You are here

The future of African migration and mobility

Introduction

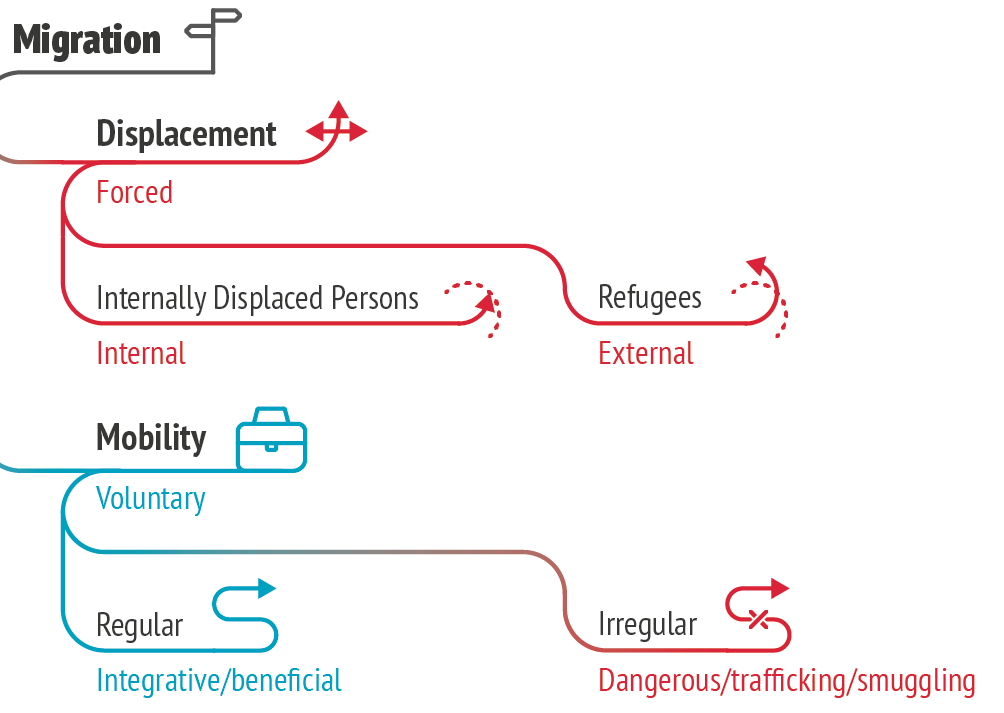

With Covid-19-related travel restrictions curtailed or lifted in most African countries, the issue of population movement and migratory flows – both within Africa and towards other regions, including the Middle East and Europe – has returned to the forefront of policy debates in the continent. The number of migrants is also increasing and may even exceed pre-pandemic levels. This is happening against the backdrop of profound economic, political, social, technological and environmental changes, including the impact of the war in Ukraine on African countries’ economic recovery and food security. These developments give rise to a number of questions: what are the likely changes in migration patterns, what will the geography of African migration look like by the end of this decade, and what are the repercussions for the partnership between the African Union (AU) and the European Union (EU)?

This Brief presents two foresight scenarios on migration and mobility for Africa. The first, an optimistic trajectory, envisages a continent on the move, with visa-free travel for all Africans, and expanded legal pathways to Europe and other destinations. Intra-African migration grows rapidly as free movement protocols are implemented, as does infrastructure development. The second is a pessimistic scenario, foreseeing a ‘contained continent’, where African citizens still need visas to travel to over 50 % of other African countries. More immigration restrictions have been imposed by both African and non-African states to limit the mobility of would-be irregular migrants, leaving Africans with no option but to resort to irregular migration routes.

Policy action discussed in the third section could facilitate or impede the emergence of either of the scenarios. The conclusion considers some policy implications, especially for the AU-EU partnership on migration and mobility.

Scenario one: A continent on the move

In 2030, the number of international migrants of African origin has doubled, reaching 80 million, mostly within Africa. It is a noteworthy change from a decade earlier, in June 2020, when 40.5 million African migrants were living outside their country – in another African country or outside Africa. In 2015-2020, 1.1 million Africans migrated outside their country per annum. This surge in the number of African migrants is predominantly attributed to the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and the emerging free movement regimes.

