You are here

The future of African food security

Introduction

A rising world population, a global pandemic, and a war in Ukraine combined with climate change impacts and increased inflation have disrupted food production, distribution, accessibility and affordability across the globe. Vulnerabilities in global food systems have been exposed, fuelling further concerns about resilience and sustainability in the food and agriculture industry.

Africa is well positioned to become the global breadbasket; with 60 % of the world’s unused cropland spread across the continent (1) that can be used for farming, it has the potential to emerge as a major food supplier. African governments are prioritising agriculture on their respective development agendas (2), and this shift has been supported by increased access to technological innovations and investments from the private sector and development partners. However, despite those positive developments, African food systems have been severely impacted by external shocks over the past 3 years (3). Why are African countries in danger of facing serious food shortages, despite years of policy reforms, investments and vast unexploited land resources? Why is the continent’s food system so vulnerable to global shocks? How can Africa strengthen its food systems with the clear objective of becoming a food exporter?

This latest Brief in the Imagine Africa series presents two scenarios as references for forward-thinking policy analysis and development priorities; one in which African countries continue to develop their agricultural systems without sufficient investment in skilled labour and another in which human capital is central to building sustainable and resilient food systems.

Scenario 1: Hungry for change and stability

It is 2030 and Africa is still unable to feed itself. The African continent’s annual food import bill has risen to $90 billion from $35 billion in 2022 (4) due to global food prices increasing and resulting supply and trade disruptions, which have been exacerbated by a growing population, rising unemployment and climate change shocks leading to further unrest, uncertainties, conflicts and inflation.

African agribusinesses are unable to increase their production capacities and are struggling to keep pace with local demands, let alone meet strict global market standards and tap into new market opportunities. The situation has become particularly dire in Central and East Africa. Promised to reap the benefits of the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) as well as the country’s integration into the East Africa Community (EAC) in 2022, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), which harbours the world’s third-largest population of impoverished people (5) and has 80 million hectares of arable land (6), has seen a sharp increase in political tensions, armed conflicts and security concerns across the country due to the failure of its strategy to bring down the cost of living by empowering local producers. In 2021 President Félix Antoine Tshisekedi declared that the country will prioritise agriculture over the mining sector (7) to transform its food system and increase its production capacity; however, the lack of an export-oriented agro-processing master plan means the agriculture sector is still unable to produce enough for local consumption in 2030. The absence of a modern food system as well as the country’s failed attempt to establish the Special Agro-Industrial Processing Zones (SAPZs) (8) programme because of limited skilled labour has resulted in the rise of the country’s youth unemployment rate.

The population is hungry and frustrated by the complacency of the governing elite and by the lack of development and socio-economic opportunities that a thriving agriculture sector would generate, leading to levels of anger and unrest last seen during the slow decline of the Mobutu regime in the 1990s.

Trends observed in the DRC have also unfolded across the continent in a wave reminiscent of the Arab Spring in the early 2010s, with a series of anti-government protests, uprisings, and armed rebellions spreading across much of Sub-Saharan Africa, especially in regions with similar food security challenges, such as the Horn of Africa and the Sahel. Some of these movements have been spearheaded by women demanding increased participation in economic activities.

African women have persistently remained an untapped asset in agriculture; women engaged in agribusinesses are constrained by limited access to productive resources, compared to their male counterparts (9) due to a lack of investment in human capital in terms of education and training. Unfortunately women farmers are facing even greater challenges than in the past due to their inability to adopt new innovative approaches. Women’s education is important for economic growth in countries where poverty and gender inequalities are pervasive. However low female enrolment in special training programmes in rural communities combined with their lack of access to higher education have led to further alienation of women in underdeveloped countries and resulted in strong anti-government protests.

While multiple projects have been launched over the years to strengthen local systems and institutions for service provision to women farmers, these projects have failed to yield the desired results due to the limited number of qualified women in businesses. There is a lack of dedicated training programmes, covering access to credit, financial skills and markets, that would transform women entrepreneurs into pillars of African food systems and agents for climate justice.

Scenario 2: A prosperous and skilled Africa

It is 2030 and investments directed to human capital development programmes have been integrated into a wider policy mix, including infrastructure development projects such as the SAPZs.

The SAPZs have achieved their objective by successfully integrating development initiatives designed to concentrate agro-processing activities within areas of high agricultural potential to boost productivity, and integrate production, processing and marketing of selected commodities (10). The SAPZs have attracted investments from private agro-businesses and financial institutions, by ensuring the provision of adequate hard and soft infrastructure such as roads, processing plants, storage facilities and training centres.

