You are here

Table of contents

The EU as a maritime security provider

Introduction

Maritime security is one of the fundamental strategic interests of the European Union. Then HR/VP Federica Mogherini reiterated this fact at the conclusion of the informal meeting of EU defence ministers in Helsinki at the end of August 2019, adding that there was a ‘growing demand for an EU role as a maritime security provider not only in our region, but also further away’ – especially in Asia and the Indian Ocean. As a global trading power, the EU is vitally dependent on free, open and safe maritime shipping: 90% of its external and 40% of its internal trade is seaborne. The value of goods transported by sea is 1.8 times higher than that of goods transported by air and almost three times higher than that of goods transported overland.1 In 2018 alone, the value of trade between the EU and Asia, home to its main economic partners, reached €1.4 trillion, with 50% of it transiting through the Indian Ocean.

As a result, the EU has a vested interest in a secure maritime domain and it is only natural that it should contribute to its preservation, especially in waters connecting it to its main economic partners in Asia. It is also natural that Asian countries want to see Europe becoming more proactively involved in addressing the many maritime security challenges – both traditional and non-traditional – in the Indo-Pacific, especially given its aspiration to play a greater security role in the region.

The question is: can the EU perform such a role? How realistic is its ambition to become a maritime security provider in the region and how might it go about accomplishing this? The purpose of this Brief is to look into why, where and how Europe could contribute to improving the maritime security environment in the Indo-Pacific. A closer look at the current situation and the multitude of maritime security challenges facing littoral states in the region reveals several niches that the EU could fill. Analysing the Union’s key attributes and achievements in the maritime security field, the Brief identifies features and capacities that can effectively add value to regional security and stability. Three main aspects stand out in this regard.

First, the EU’s low-key security profile can work to its advantage. As much as not having a strong army can be seen as a major disadvantage in promoting one’s security interests, when it comes to promoting multilateral cooperation or addressing functional issues, it can be a diplomatic asset. Against the backdrop of mounting strategic rivalry between the US and China and the deleterious effect that this is having on the regional security environment, Europe appears as an approachable and reliable partner to all parties regardless of their strategic orientation, and a neutral security provider.

Second, the EU possesses the technical capacity to address functional maritime security issues. Through its own experience, Europe has developed unique operational expertise, institutional capacities and human resources to manage complex maritime challenges in a multilateral, multi-stakeholder environment. Whether in enhancing Maritime Domain Awareness, cooperation and coordination between navies, law enforcement agencies and non-state actors, or promoting a comprehensive approach to maritime crisis management (visible in its efforts to fight against piracy off the coast of Somalia), the EU has acquired a panoply of skills that may prove valuable in addressing Asia’s many everyday maritime security concerns, from tackling seaborne crime to disaster response.

Third, the EU’s reputation as a normative power is an asset that stands it in good stead. Respect for and promotion of the rule of law is a priority for the EU, including international agreements and conventions such as the UN Convention on the Law of the Seas (UNCLOS), the very foundation of the global rules-based maritime order. The Union’s leadership in promoting international ocean governance under the framework of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), effective since 2016, positions it as an ideal partner for addressing the growing security concerns related to the negative effects of climate change, unsustainable resource exploitation and environmental destruction, as well as for fostering the development of sustainable ‘blue economies’ – a goal for many Asian countries.

From a foreign policy perspective, maritime security extends the geographical scope of the EU’s strategic interests and constitutes a key arena for deepening political and security cooperation with partners. More than ever, there is a strategic opportunity for the EU to capitalise on its know-how to promote its foreign policy objectives in the Indian Ocean and beyond. If Europe pursues its intention to become a maritime security provider and formulates a pragmatic and realistic approach along these lines, it could have the effect of significantly boosting the EU’s global security footprint.

Maritime security in the Indo-Pacific: current challenges

The mounting strategic rivalry between China and the US is a major underlying driver of increased instability in the region. As Beijing expands its blue water capabilities to secure its interests along its commercial sea routes into the Indian Ocean, the US, together with other likeminded countries (notably India, Japan and Australia), is stepping up efforts to preserve the status quo, resulting in the growing militarisation of the regional waters. This new strategic dynamic means that many small and middle-sized countries in South and Southeast Asia feel pressured to pick sides. Furthermore, this increasingly polarised environment weakens existing regional multilateral structures such as the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) or the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) which provide inclusive cooperative frameworks for dealing with everyday maritime security concerns.

