You are here

The EU and Latin America

Introduction

As the EU grapples with a new multipolar world order in which multilateralism, economic stability and democracy are in retreat, potential partners such as Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) (1) assume greater importance. Long overlooked by the EU, this is a region that shares many similar challenges, values and priorities, not least in accelerating its digital and green transitions in a socially inclusive manner. The EU could find an invaluable ally in LAC to cooperate with at the regional, subregional, and bilateral levels not only on both transitions but more broadly in sustaining the rules-based multilateral order.

Yet the EU should not expect a seamless return to the region. Other actors such as China and Russia have stepped into the void during years of EU neglect and indifference, some with the resources and strategic vision that the EU has lacked, while the region itself has developed its own sovereign agenda. For the EU to be considered a valuable partner, it must make a competitive political, economic and social offer to the region. This Brief examines the common challenges faced by the EU and LAC, the specific needs of each region, and how the two can cooperate in today’s contested international environment.

Common global challenges

Latin America and the EU face three common challenges.

First, the ongoing weakening of the multilateral system and its institutions. As became evident during the Covid-19 pandemic, the multilateral system faces enormous challenges in providing global public goods, even those as essential and undisputed as healthcare. It has also failed to prevent the proliferation of unilateral sanctions, resolve trade disputes or uphold security and basic principles of international law such as territorial integrity, as seen in the war in Ukraine (2).

Second, the fragmentation of globalisation and rise of economic protectionism. The post-Covid economic recovery has been largely oriented towards bolstering security, both economic and military, to limit or reduce interdependence through practices such as near-shoring or ‘friend-shoring’ (3). In the EU, this agenda is dubbed ‘strategic autonomy’ or ‘European sovereignty’. In China, Beijing calls for a ‘dual circulation’ model and economic decoupling from the West. In the United States, the ‘Build Back Better’ programme comes together with a ‘Buy American’ policy and an Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) involving the use of massive economic subsidies to incentivise local investment to speed up its green transition. Finally, in Latin America, a reindustrialisation programme based on green and digital growth, including establishing production hubs inside the territory, is sought to generate new welfare opportunities. However, this agenda of fragmentation and politically-driven foreign direct investment risks reducing diversification and increasing vulnerabilities to macroeconomic shocks.

Latin America, with its immense natural resources, is unmistakably an attractive partner for the EU.

Meanwhile, tensions between the United States and China continue to spill over into markets, particularly in the technology domain, in the form of sanctions and export controls, generating further uncertainty about the future of the global economy. At the same time, global supply chains are compromised, bottlenecks in transportation and production remain in place, e.g., in semiconductors and critical raw materials, and compliance with trade agreements or norms is uncertain.

The third shared challenge stems from the fragility of domestic political processes. The world has experienced a significant democratic regression over the past 17 years, affecting both the quantity and quality of existing or aspiring liberal democracies (4). Political instability, electoral volatility, weak political institutions, and media, as well as growing distrust in the state, are now the norm and LAC and the EU are by no means exempt from this trend (5). Weakened democracies translate to a deteriorated rules-based multilateral order in which cooperation between regions and within regions is much harder.

The EU: Needs and possibilities

The war in Ukraine has prompted the EU to engage in a process of strategic transformation and to further strengthen its strategic autonomy (6). Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s declaration that the world faces a Zeitenwende or historic turning point calls for renewed focus on all regions of the world to assess how each might enhance the EU’s strategic autonomy, defined as ‘the capacity of the EU to act autonomously – that is, without being dependent on other countries – in strategically important policy areas’ (7), and sustain a rules-based multilateral order (8).

Both the (intimately linked) green and digital transitions are essential for advancing the EU’s strategic autonomy. Yet geopolitical tensions are complicating both. The war in Ukraine has not only delayed the energy transition but also made it more costly, as well as more urgent (9). As it moves to free itself from the costly dependencies associated with the fossil-fuel economy – not least those on Russian gas – the EU must ensure its green and digital transition does not result in increased dependence on China and the United States. However, the EU lacks the critical technologies to complete its energy transition, including for batteries, hydrogen and wind turbines (10). Critical technologies for the digital transition from semiconductors to submarine cables are similarly lacking (11). Finally, Europe also lacks the critical materials needed for both transitions, and is dependent on supplies from a handful of countries, in particular China, which supplies 98 % of its rare earths and 66 % of its critical raw materials (12).