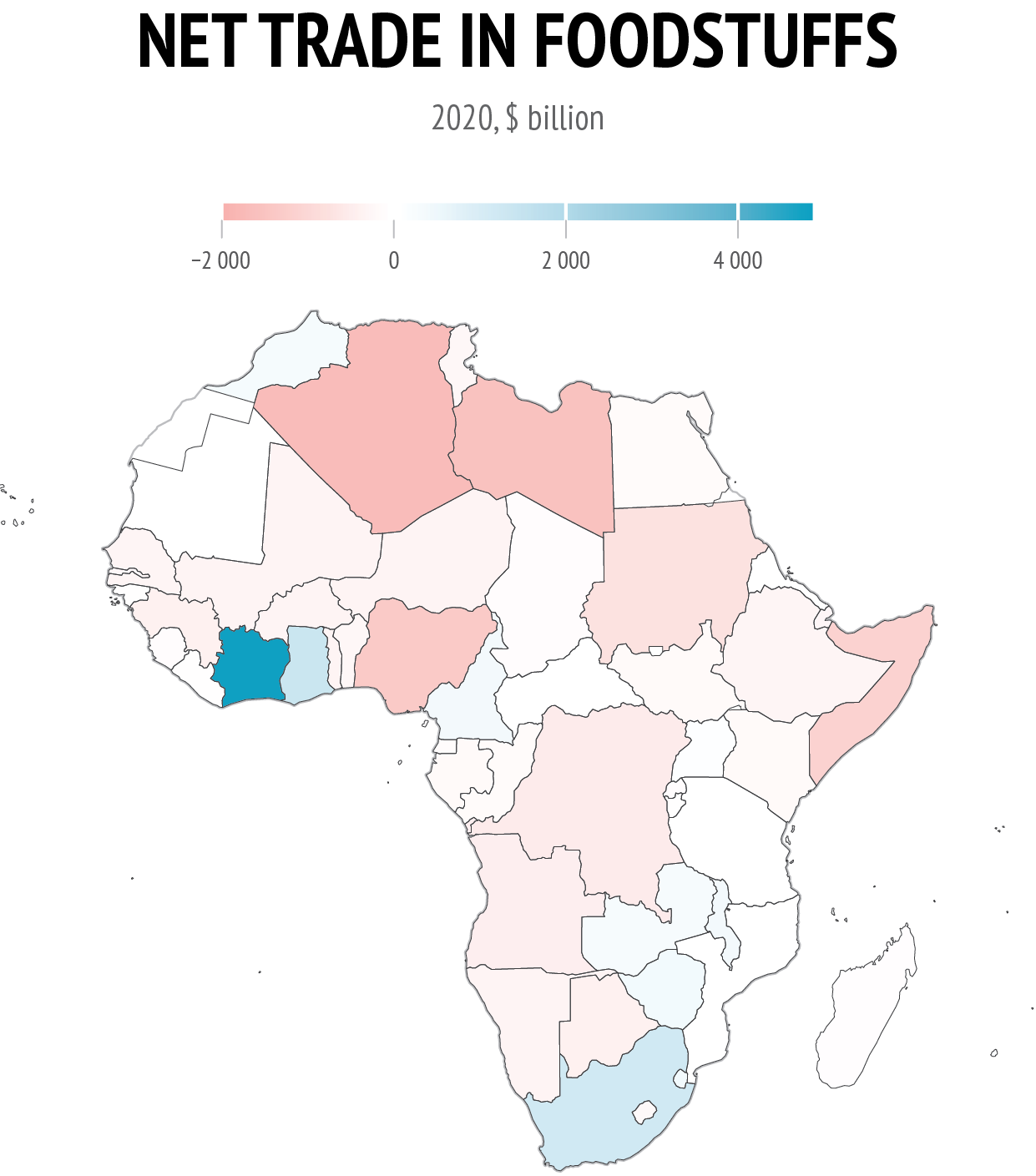

Data: Observatory of Economic Complexity, Foodstuffs, 2022; European Commission, GISCO, 2022

In Nigeria, for instance, the zones in 7 states (11) are contributing to the economic and social development of rural areas and improving the living conditions of the population through structural transformation of the economy and targeted skill set development. The Nigerian SAPZ programme has successfully reduced the country’s food import bill, and achieved the development of climate-adapted infrastructure for Agro-Industrial Hubs (AIHs) as well as the improvement of agricultural productivity and enterprise development to enhance agricultural value chains and job creation in the SAPZ Catchment Areas.