A number of geopolitical hotspots in the region pose a direct threat to the safety and freedom of international shipping. Current tensions between Washington and Tehran in the Persian Gulf constitute just one example. Iran’s seizure of the British-flagged tanker Stena Impero in June this year, attacks on Norwegian and Japanese-owned oil tankers and the increased multinational naval presence in the regional waters have a serious impact on the safety and cost of transit through the Strait of Hormuz, a strategic chokepoint carrying a third of global oil shipments (21 million barrels per day in 2018). Despite the deployment of a US-led maritime coalition to control the situation, insurance costs for shipping companies with vessels plying through the Strait have increased tenfold since the beginning of the crisis in June 2019.2

Farther from home, China’s increasingly imperious assertion of its territorial claims and build-up of artificial islands in the disputed South China Sea, which carries one third of overall global shipping (representing trade worth an estimated $5.3 trillion in 2018) is an ongoing source of concern for the international community and maritime user-states. The US and other nations (including France and the UK) have stepped up their naval presence to protest against Beijing’s actions and promote freedom of navigation, resulting in the increasing militarisation of the regional waterways, with the potential to escalate into a more dangerous conflict – especially given the current state of US-China tensions.

But conventional security threats are not the only problem in the maritime Indo-Pacific. Strategic rivalries tend to divert the attention of policymakers from the many non-traditional security challenges which continue to proliferate in the meantime. Piracy – whether in the Gulf of Aden or in the Straits of Malacca – has been the one issue seriously addressed by the international community, precisely because of its economic impact on global shipping. However, other seaborne criminal activities, including Illegal unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing, or drug, weapons and people trafficking, continue to undermine local economies and regional stability.

Finally, the region is particularly sensitive to marine environmental challenges, related to the unsustainable exploitation of natural resources, destruction of natural marine habitats and the negative effects of climate change, which entail severe long-term security repercussions, from seafood scarcity to mass migration. Experts warn that low-lying coral atolls in the Indian and the Pacific Ocean (such as the Marshall Islands, the Maldives and the Seychelles) are not only progressively sinking due to rising sea levels; they will be without freshwater resources and therefore uninhabitable already by the middle of this century.3 Extreme weather events are likely to become commonplace, accentuating the need for cooperation in disaster preparedness and response. Yet, although environmental issues are critical concerns that can only be addressed through concerted efforts by all regional actors, they usually occupy the lowest level of strategic priorities, and are costly and institutionally demanding to address.

No navy, no leverage?

When it comes to involvement in conventional maritime security hotspots, the EU’s leverage remains limited. If all the naval assets of individual member states could be combined, Europe would indeed possess one of the world’s largest navies. A number of initiatives have been put forward since 2016 to boost interoperability and readiness in the naval sector, as part of the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) framework.

The two maritime CSDP missions deployed by the EU so far – the counterpiracy Operation Atalanta in the Gulf of Aden and the Mediterranean search and rescue Operation Sophia – have been efficient in addressing the tasks for which they were designed. However, they can hardly be considered convincing examples of the EU’s prowess as a global maritime security provider in a traditional sense: Operation Sophia cannot use any naval assets due to the opposition of the Italian government and Operation Atalanta currently operates only two frigates.

Piracy – whether in the Gulf of Aden or in the Straits of Malacca – has been the one issue seriously addressed by the international community, precisely because of its economic impact on global shipping.

The newly proposed concept of ‘coordinated maritime presences’, enabling ad hoc voluntary information, awareness, and analysis sharing among member states’ navies in areas of common strategic interest, is a significant development. Building on the established naval presence of any member state around the world, it could substantially boost the Union’s maritime capacity and outreach globally. Although the concept is still in its early stages and would be politically difficult to apply in such strategically sensitive areas as the Strait of Hormuz or the South China Sea for now, it could increase the EU’s visibility as a maritime security provider in the long term. As EU defence ministers agreed in Helsinki, the mechanism will be first tested in the Gulf of Guinea.