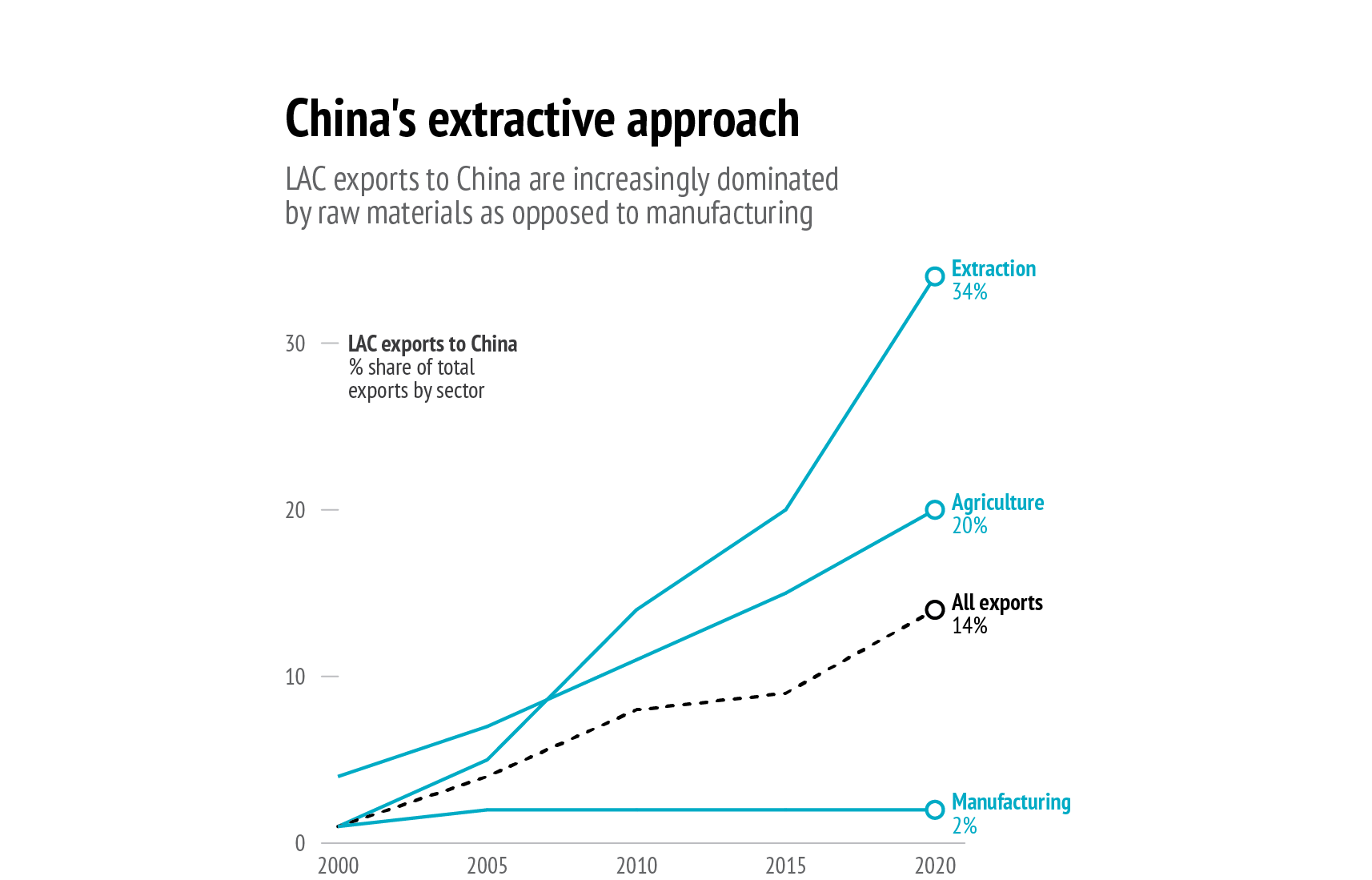

This not only obliges the EU to advance with its green and digital industrialisation agenda but to seek new partners: Latin America, with its immense natural resources, is unmistakably an attractive one. The region is already an established producer of several minerals critical for clean energy technologies and has the capacity to expand production in various areas (13). This has not gone unnoticed by actors such as Chinese companies who, as the graph below indicates, have significantly ramped up their investments in the extraction and processing of critical minerals in LAC over the past two decades, particularly in lithium and nickel (14).

NB: China includes Hong Kong and Macao.

Data: UN Comtrade, 2023; Based on Margaret Myers, ‘China y América Latina, “terra ignota”’, Política Exterior, November 2022

There is no doubt that the EU is late to the LAC region (15). Immersed in its own economic crisis, compounded by Covid-19, and distracted by other urgent challenges (16), the EU has paid uneven and intermittent attention to the region, particularly in the last decade. The EU’s 2021-2027 budget reduced funding for Latin America and the Caribbean by 14 %, as the bloc shifted its attention towards Africa and the Middle East (17). The promise of a strategic partnership formulated at the Rio 1999 summit (18) has not only failed to materialise but has been completely overshadowed by China’s burgeoning commercial and investment presence (19), Russia’s albeit smaller footprint (though important in political aspects) and, of course, that of the United States.

Indeed, while the value of the region’s trade with the EU grew from €185.5 billion in 2008 to €225.4 billion in 2018, that with China increased tenfold in the same period. 21 countries in the region are now members of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, while the EU’s trade negotiations with Mercosur remain stalled. Beijing estimates that, by 2025, the value of Chinese trade and investment with South America will reach USD 500 billion and USD 250 billion respectively.