The SAPZs initiative is aligned with the African Development Bank’s Feed Africa Strategy for agriculture transformation as well as a trusted and successful ‘Made in Africa’ brand launched in 2023 by the African Union (AU) and developed by a qualified workforce. The continent has managed to build a strong brand, bolstered by increased productivity across leading commodities at an average of 2.5 % as a result of enhanced investments in technology and wider access to training, seen as critical drivers of agricultural development.

The years leading up to 2030 have seen an increased adoption of technology on African farms. Digital technologies associated with the Fourth Industrial Revolution (the broad shift toward greater machine autonomy, improved analytics, greater connectedness, andadvancedrobotics) have provided African agriculture with the tools to overcome productivity challenges. The shift has been achieved through dedicated training programmes; digital agriculture requires technological expertise, therefore technologically-driven economies on the continent have been able to unlock their full potential by connecting innovation, skills and value creation through dedicated national human capital development master plans.

Smallholder farmers are the backbone of African agriculture. However, they have been susceptible to climate and financial shocks in the past. The implementationofnationalhumancapitaldevelopment master plans have prioritised investments in the development of skilled smallholder farmers and improving the efficiency of their businesses, with a particular attention to women-led agribusinesses; the latter have been able to boost their incomes, spur their integration into regional and international value chains, and organise themselves into commercially sustainable cooperatives.

Policy action now

Whether African economies will be able to prioritise human capital in their development agendas or not will be determined by policy action taken now to address training and learning gaps. Arable land and investments must be supported by skilled labour. African countries unfortunately have traditionally lacked a clear human capital development plan that supports strategically identified sectors like food and agriculture. Africa is the world’s most youthful continent, and its young people are its most precious resource. Human capital will play a pivotal role in the transformation of African economies as well as the resilience and sustainability of its food systems (12).

The most realistic scenario for 2030 is a fragmented one, where the integration of human capital development in national master plans takes place in some countries while other African countries are still pursuing the development of their agricultural systems without sufficient attention to skilled labour. That said, the African continent has an opportunity to establish investment in human capital as a key priority on the continental development agenda, given the current global shocks. How might it go about achieving this?

First, the development of a ‘Made in Africa’ brand and label that upholds an agreed continental quality standard will require dedicated technical training in agricultural schools and programmes for the purpose of export. Additionally, the integration of young people into agriculture is key to achieve sustainable food production; increased investment in agribusiness incubation and accelerator programmes can create an environment for learning, growth and support.

Second, the majority of countries on the African continent will likely struggle to prioritise human capital development without financial support from external partners. To address this issue, the adoption of digital agriculture, combined with investment that is linked to technical assistance to enhance the relevant skillset, can not only fast-track the development of African agriculture but will also develop and upskill its workforce.

Third, by leveraging synergies between the private sector, AU and national governments to ‘build back better’. So far, the persistence of a gap between policy reforms, implementation and monitoring has jeopardised agricultural investments as well as the successful transfer of knowledge, technology and skills necessary to achieve a Zero Hunger continent by 2030.

How can Europe help? The AU-EU partnership can be leveraged in elevating the level of African skilled professionals and technical labour. In 2018, the EU had around €239 billion in foreign direct investment stock in Africa and provided €17 billion in Official Development Assistance (ODA) to the African private sector (13). In March 2022, the EU Commission committed investment funding for Africa worth €150 billion as part of the EU Global Gateway Investment Scheme (14). The EU could focus its support on:

- Policies for human capital development at a continental, regional and country level. The role of investment in human capital as a factor of growth and economic prosperity should be supported by relevant policies. These policies could be an extension of the Comprehensive African Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) (15), an initiative launched by the AU to boost agricultural productivity and achieve agricultural growth rates of at least 6 % per annum. Although some positive trends have been observed, there remains a lot of scope for improvement.

- Incentivise private investment in human capital through a dedicated AU-EU Agri-food Human Capital Development Fund (AHCDF). The AHCDF could be managed by the African Development Bank and modelled after the Agri-food SME Catalytic Financing Mechanism (ACFM) Special Fund which aims at de-risking the provision of financing agri-SMEs and catalysing additional private investment into the sector. The AHCDF could focus on developing human capital in food and agriculture while channelling additional private sector investment and support.

