced by the Conservative party and the Democratic Centre party, and some areas previously controlled by paramilitary groups, largely rejected the peace agreement. However, the capital, Bogota, where 56% of voters supported the agreement, was a striking exception. This outcome reflects the degree of polarisation in the country, with 49.49 % of voters supporting the agreement and 50.21 % rejecting it, according to data available from the National Registry Office of Colombia.

(2) In 2018 the implementation plan was approved, and the key points of the agreement were included in the National Development Plan and in local plans, with some technical difficulties and inconsistencies identified between the original agreement as a policy and its implementation. This plan will be implemented over the next 15 years, with elements reprioritised and updated frequently according to current needs

(3) Fundación Ideas para la Paz, Del capitolio al territorio – La implementación del Acuerdo de Paz en lo local: los desafios y las oportunidades, Bogota, 2019 (https://ce932178-d58f-4b70-96e7-c85e87224772.filesusr.com/ugd/883ff8_ ae12cdd588b64266bbebe841e15f065c.pdf).

(4) The Development Programmes with a Territorial Approach (Planes de Desarrollo con Enfoque Territorial) are 15-year planning and management instruments which aim to stabilise and transform the territories most affected by violence, poverty, illicit economies and institutional weakness, and thus achieve the rural development required by these 170 municipalities. See: OECD (https://www.oecd.org/cfe/_Colombia.pdf).

(5) Instituto de Estudios para el Desarrollo y la Paz (Indepaz), ‘Lideres sociales y defensores de derechos humanos asesinados en 2020’, 2020 (http://www. indepaz.org.co/lideres/); ‘La frágil paz en Colombia: a cuatro años de la firma de los Acuerdos con las FARC’, France 24, 2021 (https://www.france24.com/es/programas/reporteros/20210216-reporteros-acuerdo-paz-farc-colombia).

(6) Interview with a local expert, Bogota, August 2020.

(7) Fundación Ideas para la Paz, Del capitolio al territorio – La implementación de la paz en tiempos de pandemia : tareas urgentes, Bogota, 2020 (http://ideaspaz.org/media/website/FIP_CapitolioTerritorio_Vol8_InformeFinal.pdf); Unidad para la Atención y la Reparación Integral a las Víctimas, Registro Único de Víctimas, Bogota, 2020 (https://www.unidadvictimas.gov.co/es/registro-unico-de-victimas-ruv/37394).

(8) CINEP/PPP-CERAC, Quinto informe de verificación de la implementación del Acuerdo Final de Paz en Colombia para los Verificadores Internacionales, Bogota, 2019 (https://www.cinep.org.co/Home2/component/k2/670-quinto-informe- de-verificacion-de-la-implementacion-del-acuerdo-final-de-paz-en- colombia-para-los-verificadores-internacionales.html); Del capitolio al territorio – La implementación de la paz en tiempos de pandemia : tareas urgentes, op. cit.

(9) This incoherence is visible when contrasting the objectives and goals of the projects executed by the Agencia Presidencial de Cooperación Internacional (APC) and the Colombia in Peace Fund: victims’ organisations have reported how the money from this fund has in some cases been invested in random projects following reports from the APC and the National Audit Office. Interview with a local expert, Bogota, 2020.

(10) United Nations Verification Mission in Colombia, Report of the Secretary-General S/2020/239, 2020.

(11) After a peace process the likelihood of recidivism among demobilised ex-combatants oscillates between 15 and 20%. Around 14 000 FARC rebels demobilised collectively and 19 930 individually: the National Agency for Reintegration reports 2 761 demobilised ex-combatants absent from the reintegration process, representing 8.1 % of the total demobilised population (Source: http://www.reincorporacion.gov.co/en/agency/ARN%20Process%20 Figures/ARN_in_Numbers_March_2021.pdf).

(12) Fundación Paz & Reconciliación, Más sombras que luces, Bogota, 2019 (https://pares.com.co/2019/08/28/mas-sombras-que-luces-un-analisis-de-seguridad- en-colombia/).