Lamenting this fact, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Josep Borrell, has stressed the need for the EU to re-engage with Latin America (20). The HR/VP has declared that ‘[i]f we want to be influential in the world, if we want to be a geopolitical power and a global actor, we cannot pretend to be so without being present in Latin America, where there is a young population and extraordinary economic potential’ (21). Furthermore, as two regions that are highly aligned on values, rights and preferences for sustainable and inclusive development, strong multilateralism, and a rules-based order, they are natural allies on the global stage.

After years of neglect, the EU’s return to the region may not be met with open arms.

In July 2023, the EU will be inviting LAC leaders to a summit in Brussels during the Spanish EU Presidency aimed at revitalising the relationship. The launch of the EU-LAC Digital Alliance in Bogotá in March 2023 was also a step in the right direction (22), as were the recent trips of high-ranking EU and Member State officials including the visit of European Commission President Ursula Von Der Leyen, European Commission Vice President Margarethe Vestager, and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz to Argentina. But after years of neglect, the EU’s return to the region may not be met with open arms, particularly if premised on the need to gain support in the context of the war in Ukraine and perceived as an attempt to bolster EU strategic autonomy.

Latin America and the Caribbean: Challenges and aspirations

The strengthening of ties with the EU is a major strategic opportunity for the LAC region. From a geopolitical point of view, this would allow it to offset its dependence on the United States and China (and in part, on Russia) without losing autonomy. Indeed, a rapprochement would enable both regions to partner in sustaining a rules-based multilateral order, with effective global governance institutions and trade exchanges free from the logic of geopolitical competition, which would in turn boost LAC’s autonomy and sovereignty.

There is also a strong economic, political and social rationale. Globally, LAC was the region most negatively affected in socio-economic terms by the Covid-19 pandemic (23), registering a 6.9% decline in GDP in its first year and a rise in poverty levels to 34% (24). It is also the second most unequal region in the world, stuck in a ‘high-inequality, low-growth trap’ (25) marked by lack of productivity, absence of foreign investment to supplement weak domestic savings, and excessive dependence on raw materials(26). Indeed, FDI inflows in 2021 represented just 9% of the global total, approximately USD 1.6 trillion in 2021. Meanwhile, over the past decade, the region’s annual growth rate has averaged just 0.9 % (27).

This performance is even worse than the region’s ‘lost decade’ of the 1980s. The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) estimates that in 2023 growth will be on average 1.3 % across the region, and warns that these poor rates of growth will do little to help job creation, nor will they allow governments to create the fiscal space they need to maintain social expenditures and transfers, invest in education, and create an environment to absorb the growing flows of migrants.’ As a result, ECLAC states that ‘the region faces the risk of experiencing episodes of social unrest alongside a rising tide of migration’ (28).

On the political level, the last electoral wave in the region gave leaders the political capital required to advance ambitious social agendas albeit with the caveat that they must contend with divided congresses. Over the past few years, elections in Colombia, Brazil, Mexico and Chile produced markedly divided congresses in a region with the fastest growing rate of political polarisation in the world over the past 20 years (29). As LAC countries harness the green and digital revolutions, it will be vital for them to ensure these processes help reduce inequalities, otherwise they risk compounding the legitimacy crisis affecting their political systems (30).

Europe could help Latin America overcome both its new and traditional challenges, assisting it in developing an economy based on trade in goods and services such as renewable energy, especially between the EU and LAC, and to lead green and digital transitions adjusted to its social agenda. The region cannot miss out on this opportunity (31).

However, relaunching the EU-LAC relationship is not without its own challenges. EU funding and investment resources and tools are limited given that many countries are ineligible for development cooperation support due to their middle-income status (an issue which seems to have lost a degree of momentum after the ‘Development in Transition’ initiatives led by the EU, OECD and ECLAC (32)). Meanwhile, European private sector investors are disincentivised by Latin America’s political and regulatory instability. As such, the region is stuck in the trap of being ‘too rich’ to attract development funds and ‘too poor’, unequal and volatile to attract the investments targeted at other regions.

The EU is attempting to find ways to resource the revitalisation of the relationship, notably through the modernisation of existing trade and association agreements (33). It is also seeking to ratify the Mercosur agreement, with negotiations stalled yet again as they approached conclusion after 20 years due to a coalition of European green parties and farmers’ associations who oppose it on environmental grounds and due to concerns over meat imports. Meanwhile, the likely impact of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) on the region’s exports to the EU is a looming concern for LAC, as it could reverse the trade gains of Mercosur and other trade and association agreements (34).

The EU’s Global Gateway programme is a potentially significant initiative for the region (35), currently financing projects in five areas: digital, climate and energy, transport, health, and education and research (36). Projects such as the extension of the BELLA submarine cable, whose aim is to connect higher education institutions across both regions, or the Copernicus satellite system, targeted at providing data to combat deforestation and other environmental threats, are currently being funded by the programme. A further €10 billion in funding was announced in the context of European Commission President

Ursula Von Der Leyen’s trip to Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Mexico in June 2023 (37). However, the complete Global Gateway Investment Agenda for Latin America and the Caribbean has yet to be finalised. In theory, it will be presented to the EU-CELAC Summit scheduled to take place in Brussels in July this year (38). Meanwhile, China is already investing heavily in the green and digital sectors of the region’s economy (39).