About 10 to 12 million Africans join the labour force annually, spurring mobility as young people migrate in search of jobs, education and better living standards. The AU and its member states issue passports to upwards of a billion people. The AfCFTA and its protocols are universally ratified and implemented, boosting trade by around 52 % (1). Africans, particularly in the service sector, enjoy free movement as part of the AfCFTA (2). With limited barriers to intra-continental movement, the 2030 Africa Visa Openness Report declares that the continent has achieved visa-free status for all Africans.

In its 2030 World Migration Report, the International Organizaton for Migration (IOM) reports that there has been a significant increase in migration within and outside Africa as well as a greater diversification of destinations. With increasing restrictive policies in traditional destinations such as Europe and new opportunities in emerging economies and trade routes, Africans are increasingly migrating to countries such as Turkey, China and South Africa for business, trade, study and employment. More alternative migration destinations offer more opportunities for work, income, business and remittances to families back home. Of the 281 million international migrants in 2020, 14.4 % were African migrants within or outside Africa (3). This constitutes an increase of only 0.3 % in five years, from 14.1 % in 2015.

The number of African migrants living outside their country of origin has almost doubled since 2010, reaching almost 41 million (4). In 2020, around 21 million of these Africans were living in another African country, while 19.5 million Africans were living outside Africa (5). 11 million, or 56.4 %, were residing in Europe, while 25.6 % (5 million) and 15.4 % (3 million) were living in Asia and North America respectively. By 2030, Africa will remain a continent of emigration, with 429 000 more Africans migrating out of Africa than the total number of immigrants it will host from other continents.

The number of African migrants attempting to cross borders irregularly within Africa and outside, mainly en route to Europe, has sharply declined, and the EU has expanded the opportunities for legal migration pathways (6).

Scenario two: A contained continent

It is 2030, and over the past ten years there has been little change in African population movement patterns. According to the African Development Bank’s Africa Visa Openness Report 2030, Africans need visas to travel to 55 % of other African countries, with 25 % requiring visas on arrival. (7) Since a decade earlier, in 2020, Africa has seen only a slight increase in intra-continental mobility. As a result, intra-African migration remains at the same level, or has not intensified significantly.

Many of the conflict hotspots and climatic shocks to which the continent is exposed remain significant sources of displacement, as the structural causes remain poorly addressed. Political instability and conflict are increasing, and displacement rates are rising.

In 2010, there were 10.5 million refugees and 14.7 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) globally (8); 2020 saw that number increase to 16 million refugees and 33 million IDPs (9). In 2030, the number of IDPs and refugees is still on the rise, but with the number of IDPs increasing at a much higher rate than refugees (10). Three-quarters of displaced people are IDPs. Neighbouring African countries host the overwhelming majority of refugees. This trend is highly likely to continue, given the impact of climate shocks and conflicts such as those in Ethiopia and DRC producing over 6 million IDPs and Uganda hosting 1.7 million refugees (11).

Demographic factors such as the fast-growing African population, coupled with a rapidly ageing population in the wealthiest economies, have increased the demand for labour. But in 2030, opportunities to migrate to Europe through regular channels are scarce and thus migrants continue to attempt the journey through irregular routes. Deaths of migrants during irregular migration, particularly at sea, rise sharply as rules are put in place to block rescue efforts. In 2030, more than 5 000 irregular migrants go missing or die each year travelling along perilous routes (12).

To further curb migration from Africa, European countries support local integration of refugees and irregular migrants within Africa in exchange for financial aid disbursed to states and non-state actors (13). Such restrictive measures in border areas or forced return schemes often lead to human rights violations, and arbitrary detention of migrants in unauthorised centres. Some European countries expand migrant schemes to send asylum seekers to African countries. EU Member States strive to increase the rate of return to North Africa and African countries from the 2020 rate of 21 % of total returns from the EU.