(13) Rettberg, A. and Ugarriza, J. E., ‘Reconciliation: A comprehensive framework for empirical analysis’, Security Dialogue, Vol. 47, No 6, 2016, pp. 517–540.

(14) Kaplan, O., ‘Protecting civilians in civil war: The institution of the ATCC in Colombia’, Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 50, No 3, 2013, pp. 351–367.

(15) According to different sources, there are at least 1 900 social initiatives that promote peace, reconciliation and human rights, created between 1985 and 2016. These initiatives emanated from civil society and emerged in places where the armed conflict was most intense, as a reaction to violence from armed actors and the government’s lack of institutional capacity. See: Rettberg, A. and Quishpe, R., 1900 iniciativas de paz en Colombia – Caracterización y análisis de las iniciativas de paz de la sociedad civil en Colombia – 1985-2016, Bogota, 2017.

(16) Quinto informe de verificación de la implementación del Acuerdo Final de Paz en Colombia para los Verificadores Internacionales, op. cit; Del capitolio al territorio – La implementación de la paz en tiempos de pandemia : tareas urgentes , op. cit.

(17) Mustasilta, K., ‘From bad to worse? The impact(s) of COVID-19 on conflict dynamics, Brief No 13, EUISS, June 2020 (https://www.iss.europa.eu/content/ bad-worse-impacts-covid-19-conflict-dynamics).

(18) Interview with a local expert, Bogota, 2020.

(19) Quinto informe de verificación de la implementación del Acuerdo Final de Paz en Colombia para los Verificadores Internacionales, op. cit.

(20) Casas-Casas, A., Mendez, N. and Pino, J. F., ‘Trust and prospective reconciliation: Evidence from a protracted armed conflict’, Journal of Peacebuilding & Development, Vol. 15, No 3, 2020, pp. 298–315.

(21) Amaya-Panche, J. and Idrobo Velasco, J. A., Reconciliaciones y resistencias Modelos mentales y aprendizajes colectivos en la construcción de paz territorial en Colombia, Universidad Santo Tomás, Bogota, 2016 ; Arjona, A., Rebelocracy Social Order in the Colombian Civil War, Cambridge University Press, 2016; Valenzuela Grueso, P.E., ‘Neutrality in internal armed conflicts – Experiences at the grassroots level in Colombia’, PhD dissertation, 2009.

(22) Mac Ginty, R. and Firchow, P., ‘Top-down and bottom-up narratives of peace and conflict’, Politics, Vol. 36, No 3, 2016, pp. 308–323.

(23) Mouly, C., Belén Garrido, M. and Idler, A., ‘How peace takes shape locally: The experience of civil resistance in Samaniego, Colombia’, Peace & Change, Vol. 41, No 2, 2016, pp. 129–166.

(24) Chapman, A. R., ‘Approaches to studying reconciliation’, in van der Merwe, H., Baxter, V., and Chapman, A.R., (eds.), Assessing the Impact of Transitional Justice Challenges for empirical research, United States Institute of Peace, Washington D.C., 2009, pp. 143–172.

(25) Cortés, Á., Torres, A., López-López, W., Pérez, C. and Pineda-Marín, C., ‘Comprensiones sobre el perdón y la reconciliación en el contexto del conflicto armado colombiano’, Psychosocial Intervention, Vol. 25, No 1, 2016, pp. 19–25; Meierhenrich, J., ‘Varieties of reconciliation’, Law & Social Inquiry, Vol. 33, No 1, 2008, pp. 195–231; ‘Reconciliation: A comprehensive framework for empirical analysis’, op. cit., pp. 517–540.

(26) Kaplan, O., Resisting War – How communities protect themselves, Cambridge University Press, 2017; ‘Neutrality in internal armed conflicts: Experiences at the grassroots level in Colombia’, op.cit.

(27) Barreto, M., ‘Preparar el post-conflicto en Colombia desde los programas de desarrollo y paz: retos y lecciones aprendidas para la cooperación internacional y las empresas’, Revista de Relaciones Internacionales, Estrategia y Seguridad, Vol. 9, No 1, 2014, pp. 179–197; Castañeda, D., The European Approach to Peacebuilding – Civilian tools for peace in Colombia and beyond, Springer, 2014.