- Development of a ‘Made in Africa’ brand. The AfCFTA is a game-changer as it triggers regional integration of agriculture value chains. Successful integration requires qualified companies producing enough products for local and regional consumption that are able to compete against foreign products. The EU could facilitate the transfer of skills and technology to build trust in the ‘Made in Africa’ brand. This will require financial support as well as public relations campaigns to improve the perception of African-made products.

References

1. Oxford Business Group (OBG), Agriculture in Africa 2021, April 2021 (https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/sites/default/files/blog/specialreports/960469/OCP_Agriculture_Africa_Report_2021.pdf); OECD and FAO, OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2020-29, 2020.

2. The Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) – Malabo Declaration and Agenda 2063 aim to raise the share of national budgets devoted to agriculture and rural development to at least 10 %. The 13th session of the Ordinary Assembly of the African Union agenda focused on issues related to re-investing in agriculture for economic growth and food security. See: AfDB Feed Africa, Strategy for Agricultural Transformation in Africa 2016-2025 (https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/ uploads/afdb/Documents/Generic-Documents/Feed_Africa-_Strategy_ for_Agricultural_Transformation_in_Africa_2016-2025.pdf).

3. Stanley, A. and Kearns, J., ‘From war and inflation to food and cargo, charts chronicle volatile year’, IMF Blog, 30 August 2022 (https://www. imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2022/08/30/from-war-and-inflation-to-food- and-cargo-charts-chronicle-volatile-year); Kammer, A., ‘Europe must address a toxic mix of high inflation and flagging growth’, IMF Blog, 28 April 2022.

4. ‘Why is Africa importing $35bn in food annually? AfDB boss asks’, AfricaNews, 21 April 2017 (https://www.africanews.com/2017/04/21/why- is-africa-importing-35bn-in-food-annually-afdb-boss-asks//)

5. The World Bank, ‘Overview – The Democratic Republic of Congo’(https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/drc/overview).

6. ‘DR Congo investment summit to raise over US 10 billion’, The Exchange, 24 June 2022 (https://theexchange.africa/countries/dr-congo- investment-summit/).

7. ‘RDC: Félix Tshisekedi appelé a matérialiser sa vision de “la revanche du sol sur le sous sol”’, Le Quotidien, 15 August 2021 (https://lequotidien.cd/ rdc-felix-tshisekedi-appele-a-materialiser-sa-vision-de-la-revanche- du-sol-sur-le-sous-sol/).

8. IFAD, ‘Special Agro-Industrial processing zones Programme’ (https:// www.ifad.org/en/web/operations/-/project/2000003342).

9. Njobe, B. and Kaaria, S., ‘Women and agriculture: The untapped opportunity in the wave of transformation’, Background Paper for the Feeding Africa Conference, 2015 (https://www.afdb.orgfileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Events/DakAgri2015/Women_ and_Agriculture_The_Untapped_Opportunity_in_the_Wave_of_ Transformation.pdf).

10. IFAD, ‘President’s report: Special Agro-Industrial Processing Zones (SAPZ) Programme’, Project ID: 2000003342, 30 December 2021 (https:// www.ifad.org/en/-/president-report-nigeria-2000003342)

11. AfDB, ‘Nigeria - Special Agro-Industrial Processing Zones Program – Phase I (SAPZ I) - Project Appraisal Report’, 23 December 2021 (https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/nigeria-special-agro-industrial- processing-zones-program-phase-i-sapz-i-project-appraisal-report).

12. Davis, B., Lipper, L. and Winters, P., ‘Do not transform food systems on the backs of the rural poor’, Food Security, Vol.14, No 1, January 2022 (https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12571-021-01214-3).

13. ESI Africa, ‘EU funding for Africa worth €150bn to boost post-pandemic growth’, 11 March 2022 (https://www.esi-africa.com/industry-sectors/ finance-and-policy/eu-funding-for-africa-worth-e150bn-to-boost- post-pandemic-growth/).

14. European Commission, ‘EU-Africa: Global Gateway Investment Package’ (https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/stronger- europe-world/global-gateway/eu-africa-global-gateway-investment- package_en).

15. NEPAD - CAADP Country Implementation under the Malabo Declaration. April 2016 (https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/31251-doc-the_ country_caadp_implementation_guide_-_version_d_05_apr.pdf).