So how can the EU contribute to ease the impact of geopolitical crisis on maritime security? One possibility is to rely on its member states. Aware of the Union’s operational limitations, the EU Maritime Security Strategy explicitly encourages member states to use their military forces to defend freedom of navigation and fight illicit activities worldwide.4 The South China Sea presents a good example. The navies of two EU member states with blue water capabilities, France and the UK, are currently deployed in the regional waters to defend freedom of navigation. Although both navies operate in their national capacities, their actions effectively protect the interests of all European countries. France has been especially vocal about the European dimension of its mission and regularly welcomes officers of other EU member states on board its ships.

Second, the EU can apply diplomatic pressure, promote legal solutions and conflict-prevention mechanisms and support capacity building of involved parties in these domains. In the case of the South China Sea, the EU conducts regular dialogues with Vietnam, ASEAN, and recently China, to discuss concrete provisional solutions that could defuse tensions, such as joint resource development, environmental cooperation and conflict-prevention measures. Although the EU’s profile as a normative actor has been partly undermined by the weak official statement issued in the aftermath of the ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in the case of Philippines vs. China in June 2016, the HR/VP and other high-level officials have been vocal in their condemnation of China’s assertive claims and militarisation of the regional waters.

The final option is indeed some form of naval involvement. The prospect of the EU deploying a mission or operation within its CSDP framework in the context of the two crises mentioned above is highly unlikely, if not impossible. First, although they impact on maritime security, they are first and foremost geopolitical crises and a deployment would require consensus among all member states. Second, while important, they do not pose an existential threat to the EU’s security.

However, the proposed Coordinated Maritime Presence concept, once finalised, could provide potential avenues. Whether in tracking illicit activities or protecting commercial shipping, its aim is to increase awareness and share information, also in coordination with other actors present and coastal countries sharing the same concerns. This could potentially be valuable in the Strait of Hormuz, for instance.

Regardless of the evolution of the geopolitical crisis itself, the Strait is likely to become very busy. The US-led maritime coalition currently includes the UK, Australia, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia. Besides the immediately involved parties, those most concerned with the safety and stability of the strategic chokepoint are Asian countries. As of 2018, 76% of oil shipments through the Strait of Hormuz were destined for China, India, Japan and the Republic of Korea (ROK), all of which already have naval assets in the Gulf of Aden since 2009 and might consider sending their own patrols to protect their ships.

The high concentration of international naval forces, together with already heavy commercial traffic, in a narrow shipping waterway means that there is an increased risk of miscalculations and incidents that might escalate into military conflict in the Strait of Hormuz. The need for coordination is therefore more acute than ever. Since the beginning of the crisis in June this year, there has been a consensus on the need to provide some kind of European response. Options to deploy an observer mission and/or a protective mission have been on the table. But one substantial role that the EU could play, and which could contribute to regional stability, would be to coordinate the naval presences already in place – a role it successfully played during the piracy crisis in the Gulf of Aden.

Atalanta: showcasing the EU’s naval diplomacy

Europe’s contribution to the fight against piracy in the Gulf of Aden is the most visible example of its potential as a maritime security provider. The EUNAVFOR Operation Atalanta deployed in early December 2008, joining the forces of NATO, India and Russia, and was followed by China, the multi-naval Combined Maritime Task Force (CMF 151), Japan and Korea shortly after in 2009. The merits of the mission in countering piracy, together with the EU’s civilian missions EUCAP Nestor and EUTM Somalia, have been widely acknowledged. However, its role in facilitating communication and coordination of the international naval presence is equally important, and its value in promoting the image of the EU as a potential security actor cannot be underestimated.

Thanks to its institutional resources and capacity, EUNAVFOR soon took the lead in coordinating cooperation among all actors present in the area – whether military or civilian – sharing the same goal. First, through the establishment of the Maritime Security Centre of the Horn of Africa (MSCHOA) and its real-time information-sharing platform MERCURY – accessible to both civilian and military maritime stakeholders present in the region. Second, through its prominent role in the Shared Awareness and De-confliction (SHADE) mechanism. Originally put in place in 2008 to coordinate escorts of commercial shipping through the Internationally Recommended Transit Corridor (IRTC), the Bahrain-based initiative eventually became a useful platform also for coordinating naval activities and discussing overall maritime security issues in the region.