(28) In terms of the financial flows and the projects that international actors have supported since the beginning of the peace talks, Colombia has received USD 4.150 million in foreign aid since the signature of the peace agreements. In 2020, the UN multi-donor fund contributed USD 24.5 million to the Peace with Legality programme, while 43 % of the total foreign aid fund from the European Union to Colombia was designated for peacebuilding with USD 241.56 million disbursed between 2015 and 2018. The bulk of resources was invested in the areas most affected by the armed conflict, mainly the Pacific region and Middle Magdalena. These projects were mainly focused on the guarantee of victims’ rights (28 %), the consolidation of peace (25.5 %), governance (9 %) and human rights (8 %) (APC).

(29) Taborda, J. A. and Riccardi, D., ‘La cooperación internacional para la paz en Colombia: los casos de Estados Unidos y de la Unión Europea (1998–2016)’, Geopolítica(s), Vol. 10, No 1, 2019, p. 17 (https://www.nodoka.co/apc-aa-files/319472351219cf3b9d1edf5344d3c7c8/analisis_del_comportamiento_de_la_cooperacion_internacional_no_reembolsable_hacia_colombia_1.pdf).

(30) European External Action Service, ‘Colombia Los Laboratorios de Paz y los Programas Regionales de Desarrollo y Paz’, 2013 (https://eeas.europa.eu/ archives/delegations/colombia/documents/press_corner/2014/20140225_los_ laboratorios_de_paz_y_los_programas_de_desarrollo_y_paz_es.pdf).

(31) Agencia de Presidencial de Prosperidad Social de Colombia, Bogota, 2021 (https://prosperidadsocial.gov.co).

(32) Analysis from the World Bank reported that Colombia required at least 2.5% of the national gross domestic product to implement the peace accord. However, the current government invested just 0.8% of the national gross domestic product of 2020 for these purposes.

(33) Interview with a local expert, Bogota, August 2020.

(34) Contraloría General de la República de Colombia, Cuarto informe sobre la ejecución de los recursos y cumplimiento de las metas del componente para la paz del Plan Plurianual de Inversiones – Noviembre de 2016 a 31 de Marzo de 2020 – Énfasis Vigencia 2019, Bogota, 2020 (https://www.contraloria.gov.co/resultados/ informes/informes-posconflicto).

(35) Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies, State of Implementation of the Colombian Final Accord – Executive summary, 2019, pp. 1–4 (https://kroc.nd.edu/ assets/333274/executive_summary_colombia_print_single_2_.pdf).

(36) Following the Final Peace Agreement, the Comprehensive Security System is established in point 3.4.7.1.1. ‘High-Level Unit of the Comprehensive Security System for the Exercise of Politics (Instancia de Alto nivel del Sistema Integral de Seguridad para el Ejercicio de la Política). The High-Level Unit of the Comprehensive Security System for the Exercise of Politics (Agreement on Political Participation: section 2.1.2.1) shall develop and implement the following components of the Security System: Committee to promote investigations into crimes committed against people in the exercise of politics, taking into account women and the LBGTI community, as set out in section 2.1.2.1. subparagraph d. of the Agreement on Political Participation: A democratic opportunity to build peace.’ Programa Integral de Seguridad y Protección para las Comunidades y Organizaciones en los Territorios (https://www.peaceagreements.org/wview/1845/ Final%20Agreement%20to%20End%20the%20Armed%20Conflict%20and%20 Build%20a%20Stable%20and%20Lasting%20Peace).

(37) Centro de Pensamiento y Diálogo Político, La implementación del Acuerdo de paz durante el gobierno de Iván Duque – Tendencia a la perfidia y simulación, Bogota, 2019.

(38) State of Implementation of the Colombian Final Accord – Executive Summary, op.cit., pp. 1–4.

(39) Interview with a local expert, Bogota, August 2020.