Impactful policy actions

Whether Africans will be on the move or whether their movement will be curtailed will be determined by policy action taken in four areas.

The first of these is urbanisation. Millions of young people are migrating to urban centres, searching for employment and a better life (14). With an average urbanisation rate of 4.1 %, Africa’s towns and cities will grow faster than any other urban centres in the world (15). The emerging African middle class will expand fast. Close to half of Africa’s 1.69 billion population settle in urban areas. These include the current mega cities (Kinshasa, Lagos, Cairo), and up-and-coming mega cities (Cape Town, Johannesburg, Dar es Salaam, Nairobi) (16).

The second one is connectivity. Infrastructure development in Africa, such as airports and sea ports, roads and railways, will also have a significant impact on mobility. Annually, an 11 % increase of young people connected via mobile telephones and the internet (17) is boosting the continent’s more technologically savvy and connected generations by millions. Mobile coverage is increasing, with 70 % of the population currently having access to mobile phones, while mobile internet penetration is 43 %, 23 % less than the global average (18). The current 520 million people with internet access (19) and the number of mobile internet users will rise to more than a billion by 2030 (20).

The third one is climate. The impact of climate change on mobility and displacement is growing, revealing complex interplays between unpredictable weather patterns, water insecurity, food insecurity and migration. Africa is disproportionately affected by extreme weather events, particularly by flooding and drought. The 2021 Climate Change Vulnerability Index (21) shows that five of the ten countries most threatened by climate change are in Africa. Natural disasters destroy livelihoods, forcing many people to move, primarily to nearby places. Disaster-related events have further exacerbated existing crises, particularly in fragile states.

The fourth one is conflict. Violence by state and non-state armed groups such as Boko Haram militants in Nigeria, and al-Qaeda affiliate al-Shabaab in Somalia continues to be a main cause of mass displacement. Governance failure is the primary driver of displacement due to conflicts, which compel people to move, or disasters, where governments are unable to effectively predict, prevent, respond or adapt to shocks. Libya is a good example of how stability and state fragility hamper the effectiveness of migration governance. Libyan state fragility allows opportunistic non-state actors to operate relatively freely with little accountability.

To address these challenges, transformation has to outpace crises in Africa. For instance, a highly connected, mobile and vocal but unemployed young population, especially in urban areas, may mean more migration, both regular and irregular. Wage differentials between countries within Africa and beyond will determine the extent of migration and the risks migrants are prepared to take. Expanded employment opportunities through integration and legal pathways, better service delivery, and enhanced stability may contribute to reduce irregular migration through dangerous routes.

Conclusions

The most realistic scenario for 2030 would be in-between the manifestly best and worst scenarios presented above. African states, the AU and Regional Economic Communities (RECs) are likely to implement the free movement regimes at a different pace, leading to modest gains in the free movement of Africans within Africa. The continent will likely continue to suffer from the gap between policy declaration and implementation. Millions of Africans are liable to continue to be displaced as a result of conflict and disasters.

In order to achieve the optimistic trajectory of facilitating mobility and addressing irregular and forced migration, African countries should step up efforts in two directions. First, fast-tracking the adoption, ratification and implementation of African free movement regimes (AU and RECs’ free movement protocols); the AfCFTA can be a game-changer in facilitating the massive potential of Africa and Africans to enjoy the full benefits of mobility. A free mobility regime requires better-resourced airports, and border posts capable of differentiating bad from good mobility.

Second, African countries of origin need to improve the human security of their population to narrow the gap between aspired living standards in destination countries and actual living standards in origin countries. Those with decent living standards are less likely to take risky, dangerous irregular migration routes and will tend to primarily seek legal pathways. Legal mobility channels within Africa and between Africa and other regions may help reduce irregular migration.

To facilitate legal pathways to mobility, the AU and EU need to reset their current partnership on migration and mobility to avoid the arguably self-defeating EU-driven impulse to put all their migratory eggs in one basket: return, readmission and reintegration. Furthermore, the EU should respond to the longstanding demands of Africans for greater access to legal mobility, less cumbersome visa regimes, and the protection of migrants’ rights regardless of immigration status.