The EU’s Global Gateway programme is a potentially significant initiative for the region.

Thus far, we know that the EU’s Latin America and the Caribbean Investment Agenda will seek to identify ‘fair green and digital investment opportunities in Latin America and the Caribbean, which will benefit from the open environment generated by trade and investment agreements and will help achieve the Sustainable Development Goals’ (40). The agenda, which should be a key deliverable of the EU-CELAC summit, will ‘leverage quality investments to deliver on renewable energy and green hydrogen, critical raw materials, decarbonisation, and transport infrastructure projects, 5G and last-kilometre connectivity, digitalisation for public services, sustainable forest management, health products manufacturing, education and skills and sustainable finance, with a positive and values-based investment offer, respecting high international standards’ (41).

How to move ahead?

If the EU and the LAC region are to develop a strategic partnership, they should deepen their political, economic and social cooperation.

In the political realm

Despite sharing values and objectives, Latin America’s diversity and the EU’s uneven footprint there make it difficult, if not impossible, to achieve an ambitious bi-regional strategic partnership. This does not mean that the EU should pursue a differentiated approach as a matter of principle but that it should offer the region a large umbrella under which many different conversations can take place.

First and foremost, it is key for both sides to engage in an honest conversation on their willingness to translate promises into concrete results. Is the EU open to investing the political capital required so that projects such as Mercosur and the deepening of existing trade liberalisation agreements with LAC can materialise? Will the EU increase its dwindling cooperation budget for the region, advocate for LAC in multilateral forums, and adequately resource initiatives like the Global Gateway and the Digital Alliance? Will Latin America and the Caribbean create an enabling environment for EU public and private investments?

The EU must not be the reason the EU-Mercosur agreement fails.

Another key conversation must focus on how to sustain the rules-based multilateral order and how to strengthen the role of the LAC region and its states in international forums and institutions. While the region overwhelmingly condemned the Russian invasion of Ukraine (42), it has also clearly articulated its opposition towards a global economy in which geopolitics and sanctions limit its growth opportunities. Countries in the region do not want to be pushed to take sides with blocs but rather prefer to examine each topic on its own merits and then decide which position to second and who to side with, an approach referred to as ‘active non-alignment’ (43). It is a legitimate demand that should be heard and engaged with, particularly given that many countries in the region are suffering the consequences of the war, whether through Russian cyberattacks or inflationary pressures stemming from shortages of fertilisers, grain and other vital commodities.

The EU must avoid its bid for strategic autonomy being perceived as a zero-sum game aimed at guaranteeing its sovereignty and increasing its international power at the expense of others. To this end, it will have to approach strategic autonomy as a shared agenda with the region in which the decision-making capacity of its partner is also valued as a means and as an ultimate end of the relationship.

In the economic realm

LAC economies, still recovering from the pandemic, are now suffering due to the war in Ukraine and the sanctions imposed on Russia, and are moreover exposed to high energy and food prices, as well as rising inflation and interest rates (44). Accordingly, the EU’s strategy to relaunch the relationship will be evaluated according to its capacity to promote trade, investment and jobs. Even if the era of the great bi-regional trade liberalisation agreements may have passed, the EU must not be the reason the EU-Mercosur agreement fails, should this happen (45).And particularly if it fails, it will be necessary to redouble efforts to modernise existing agreements and, above all, to generate investment and trade promotion programmes, both inter- and intra-regional.

However, it is by no means guaranteed that the EU will successfully compete against China and the United States, not least given that both countries have the instruments and strategic planning capacity the EU lacks. While Chinese investments are no doubt attractive, they deepen the region’s dependence on China and incentivise the reprimarisation of its economies at the cost of manufacturing and exporting goods and services, therefore undermining their autonomy. To differentiate itself from China and the United States, the EU should orient investments instead towards supporting the region’s sustainable development through a reindustrialisation programme including high-value services and exports and a commitment to equity goals.

Regulatory quality and legal certainty are necessary conditions for this. As noted by the OECD, whose Indicators for Regulatory Policy Governance (iREG) have mapped in detail the (poor) quality of regulation in the region, this is a key factor curtailing the region’s attractiveness for private investment (46). The EU, which has introduced a wealth of initiatives to regulate the digital economy, including the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and more recently, the Digital Market and Digital Services Act, could help modernise regulatory frameworks. These regulations, which aim to promote fair competition, provide legal clarity for digital assets, and protect the privacy rights of citizens, are already impacting the region and should consequently be further explored by both parties.

While EU programmes, budgets and guarantees are key, the heavy lifting will have to be done by the private sector. For this reason, the July 2023 EU-CELAC summit should approve an investment plan that both identifies priority sectors of common interest and mechanisms for the establishment and financing of these public-private partnerships.