Atalanta also served as a useful diplomatic tool in building ties with third parties, notably East Asian countries, most of which had never interacted with any EU military mission before. The innovative, multinational character of the operation naturally attracted the interest of other navies in place. Moreover, the EU’s low-key security profile made it a more acceptable interlocutor for countries that would be otherwise reluctant to cooperate with other, more traditional, strategic players.

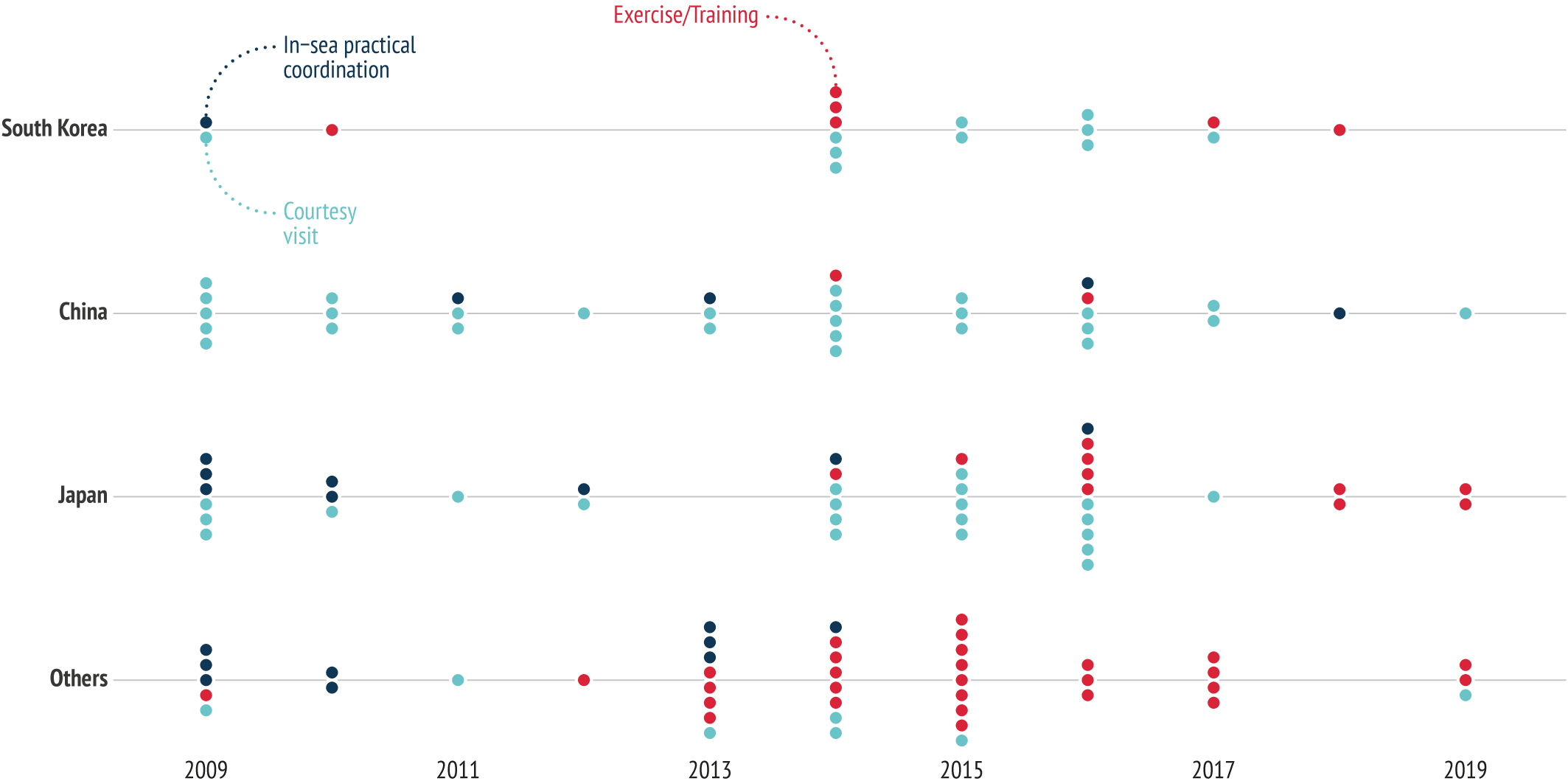

ATALANTA’s diplomacy

Interactions with third parties

Data: EU NAVFOR Atalanta, 2019

This was the case with China. The Chinese Navy Escort Taskforce (CNET), deployed to the Horn of Africa in Beijing’s first long-distance, blue water naval operation. Operating independently from the allied CTF 151 counter-piracy operations and mostly protecting Chinese commercial vessels only, it engaged in ad hoc interactions with other navies, limited to ship and port visits, as well as very occasional joint exercises with foreign navies. Cooperation with European forces has been most advanced, culminating in a combined medical evacuation exercise in October 2018. Prior to the exercise, the EUNAVFOR Operational Commander was invited to the Chinese naval base in Djibouti on 8 August 2018, marking the first and only time Western military personnel visited the Chinese overseas base.

Successful operational cooperation within the counter-piracy framework was in many cases instrumental in building up closer formal political and security ties. Cooperation with South Korea stands out in this respect. The ROK Navy first interacted with EUNAVFOR in the context of its deployment alongside the Combined Task Force (CTF) in August 2009. The positive experience that ensued eventually led to the signature of the EU–ROK Framework Participation Agreement (FPA), a legal framework allowing third parties to take part in the EU’s crisis-prevention efforts. The accession to the FPA made Seoul the first Asian partner to institutionalise security cooperation with the EU.