References

1. Parshotam, A., ‘A brief guide to the Continental Free Trade Agreement’, 2017 (https://www.africaportal.org/features/brief-guide-continental- free-trade-agreement/).

2. Ibid.

3. International Organization for Migration, World Migration Report 2022, 2021, p. 23 (https://publications.iom.int/books/world-migration- report-2022).

4. Statista, ‘Number of emigrants from Africa from 2000 to 2020’, 2021 (https://www.statista.com/statistics/1231600/number-of-emigrants- from-africa/).

5. World Migration Report 2022, op.cit., pp. 60-63; Flahaux, M-L. and De Haas, H., ‘African migration: trends, patterns, drivers’, Comparative Migration Studies Vol. 4, No 1, 2016 (https://comparativemigrationstudies. springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40878-015-0015-6).

6. Maru, M. T., ‘Migration policy-making in Africa: determinants and implications for cooperation with Europe’, Migration Policy Centre, European University Institute, 2021 (https://cadmus.eui.eu/ handle/1814/71355).

7. African Development Bank, Africa Visa Openness Report 2016, 2016 (https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Generic-Documents/Africa_Visa_Openness_Report_2016.pdf).

8. United Nations High Commission for Refugees, UNHCR Global Trends 2010, 2010 (https://www.unhcr.org/4dfa11499.pdf).

9. United Nations High Commission for Refugees, ‘Refugee Data Finder’ (https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/#:~:text=Data%20on%20).

10. United Nations High Commission for Refugees, ‘Africa Regional Summary’, 2018 (https://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/gr2018/ pdf/03_Africa.pdf).

11. Christophersen, E., ‘These 10 countries receive the most refugees’, Norwegian Refugee Council, 2020 (https://www.nrc.no/perspectives/2020/the-10-countries-that-receive-the-most-refugees/).

12. ‘56 800 migrants dead and missing. “They are human beings.”’, AP News, 2 November 2018 (https://apnews.com/article/immigration- north-america-ap-top-news-south-africa-international-news-e509e15 f8b074b1d984f97502eab6a25).

13. Geddes, A. and Maru, M.T., ‘Localising migration diplomacy in Africa?: Ethiopia in its regional and international setting’, Migration Policy Centre, European University Institute, 2020 (https://cadmus.eui.eu/ handle/1814/68384).

14. ‘Africa’s rising cities: How Africa will become the center of the world’s urban future’, Washington Post, 19 November 2021 (https://www. washingtonpost.com/world/interactive/2021/africa-cities/).

15. Statista, ‘Urbanization rate in Africa 2000-2025’, 2021 (https://www. statista.com/statistics/1226106/urbanization-rate-in-africa/).

16. David, R., ‘Megacities of Africa’, Infoplease, 2021 (https://www.infoplease.com/world/geography/megacities-of-africa#:%7E:text=Luanda%2C%20Angola%E2%80%99s%20capital%20city%20).

17. Mitchell, J., ‘African e-Connectivity Index 2021: The final frontier and a huge opportunity’, Investment Monitor, 2021 (investmentmonitor.ai/tech/ africa-connectivity-index-2021)

18. Statista, ‘Internet penetration rate in Africa as of December 2021, compared to the global average’, 2022 (https://www.statista.com/ statistics/1176654/internet-penetration-rate-africa-compared-to- global-average/).

19. ‘African e-Connectivity Index 2021: The final frontier and a huge opportunity’, op.cit.

20. World Bank, ‘Achieving broadband access for all in Africa comes with a $100 billion price tag’, 2019 (https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/ press-release/2019/10/17/achieving-broadband-access-for-all-in- africa-comes-with-a-100-billion-price-tag).

21. Eckstein, D., Künzel, V. and Schäfer, L., ‘Global Climate Risk Index 2021’, Germanwatch, 2021 (https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/ resources/Global%20Climate%20Risk%20Index%202021_1_0.pdf).