In the social realm

As the recently approved Ibero-American Charter of Principles and Rights in Digital Environments shows, common value agendas – while are not enough alone – do provide a platform and incentives to collaborate (47). The EU’s commitment to human rights, democracy and social values across all areas of its external action should help the societies of the region to find in the EU support for their efforts to bolster human rights protection and good governance in their own countries, promote the return to democracy where appropriate, such as in Venezuela and Nicaragua, and reverse processes of democratic deinstitutionalisation such as those observed in Central America (48).

Also, the EU can play a key role in boosting human capital in Latin America through training and education as a complement to investment packages, helping to ensure the sustainability of productive processes and to reduce inequality.

Finally, the attractiveness and sustainability of investment is linked not only to the regulatory framework for business but also to legitimate civil society concerns related to corruption, authoritarianism, government ineffectiveness and, in general, social inclusion. Supporting and engaging with civil society in LAC with a view to promoting government accountability and transparency is a key EU priority for the region (49). Civil society actors must be a central part of this strategic partnership process because it is they who will ultimately demand transformation processes that combine economic progress with values.

Conclusion

The current context of significant global change presents an opportunity for the EU and LAC to revitalise a relationship that has long punched below its weight. Yet both parties will need to seriously commit and make hard choices for this to yield fruit. On the one hand, the EU and its Member States must endeavour to successfully conclude Mercosur negotiations and to expand and modernise the network of existing trade and association agreements. They should also increase the budgetary resources available for LAC, both at the EU and national level, and help develop an investment plan drawing upon private and public resources to deliver on the promises and expectations generated by the Global Gateway.

Civil society actors must be a central part of this strategic partnership process.

It is legitimate for the EU to seek the region’s support in its quest to support the rules-based order against the challenges posed by Russia and China, as well as to help support its own green and digital transitions and economic growth. However, the EU cannot be perceived as exclusively interested in exploiting LAC natural resources and markets to secure its own strategic autonomy, and rallying the region’s UN votes while simultaneously digital transitions and economic growth. However, the EU cannot be perceived as exclusively interested in exploiting LAC natural resources and markets to secure its own strategic autonomy, and rallying the region’s UN votes while simultaneously ignoring the region’s needs and preoccupations. LAC does not need more extractivism, whether of its raw materials or data, but true partners in developing local industries and services that promote growth and social inclusion. On the other hand, LAC countries must seriously engage in deep regulatory and institutional reform to attract foreign investments and capital. Therefore, in cooperating on socially inclusive green and digital transitions, the EU and LAC could establish a more sustainable, long-term, human rights-centred partnership, enabling both to address shared challenges and goals.

References

European Commission, ‘New Agenda to strengthen EU’s partnership with Latin America and the Caribbean’, op.cit.

1.Latin America and the Caribbean comprises 33 countries spanning South America, Central America, Mexico, and the Caribbean.

2. For an analysis of how global interdependencies are being weaponised by great power competition, see Leonard, M. (ed.), The Power Atlas: Seven battlegrounds of a networked economy, ECFR, 2021 (https://ecfr.eu/wp- content/uploads/power-atlas.pdf) and Leonard, M. (ed.), Connectivity Wars: How migration, trade and finance are the geo-economic battlegrounds of the future, ECFR, 2016 (https://ecfr.eu/archive/page/-/Connectivity_Wars.pdf).

3. See: Ahn, J., Habib, A., Malacrino, D., and Presbitero, A., ‘Fragmenting foreign direct investment hits emerging economies hardest’, IMF Blog, 5 April 2023 (https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2023/04/05/ fragmenting-foreign-direct-investment-hits-emerging-economies- hardest).

4. Freedom House, ‘Marking 50 years in the struggle for democracy’, Freedom in the World, 2023 (https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom- world/2023/marking-50-years).

5. Granés, C., ‘La maldición latinoamericana’, Política Exterior, Vol. XXXVI, No 210, 2023, pp. 60-79.

6. For a discussion on European sovereignty, see Leonard, M. and Shapiro J., “Empowering EU Member States with strategic sovereignty”, ECFR Policy Brief, June 2019 (https://ecfr.eu/wp-content/uploads/1_ Empowering_EU_member_states_with_strategic_sovereignty.pdf).

7. For the full definition of EU ‘strategic autonomy’, see European Parliament, ‘EU strategic autonomy 2013-2023: From concept to capacity’, July 2022 (https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/ document/EPRS_BRI(2022)733589).

8. Policy statement by Olaf Scholz, Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany and Member of the German Bundestag, 27 February 2022 (https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-en/news/policy-statement- by-olaf-scholz-chancellor-of-the-federal-republic-of-germany- and-member-of-the-german-bundestag-27-february-2022-in- berlin-2008378).

9. See Dennison, S. and Zerka, P., ‘Tracking Europe’s energy security: Four lessons from the EU’s new energy deals’, ECFR Commentary, 24 November 2022 (https://ecfr.eu/article/tracking-europes-energy- security-four-lessons-from-the-eus-new-energy-deals/).