Finally, in October 2017, EUNAVFOR’s Dutch Navy warship HNLMS Rotterdam hosted a group of Indonesian naval officers, followed by a visit to Atalanta’s Operational Headquarters and the Maritime Security Centre for the Horn of Africa (MSCHOA) in Northwood (UK). Indonesia was the first country to voice interest not only in the military aspects of the operation, but also in the practical experience of cooperating with civilian agencies in the field and the overall comprehensive approach. Several exchanges have taken place since then, sharing best practices in civil-military cooperation with Indonesia, but also other Southeast Asian nations.

Until today, Operation Atalanta remains the point of reference for Asian countries when discussing the EU’s contribution to maritime security. It demonstrated the EU’s comprehensive approach to crisis management, effective operational capacity, as well as the technical resources it can offer. The emphasis on maritime multilateralism, interstate and inter-agency cooperation, as well as the EU’s willingness to share its capacities have been especially appreciated.

Maritime Domain Awareness: sharing is caring

Clearly, multilateral cooperation and coordination is key to effective management of everyday maritime security issues, but also an essential prerequisite for assessing the situation at sea, referred to as Maritime Domain (or Situational) Awareness (MDA/MSA).

Building an effective, real-time and shared understanding of the maritime domain has been one of the EU’s greatest operational achievements. MDA involves surveillance, intelligence and information collection about ships through human reports and automated systems such as Automatic Identification Systems (AIS), Long-Range Identification and Tracking (LRIT), radars and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), and subsequent fusion and sharing of this data among all relevant stakeholders. It is an essential tool in maritime security used for law enforcement and incident management – whether in countering piracy, monitoring illicit traffic and other malign activities, rescuing ships or containing oil spills.

Used in different sectors of activities, such as defence, customs and border control, shipping safety and environmental protection, it is applied by different authorities at the national level, which often makes coordination institutionally and legally complex. Transnational and multilateral by nature, MDA also requires effective international cooperation.

Building an effective, real-time and shared understanding of the maritime domain has been one of the EU’s greatest operational achievements.