10. The global renewable energy transition will require the mass deployment of battery storage technologies, with lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries expected to play an important role. Currently, Chinese companies control most of the world’s Li-ion supply chain. However, according to a report by environmental campaign group Transport & Environment, the EU is on track to produce enough lithium-ion battery cells to meet demand and cut China from supply chains by 2027. However, this risks being derailed by US subsidies to battery manufacturing via the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) which could prompt European companies to relocate. According to the report, more than two-thirds (68 %) of lithium-ion battery production planned for Europe is at risk of being delayed, scaled down or cancelled. See Transport & Energy, ‘Two-thirds of European battery production at risk – analysis’, March 2023 (https://www. transportenvironment.org/discover/two-thirds-of-european-battery- production-at-risk-analysis/)

11. Today, nearly 80 % of suppliers to European firms operating in the semiconductor industry are located outside the EU. The EU’s share in global production capacity is below 10 %. It was in this context that the Chips Act was formulated which seeks to secure the EU’s supply of semiconductors by boosting domestic production in a context of global shortage. See European Parliament, ‘Chips Act – the EU’s plan to overcome semiconductor shortage’, February 2023 (https://www. europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20230210STO74502/ chips-act-the-eu-s-plan-to-overcome-semiconductor-shortage).

12. It is estimated that by 2030, the EU will need up to 18 times more lithium and five times more cobalt just for energy storage and e-car batteries alone. See European Commission, ‘Commission announces actions to make Europe’s raw materials supply more secure and sustainable’, 3 September 2020 (https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/ en/ip_20_1542). See Euronews, ‘Europe in race to secure raw materials critical for energy transition’, 8 March 2023 (https://www.euronews. com/next/2023/03/07/europe-in-race-to-secure-raw-materials-critical-for-energy-transition).

13. The region holds more than half of global lithium reserves, produces 40 % of the world’s copper, and has significant potential in graphite and other rare earth elements. See Bernal, A. et al. ‘Latin America’s opportunity in critical minerals for the clean energy transition’, IEA (https://www.iea.org/commentaries/latin-america-s-opportunity-in- critical-minerals-for-the-clean-energy-transition).

14. In January 2023, after having cancelled a contract with a German firm, the Bolivian government chose a Chinese consortium to help develop the world’s largest reserves of lithium, located in its iconic salt flats.Former Bolivian President Evo Morales praised the agreement saying the Chinese offer entailed ‘no conditions’. See ‘Bolivia taps Chinee battery giant CATL to help develop lithium riches’, Reuters, 20 January 2023 (https://www.reuters.com/technology/bolivia-taps-chinese-battery- giant-catl-help-develop-lithium-riches-2023-01-20). Also see Adler, A. and Ryan, H., ‘An opportunity to address China’s growing influence over Latin America’s mineral resources’, Lawfare, 8 June 2022 (https://www. lawfareblog.com/opportunity-address-chinas-growing-influence-over- latin-americas-mineral-resources).

15. The authors have dealt with this topic more extensively in Hobbs, C., and Torreblanca, J.I., ‘Byting back: The EU’s digital alliance with Latin America and the Caribbean’, ECFR Policy Brief, October 2022 (https:// ecfr.eu/publication/byting-back-the-eus-digital-alliance-with-latin- america-and-the-caribbean/).

16. The HRVP, Josep Borrell, admitted that the ‘we have not had the relationship with Latin America that we should have had’, attributing this to ‘greater urgencies that have come to Europe from other fronts’. See Borrell, J., ‘Why Europe and Latin America need each other’, EEAS, 30 November 2022 (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/why-europe-and- latin-america-need-each-other_en).

17. Jung Altrogge, T., ‘A new cycle in Euro-Latin American cooperation: shared values and interests’, Documentos de Trabajo, Fundación Carolina, 37/EN 2021 (https://www.fundacioncarolina.es/wp-content/ uploads/2021/05/DT_FC_47_en.pdf).

18. In the Declaration of Río de Janeiro signed after the First Summit between the Heads of State and Government of Latin America and the Caribbean and the European Union held in Rio in June 1999, both parties committed themselves to ‘to strengthen the links of political, economic and cultural understanding between the two regions in order to develop a strategic partnership’, EU-LAC Summit Declaration, Río de Janeiro,28-28 June 1999. (https://intranet.eulacfoundation.org/en/system/ files/1999_EN_Rio_Decl.pdf).

19. See ‘Byting back: The EU’s digital alliance with Latin America and the Caribbean’, op.cit.

20. In this context, on 7 June 2023, the High Representative and European Commission adopted a ‘New Agenda for Relations between the EU and Latin America and the Caribbean’, which seeks to ‘recalibrate and renew bi-regional relations’. It makes a series of proposals in the following areas: ‘A renewed political partnership; strengthening common trade agenda; rolling out Global Gateway investment strategy to accelerate a fair green and digital transition and tackle inequalities; joining forces for justice, citizen security and the fight against transnational organised crime; working together to promote peace and security, democracy,rule of law, human rights and humanitarian aid; and building a vibrant people-to-people partnership’. See: European Commission, ‘New Agenda to strengthen EU’s partnership with Latin America and the Caribbean’, Press release, 8 June 2023 (https://ec.europa.eu/commission/ presscorner/detail/en/IP_23_3045).

21. Borrell, J., ‘Borrell visits Latin America: high time to re-engage’, EEAS, 7 November 2021 (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/borrell-visits-latin- america-high-time-re-engage_en).

22. The EU-LAC Digital Alliance was launched in Bogotá on 14 March. See: European Commission, ‘Global Gateway: EU, Latin America and Caribbean partners launch in Colombia the EU-LAC Digital Alliance’, Press release, 16 March 2023 (https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/ en/news/global-gateway-eu-latin-america-and-caribbean-partners- launch-colombia-eu-lac-digital-alliance).

23. Pan American Health Organization, ‘The prolongation of the health crisis and its impact on health, the economy and social development’, ECLAC 2021 (https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/54991); Gaviria, A. and Ramos, G., ‘Regional coordination for strengthening pandemic preparedness, vaccine access, and effective implementation of vaccine deployment plans’, The Lancet COVID-19 Commission Regional Task Force for Latin America and the Caribbean, November 2021 (https:// static1.squarespace.com/static/5ef3652ab722df11fcb2ba5d/t/61d317cfc928 c1690363cb9d/1641224144514/LAC+Final+Dec+2021.pdf).

24. CEPALSTAT, ‘Main figures of Latin America and the Caribbean’, ECLAC, 2022 (https://statistics.cepal.org/portal/cepalstat/index.html?lang=en).

25. UNDP, Trapped? Inequality and Economic Growth in Latin America and the Caribbean, Regional Human Development Report 2021 (https://www. undp.org/latin-america/publications/trapped-inequality-and-economic- growth-latin-america-and-caribbean).

26. See Melguizo, A. and Muñoz, V., ‘Tiempo para valientes: América Latina vista desde D.C.’, Crónica, 24 April 2023.

27. See Salazar-Xirinachs, J. M., ‘How Latin American and Caribbean countries can mitigate slow growth in 2023’, CEPAL, 29 March 2023 (https://www.cepal.org/en/articles/2023-how-latin-american-and- caribbean-countries-can-mitigate-slow-growth-2023).

28. While foreign direct investment to Latin America and the Caribbean did increase in 2021 after significantly decreasing the previous year due to the outbreak of Covid-19, it did not return to pre-pandemic levels. See CEPAL, ‘Foreign Direct Investment in Latin America and the Caribbean 2022’, 2022 (https://www.cepal.org/en/publications/48521-foreign- direct-investment-latin-america-and-caribbean-2022).

29. See UNDP, ‘“Conmigo o en mi contra”: La intensificación de la polarización política en América Latina y el Caribe’, March 2023 (https:// www.undp.org/es/latin-america/blog/conmigo-o-en-mi-contra-la- intensificacion-de-la-polarizacion-politica-en-america-latina-y-el- caribe).

30. O’Neil, S., ‘Perder y ganar con la globalización’, Política Exterior, Vol. XXXVI, No 210, 2023 pp. 50-59.

31. Ploger, I., ‘The reindustrialization of Latin America: Are we going to lose this opportunity again?’, Latin Trade, 26 May 2021 (https://latintrade. com/2021/05/26/the-reindustrialization-of-latin-america-are-we- going-to-lose-this-opportunity-again).

32. OECD, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, CAF Development Bank of Latin America and European Union, Latin American Economic Outlook 2019: Development in transition, 2019 (https://repositorio. cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/44515/4/S1900181_en.pdf).

33. The goal the HR/VP, Josep Borrell, has set is to modernise the existing association agreements with Mexico and Chile, sign the negotiated post- Cotonou agreement with the African, Caribbean and Pacific community, ratify the association agreement with Central American countries, and finalise the EU-Mercosur agreement. See: Borrel, J., ‘Why Europe and Latin America need each other’, op.cit.

34. According to a report by the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture (IICA), the CBAM could have significant impacts on agricultural and food trade in Latin America and the Caribbean. It could increase production costs for exporters and make their products less competitive in the EU market, potentially leading to a decline in exports and income for Latin American farmers and producers . See: Green Initiative, ‘Latin American food exporters worried about impacts of EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism on agricultural and food trade’, 15 March 2023 (https://greeninitiative.eco/2023/03/15/the-potential- impact-of-eus-carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism-on-latin- american-food-producers-mitigation-actions-and-support-from- green-initiative/).

35. On how the EU can best leverage Global Gateway in LAC, see: Melguizo, Á. and Torreblanca, J.I., ‘Digital diplomacy: How to unlock the Global Gateway’s potential in Latin America and the Caribbean’, ECFR, 22 May 2023 (https://ecfr.eu/article/digital-diplomacy-how-to-unlock-the- global-gateways-potential-in-latin-america-and-the-caribbean/).