The EU has become a champion in fostering MDA at home, committed to build a Common Information Sharing Environment (CISE) system, which should integrate all member states’ agencies as well as relevant EU institutions by 2020. However, integrated maritime surveillance and information sharing systems already exist to address various functional areas such as monitoring oil spills, illegal activities and human trafficking, provided by the Integrated Maritime Services platform of the European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA). The Maritime Surveillance (MARSUR) Exchange system, developed by the European Defence Agency, facilitates MDA in military activities and is used to support the EU’s CSDP operations (such as the EUNAVFOR Operation Sophia) among others. Finally, the online information-sharing platform MERCURY, hosted by MSCHOA, is a concrete example of the usefulness of MDA not only to coordinate and improve counter-piracy activities, but also to facilitate international cooperation. An open, web-based tool, it has been used by all stakeholders in the region, both civilian and military, including from countries like Russia and China.

Enhancing MDA globally has been one of the EU’s main capacity-building activities and contributions to maritime security. The EU is currently engaged in active projects across the countries of the Gulf of Guinea (CRIMGO) and the wider Indian Ocean (CRIMARIO) building MDA capacity through training courses, operational tools and facilities. The latest such tool has been the platform for information sharing and incident management IORIS, set up in 2018 to facilitate communication and coordination of operations in the Indian Ocean area. Owned by the Indian Ocean Commission (IOC), it has been widely appreciated among regional actors and was chosen as the communication tool during the last ‘Cutlass Express’ naval exercise in 2019.5 The Union’s Programme to Promote Regional Maritime Security (MASE) provides funding to the Regional Maritime Information Fusion Centre in Madagascar and the Regional Centre for Operational Coordination in the Seychelles.

Avenues for further capacity building and promotion of cooperation in MDA abound. Thanks to its past record, the EU is already a partner of choice for African countries requiring assistance in the process of ratification and implementation of the African Charter on Maritime Security (Lomé Charter). Southeast Asian countries have also shown interest in European experience in the realm of MDA, discussed regularly through the annual EU- ASEAN High-Level Dialogues on Maritime Security Cooperation, as well as other channels. In sum, effective MDA is not only necessary to ensure safety and security at sea; it has a real potential to enhance trust, confidence and multilateral cooperation in the Indo-Pacific.

Connecting the Indo-Pacific

One of the key objectives of the various proposed Indo-Pacific outlooks, whether Japan’s ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ concept, the US strategy for the Indo-Pacific, or the ‘ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific’, is to build a more connected regional architecture to boost trade and growth across the Indian Ocean.

Connectivity has also become the new buzzword in EU-Asia relations. The promotion of efficient, sustainable and rules-based connectivity has been the EU’s policy to boost strategic ties with Asia, as noted in its ‘Joint Communication on connecting Europe and Asia’, known as the ‘connectivity strategy’, released in September 2018. When it comes to the maritime sector however, the strategy only refers to clean and sustainable shipping and port effectiveness, omitting the crucial importance of maritime security cooperation as a prerequisite for sustaining connectivity at sea.

Connectivity has several implications for regional maritime security. First of all, the proliferation of connectivity initiatives mirrors and intensifies existing strategic rivalries. The development of transport infrastructure has been a key rationale behind China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), driving its expansion into the Indian Ocean, Africa and Europe. Enhancing connectivity has subsequently become the focus of other regional players, including Japan, India, ASEAN and the US, wary about China’s expanding influence across the region. Paradoxically therefore, while connectivity aims to boost trade and interstate cooperation, it also contributes to the growing polarisation and sense of insecurity in the region.

Second, there is a fine line between boosting connectivity and the growing militarisation of the region. On several occasions, China has used the civilian port facilities it has built in Sri Lanka and Pakistan to dock its naval ships. The inauguration of the Chinese navy’s first overseas base in Djibouti in August 2017, to provide logistical support for its ships escorting commercial shipping, is another example of the interconnectedness between trade and military presence. Beijing’s announcement of its intention to build similar logistical bases in the 2019 Defence White Paper asserts the shift in its global security outlook.