36. For a list of the projects under way, see: European Commission, Global Gateway, ‘EU-Latin America and the Caribbean flagship projects for 2023’, March 2023 (https://international-partnerships.ec.europa. eu/system/files/2023-05/EU-LAC-flagship-projects-for-2023-v05. pdf).

37. See European Commission, ‘In Brazil, President von der Leyen announces EUR 10 billion of Global Gateway investments in Latin America and the Caribbean’, 13 June 2023, (https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and- policy/priorities-2019-2024/stronger-europe-world/global-gateway/ global-gateway-latin-america-and-caribbean_en).

38. For a comprehensive review and critique of Global Gateway and its deployment and governance problems, see Buhigas Schubert, C. and Costa, O., ‘Global Gateway: Strategic governance & implementation’, European Parliament Policy Department for External Relations, June 2023 (https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ STUD/2023/702585/ EXPO_STU(2023)702585_EN.pdf).

39. Albright, Z., ‘Latin America and the Caribbean’s relationship with China rebounds with pivot toward green energy, electric vehicle supply chains’, Boston University Global Development Center Blog, 23 April 2023 (https://www.bu.edu/gdp/2023/04/23/latin-america-and-the- caribbeans-relationship-with-china-rebounds-with-pivot-toward- green-energy-electric-vehicle-supply-chains/).

40. European Commission, ‘New Agenda to strengthen EU’s partnership with Latin America and the Caribbean’, op.cit.

41. European External Action Service, ‘A new agenda for relations between the EU and Latin America and the Caribbean’, Factsheet, June 2023 (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/2023/ Factsheet_JC_EU-LAC.pdf).

42. All countries in Latin America and the Caribbean supported the UN General Assembly resolution in March 2022 against Russia’s actions in Ukraine apart from Bolivia, Cuba, El Salvador, and Nicaragua who abstained. Venezuela’s vote is not deemed valid given its debts to the organisation. The resolution was adopted by 141 in favour, 5 against and 35 abstentions. See: EEAS, ‘UN General Assembly demands Russian Federation withdraw all military forces from the territory of Ukraine’, 2 March 20022 (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/un-general- assemblydemands-russian-federation-withdraw-all-military-forces- territoryukraine_en).

43. The recent controversial declarations of Brazilian President, Luiz Ignacio Lula da Silva, and Colombian President, Gustavo Petro, on the Ukraine war are a good case in point. See: AP News, ‘Brazil’s Lula in Portugal amid Ukraine remarks controversy’. See also: Fortín, C., Heine, J., and Ominami, C., ‘La renovada vigencia del No Alineamiento Activo’, Política Exterior Vol. XXXVI, No 210, 2023 pp. 70-82. The Economist has described the region’s views on the international order as ‘transactional’. The Economist, ‘How to survive a superpower split’, 11 April 2023 (https:// www.economist.com/international/2023/04/11/how-to-survive-a- superpower-split).

44. Adler, G., Chalk, N. and Ivanova, A., ‘Latin America faces slowing growth and high inflation amid social tensions’, IMF Blog, 1 February 2023 (https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2023/02/01/latin-america-faces-slowing-growth-and-high-inflation-amid-social-tensions).

45. After 20 years of negotiations, the EU and the Mercosur reached an agreement in 2019. However, the deal has not been ratified due to environmental concerns of, mostly, the German and French governments. See: Stender, F., ‘Sitting, waiting, wishing: Why the EU- Mercosur remains on hold’, LSE Blog, 11 October 2002 (https://blogs.lse. ac.uk/europpblog/2022/10/11/sitting-waiting-wishing-why-the-eu- mercosur-agreement-remains-on-hold/).

46. See OECD, ‘OECD indicators of regulatory policy and governance (iREG) for Latin America 2019’, in Government at a Glance: Latin America and the Caribbean 2020, OECD.

47. See XXVIII Ibero-American Summit of Heads of State and Government, ‘Together towards a just and sustainable Ibero-America’, Ibero- American Charter of Principles and Rights in Digital Environments,25 March 2023 (https://www.segib.org/wp-content/uploads/Carta_ iberoamericana_derechos_digitales_ESP_web.pdf).

48. Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán have pointed at three factors which explain the pattern of democratic stagnation in Latin America: one, ‘powerful actors that block democratic deepening’; two, ‘poor governing results that fuel dissatisfaction and pave the way for authoritarian populists’; and third, ‘hybrid states that violate citizens’ rights, fail to provide security and quality public services, and are captured by powerful interests’. Mainwaring, S. and Pérez-Liñán, A., ‘Why Latin America’s democracies are stuck’, Journal of Democracy, Vol. 34, No 1, January 2023,pp. 156-170.

49. European External Action Service, ‘Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council: European Union, Latin America and the Caribbean: joining forces for a common future’, 16 April 2019 (https:// eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A52019JC0006).