While building ports is indeed necessary to boost trade, this cannot flourish in an environment rife with crime and illicit seaborne trafficking. The proliferation of criminal networks along the East African coast has been weakening local economies by discouraging investment and tourism and preventing the development of normal fisheries activities. East Africa has become known as the ‘Heroin Coast’, with up to 40 tonnes of the drug smuggled through the region every year (a number that has increased as a result of intensified law enforcement along the traditional Balkan route in the context of the migration crisis) due to ineffective border controls.6 The region is a major hub for wildlife trafficking, which, fuelled by the increasing demand from Asia, has become one of the world’s most lucrative organised crimes.7 Finally, the illegal charcoal trade from Somalia to the UAE and Oman is another major source of instability in the region, generating revenue for the local terrorist group al-Shabaab.8

...while connectivity aims to boost trade and interstate cooperation, it also contributes to the growing polarisation and sense of insecurity in the region.

Effective maritime law enforcement is therefore a key prerequisite for enhancing stability and connectivity in the region and this is a niche area for which the EU is well-suited. Bolstering the capacity of local military forces and coastal patrols, as well as investing in building a viable blue economy to ensure the long-term, sustainable development of the region has been the basis of the EU’s comprehensive approach in the Horn of Africa. Enhancing MDA in the wider Indian Ocean region has been the goal of the EU’s project CRIMARIO. This programme, which has been providing capacity-building and training courses to regional law enforcement agencies since 2015 (and lately set up its web-based IORIS system, described in the previous section), has been another substantial value-added for regional law enforcement capacity. Europe has also been actively involved in countering IUU fishing, developing sustainable fisheries and building blue economies in East Africa and the Indian Ocean (bilaterally and through the Indian Ocean Commission), crucial for sustainable growth and stability in the region.9

Overall, the EU’s record in maritime capacity-building in the Indian Ocean region, support of existing cooperative structures and promotion of good ocean governance are valuable assets for enhancing connectivity in the Indo-Pacific and for working with foreign partners sharing the same goal. The newly established “EU-Japan Partnership on Sustainable Connectivity”, signed on the occasion of Japanese Prime Minister Abe’s visit to Brussels at the end of September, focuses mostly on building quality infrastructure and improving business conditions to encourage investment in the region. But maritime connectivity cannot be achieved through physical infrastructure alone. Shipping needs safe and stable seas, which can only be sustained through effective governance.

Ocean governance: a new paradigm in maritime security

The EU’s ambition to become a maritime security provider should not be viewed solely through the prism of conventional security. Europe does not have a navy that could be deployed to police international waters. On the other hand, the Indo-Pacific maritime security environment does not need more warships; it needs more cooperation and common sense.

The maritime domain is a global common, requiring specific forms of management. The transnational character of maritime security challenges shifts the focus from unilateralism to multilateral cooperation, from territorial defence to functional security, and from military action to broader constabulary activities and responsible ocean governance. In sum, the maritime realm in today’s globalised world is an inherently post-modern security environment, where the interests of nation-states intertwine, and which cannot be secured by the traditional roles of navies alone.

‘Navies reflect the nature of societies in which they operate’, noted the renowned naval historian Geoffrey Till.10 The same can be said about a country’s overall approach to maritime security. As a post-modern geopolitical construct, Europe has developed a unique set of skills to manage its maritime security challenges at a regional, multi-stakeholder level. The 2014 EU Maritime Security Strategy (EUMSS) represents the most comprehensive policy framework for regional maritime governance, whose holistic approach (including civilian-military collaboration, public-private cooperation and ecosystem-based management) can serve as an inspiration to other regions, such as the Southeast Asian sub-region covered by ASEAN, which aspire to greater maritime security integration.

Moreover, since 2016, the EU has taken a leading role in promoting international ocean governance. In line with the UN 2030 Sustainable Development Goal 14, it has implemented over fifty projects for the sustainable use and conservation of marine resources, development of blue growth, adaptation to climate change and support of scientific research. So far, it has committed €560 million to working with third parties and over €500 million to marine research and innovation.11 Given the high stakes for the marine environment and the acute need for good ocean governance in the Indo-Pacific, the EU is and will continue to be an indispensable partner in the years to come.

Conclusion

At a time when the EU is seeking to boost its security profile in the region, the maritime domain naturally constitutes an area of common interest. The EU currently engages in regular High-Level Dialogues on Maritime Security with ASEAN (since 2013), India (since 2017) and recently held its first meeting with China (October 2019). Maritime security is also one of the pillars of Brussels’ initiative to promote ‘security cooperation in and with Asia’, together with cybersecurity and crisis management, with the aim of boosting strategic relationships with India, Indonesia, Japan, the ROK and Vietnam. Finally, until 2021 the EU co-chairs the ASEAN Regional Forum Inter-Sessional Meeting on Maritime Security (2018-2021), in which it tries to promote cooperation on non-traditional maritime security issues, including port security, IUU fishing and law enforcement.

Becoming a maritime security provider, however, requires a more proactive involvement also in practical initiatives and cooperation outside the conference walls. The EU’s potential as a diplomatic mediator and added value in facilitating communication and cooperation at sea, as demonstrated in its counter-piracy deployment in the Gulf of Aden, could be used in other similar situations involving a build-up of international naval forces, such as the Strait of Hormuz. Its capacity to build and sustain multilateral cooperative frameworks for enhanced Maritime Domain Awareness, countering illicit activities or addressing environmental challenges can be most useful in enhancing maritime security and connectivity across the Indian Ocean region. Finally, its commitment to promoting a rules-based international maritime order and sustainable ocean governance will be vitally important in light of growing geopolitical competition in the region.

Overall, Europe’s institutional and operational expertise in multi-stakeholder maritime governance represents a valuable asset to build on. Promoting this expertise within its foreign and security initiatives, including connectivity partnerships with Asian countries, would make most sense. Whether or not the EU will succeed as a maritime security provider in the Indo-Pacific depends on the type of actions it is expected to perform. If it is to steer cooperation, build technical and institutional capacities and defend the rule of law, then it has the potential to make a positive and concrete contribution to maintaining security and stability in the region.

References

* The views expressed in this Brief are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the EUISS or of the European Union.

1) Eurostat, Globalisation Patterns in EU Trade and Investment, 2017, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/8533590/KS-06-17-380-EN-N.pdf/8b3e000a-6d53-4089-aea3-4e33bdc0055c

2) “Shipping insurance cost to remain high in the Persian Gulf”, Ship Technology, September 3, 2019, https://www.ship-technology.com/comment/shipping-insurance-costs-to-remain-elevated-in-the-persian-gulf/

3) Curt Storlazzi et al., “Most atolls will be uninhabitable by the mid-21st century because of sea-level rise exacerbating wave-driven flooding”, Science Advance, vol. 4, no. 4 (April 2018), https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/4/4/eaap9741.

4) EU Maritime Security Strategy, 2014, p.10, https://ec.europa.eu/maritimeaffairs/policy/maritime-security_en.

5) EU CRIMARIO, “IORIS Successfully Used During Cutlass Express Exercise”, March 2019, https://www.crimario.eu/en/2019/03/10/ioris-successfully-used-during-cutlass-express-exercise/

6) UNODC, “Drug Trafficking Patterns to and from East Africa”, 2019, https://www.unodc.org/easternafrica/en/illicit-drugs/drug-trafficking-patterns.html.

7) UNODC, “Transnational Organised Crime in Eastern Africa: A Threat Assessment”, 2013, https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/Studies/TOC_East_Africa_2013.pdf.

8) According to the Monitoring Group UN report, illegal charcoal tax generates a revenue of $7.5million per year. United Nations Security Council (UNSC), “Letter dated 7 November 2018 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 751 (1992) and 1907 (2009) concerning Somalia and Eritrea addressed to the President of the Security Council”, November 9, 2018, https://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3.sourceafrica.net/documents/118531/Report-of-the-Monitoring-Group-on-Somalia-and.pdf.

9) In 2018, the EU provided €28 million for promoting sustainable fisheries in the region under the E€OFISH Programme.

10) Geoffrey Till, “Globalization: Implications of and for Modern/ Post-modern Navies of the Asia-Pacific”, RSIS Working Paper no. 140, S. Rajaratnam School of international Studies, October 2007, https://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/rsis-pubs/WP140.pdf.

11) Joint Report to the European Parliament and the Council, “Improving international ocean governance – two years progress”, EU Monitor, March 15, 2019, https://www.eumonitor.eu/9353000/1/j4nvhdfdk3hydzq_j9vvik7m1c3gyxp/vkwtjboi1et9#footnote3.